- within Employment and HR, Strategy, Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives and HR

- with readers working within the Insurance, Healthcare and Utilities industries

While discrimination and sexual harassment cases have historically dominated the labor litigation arena, the number of wage and hour cases has risen dramatically over the past decade.1 A wage and hour case is the general description for cases concerning the alleged non-payment of full and timely wages. These cases can be brought in one of three ways: (1) under the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA), in either state or federal court; (2) in state court according to the laws of that state; or (3) directly with the Department of Labor, Wage, and Hour Division. The FLSA contains an "opt-in" requirement, where plaintiffs must actively elect to participate in the class, while state laws generally have an "opt-out" requirement, where claims meeting the requirements of the class are automatically included unless plaintiffs decline to participate in the class. Department of Labor claims are preliminarily reviewed and, if a suspected violation occurred, are registered as a complaint, with an investigation to follow.

These cases, which often involve large numbers of employees and massive datasets, present complex class certification issues. Below, after presenting trends in wage and hour cases, we explain how the use of statistics can help shed light on these issues.

RECENT TRENDS IN WAGE AND HOUR CASES

Wage and hour cases can be categorized into a number of different types, some of which are overlapping. These include:

- Meals and breaks cases, which assess whether employees were allowed to take full and timely meal periods and rest breaks for which they were eligible.

- Overtime cases, which assess whether employees were paid the appropriate rate for overtime work (either more than 40 hours per seven-day week per the FLSA or the requirement specified by the relevant state law).

- Misclassification cases, which assess whether employees were misclassified as exempt from the FLSA or state law requirements—and so were ineligible for overtime or other benefits— when they were in fact operating in the capacity of a non-exempt worker and so should have received these benefits.

- Off-the-clock cases, which assess whether employees were paid the appropriate rate for any "off-the-clock" work (i.e., work performed but uncompensated). One variant of these cases, dubbed "donning and doffing cases," assesses whether employees were paid for the time spent putting on or taking off protective clothing or other uniforms required for the job. Off-the-clock cases are often paired with overtime cases, as plaintiffs assert that the alleged off-the-clock work, if recognized, would have increased the employee's weekly hours above 40.

- Minimum wage cases, which assess whether the aggregate amount employees were paid, divided by the number of hours worked (including any demonstrated off-the-clock work), generated an hourly rate that was below the minimum wage (including any overtime pay for which the employee was eligible).

- Termination pay cases, which assess whether employees received all wages due upon termination (potentially including untaken vacation and personal hours), and whether such payments were made within statutory time limits.

- Processing/penalty wage cases, which assess whether employees did not receive full compensation for time worked as a result of the employer's failure to accurately maintain timekeeping records.

- Tip pooling cases, which assess whether employees were required to share tips with managers who are not eligible to share in pooled tips. Below, we examine trends in the number of wage and hour cases overall, as well as their distribution by geography and by case type.

Wage And Hour Cases Increased Dramatically During The Last Decade

Figure 1. FLSA Filings In US District Courts

January 1, 2000 Through December 31, 2008

Based on complaints tracked by PACER, US District Court filings of FLSA cases has trended up since 2000, with large increases in filings occurring both in 2002 and in 2006.2 Although filings pulled back in 2007, current FLSA filings are still higher than they were prior to 2006. See Figure 1 for FLSA filings in US District Courts.

A recent study examined data over the period October 1, 2007 through March 28, 2008, finding that 1,655 employment-related class actions were brought in either federal or state courts, with 70% (or 1,147 cases) filed in federal court and 30% (or 508 cases) filed in state court.3 A notable exception to this pattern occurred in California, which exhibits a federal/state pattern that is nearly reversed. California was home to 80% (or 407) of all state court cases, while just 137 employment-related class actions (or 12% of all federal filings) were filed in US District Courts in California.4

The Vast Majority Of FLSA And State Cases Have Been Filed In Only A Few States

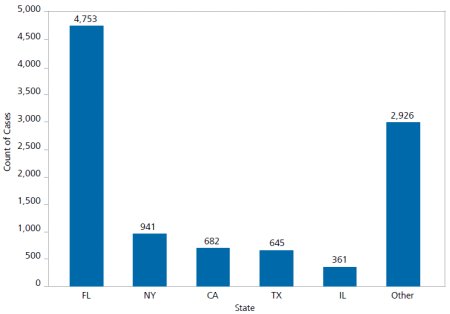

Of the 10,000 FLSA cases filed in US District Courts during the past two years, over 45% were filed in Florida.5 Other jurisdictions with a large number of FLSA filings include California, Illinois, New York, and Texas. Together these five states account for over 70% of the FLSA filings in 2007 and 2008. See Figure 2 for claim filings by state over the past two years.

Figure 2. FLSA Filings In US District Courts, By

State

January 1, 2007 through December 31, 2008

No national database comparable to PACER exists for complaints filed in state court. However, several studies have looked at state court filings in selected jurisdictions. One study reported that "the most significant growth in wage and hour litigation" occurred in the state courts, particularly in California, Florida, Illinois, New Jersey, New York, Pennsylvania, and Texas, but did not provide any statistics on the number of new filings in each jurisdiction.6 The finding for California was corroborated by a study initiated by the Administrative Office of the Courts in California, covering class action litigation from 2000 through 2005.7 Over this six-year period, although individual civil actions filed in California fell by more than 15%, class action filings increased 63%.8 The biggest increase came from the employment-related cases. After reviewing a random sample of the class action filings, the authors concluded that employment cases represented only 17% of cases filed in 2000, but 42% of cases filed in 2005.9

Most Wage And Hour Cases Involved Alleged Overtime And Off-The-Clock Violations

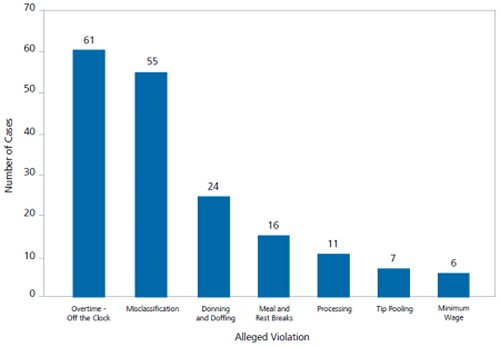

To assess the types of wage and hour allegations, we compiled a database of state and federal wage and hour case filings for approximately 180 cases reported in the publication Employment Law 360, as well as in news articles obtained from Factiva over the period 2006 through 2008. For each case, we recorded the filing date, jurisdiction, and type of wage and hour case.10 All but 12 of the cases were filed in federal court.11

Most of the cases filed involved allegations of overtime and off-the-clock violations, with misclassification cases the next most prevalent. See Figure 3 for case filings by type of alleged violation.

Figure 3. Wage And Hour Case Filings By Type Of Alleged

Violation

January 1, 2006 through December 31, 2008

This filing pattern matched that of the complaints filed with the US Department of Labor. Of the complaints investigated by the US Wage and Hour Division in 2008, "the most frequently cited violation (in terms of the number of employees affected) was the payment of straight-time pay for overtime-hours worked."12 The next most frequent violation involved off-the-clock work. Similarly, over half of the employment cases reviewed in the California class action study (2009) cited violations relating to "overtime pay and general wage violations."13

Another category with a substantial number of FLSA cases involved meal and rest break allegations. In California, these cases were first filed in significant numbers in 2003, where meal and break-related cases increased from virtually zero in 2002 to over 10% of employment cases in 2003.14

USING STATISTICS TO ASSESS THE RELEVANCE AND RELIABILITY OF DATA IN WAGE AND HOUR CASES

For a class action to be certified by the courts (and hence allowed to proceed), plaintiffs must first satisfy Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, including four requirements under Rule 23(a) and at least one under Rule 23(b). If the plaintiffs are instead pursuing a collective action, they must satisfy the requirements of 29 U.S.C. §216(b).

The four requirements under Rule 23(a) are:

- Numerosity – "the class is so numerous that joinder of all members is impracticable;"

- Commonality – "there are questions of law or fact common to the class;"

- Typicality – "the claims or defenses of the representative parties are typical of the claims or defenses of the class;" and

- Adequacy of representation – "the representative parties will fairly and adequately protect the interests of the class."15

To satisfy Rule 23(b), plaintiffs must show that at least one of the following applies:

- Separate actions would create risk of a) inconsistent or varying outcomes with respect to individual class members, which would create incompatible standards for the party opposing the class, or b) individual outcomes, which would affect other interests that were not a party of the outcome or impair their ability to protect their interests; or

- The party opposing the class acted in a manner that was applicable to the entire class such that the appropriate outcome would be "injunctive relieve or corresponding declarative relief with respect to the class as a whole"; or

- "The questions of law or fact that are common to the class members predominate over questions affecting only individual members and that a class action is superior to other available methods for the fair and efficient adjudication of the controversy."16

In employment cases, plaintiffs typically attempt to certify the class using either Rule 23(b)(2) or Rule 23(b)(3), in addition to the four requirements under (23)(a).17

The approaches to certification under a collective action have been more disparate. For the collective action to proceed, the class must be "similarly situated." Some courts have required plaintiffs to meet the same criteria as under Rule 23, allowing discovery to occur in the process. More typically, courts have followed a two-step process, allowing "conditional" certification initially, with the possibility of decertifying the class following discovery. Conditional certification allows the plaintiffs to send notices to the class members, enabling them to opt into the class.18 According to one source, courts are unlikely to determine that certification is improper based on the merits of the defendant's case. Instead, successful arguments against conditional certification have hinged on demonstrating variability among class members (based on, for example, type of jobs, location, and managers) or in instances in which it is determined that individualized review would be necessary.19

For example, in the case Johnson v. Big Lot Stores, Inc., plaintiffs alleged the misclassification of employees as exempt from FLSA overtime requirements. Although the collective action received conditional certification, after extensive discovery (and several attempts at decertification), it was eventually decertified by the court because of "wide differences in employment experiences between individual employees and the lack of common proof applicable to the class as a whole."20 Johnson v. Big Lot Stores, Inc. was an unusual case in that it was decertified after the case had gone to trial. During trial, plaintiffs submitted the results of a survey of the almost 1,000 opt-in claimants in the case. The judge ruled based on the results of the survey that while at a "high level" the plaintiffs' job descriptions were similar, at an individual level there was substantial variability in responsibilities across employees and even for a given employee over the course of the work week or work day.21 As a result of this variability, the Court ruled that the case could not survive as a collective action.22

Similarly, in Roussell v. Brinker International, Inc., a case in which plaintiffs alleged that Chili's violated tip-sharing policies, the court decertified the collective action because the "lawsuit involve[d] critical questions of fact that vary from plaintiff to plaintiff and restaurant to restaurant, and does not allow resolution of the case in a single collective proceeding."23 In that case, plaintiffs had proposed a three-phase trial plan: phase one would determine whether certain managers were eligible to share in tips; phase two would be a test trial for 20 to 50 opt-in plaintiffs for both liability and damages; and phase three would be a series of mini-trials for the remaining 3,000 plaintiffs.24 The court determined that because of the variability of issues across claimants, the plaintiffs' trial plan left the possibility that in phase three there could be as many as 3,000 separate trials.25 As such, the action failed as a collective action.

Using a proper statistical review of the available data in wage and hour litigation, experts can assess whether those data are sufficient to assess class-wide allegations reliably. If not, individualized review may be necessary. Even if the data are determined to be sufficient to assess whether a potential violation occurred, variability in the patterns of those alleged violations may suggest that innocuous factors, rather than any misconduct by management, are at work or that conflicts exist that will prevent certification of a class or collective action.

Evaluating The Available Data

A variety of electronic data has been introduced in wage and hour cases in an attempt to assess whether employees were paid full and/or timely wages. These include:

- Timekeeping records, which may include scheduled hours, swiped hours (regular as well as overtime/premium pay hours), hours not worked (e.g., vacation and personal time), and manager or employee modifications;

- Payroll records: wage rate, which may included type of hours paid (e.g., regular or overtime), payroll deductions (including taxes), cumulative earnings, as well as accrued vacation and personal time;

- Cash office logs, which record cash payments made to employees at the store level;

- Cash register transactions, which reflect transactions that occurred on a particular register;

- Hand-held scanning device logs, which reflect the results of inventory scanning; and

- Other electronic records, which may include, for example, usage of computer software (such as online training), phone, and security systems.

Most cases rely on at least one of the first three sources, while the second three are specific to particular industries (e.g., restaurants and retailers). While many companies maintain such electronic business records, it is important to recognize that those records were not created to answer questions that arise in litigation and may not be suitable or relevant for such purposes. Using statistics to answer a number of questions, including the two questions detailed below, can help assess the reliability of such data.

Does The Data Proposed Provide All Information Needed To Assess Allegations?

The data proposed for use in wage and hour litigation may not provide all of the information needed to evaluate the allegations. For example, some data pertinent to the litigation may not be contained in electronic databases or data printouts, but rather in the employees' personnel files. If so, it may be necessary to conduct an individualized review, manually pairing the electronic data with non-electronic data, such as personnel records or interviews with relevant personnel. Consider a case where plaintiffs allege, based on data obtained from electronic records only, that the company failed to pay its employees their full wages due upon termination. However, in addition to electronic payroll records, the company also retained detailed paper personnel files for each employee at that employee's store. By relying solely on the electronic record and ignoring those other records, an expert would miss facts relevant to the case. For example, a review of personnel files for a sample of purported class members might show that they were not in the store at the time of termination, had failed to return to the store to collect their final pay and did not respond to repeated attempts at contact by the company. A statistical review of the amounts allegedly owed to these employees might show that they were very small, providing a potential explanation for why those employees chose not to return to the store to collect the payout. Statistical analysis of the larger class might show that a large proportion of alleged class members similarly were not present at the time of termination and were owed small amounts. While an analyst might infer that these employees also failed to respond to attempts at contact, individualized review would be needed to understand the facts and circumstances surrounding the alleged failure to pay termination wages and reach a definitive conclusion.

Will Proposed "Surrogate" Data Yield Reliable Results?

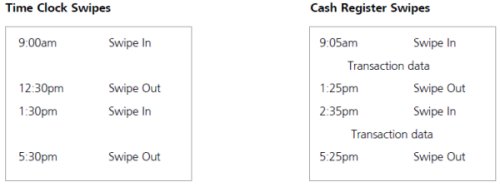

In the absence of records that directly address the alleged wage deficiencies, some experts have attempted to use "surrogate" data to arrive at conclusions about the size of the alleged class or the amount of alleged damages. For example, experts have attempted to compare data on log-ins and log-offs of cash registers with swipes in and out of the timekeeping system to identify periods of alleged off-the-clock work. Analysis of other business record systems, such as inventory systems, security access systems, operational reporting systems, and financial reporting systems, has also been proposed. However, statistical analysis may show that in linking data systems for litigation that were not already linked for business purposes, it is possible to reach erroneous conclusions and that the use of surrogate data may not generate reliable results. Here are several examples of such erroneous conclusions that might be reached with improper use of cash register data.

Systems That Are Not Linked Can Create The Appearance Of Violations When None Exist

Consider a case where plaintiffs allege they were forced to work through their meal periods. An expert might attempt to compare time swipes in the timekeeping system with those in the cash register records to identify such periods, attempting to show that employees were operating the cash register when they had swiped out of the timekeeping system. However, this comparison can generate meaningless results in a variety of circumstances. Frequently, for example, employees take meal periods but forget to swipe for them. In such circumstances, the procedure is typically for them to ask a manager to insert a meal period into the timekeeping system. Errors or even small imprecision in this process can create the appearance of off-the-clock work where none existed.

For example, suppose an employee had taken a meal period from 1:30 to 2:30pm but had forgotten to swipe. When reporting the omission to his manager, he misremembered and told the manager the meal period had been from 12:30 to 1:30. See Figure 4 for a sample comparison of data recorded in the time clock system with similar data recorded in the cash register system in such a situation.

Figure 4. Comparison Of Swipes With Meal Period Inserted At The Wrong Time

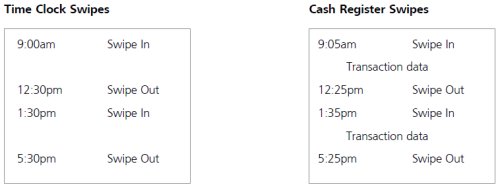

Comparing the two data sets above, an expert might conclude that the employee had a 55-minute period of off-the-clock work from 12:30pm through 1:25pm. However, if the data were corrected to insert the meal period at the proper time, the apparent off-the-clock work disappears. See Figure 5 for a corrected comparison.

Figure 5. Comparison Of Swipes When Systems Are Correctly Synchronized

It is important to realize that, in this situation, regardless of whether the meal period was inserted at the correct time, the employee was paid the right amount. He should have been paid for a 7.5-hour shift, and not paid for a 60-minute meal period, which is what is shown to have occurred in either Figure 4 or Figure 5. The company's records, while accurate for business purposes, generate misleading results when they are used for litigation purposes.

Such situations are not uncommon. Meal periods insertions or other edits to the timekeeping system are likely to occur regularly and, even if just a few minutes off, can create the appearance of off-the-clock work where none existed. Similarly, the clocks across different systems may not be synchronized due to power outages, battery failures, daylight savings time adjustments, or other reasons. Statistical analysis showing that alleged periods of off-the-clock work are generally only a few minutes can provide evidence consistent with such asynchronicity and suggest that periods of alleged off-the-clock work may not have existed.

In the situations described above, a simple comparison of the two datasets produced an apparent violation when no actual violation occurred. These examples highlight the need for rigorous statistical analysis to determine the appropriate way, if any, to link relevant datasets and to assess whether the results produced are reliable. If not, individualized review will again be required.

Surrogate Data Alone May Not Be Sufficient To Determine If An Alleged Violation Occurred

An apparent violation observed in "surrogate" data may not be sufficient to determine whether an actual violation occurred. In cases involving alleged meal period and rest break violations, for example, experts may attempt to calculate the number of employees with a missed time clock swipe and assume that the missed swipe indicated a missed meal period or rest break. Without more information, however, there is not sufficient data to determine that a missed swipe indicates an involuntarily missed meal or break. Alternative explanations might be:

- The employee may have forgotten to swipe or swiped imprecisely (either slightly after or slightly before the break began or ended);

- The meal or break may have been skipped voluntarily; or

- The employee may not have been eligible for a meal or break because of the length of the scheduled shift.

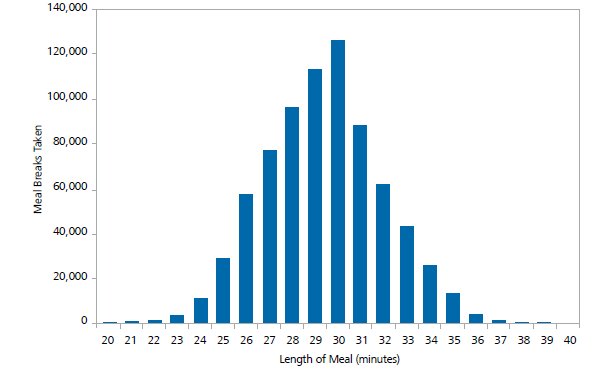

Consider a case where employees allege they were not given full 30-minute meal periods. Experts may attempt to use the timekeeping records to identify any meal period shifts that are less than 30 minutes and assert that each instance represents a situation where the employee was involuntarily required to return to work early from his/her meal period. However, a statistical review of the timekeeping data might reveal that while many meal periods are exactly 30 minutes long, employees frequently swiped in or out for periods both slightly shorter and slightly longer than 30 minutes. See Figure 6 for an example of employees recording meal breaks between 20 and 40 minutes long.

Figure 6. Meal Breaks By Duration, 20 Minutes Through 40 Minutes

In the chart above, over 95% of employees are shown to have swiped in or out within five minutes of the 30-minute mark. While the short meal periods may have been shortened involuntarily, because many meal periods longer than 30 minutes also exist, this statistical review instead suggests that such patterns are evidence of imprecision in swiping by employees. Without additional information, an expert cannot tell from the electronic data alone the reason for the imprecise time swipes, and whether the observed swiping patterns indicate any violation of state or federal laws.

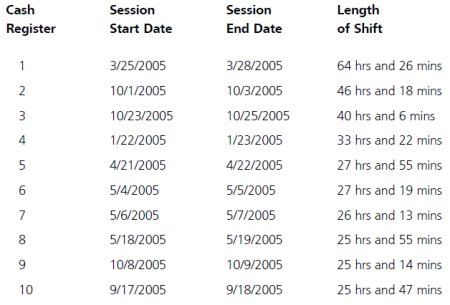

A statistical review of outliers in the data may suggest other reasons that the surrogate data are unreliable. For example, a review of cash register logs may reveal that some employees appear to have been logged on to cash registers for more than 24 hours at a time. See Figure 7.

Figure 7. Cash Register Swipes Lasting Over 24 Hours

One explanation for such occurrences, provided via interviews and testimony by employees and their managers, is that employees use one another's IDs to operate the cash register. If so, it is unreliable to assume that any period of off-the-clock work can be identified by locating periods when an employee's ID is shown as operating a cash register when that employee is not shown as being logged into the timekeeping system. What appears to be off-the-clock work may simply be a second employee (one who is logged into the timekeeping system) operating the cash register under the ID of the first employee. While such problems are revealed through an analysis of statistical outliers (such as shifts exceeding 24 hours), simply excluding such outliers from any calculation of alleged off-the-clock work does not remedy the unreliability of the approach. The existence of such anomalous entries indicates that the cashier logs cannot be used to identify any periods of off-the clock work if, in this case, the practice of using a register activated by another employee was pervasive.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM VARIABILITY IN THE PATTERNS OF ALLEGED VIOLATIONS?

Below, we demonstrate through a series of examples that variability in the patterns of the alleged violations in wage and hour litigation may be inconsistent with any classwide or corporate intent to deprive employees of full and timely wages, or may indicate that conflicts exist among class members.

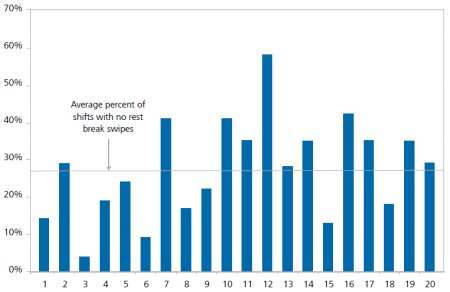

Consider a defendant with 20 factories that is faced with a class action alleging it allegedly failed to provide employees with rest breaks for which they were eligible. An expert might generate an aggregate analysis of the timekeeping records showing that there were no rest break swipes on 25% of break-eligible shifts across all factories. However, looking at this statistic by factory might show that the percent of break-eligible shifts with missed rest break swipes varied significantly, ranging from a low of less than 5% of shifts at one factory to a high of almost 60% at another. See Figure 8 for patterns of rest break swipes at different factories.

Figure 8. Percent Of Shifts With No Rest Break Swipes By Factory

Rather than suggesting a company-wide policy to deprive employees of their rest breaks, this variability suggests that other innocuous factors are likely to explain why the patterns of alleged violations vary. For example, whether the time clock in the factory is conveniently placed may affect whether employees choose to swipe for rest breaks (which are typically paid). The tenure of the workforce may be another factor that affects swiping behavior, though the direction is unclear. Newer employees who have recently gone through orientation training may swipe more accurately or veteran employees, who are more familiar with the process, may remember to swipe more regularly. Given the existence of such innocuous factors, individualized review may be needed to determine whether any particular instance of a missed rest break swipe is an indication of an involuntarily missed rest break. At a minimum, the variability indicates that the factors affecting the rest break swiping appear to be different at each factory, suggesting differences among the putative class members that may prevent class certification.

Next, consider a case against a defendant in the consumer goods retail sector, alleging the company failed to pay overtime. An expert might attempt to extrapolate from a sample of workers who had been paid overtime, assuming that the entire class had a similar proportion of overtime hours as the workers in the sample. Here again, however, if the data is examined by store and by time period, significant variability may be shown to exist in the amount of overtime worked by employees in the sample. For example, the amount may differ between stores in commercial and residential neighborhoods, where the hours of store operation were different. Moreover, corporate-wide changes in the proportion of full-time and part-time employees may have occurred during the sample period, such that more overtime was worked in some sub-periods than others. Further investigation may reveal that rather than being wide-spread, it was only those employees working for a handful of managers who had not received the overtime to which they were entitled. Here again, then, the variability in the data suggests that further investigation is needed to assess whether any classwide violations had occurred, and extrapolation from a sample that does not take into account this variability can lead to erroneous conclusions.

Finally, consider a defendant who hired a group of brokers as outside salespeople, and classified these workers as exempt. Suppose plaintiffs in a class action challenged this classification, claiming that the brokers did not customarily and regularly engage in sales away from the employer's place of business, and thus should not have been classified as exempt and should have been paid overtime wages. An expert might survey brokers in the city of the company's headquarters to determine the average amount of time the workers spent traveling to customers' homes and offices and the time spent working at the employer's place of business. However, a fuller review might show variability across brokers in urban locations, as well as between brokers in urban and rural locations. Some urban brokers might have traveled very short distances to visit customer sites, while some brokers in rural areas had longer travel times that kept their work primarily out of the employer's place of business. However, some brokers in rural areas may have chosen to do most of their work from their place of business via email, whereas urban brokers may have tended to go out to meet customers in person. In either case, any survey that focused only on the urban area near the company's headquarters would miss potential variation in the alleged class and lead to erroneous conclusions about the number of employees who may have been misclassified. At a minimum, a properly stratified survey would be necessary to capture the differences across types of workers.26

CONCLUSION

Wage and hour cases are naturally data intensive—plaintiffs frequently claim that the alleged violations covered many employees over multiple years, with potential violations being measured in minutes worked over the period. Data that has been collected and retained for business purposes is often presented in these cases as evidence that an alleged violation has occurred. While companies may have retained thousands of data records, making it tempting to assume that the data, by its magnitude alone, must be useful in the litigation, such an assumption may be incorrect. As demonstrated above, before any conclusion can be reached, it is necessary to assess whether the available data can be used to answer the questions raised in the litigation.

A detailed statistical analysis may reveal that the available records are insufficient to evaluate the allegations, requiring that individual review is necessary. In such a situation, the court may determine that the class cannot be certified. Moreover, even if the electronic records indicate potential violations, it is necessary to investigate variability in the pattern of alleged violations. Any aggregate analysis that does not account for the drivers of this variability will produce unreliable results, as such variability may demonstrate that factors other than the alleged misconduct by management or the company are at work. If the factors leading to apparent violations differ among claimants, the defendant may not be able to pursue a common defense against, nor the plaintiffs a common case for, all of the claims and the court may determine that the class or collective action cannot be certified.

As the number of wage and hour cases continues to rise, the need for rigorous statistical analysis of the underlying data will become increasingly important.

Footnotes

* The authors would like to thank Janeen McIntosh, Daniel Steinberg, and Yunus Jaffrey for their assitance.

1. See, Roberts, Sally, "Explosion of class action lawsuits focus on wage and hour violations," Business Insurance, November 5, 2007.

2. Data obtained from querying complaints in the PACER database. The total number of FLSA complaints collected by PACER is slightly less than the total number of FLSA cases reported by the US Courts Administrative Office. The US Courts reports filings over from October 1 through September 30 each year. When we compared the complaints filed in PACER over the same time period ending in 2008, the PACER totals were 1.4 percent lower than the US Courts reported totals. In this paper, we have reported the PACER totals so that we can report the data by calendar year and by state.

3. See Mathiason, Garry G., Fermin H. Llaguno, Brian R. Dixon, Krista Stevenson Johnson, J. Kevin Lilly, Lisa A. Schreter, Tammy D. McCutchen, Marlene S. Muraco, Tyler M. Paetkau, and Douglas E. Smith, "Total Wage and Hour Compliance: An Initiative to End the Wage and Hour Class Action War," Working Paper, Littler Mendelson, 2008.

4. Id.

5. Based on data obtained from PACER on FLSA complaints filed each year in each state.

6. See "Annual Workplace Class Action Litigation Report: 2008 Edition," Seyfarth Shaw, LLP, 2008 and See "Annual Workplace Class Action Litigation Report: 2009 Edition," Seyfarth Shaw, LLP, 2009. The 2009 study identifies Massachusetts as another state with significant growth in wage and hour cases.

7. See Hehman, Hilary, "Findings of the Study of California Class Action Litigation, 2000-2006," Administrative Office of the Courts, Office of Court Research, March 2009. The study included the following courts: Superior Court of California, Counties of Alameda, Contra Costa, Los Angeles, Orange, Riverside, San Bernadino, San Diego, San Francisco, San Mateo, Santa Clara, Sonoma, and Ventura. According to the study, these courts accounted for 75.2% of statewide civil filings. The state courts reported 3,711 class actions filed from 2000 through 2005 (these numbers were estimated for courts missing data and reduced to remove cases that misclassified as class actions.) A more detailed study was performed on a random sample of 1,500 of the class actions filed over this time period. The statistics on the types of cases filed are based on the sample results.

8. See Hehman (2009), p. 3-4.

9. See Hehman (2009), Appendix A.

10. The aggregate statistics available from the US District Court do not break the FLSA filings down by type of alleged violation.

11. For three of the 12 cases, there was inadequate information contained in the article to determine whether the cases were filed in state or federal courts.

12. See "Wage and Hour Collects $1.4 Billion in Back Wages for Over 2 Million Employees Since Fiscal Year 2001," US Department of Labor, Employment Standards Administration, Wage and Hour Division, December 2008.

13. See Hehman (2009), p. 7.

14. See Hehman (2009), p. 8.

15. See Rule 23 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure.

16. Id.

17. See Seyfarth Shaw (2009), p. iv.

18. Id., p. v.

19. Id., p. vi.

20. See John Johnson et al. v. Big Lot Stores, Inc., (E.D. LA., June 20, 2008), p. 49.

21. Id., p. 30.

22. In the ruling, the judge observed that there were likely some employees who were clearly misclassified, while there appeared to be other employees that had been correctly classified. As a collective action, neither the plaintiffs nor the defendants could adequately present their case for or defend it against all claimants. Id., p. 55.

23. See Roussell v. Brinker International, Inc., (S.D., TX, September 30, 2008), p. 5.

24. Id., p. 2

25. Id., p. 5.

26. While stratification can address underlying differences across groups, breaking a survey into a number of small groups may lead to issues with the sample size of the survey: there will be a trade-off between the number of groups included within a stratified sample and the precision with which the results are measured. If the workers are divided into many small groups, there may be too few workers in each subset for an expert to draw conclusions that can be reliably generalized back to the population of all potentially affected workers in the class. In such a case, only individualized review may generate a reliable result.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.