- within International Law topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Media & Information, Oil & Gas and Property industries

- within Environment topic(s)

During President Trump's recent trip to Asia, the United States signed "Frameworks" with Japan and Australia, as well as Memoranda of Understanding with Malaysia and Thailand. Among the various goals of these four agreements is securing the U.S. supply of critical minerals and rare earths. Since then, the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) has finalized its 2025 list of critical mineral commodities, expanding coverage to 60 mineral commodities. The agreements and the USGS' broadening conception of which commodities are "critical minerals" underscore U.S. efforts to diversify and secure U.S. supply chains for critical minerals and rare earths away from China, which controls around 70% of rare earth processing globally, notwithstanding the recent U.S.-China détente. Interested parties may have opportunities to engage in the implementation of these agreements.

Further Expansion of "Critical Minerals"

In August, USGS published a list of 54 mineral commodities proposed for inclusion on the 2025 list of critical minerals, part of a regular review. Administratively, the critical minerals list guides strategies to secure U.S. mineral supply chains and has direct implications for trade initiatives, including the ongoing Section 232 investigation of processed critical minerals.

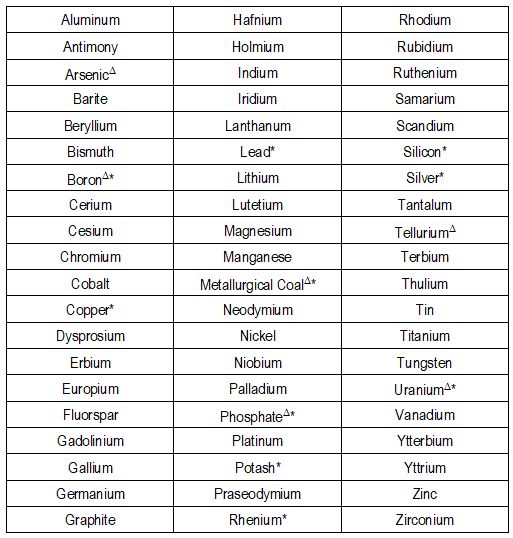

This final list that USGS published November 7 follows a public comment period that concluded in September. The 60 mineral commodities on the final list are as follows. Mineral commodities added to the list since its 2022 iteration are marked with an asterisk (*). Mineral commodities included on the final 2025 list, but absent from the proposed 2025 list that was subject to public comment are marked with a delta (∆):

Comparing the proposed and final 2025 lists, three things are noteworthy. First, the final list walks back the proposal to remove arsenic and tellurium, which had appeared on all prior editions of the critical minerals list. Removal of these two mineral commodities was opposed by the Department of Defense. Second, the final list maintains the six originally proposed mineral commodity additions: copper, lead, potash, rhenium, silicon, and silver. Third, it adds four more mineral commodities that were absent from the 2025 proposed list: boron, phosphate, metallurgical coal, and uranium. USGS had specifically requested comments on whether to include metallurgical coal and uranium in its 2025 proposal. Notably, although some minerals like phosphate were not included in the proposed list based upon a study by the U.S. Geological Survey, the final list does not revisit that study. Instead, it states that the elements were added at the request of other agencies.

Since the 2022 edition, the list of critical minerals has been maintained pursuant to Section 7002 of The Energy Act of 2020. In general, Section 7002(a)(3) defines "critical mineral" as substances "designated as critical by the Secretary under subsection (c)," but specifically excludes "fuel minerals," among other substances. In adding metallurgical coal and uranium to the final 2025 list, USGS states that the inclusion was recommended by the U.S. Department of Energy and relies on Section 7002(c)(4)(B), which permits the inclusion of "any mineral, element, substance, or material determined by another Federal agency to be strategic and critical to the defense or national security of the United States." It appears that the Administration views the breadth of Section 7002(c)(4)(B) to permit inclusion of fuel minerals on the list, notwithstanding the general definitional restrictions of Section 7002(a)(3)(B)(i).

Trade Implications: Section 232 and Dealmaking

While the USGS list of critical minerals is not, by itself, a trade measure, it nevertheless informs and influences U.S. trade policy in several ways. First, the ongoing investigation of processed critical minerals pursuant to Section 232 of the Trade Expansion Act of 1962 (Section 232) defines "critical minerals" for purposes of that investigation by reference to the critical minerals list published by USGS, "or any subsequent such list," in addition to separately and specifically including uranium. Thus, an expansion (or contraction) of the USGS list would likewise impact the potential scope of any Section 232 action.

Second, the U.S. Government has been actively pursuing engagement with allies and like-minded countries to secure critical minerals supply chains through initiatives like the Minerals Security Partnership and the promotion of seabed mining. Recent trade dealmaking has referenced critical minerals cooperation as an intended outcome, including the recent bilateral Frameworks and Memoranda of Understanding with Japan, Malaysia, Thailand, and Australia.

Third, there are several provisions in U.S. law that are applicable specifically to transactions involving critical minerals. These include rules involving Foreign Entities of Concern and tax benefits for EV batteries. Products included on the final list could now be subject to increased scrutiny under these provisions.

Terms of the Critical Minerals Deals

In general, the agreements can be separated into two groups. The "Frameworks" established with Japan and Australia, respectively, are each similarly structured, more concrete, and more ambitious. Likewise, the Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) signed by Malaysia and Thailand, respectively, are each similarly structured, but are more limited in scope. However, the U.S.-Malaysia MOU is also complemented by several provisions intended to develop and align Malaysia's critical mineral sector in the U.S.-Malaysia Agreement.

U.S.-Australia and U.S.-Japan Framework Commitments

In the U.S.-Australia and U.S.-Japan Frameworks, the countries agreed to accelerate the process of securing supplies of critical minerals and rare earths, including through government and private sector support. The countries will jointly select projects of interest to address gaps in critical mineral and rare earth supply chains. The U.S.-Japan Framework also covers derivative products.

Within six months, the U.S., Japan, and Australia will also provide financial support for selected projects in these countries (and potentially other "like-minded countries" under the Framework with Japan). The United States and Australia specifically agree to provide at least $1 billion within that timeframe to finance projects expected to generate end products for delivery to buyers. Also within six months, the parties are to convene a Mining, Minerals and Metals Investment Ministerial to promote investment in mining. The U.S.-Japan Framework specifically intends the Ministerial to be a "dialogue with relevant stakeholders."

Furthermore, these Frameworks establish a rapid response mechanism, under the leadership of the U.S. Secretary of Energy and equivalent authorities from Japan and Australia, respectively, to identify priority minerals and supply vulnerabilities, among others. The Frameworks also express the countries' commitment to investing in minerals recycling technologies and to ensure management of critical minerals and rare earth scrap to support supply chain diversification. The countries will also assist in mapping mineral resources within their lands, and potentially elsewhere, to support diversified critical minerals supply chains. The countries will work together with third parties as appropriate to ensure supply chain security.

Malaysia and Thailand MOU Commitments

The MOUs with Malaysia and Thailand each include a provision that, in practice, appears to give priority to U.S. investors in critical minerals assets that may be sold in Thailand/Malaysia or by a company headquartered or incorporated in Thailand/Malaysia. The MOU with Thailand specifies that the investment projects will include provisions for technology transfer, capacity building, and training of domestic personnel and that cooperation should prioritize development of domestic processing industries and value chains in Thailand. The MOU with Thailand also states that the countries intend to provide information to each other regarding potential tenders and projects at the earliest practicable moment, and in any case no later than such information is provided to other potential investors, so as to enable the countries to disseminate this information to their companies and partners with sufficient time for the recipients to participate in such tenders and projects. These provisions are likely designed to benefit the U.S. investors interested in critical minerals supply chain in Thailand and Malaysia.

Common Commitments and Opportunity for Engagement

All four agreements state that the countries will work to secure their critical minerals and rare earths supply chains from non-market policies and unfair trade practices and protect responsible market participants through price floors or similar measures. They also state that the countries will work together to review and deter critical minerals and rare earths asset sales on national security grounds. Both provisions are likely aimed at countering China. The agreements also seek to streamline the permitting processes for critical minerals and rare earths mining, separation, and processing and improve other relevant regulatory practices. The agreement with Japan is unique in that the countries intend to work together to consider a mutually complementary stockpiling arrangement.

While the agreements are general in nature, there could be future opportunities for private sector engagement. The MOU with Thailand lists "meetings and information exchanges with the private sector, universities, and other stakeholders" as a mechanism for cooperation between the countries, with the MOU with Malaysia including a provision to the same effect. The agreement with Japan states that the countries will promote dialogue amongst upstream and downstream companies to facilitate the diversification of supply chains. It is unclear if and how trade measures will be used to secure the supply chains, with only the agreement with Japan stating that the countries will leverage "trade measures where appropriate." More details may come as each agreement includes a provision about the countries meeting in the future to engage in further discussions.

Optimizing Supply Chains

Cassidy Levy Kent's attorneys, economists, compliance experts, and licensed customs brokers help companies sort through the latest changes with respect to trade and tariffs and develop strategic responses. Cassidy Levy Kent has extensive experience preparing comments for and engagement with U.S. government agencies and in counseling clients to plan compliant supply chains that manage tariff risks. Our team's deep familiarity with trade law and policy enables clients to adapt and stay ahead of the curve.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.