- in Europe

- within Law Department Performance and Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

Executive Summary

Children with medical complexity represent less than 1% of all children in the U.S., but have significant, specialized, and long-term health care needs, accounting for one-third of pediatrics costs in the U.S.1 This group of children have one or more chronic and/or complex medical conditions— such as cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy and seizure disorders—that result in functional limitations and/or dependence on in-home nursing support and medical devices like a ventilator. Care for children with medical complexity is not only costly but also too often difficult for families to access. Yet, without this care, children with medical complexity are at higher risk of emergency room visits, hospitalization, and even moving into an institutional setting, away from their homes, families, and communities.

The well-documented national home care workforce shortage is leaving families of children with medical complexity struggling to balance all of the challenges that come with caring for their child, chief among them finding the right care for their child in their homes.1 Home health agencies, for example, reported turning away over 25% of referred patients due to staff shortages in 2023. When families can't find providers for their children, family members are often forced to leave the workforce to fill the gap, without compensation for the care they provide to their child.2

There is an urgent need to expand access to care delivery models that keep children with medical complexity in their homes and out of costly hospital or institutional settings, while supporting families' financial security. A small but growing number of state Medicaid programs2 are adopting the Family Certified Nursing Assistant (CNA) model to do just that.

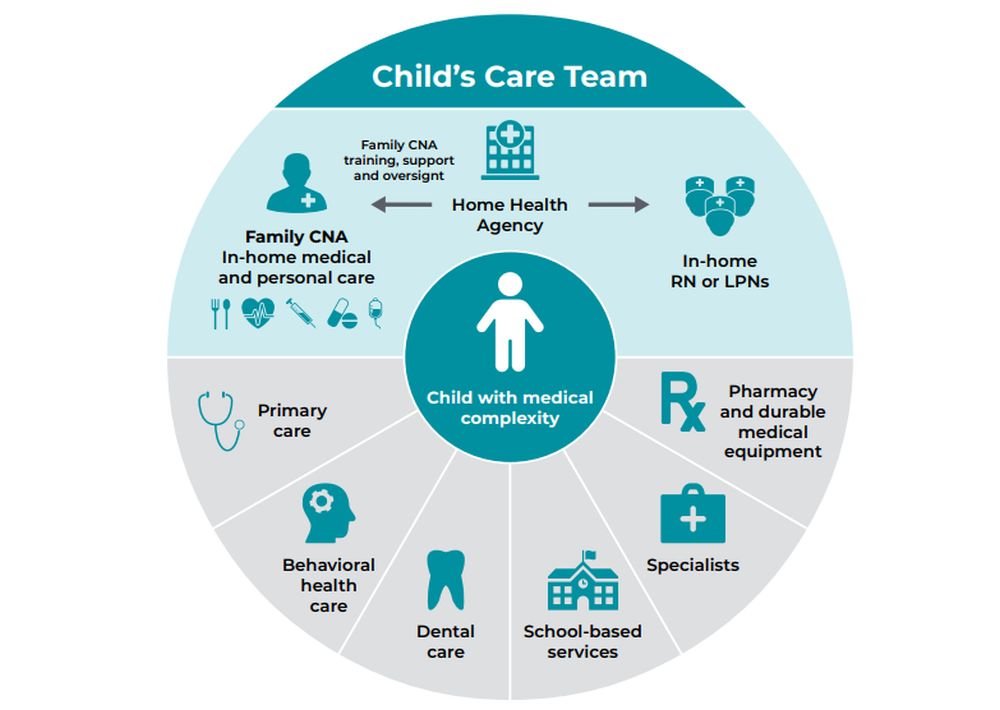

The Family CNA model trains and reimburses family members—including parents, guardians, siblings, aunts, uncles, and grandparents—to provide certain types of home care for children with medical complexity that would otherwise be provided by a registered nurse (RN), a licensed practical nurse (LPN), or a non-family CNA. This care includes low acuity in-home nursing tasks, such as medication administration, gastronomy tube (G-tube) care, or catheter care. Family CNAs are licensed or certified health care professionals that work in concert with other providers on a child's care team, including RNs and LPNs who provide supervision and perform high-acuity tasks, to support their child's medical needs and activities of daily living at home. The unique benefits of the Family CNA model include:

- Addressing critical home care workforce shortages by increasing the number of trained and compensated caregivers and freeing up RNs and LPNs to operate at the top of their credentials and serve more patients.

- Improving the continuity and quality of care for children with medical complexity. Family CNAs receive, at minimum, the same training as non-family CNAs, and in some states receive additional training on skilled tasks such as feeding tube care and tracheostomy care. Additionally, as family members, they maintain a close and lifelong connection to their child.

- Strengthening families' agency and supporting financial security. Giving family members the technical skills and support they need to provide person-centered care while compensating them for their time improves the well-being of the entire family.

The Family CNA model also has cost-saving potential for states, by preventing avoidable or prolonged hospitalizations and by freeing up RNs and LPNs to provide care at the top of their licenses. A recent analysis by the Oklahoma Medicaid agency found that implementing a Family CNA program could save more than $3 million annually.3

There is bipartisan support and momentum at both the federal and state levels to acknowledge the value of family caregivers and better support them as part of a multi-pronged strategy to address the national home care workforce shortage and, in turn, improve care for children with medical complexity. While Medicaid priorities and policies are in a dynamic state, there are actions federal and state policymakers can take to build on that momentum of support for family caregivers and expand access to the Family CNA model. These actions, discussed in more detail in this paper, include:

- Building a coalition of key constituencies, including families and their advocates, providers, nursing boards, and policymakers, to support and design state Family CNA programs that meet the needs of children with medical complexity in their state, proactively address barriers to implementation, and produce positive outcomes.

- Building a coalition of key constituencies, including families and their advocates, providers, nursing boards, and policymakers, to support and design state Family CNA programs that meet the needs of children with medical complexity in their state, proactively address barriers to implementation, and produce positive outcomes.

- Building a coalition of key constituencies, including families and their advocates, providers, nursing boards, and policymakers, to support and design state Family CNA programs that meet the needs of children with medical complexity in their state, proactively address barriers to implementation, and produce positive outcomes.

States that newly adopt the model will have the advantage of learning from existing Family CNA programs as well as other national family caregiver initiatives under way. More families with access to the Family CNA model will mean more families are trained to care for their children with medical complexity while also receiving appropriate support and oversight to provide high-quality care. This, in turn, will mean fewer gaps in care and greater economic security for the entire family.

A Critical Member of the Care Team: Family Caregivers

There are at least 53 million family caregivers in the United States providing informal and, most often, unpaid care to their loved ones.4 Family caregivers provide supports for older adults and people of all ages with disabilities and/or complex medical conditions that are needed for those individuals to continue to live in their homes and communities. Supports from family caregivers can range from assistance with daily tasks, such as feeding, dressing, or bathing, to higher skilled low-acuity medical tasks, such as medication administration or cleaning and using a feeding tube. Often, family caregivers must learn these skills on their own without any formal training or ongoing oversight.5

Without family caregivers, many of the individuals they care for would be forced to seek care in institutional settings, such as nursing homes or inpatient hospitals (often not specifically designed to care for children), where the care is significantly more expensive and can lead to worsening health (e.g., exposure to hospital-acquired infections). In fact, evidence has shown that poor access to home care services increases the risk of prolonged hospitalization and increased costs.6 Put more simply, services provided by family caregivers help keep people out of more expensive settings like hospitals.

Family caregivers can work in partnership with other in-home health care professionals such as nurses, physical, occupational, and speech therapists, non-family CNAs, home health aides, and personal care attendants. These workers are sometimes referred to as the "formal" home care workforce. Family caregivers can be a parent, spouse, child, or other close relative or even a friend or neighbor. What sets family caregivers apart from the "formal" workforce is their personal relationship to and intimate knowledge of the people they care for, which can positively impact an individual's care experiences and quality of care. Not only are family caregivers well positioned to advocate for the person they are caring for, but they may more intimately understand their condition, health status, or behaviors. This can help them to notice changes in their health or wellbeing earlier than other "formal" providers. Such early intervention can prevent or mitigate the need for higher, more costly levels of care in hospitals or other facility settings. Additionally, language and cultural barriers—which have been linked to rehospitalizations for home care patients—are likely rare between a family caregiver and the person they're caring for.7

Family caregivers can also provide a greater continuity of care to their loved ones compared to the formal home care workforce. For example, turnover rates for nursing assistants who provide home care was nearly 80% in 2024; turnover rates for RNs and LPNs who provide home care was 28% and 29%, respectively (2023).8 Every time a new provider is hired, new training and new learning are required—on the part of the caregiver, the individual receiving services, and provider agencies. This creates gaps in access to services that can directly impact care quality and outcomes. On the contrary, individuals receiving home care services from a consistent provider are more likely to avoid hospitalization and emergency department care.9

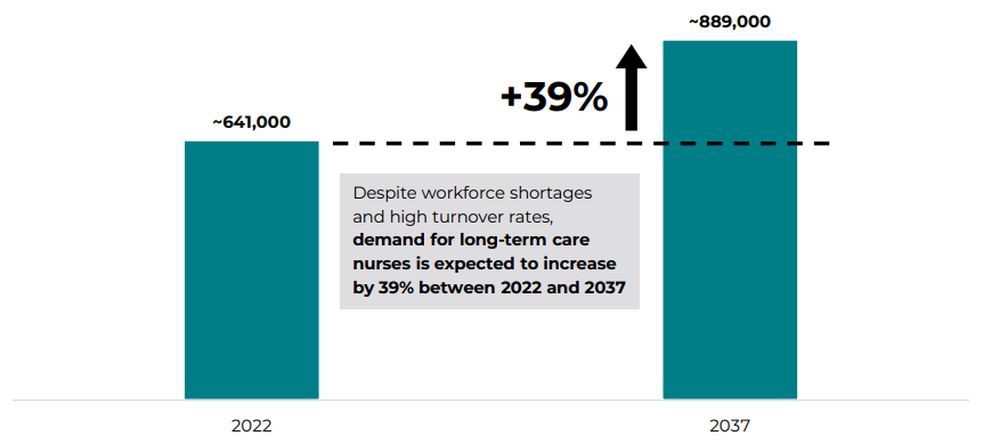

Figure 1: Projected Demand for Long-Term Care Nurses3

Workforce Shortages Are Putting Children With Medical Complexity at Risk and Increasing Health Care Costs

Worker burnout tied to low wages and the high demands of caregiving is driving a nationwide shortage of nurses, home health aides, personal care attendants, and other in-home care providers.10 This shortage is the most significant challenge facing individuals needing long-term care and their families, particularly in rural and frontier states, and it is also driving the increased reliance on family caregivers.11 For families of children with medical complexity, the risks associated with worker shortages are severe.

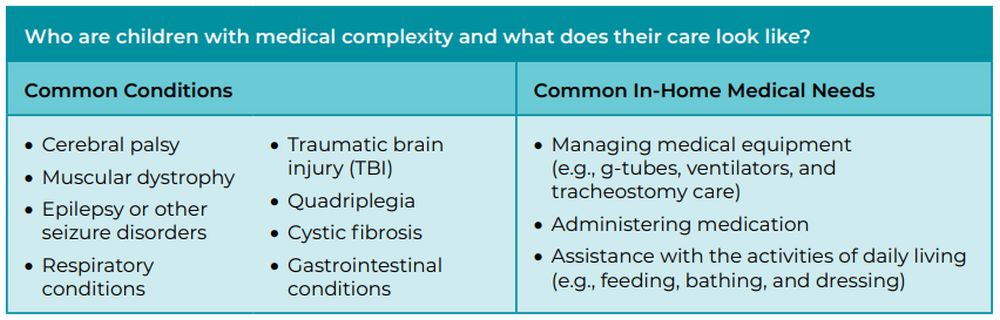

Children with medical complexity are a small population with specialized, intensive, and long-term health care needs.12 While there is no standardized definition for children with medical complexity, they are children who have one or more complex and/or chronic medical conditions—including cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy and seizure disorders—that result in functional limitations and/ or dependence on in-home nursing support and medical devices like a ventilator. Unsurprisingly, children with medical complexity have high health care costs. They make up 1% of children but account for approximately one-third of total pediatric health care costs.13

Table 1: Common Conditions and In-Home Medical Needs of Children With Medical Complexity

Much of the care that children with medical complexity rely on is considered "skilled" care, which puts an added burden on families when providers are not available due to shortages. Family caregivers are often forced to step in or expand their roles to include providing highly technical clinical and non-clinical services and supports to their children, without training, support, or compensation. As a result, family caregivers of children with medical complexity experience particularly high levels of stress, burnout, behavioral health needs, and—if they've had to leave the workforce—financial instability, compared to other family caregivers.14

Nearly half of all children with special health care needs—children at risk of chronic physical, developmental, behavioral, or emotional conditions—have at least some Medicaid coverage to pay for needed services (children with medical complexity are a subset of children with special health care needs; insurance rates for children with medical complexity specifically are unclear). However, this does not insulate them from worker shortages that leave children with medical complexity at risk for worsening health and poor outcomes, particularly emergency department visits and hospitalizations. Many of those children find their hospital stay extended unnecessarily, with poor access to nursing care in the home cited as the top reason for a delay in discharge.15 When children do return home, nursing care may not be available at sufficient levels, forcing family members to step in and try to cover missed nursing care. To do that, family members may need to temporarily take time off from their jobs or leave the workforce altogether (either voluntarily or by being terminated for taking too much time off), which increases financial instability for the family. Family caregivers assuming these tasks without appropriate training and support can lead to a deterioration in the health of the child and readmission to the hospital. It is a traumatizing cycle for children with medical complexity and their families of multiple hospitalizations, disjointed care, and avoidable costs (which are also borne by state Medicaid agencies and other payers).

The Family CNA Model: Improving Care and Supporting Families of Children With Medical Complexity

While family caregivers have always cared for loved ones, including children with medical complexity, the COVID-19 pandemic accelerated the development and expansion of care models that recognize and support the critical role of family caregivers. These models—which generally have bipartisan support—pay, train, and offer other supports (such as counseling and peer-to-peer networking) to people who provide or want to provide in-home services to their loved one.16

States have taken several approaches to paying family caregivers. Among the most innovative models for families of children with medical complexity is the Family CNA model. Under the model, parents or family members of children with medical complexity who qualify for PDN services are trained as a CNA, licensed health aide, or complex care assistant (the title of the role varies state to state). The training is, at minimum, equivalent to the training that other CNAs receive and can include training specifically on the needs of children with medical complexity and on more advanced skills depending on state requirements, such as feeding tube care and medication administration. This approach ensures that care provided by the family CNA is of the highest quality and that family caregivers aren't left to teach themselves how to perform the intensive types of medical services upon which children with medical complexities depend.17

Family CNAs are employed and paid by home health agencies (which may also pay for the training and compensate family CNAs during their training time) so the family CNA isn't forced to forego income in order to care for their loved one. The home health agency is responsible for clinical oversight of the family CNA and quality assurance, which includes regular performance evaluations and monitoring for adherence to care plans. The home health agency also provides family CNAs with dedicated resources for when they have questions about their child's care needs. This infrastructure ensures that care provided by family CNAs complies with state and federal program and regulatory requirements. The home health agency also facilitates billing and payment processes for the services provided, ensuring transparency and accuracy of payment for delivered services.

Family CNAs work closely with other home care professionals, supplementing the specialized nursing services provided by RNs or LPNs. When family CNAs manage lower acuity medical tasks, RNs and LPNs are freed up to operate at the top of their license and can provide care for more higher-acuity patients.

Figure 2: Family CNA Care Model

"A Blessing" for Brittany's Family

Before becoming a family CNA, Brittany always struggled to find high-quality nursing care for her daughter. Brittany had struggled to hold a job due to her daughter's significant medical needs, saying that "having a medically complex child is a 24-hour job." The Family CNA model allowed her to get certified and provide skilled care for her daughter, growing her professional skill set and helping provide financial stability for her family. Even more important, it has allowed her daughter to be cared for by the person that loves her most, eliminated the gaps in state-approved care her daughter experienced due to worker shortages, and reduced her daughter's hospitalizations. Brittany now describes herself as an advocate for the model, sharing information about this opportunity as often as she can with other families who have children with medical complexity.

The Case for Expanding Access to the Family CNA Model

The Family CNA model predates the COVID-19 pandemic but, like other family caregiving models, it is getting a fresh look as families, providers, and states seek improved care options for children with medical complexity. The American Academy of Pediatrics has endorsed family caregiver programs for children with medical complexity like the Family CNA model, highlighting benefits for parents, children, and state Medicaid agencies including improved child health and well-being, better continuity of care, and enhanced family financial stability.18 Additionally, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) issued guidance at the end of the pandemic encouraging states to continue to use available authorities, such as certain Medicaid state plan benefits and home- and communitybased service (HCBS) waivers, to pay family caregivers, which extends to home health agency models like Family CNA.19 In 2022, the National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers was published, implementing the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, & Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act which was signed into law in 2018, during the first Trump Administration.20

"Research shows that when

states enable parents and caregivers of [children with special

health care needs] to be paid for the extraordinary care they

provide to their children, there can be numerous potential benefits

to the parents, child, and state."

American Academy of Pediatrics

The Family CNA model has been fully implemented in seven state Medicaid programs—with some variation in the services the family CNA can provide, the populations that are eligible for family CNA services, and how they title the program and the family caregiver position (see table 2); several additional states have a limited version of the model or are working to implement the model (see figure 2).

To view the full article, click here.

Footnotes

1. The home care workforce shortage is also impacting the ability of seniors and people with disabilities to find the care and support they need to remain in their homes and communities.

2. Medicaid is the largest payer of long-term services and supports (LTSS)—this paper uses the term "long-term care"—in the United States. In 2022, Medicaid paid for 61% of all LTSS spending in the U.S. and 69% of home and community-based services, a subset of LTSS. https://www.kff.org/medicaid/issue-brief/10-things-about-longterm-services-and-supports-ltss.

3. Health Resources and Services Administration Bureau of Health Workforce. Long-Term Services and Support: Demand Projections, 2022–2037. November 2024. https://bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-healthworkforce/data-research/ltss-projections-factsheet.pdf. In this report, long-term care nurses refer to RNs and LPNs that work in both home- and community-based settings and facility-based settings.

1. American Academy of Pediatrics. Children with Medical Complexity. 2024. https://www.aap.org/en/patient-care/childrenwith-medical-complexity/?srsltid=AfmBOoqNisnVhKwMoKRx-8BtY7dt2HIOvv1vls-s8MXNFOR3-60Q28Jn

2. Home Care Association of America and National Association for Home Care & Hospice. The Home Care Workforce Crisis: An Industry Report And Call To Action. March 2023. https://www.hcaoa.org/uploads/1/3/3/0/133041104/workforce_report_and_ call_to_action_final_03272023.pdf

3. Oklahoma Legislature. Senate Fiscal Summary; Senate Bill 56. 2025. https://www.oklegislature.gov/cf_pdf/2025-26%20 SUPPORT%20DOCUMENTS/impact%20statements/fiscal/Senate/SB56%20INT%20FI.PDF

4. The Recognize, Assist, Include, Support, and Engage (RAISE) Act Family Caregiving Advisory Council & The Advisory Council to Support Grandparents Raising Grandchildren. 2022 National Strategy to Support Family Caregivers. September 21, 2022. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/RAISE_SGRG/NatlStrategyToSupportFamilyCaregivers-2.pdf

5. Founders of the Home Alone Alliance. Home Alone Revisited: Family Caregivers Providing Complex Care. April 2019. https:// www.caregiver.org/uploads/2023/02/home-alone-revisited-family-caregivers-providing-complex-care.pdf

6. Roy C. Maynard, M.D., FAAP, and William Wheeler, M.D. American Academy of Pediatrics. Pediatric home care nursing shortage contributes to prolonged hospitalization. December 7, 2016. https://publications.aap.org/aapnews/news/12620

7. New York University. Home Care Patients with Language Barriers at Higher Risk for Rehospitalization. October 27, 2021. https://www.nyu.edu/about/news-publications/news/2021/october/home-care-patients-language-barriers-rehospitalization. html

8. National Association for Home Care and Hospice. Home Care Salary & Benefits Reports. November 8, 2023. https://nahc.org/ home-health-rns-receive-3-88-hourly-rate-increase-in-2023/#:~:text=Oakland%2C%20NJ%2C%20November%202023%20 %E2%80%93,Healthcare%20Compensation%20Service%20(HCS)

9. David Russell, Robert J Rosati, Peri Rosenfeld, and Joan M Marren. J Healthc Qual. Continuity in home health care: is consistency in nursing personnel associated with better patient outcomes? 2011. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/22103703/

10. Barbara Lyons and Molly O'Malley Watts. The Commonwealth Fund. Addressing the Shortage of Direct Care Workers: Insights from Seven States. March 19, 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/mar/ addressing-shortage-direct-care-workers-insights-seven-states

11. Strengthening the Direct Service Workforce in Rural Areas, Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. https://www.medicaid. gov/medicaid/long-term-services-supports/downloads/hcbs-strengthening-dsw-rural-areas.pdf

12. Eyal Cohen, Dennis Z Kuo, Rishi Agrawal, Jay G Berry, Santi K M Bhagat, Tamara D Simon, Rajendu Srivastava. Pediatrics. March 2011. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3387912/

13. Nancy A. Murphy, Justin Alvey, Karen J. Valentine, Kilby Mann, Jacob Wilkes, and Edward B. Clark. Hospital Pediatrics. Children With Medical Complexity: The 10-Year Experience of a Single Center. August 1, 2020. https://publications.aap.org/ hospitalpediatrics/article-abstract/10/8/702/588/Children-With-Medical-Complexity-The-10-Year?redirectedFrom=fulltext

14. American Academy of Pediatrics. Paid Family Caregiving: State Medicaid Pathways For Payment: Advocacy Action Guide for AAP Chapters. 2024. https://files.constantcontact.com/e5552cf9201/c5a0c660-22cd-432a-b786-4c7c04abb9aa.pdf

15. Roy Maynard, Eric Christensen, Rhonda Cady, Abraham Jacob, Yves Ouellette, Heather Podgorski, Brenda Schiltz, Scott Schwantes, and William Wheeler. Pediatrics. Home Health Care Availability and Discharge Delays in Children With Medical Complexity. December 3, 2018. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/30509929/

17. Bipartisan Policy Center. Addressing the Direct Care Workforce Shortage: A Bipartisan Call to Action. December 2023. https:// www.azahcccs.gov/PlansProviders/Downloads/LHA/LHA_RulesDec2021.pdf

18. American Academy of Pediatrics. Paid Family Caregiving: State Medicaid Pathways For Payment: Advocacy Action Guide for AAP Chapters. 2024. https://files.constantcontact.com/e5552cf9201/c5a0c660-22cd-432a-b786-4c7c04abb9aa.pdf

19. Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. All-State Medicaid and CHIP Call. June 6, 2023. https://www.medicaid.gov/ resources-for-states/downloads/covid19allstatecall06062023.pdf

20. 115th Congress. Public Law 115-119. An Act to provide for the establishment and maintenance of a Family Caregiving Strategy, and for other purposes. January 22, 2018. https://acl.gov/sites/default/files/about-acl/2018-10/PLAW-115publ119%20-%20RAISE. pdf

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]