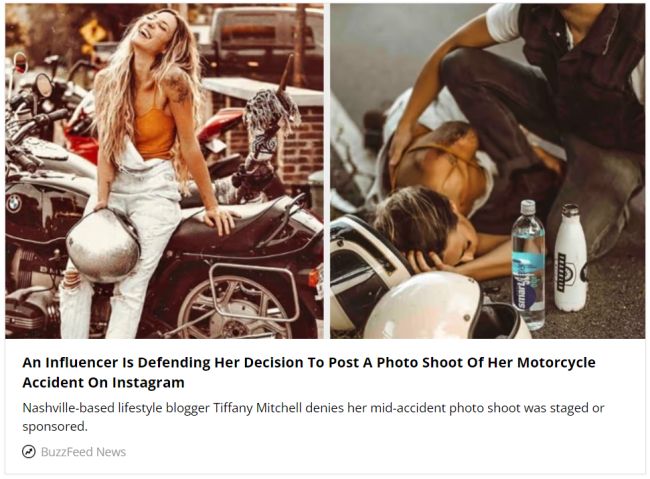

Tiffany Mitchell (@tifforeli), an influencer who currently has just under 200,000 followers on Instagram, likes to ride a beemer. Mitchell's friend Lindsey Grace Whiddon (the plaintiff) is a professional photographer. On a summer day in 2019, Whiddon took a photo of Mitchell leaning against her motorcycle, wearing faded denim overalls (torn perfectly at the knee) and a saffron colored tank top. Mitchell looks fresh and super cute. (You can see the photo here.) Later that same day, Mitchell (in her own words) "misjudged a curve" and crashed her bike. At the scene of the accident, Whiddon continued to take pictures while another friend (a handsome dude with perfect hair - beautiful people flock together) tended to Mitchell by the roadside. Mitchell was banged up and shaken by her experience but, fortunately, not seriously injured. Naturally, Mitchell posted about the experience a few days later on Instagram. Her post included the pre-accident glamour shot, several post-accident photos, and a long-ish (or Instagram) account of Mitchell's harrowing experience.

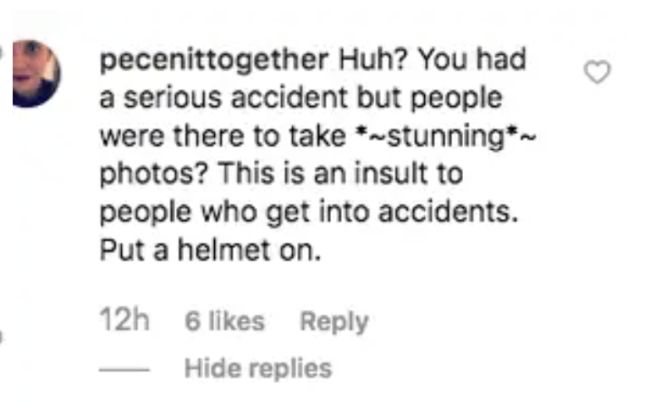

Reaction to the post was mixed. While some expressed concern for Mitchell, others found it odd that Whiddon would photograph the accident rather than attend to an injured friend. Comments like this captured the sentiment of some:

Due in part to the professional look of Whiddon's photography - and to the placement, in one of the images, of a bottle of Smartwater by Mitchell's side as she lay on the ground waiting for an ambulance - some even wondered whether the entire thing was staged. (As one snarky commentator put it: "Paid in partnership with Smartwater.") After things got a little ugly, Mitchell archived the post so it was no longer viewable.

About a month after the accident, Buzzfeed published this story:

The article reports on the reaction to Mitchell's post, includes an interview with Mitchell in which she responds to critics, and reproduces Mitchell's post in its entirety, including four of Whiddon's photos. After securing a copyright registration for the photos, Whiddon sued for copyright infringement.

Last month, Judge Colleen McMahon (SDNY) granted Buzzfeed's motion to dismiss on fair use grounds. Here's how things shook out.

1. The Purpose and Character of the Use.

Buzzfeed's use of the photographs was transformative. Whiddon took the photos, and Mitchelll published them on Instagram, "for their contents, [i.e.,] to depict Michell and her motorcycle accident." Buzzfeed used the photos for the "far different purpose" of reporting on the controversy surrounding Mitchell's social media post. Noting that other courts (see this post) have held that reporting on a controversial social media post is "a sufficiently transformative purpose to make a full reproduction of the post and its copyrighted material fair use," the court explained why using the photos, in their entirety, was "necessary and appropriate for reporting on the controversy":

"The author could not have simply reproduced the negative comments, as the comments alone would not have explained why the Instagram users felt the way they did. In one case, a user comments, "Huh? You had a serious accident but people were there to take *~stunning*~ photos? This is an insult to people who get into accidents. Put a helmet on." The reader understands why the commentator accuses Ms. Mitchell of glamorizing motorcycle accidents with the Photographs, because they can see the "stunning" Photographs and Ms. Mitchell's accompanying narrative. No other images could serve the same purpose as the screenshots in the Post."

Whiddon attempted to distinguish Buzzfeed's use of the accident photo with the Smartwater bottle (which she apparently conceded had been used fairly) from the use of the other photos, including the pre-accident photo, which Whiddon argued were used merely for illustrative purposes. The court was not persuaded:

"The Pre-Accident Photograph is the first photograph in the Post. The Defendant did not merely use the Pre-Accident Photograph as a generic image of Ms. Mitchell, just to accompany the Article. Rather, the Pre-Accident Photograph provides the reader with insight into the aesthetic choices of the earlier, staged photoshoot. The juxtaposition with the Post-Accident Photographs allows the reader to consider whether the later photographs appear to be a continuation of the photoshoot and to assess the credibility of Ms. Mitchell's comments that they were not staged."

Judge McMahon also rejected Whiddon's argument that the photos were not related to the subject matter of Buzzfeed's article, which Whiddon described as the controversy over whether Mitchell had staged the accident for a sponsored advertisement with Smartwater:

"The topic of the controversy is also not limited to the whether the Post was sponsored by Smartwater. The Article is titled "An Influencer Is Defending Her Decision To Post a Photoshoot Of Her Motorcycle Accident on Instagram." The Article's reporting on the allegations that the social media post was sponsored by Smartwater is limited to a few sentences of the whole article. The bulk of the article is devoted to remarks by Ms. Mitchell and comments by Instagram users, criticizing the Plaintiff's choice to take photographs after the accident, questioning the sensitivity of seeming to glamorize a motorcycle accident, and alleging that Ms. Mitchell staged the Post-Accident photographs. As a result, the Post-Accident Photographs are perfectly appropriate to help explain why critics are making those accusations." (Cleaned up.)

2. The Nature of the Copyrighted Work.

The second factor requires courts to evaluate how close to the "core" of intended copyright protection the work in question is, with expressive or creative works being considered closer, and factual or information works being considered further, from that core. Even though the photos documented a real-life event - one that the plaintiff strenuously argued was not staged - the court found that the photos were "expressive" and "demonstrate[d] features of creativity." The post-accident photos, for example, "showcase the emotion and drama of the motorcycle accident through manipulation of the camera focus and the capture of the accident at multiple angles." The court ruled that the the second statutory factor favored the plaintiff, "but not decidedly so" since this factor is "rarely determinative."

3. The Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used.

The third factor favored Buzzfeed, since use of the photos in their entirety was justified:

"Buzzfeed could not have displayed anything less than the entirety of the Photographs, nor edited the Screenshots to reduce the visible portions of the Photographs. Reducing the amount of the original work would have provided an incomplete description of the controversy, or even misrepresented the Post. In the context of news reporting and analogous activities ... the need to convey information to the public accurately may ... make it desirable and consonant with copyright law for a defendant to faithfully reproduce an original work without alteration. The entirety of each Photograph in the Post was necessary to provide the full context of the subject of the controversy. Accordingly, the third factor favors Buzzfeed." (Citations omitted.)

4. The Effect on the Market.

Because Buzzfeed's publication of the photos was not likely to harm any market for Whiddon's photos, the fourth factor also favored Buzzfeed.

Buzzfeed's inclusion of the screenshots of Mitchell's social posts was unlikely to interfere with the plaintiff's ability to license the photos to publications interested in photographs of women posing with motorcycles or women involved in motorcycle accidents (the most likely potential markets). Certainly, it was "highly unlikely that someone looking to license the Photographs for their contents would seek a license from the Defendant over the Plaintiff."

In addition, the court found that it "beg[ged] credulity" that Whiddon had intended to license the photos for the same purpose that Buzzfeed had used them - i.e., in articles about the controversy surrounding Mitchell's post about her accident - since doing so would subject her friend to further unwanted attention and harassment. Judge McMahon, it would seem, has a noble view of the immutability of friendships. (But see Real Housewives of Salt Lake City, Season 3, Episode 10.) Moreover, that Whiddon had allowed her macro influencer friend to share the photos on Instagram "a platform premised on freely sharing images with as many people as possible ... cuts against any suggestion that she had plans to commercialize the Photographs."

The plaintiff urged the court to follow Otto v. Hearst (see this post), a case in which an amateur photographer took a photo of then-President Donald Trump as he crashed a wedding at Trump's club in New Jersey. Without authorization, another guest at the wedding had published the photo on Instagram, and Hearst included it in a story about the incident without the photographer's permission. The court in Otto held that Hearst's use did not qualify for fair use. With respect to the fourth statutory factor, the court determined that it was not relevant that, at least initially, the plainitff had not intended to commercialize his photo, since "[c]opyright protect owners who immediately market a work no more stringently than owners who delay before entering the market." Judge McMahon distinguished Otto from the instant case:

"There are critical differences between the market effect in Otto and the market effect here. First, there is no indication within Plaintiff's Complaint that at any point she intended to license the Photographs. Plaintiff notes that there was a clear commercial licensing market because multiple media outlets would go on to publish the Photographs and accompanying stories on the controversy. However, at no point does the Plaintiff indicate that she actually attempted to enter the market or ever had any intention of entering the market. The court in Otto rightfully recognized that a copyright holder should not be denied compensation just because he failed to quickly monetize his work. But it did not suggest that a plaintiff can shake down a news organization for a licensing payment for a copyrighted work that she never intended to license." (Citations omitted.)

The very short shelf life and limited public interest in the controversy about Mitchell's social posts provides another basis for distinguishing the instant case from Otto. Whether you love him or hate him, Donald J. Trump's activities are (and - sigh - continue to be) newsworthy and, thus, likely to give rise to interest in (and a market for) photos of him. The same cannot be said for Ms. Mitchell, even with her thousands of followers:

"At the moment the plaintiff in Otto took the photograph, it was clear that the photograph would have a market for its contents. News organizations reporting on the President's attendance of the wedding would want to license a photograph of the President in attendance. Here, Plaintiff cannot reasonably claim that this secondary use market, a media firestorm about her friend's controversial social media post, was "traditional, reasonable, or likely to be developed."

Originally Published by Advertising Law Updates

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.