- within International Law topic(s)

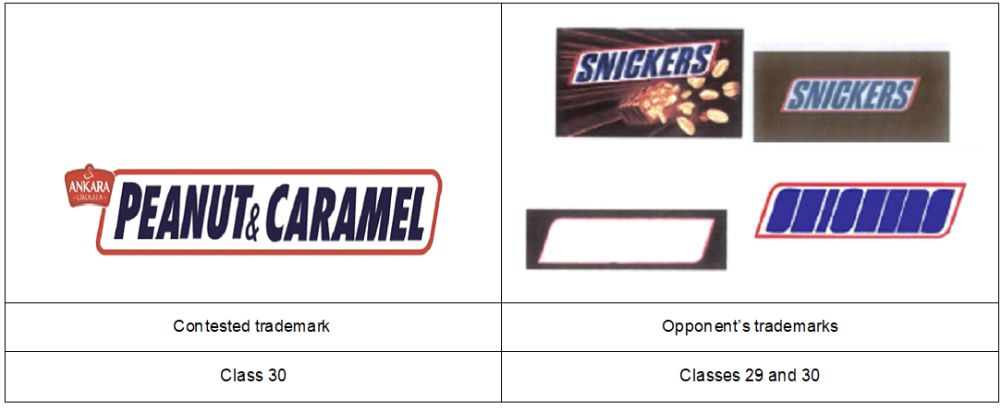

- The IP Court found that there was a likelihood of confusion between a figurative mark containing the words 'Ankara çikolata peanut & caramel' and earlier SNICKERS marks

- The Regional Court of Appeals agreed, and the Court of Cassation dismissed the appeal

- The well-known status of the opponent's marks in the food sector enhanced the likelihood of confusion between the marks

A recent IP Court decision has highlighted the impact of conceptual similarity and well-known status on the likelihood of confusion analysis.

Background

The opponent challenged the contested trademark at the administrative stage before the Turkish IP Office ('the office') on the basis of a likelihood of confusion, the well-known status of its marks in Türkiye and in countries party to the Paris Convention, and bad-faith filing.

After the opponent's claims were dismissed by the office, the opponent proceeded with a court action before the IP Court of Ankarare questing the cancellation of the office's decision, as well as the invalidation of the contested trademark in its entirety.

IP Court decision

The IP Court, after examining the merits of the case, concluded that the contested mark and the opponent's trademarks coveredidentical goods, and that the contested sign was confusingly similar to the opponent's earlier marks. The IP Court also noted thatthe well-known status of the opponent's trademarks in the food sector enhanced the likelihood of confusion between the parties'marks. However, while it allowed the opponent's claims on the basis of a likelihood of confusion and the well-known status of the earlier marks, the IP Court refused the allegations of bad faith, stating that there was no hard evidence that the contestedtrademark had been filed in bad faith.

Appeal decisions

Upon the office's appeal, the case was examined by the Regional Court of Appeals. The court found as follows:

Although there was no similarity between the word elements of the parties' marks, namely 'Snickers' and 'Ankara çikolata peanut & caramel', the composition of the opponent's trademarks was copied in the contested mark.

The dark blue italic font in the contested sign was specific to, or identified with, the opponent.

The word elements 'peanut' and 'caramel' in the contested mark defined the images of peanut and caramel displayed in the opponent's trademarks.

The reputation of the opponent's trademarks enhanced the likelihood of confusion between the marks.

Although the office proceeded with another round of appeal before the Court of Cassation, the latter sustained the lower courts'rulings and the judgment became final.

Comment

This decision, which was also upheld by the Court of Cassation, is a reminder of the importance of conceptual similarity in theoverall comparison of conflicting trademarks. Although the Court of Cassation did not specifically mention this in its decision, it isbelieved that the existence of the opponent's trademarks below played a significant role, since the red parallelogram registered as afigurative mark in the name of the opponent is entirely copied in the contested sign:

In addition, the blurred typeface in Figure 2 provides the opponent with more comprehensive protection, especially in cases where the word mark SNICKERS is not copied. However, here the owner of the contested mark went one step further and used the words'peanut' and 'caramel', in addition to copying the red parallelogram and typeface of the opponent's mark, which would lead consumers to believe that the contested mark belonged to, or was somehow associated with, the opponent. Nevertheless, the fact that none of the courts admitted that the contested trademark was filed in bad faith is quite controversial.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]