B. Treaty Claims/Contract Claims – "Umbrella Clauses"

The question has arisen in a number of ICSID arbitrations whether the ICSID tribunal has jurisdiction to resolve claims based on a breach of contract as opposed to claims amounting to breaches of international law standards. The relevant contract may frequently include a jurisdiction clause which refers contractual disputes to another forum.

In Lanco International Inc. v. Argentine Republic28 the underlying contract between the investor and an agency of the Argentine government contained an exclusive jurisdiction clause submitting contractual disputes to a domestic administrative court in Argentina. The tribunal relied on Article 26 of the Convention which provided that consent to ICSID arbitration is "to the exclusion of any other remedy". The tribunal held that the exclusive jurisdiction clause in the contract did not prevent the submission of disputes to ICSID. Moreover, the tribunal considered that the contractual agreement to submit disputes to an "administrative" tribunal could not be considered a previously agreed dispute-settlement procedure.

In Vivendi v. Argentina29 the concession contract also contained a submission to the administrative courts in Argentina but the claims went beyond the scope of the concession agreement. The ICSID Annulment Committee drew a distinction between claims based on a breach of contract and claims based on breaches of treaty standards, such as a failure to ensure fair and equitable treatment and expropriation.

"In a case where the essential basis of a claim brought before an international tribunal is a breach of contract, the tribunal will give effect to any valid choice of forum clause in the contract [but] where the "fundamental basis of the claim" is a treaty laying down an independent standard by which the conduct of the parties is to be judged, the existence of an exclusive jurisdiction clause … cannot operate as a bar to the application of the treaty standard."

The tribunal observed that a state could breach a treaty without breaching a contract, and vice versa.

Some treaties may elevate breaches by a state of an investment contract with a qualifying investor to the status of a treaty violation by means of an "umbrella clause"; for example, "each Contracting Party shall observe any obligation it has assumed with regard to specific investments in its territory by investors of the other Contracting Party30. Current arbitral jurisprudence allows submission to investment treaty arbitration of claims based on a violation of the applicable treaty and, depending on the wording of the treaty, of other claims including those based on alleged violation of the parties’ contract.

Two recent ICSID arbitrations illustrate the tension between a literal interpretation of the relevant BIT provisions and a wider contextual approach.

In SGS (Societe Generale de Surveillance S.A.) v. Pakistan31 the parties had entered into a pre-shipment inspection agreement (the "PSI Agreement") providing for all claims to be resolved by arbitration in Pakistan. In 1998 SGS commenced proceedings in the Swiss courts alleging Pakistan’s unlawful termination of the PSI Agreement. Those claims were eventually dismissed. Pakistan commenced arbitration against SGS under the PSI Agreement arbitration clause in 2000 and related proceedings were brought in the Pakistan courts. In 2001 SGS filed a Request for Arbitration at ICSID under the Switzerland-Pakistan BIT. Pakistan objected to the ICSID tribunal’s jurisdiction on the basis (inter alia) that the dispute arose out of a contract rather than under the BIT. However, SGS asserted that the contractual disputes were elevated to treaty disputes by virtue of the "umbrella clause" at Article 11 of the BIT which provided:

".. either contracting party shall constantly guarantee the observance of the commitments it had entered into with respect to the investments of the investors of the other contracting party."

The tribunal accepted that a literal reading of Article 11 would support SGS’s position but rejected SGS’s argument:

"As a matter of textuality therefore, the scope of Article 11 of the BIT, while consisting in its entirety of only one sentence appears susceptible of almost indefinite expansion."

The tribunal refused to attribute consequences to Article 11

".. so far-reaching in scope, and so automatic and unqualified and sweeping in their operation, so burdensome in their potential impact upon a Contracting Party"

i.e. the effect that any alleged violation of an unlimited number of state Contracts and other municipal law instruments could be treated as a breach of the BIT. Also, if investors were able to use an umbrella clause to elevate contract claims to BIT claims the tribunal reasoned that they would be able to nullify the effect of dispute resolution provisions contained in state contracts. Rather, the tribunal held that:

"Article 11 of the BIT should be read in such a way as to enhance mutuality and balance of benefits in the inter-relation of different agreements located in differing legal orders."

The tribunal in SGS v. Philippines32 reached an opposite conclusion on the meaning of the applicable umbrella clause. SGS wished to pursue claims for monies due under a comprehensive import supervision services agreement (the "CISS Agreement"). Article X(2) of the Switzerland-Philippines BIT provided:

".. each Contracting Party shall observe any obligation it has assumed with regard to specific investments in its territory by investors of the other Contracting Party."

SGS asserted this "umbrella clause" elevated contract claims into treaty claims. The tribunal adopted a literal interpretation of Article X:

".. interpreting the actual text of Article X(2), it would appear to say, and to say clearly, that each Contracting Party shall observe any legal obligation it has assumed …"

However the tribunal did not follow the literal meaning of Article X to its full extent:

"Article X(2) makes it a breach of the BIT for the host state to fail to observe binding commitments, including contractual commitments, which it has assumed with regard to specific investments. But it does not convert the issue of the extent or content of such obligations into an issue of international law."

Thus, whilst the ICSID tribunal accepted jurisdiction under the BIT to enforce contractual obligations, the extent or content of those obligations fell to be determined pursuant to the dispute resolution provisions in the CISS Agreement. The majority of the tribunal granted a stay to allow the specified tribunal (the Philippine courts) to hear and decide those issues.

(In a dissenting Declaration the claimant’s party-appointed arbitrator, Professor A. Crivellaro, expressed the opinion that the ICSID tribunal had jurisdiction over all aspects of the contractual claims, including the extent or content of the contract obligations, since:

"… the right to select, amongst the attractive forums made available by the BIT, the forum that the investor deems the most suitable to him .. the really innovating contribution of a BIT is given by the investor’s privilege to choose a preferential forum amongst those offered by the host state after the dispute has arisen ..").

C. Parallel proceedings/conflicting decisions

There is a growing awareness in investment treaty arbitrations of the possible difficulties that may arise from parallel proceedings arising from the same or similar events between the same or similar parties.

Parallel proceedings often involve the same set of facts, the same applicable law arising under different BIT’s being determined by different tribunals. The dramatic proliferation of investment treaties between states has greatly increased the options available to aggrieved investors. The recent notorious cases of CME v. Czech Republic and Ronald Lauder v. Czech Republic33 resulted in two arbitration awards reaching different conclusions based on the same set of circumstances, albeit the arbitrations were initiated by different parties under two separate investment treaties.

The tribunal in Joy Mining Machinery Ltd. V. Egypt34 expressed the position commonly adopted by international arbitration tribunals:

"There has been much argument regarding recent cases, notably SGS v. Pakistan and SGS v. Philippines. However, this Tribunal is not called upon to sit in judgment on the views of other tribunals. It is only called to decide this dispute in the light of its specific facts and the law, beginning with the jurisdictional objections."

This approach is notwithstanding that the decisions of other tribunals are routinely referred to before other tribunals and cited by the parties in argument. Whilst prior decisions in international investment arbitrations have no strict precedent effect, regard is had to relevant decisions such that the development of an international arbitral jurisprudence may be observed.

Res judicata and lis pendens have been recognised as general principles of international law. Res judicata is a claim, issue or cause of action which is the subject of a judgment, award or other determination considered final as to the rights, questions and facts which are the subject of the dispute. Re-litigation or reconsideration of the particular matters decided, between the same parties, is generally barred, principally on public policy considerations. A "triple identity" test is normally applied; of parties, cause and subject matter.

Lis pendens (suit pending) operates to prevent two juridical bodies dealing with the same dispute at the same time, on similar public policy grounds i.e. to prevent multiplicity of actions and to ensure legal certainty.

There seems to be a widespread acceptance that arbitral awards may have res judicata effect.35 The Iran U.S. Claims Tribunal has observed:

"As to the alleged risk the Respondents could be subject to multiple liabilities, the Tribunal notes … the principles of res judicata or estoppel would bar Amoco in most if not all, legal systems from successfully prosecuting a claim, the merits of which have finally been determined by this Tribunal".36

Many commentators believe that addressing the problem of such multiple proceedings is likely to be a major challenge for investor-state arbitration in the near future37.

The Czech Republic, following its experience in the CME/Lauder arbitrations has recently announced its intention to terminate or re-negotiate its investment treaties with other EU members, ostensibly to bring these treaties into conformity with EU law. The Czech Finance Ministry has indicated that to this end it will also seek to make changes to some 40 BIT’s with non-EU countries. Amongst the proposed changes is the elimination of treaty protection for indirectly-held investments.

Some of these conflicts might be addressed by consolidation of proceedings or the joinder of additional parties. However, such consolidation or joinder will normally require the agreement of the parties and such agreement will be difficult to obtain.38

Under Article 1126 of NAFTA separate claims involving common question of fact and law may be consolidated if it is "in the interest of the fair and efficient resolution of those claims" to bring them under the purview of a single tribunal. This has recently occurred in the case of ongoing NAFTA arbitrations brought by a number of Canadian forestry products companies against the US, under a "Consolidation Tribunal" made in November 2005 at the request of the US government39. In making its order, the first to order consolidation of parallel NAFTA investor-state arbitrations, the NAFTA Consolidation Tribunal specifically acknowledged the controversy caused by the conflicting CME/Lauder arbitrations.

D. Appellate body

Possible solutions to the issue of conflicting or inconsistent arbitral decisions have included suggestions for a new investment arbitration appellate body:

"The case for an integrated system of administering international justice is a strong one, not least in terms of the consistent development of the law. It is strongly arguable that cases are better decided by judges of experience than by arbitrators selected ad hoc for the purpose of a single case. Arbitration is, however, an important component of the international system and cannot be done away with. We should contemplate the possibility that its value may be enhanced if it is linked to a system of appeal.

The choices before us are simple. One alternative is to have no appeals at all – in the sense of review of the merits. … Another is that we have the present unregulated and haphazard system – which is developing empirically without any real planning and may not be entirely satisfactory. The third is that we go the whole way and try to establish a proper appeals arrangement. But if we are to do that, how is it to be structured? The solution to this last question is so fraught with difficulties that we may find that, despite its idealistic appeal, it is not a practical alternative."40

An appellate body to review investment treaty decisions would provide the perception of consistency and predictability which would in turn assist in legitimising and institutionalising investor-state dispute settlement, making the system more sustainable.

The latest US Free Trade Agreements and the new US Model BIT address the possibility of the establishment of such an appellate body as follows:

"If a separate multilateral agreement enters into force… that established an appellate body for purposes of reviewing awards rendered by tribunals constituted pursuant to international trade or investment agreements to hear investment disputes, the Parties shall strive to reach an agreement that would have such appellate body review awards rendered… in arbitrations commenced after the appellate body’s establishment."41

On 15th October 2004 ICSID released a "Discussion Paper About Possible Improvements to the Framework for ICSID Arbitration". This raised for discussion the prospect of a single appeal mechanism, as an alternative to multiple appellate mechanisms arising from different appellate mechanisms under a number of investment treaties. The proposal was that ICSID would pursue an Appeals Facility on the basis that this would operate as a single appellate mechanism.

The features of such an ICSID Appeals Facility (set out in an Annex to the Discussion Paper) would include a set of Appeals Facility Rules adopted by the ICSID Administrative Council, such that no treaty amendments would be required, for use in conjunction with ICSID cases, ICSID Additional Facility cases and ad hoc UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules cases. Availability of the Appeals Facility would depend upon the consent of the parties to the dispute. The Appeals Facility Rules would provide for the establishment of an appeals tribunal of 15 persons selected by the ICSID Administrative Council upon nomination by the ICSID Secretary General. Appeals would be heard by a three-member appeals tribunal appointed by the Secretary General after consultation with the parties.

Grounds for an appeal would be the existing five grounds for annulment of an ICSID Award under Article 52 of the Convention, clear error of law or serious errors of fact (narrowly defined to preserve deference to findings of facts of the arbitral tribunal). The Appeal Tribunal would have the power to uphold, modify, reverse or annul the award. If the award was annulled, modified or reversed either party could submit the case to a new arbitral tribunal.

However, in a second Discussion Paper on procedural reforms issued by ICSID on 2 June 2005 these proposals for an appeals facility have been shelved, having regard to feedback received from member-governments and others42, with the observation that if such an appeals facility is to be brought into being, ICSID would be its natural home.

E. Investment treaty arbitration and public interest

There are evident similarities between international commercial arbitration between private parties and investor-state arbitrations under investment treaties. These have been emphasised by the heavy involvement in the latter of counsel and arbitrators whose background and practice has been in private commercial arbitration. This has to some extent masked the differences. However, public interest and public policy issues that arise in investment treaty arbitrations have led to an increasing public awareness that such arbitrations are different in kind.

The nature of the issues that arise in investment treaty arbitrations have led to increasing calls for greater flexibility in the admission of submissions from interested third parties (amici curiae) as well as for access by the public to open hearings in appropriate cases.

In Methanex Corporation v. United State43, California banned a methanol-based gasoline additive and Methanex commenced arbitration under NAFTA Chapter 11 claiming the ban was an expropriation and in breach of national and international standards of treatment, seeking damages of U.S.$1 billion. The arbitration was held under UNCITRAL Arbitration Rules. Four NGO’s (U.S. and Canadian) sought to file amicus briefs. The U.S. supported amicus brief submissions whilst Methanex opposed them. The tribunal found that it had authority under UNCITRAL Rules 15 to accept amicus briefs and proceeded to do so. Amici (as well as the general public) were also permitted to watch the hearings on closed-circuit TV. A final award in favour of the US was issued in August 2005.

In Mondev International Ltd. v. United States44 a NAFTA tribunal concluded there was no confidentiality requirement under the ICSID Additional Facility Rules which prevented the U.S. (pursuant to a Freedom of Information Act request) from unilaterally releasing the contents of its communications regarding the arbitration.

However, in the ICSID case of Aguas del Tunori v. Bolivia45, referred to above Aguas, a majority-owned Dutch subsidiary of Bechtel, undertook to develop a water supply system in exchange for a 40-year concession on water-selling privileges. Widespread public protests against rate increases lead to their suspension. Aguas sought $25 million expropriation damages in ICSID arbitration under the Bolivia-Netherlands BIT. Aguas opposed the submission of amicus briefs by more than 300 health & safety groups, environmental organisations, community organisations and individuals. The tribunal held that in the absence of consent non-parties would not be permitted to participate. Amici would not be permitted to attend hearings unless both parties consented.

The recent ICSID Discussion Paper has also raised for discussion proposals for permitting tribunals to open hearings to additional categories of persons or to the public, subject to conditions prescribed by the tribunal and after considering the views of the parties and the Secretariat, but without giving a veto over open hearings to either party. The Discussion Paper also included proposals for giving ICSID tribunals authority to accept and consider submissions from third parties (amici curiae), subject to conditions that might include financial and other disclosures.

In addition, the Discussion Paper contained proposals to facilitate prompt publication of awards by making it mandatory for ICSID to publish extracts of awards.

A well-publicised illustration of the sensitive issues of national and public concern that may arise in investment treaty arbitrations is provided by the recent NAFTA arbitration of Loewen Group Inc. and Ray Loewen v. United States.46 This was the first case lodged against the United States under NAFTA. The Loewen Group ("LGI") was a Vancouver-based "death care" business that became one of the largest funeral home operators in North America. LGI bought a funeral home in Jackson, Mississippi that entered into funeral insurance contracts with O’Keefe, a local competitor. O’Keefe sued LGI in the Mississippi state court. During the jury trial O’Keefe’s lawyers used (in the words of the ICSID tribunal) xenophobic and racist invective against Loewen and LGI which the judge did nothing to prevent. The jury awarded damages against LGI in the amount of $500 million. The Mississippi appeals procedures required LGI to post a bond of 125% of the verdict appealed against as a condition of a stay of execution, pending the appeal. LGI was unable to raise this amount. As O’Keefe threatened immediate seizure of their assets LGI paid O’Keefe $170 million to settle the claim.

LGI and Loewen filed an investment arbitration against the U.S. under Chapter XI of NAFTA under the ICSID Additional Facility Rules. The tribunal comprised a former Australian Supreme Court Chief Justice (as chairman), a University of Chicago law professor and Yves Fortier, a prominent Canadian arbitration practitioner. Before the hearing Fortier withdrew, due to a potential conflict, and was replaced by Lord Mustill, a retired English Law Lord.

The tribunal held that a court judgment can be considered a governmental "measure" giving rise to liability for discrimination, failure to grant "fair and equitable treatment" and expropriation without adequate compensation. The arbitrators held that the combination of anti-Canadian rhetoric, arbitrary court procedures, the excessiveness of the jury verdict and the effective lack of a right of appeal combined to constitute a "denial of justice" and a breach of the NAFTA obligation to provide qualifying investors with fair and equitable treatment.

However (and to the surprise of some commentators), the tribunal dismissed the case on two grounds.

Firstly, LGI had not sufficiently exhausted available local remedies, as required under NAFTA:

"Too great a readiness to step from outside into the domestic arena, attributing the shape of an international wrong to what is really a local error (however serious) will damage both the integrity of the domestic judicial system and the viability of NAFTA itself ..".

Secondly, due to a bankruptcy reorganisation LGI had lost the requisite Canadian nationality and the tribunal held that it no longer had jurisdiction to decide the case under NAFTA. There is some question whether there is such a "continuing nationality" requirement under public international law, requiring the claimant to have the requisite nationality up to the time of the award. It is generally considered sufficient to have the requisite nationality at the time the claim arose and at the time the claim was brought.

In addition, LGI had also failed to establish discrimination because it been unable to identify an American investor in "like circumstances".

In October 2005 the Colombia US District Court rejected an application by Mr. Loewen to vacate the award, on the basis that the application was time-barred, and that the award had dispensed with the NAFTA Chapter 11 claims of both the Loewen Group and Loewen himself.

The United States-Australia Free Trade Agreement was the first post-NAFTA Free Trade Agreement the U.S. was scheduled to sign with another capital-exporting state. The final text was signed on 8th February 2004 without any provision on investor-state arbitration.

Recent Free Trade Agreements (FTA’s) that the U.S. has signed with capital-importing countries do not include investment chapters or investor-state dispute resolution based upon NAFTA. Both the U.S.-Chile and U.S.-Singapore FTA’s add language to the "fair and equitable treatment" standard to the effect that it (merely) "prescribes the customary international law minimum standard of treatment of aliens as the minimum standard of treatment to be afforded to covered investments". This has been described by some commentators as a regressive retreat by the US to bare minimum standards of investment protection.

The Central American Free Trade Agreement (signed by the parties in August 2004) includes a footnote to the article dealing with most-favoured-nation (MFN) treatment:

"The Parties note the recent decision of the Arbitral Tribunal in Maffezin47 The Parties share the understanding and intent that this clause does not encompass international dispute resolution mechanisms such as those contained in Section C of this Chapter, and therefore could not reasonably lead to a conclusion similar to that of the Maffezini case".

This issue once again illustrates the potential for apparently conflicting decisions as between ICSID different tribunals. In Maffezini the tribunal found that an unusually broad MFN clause in the Argentina-Spain BIT encompassed international dispute resolution procedures found in another BIT with Argentina. This suggested that an MFN clause could be applied to procedural as well as to substantive rights under the investment48 treaty. Similarly, in a jurisdictional decision rendered in June 2005 in Gas Natural v Argentina an ICSID tribunal ruled that the MFN clause in the Spain-Argentina BIT entitled the investor to invoke the more favourable dispute resolution provisions found in the investment treaty between the US and Argentina. The investor was thereby entitled to ignore the requirement in the Spain-Argentina BIT to have recourse to the local courts for a period of 18 months before resorting to international arbitration. The tribunal seems to have treated access to arbitration as part of the substantive rights offered under the BIT, and rejected Argentina’s contention that the MFN clause did not extent to "procedural" matters. However, the tribunal made no reference to the earlier ICSID decision in Plama Consortium Limited v Bulgaria49 in which that ICSID tribunal held that the MFN clause did not incorporate by reference dispute settlement provisions set-forth in another treaty. That tribunal ruled that the MFN clause did not apply to procedural matters because there was no express indication to that effect in the relevant treaty.

Similar limitations have been included in the most recent draft of the U.S.’s new Model Bilateral Investment Treaty.

These developments reflect a growing disquiet amongst US policy makers concerning some of the unintended consequences of the existing investment treaty regime:

"Many business and political leaders [in the United States] still support arbitration as the preferred method to resolve disputes between host countries and foreign investors. However … the United States [is now] pursuing a course and a tone quite different from when negotiating NAFTA. Moreover, vocal opposition to investment arbitration has been expressed by important segments of the media and several non-governmental organisations … after claims for unfair treatment were filed against the United States government, arbitration looked different than when American companies were the investors."50

Footnotes

1 Peru alone has concluded more than 400 such agreements between 1993 and 2004.

2 See details of this trend for OECD countries at http://www.oecd.org/dataoecd/13/62/35032229.pdf

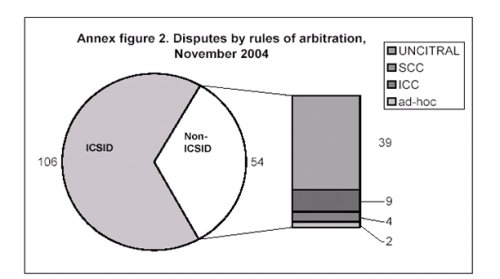

3 UN Conference on Trade Development: Trade and Development Board Commission on Investment, Ninth Session 7-11 March 2005; see Annexes 1-3 below.

4 As of March 2005 some 37 claims had been lodged against Argentina alone, 34 of which related to the Argentine 2001 financial crisis. In 2003 some 20 multi-national corporations filed claims against Argentina alleging violations of investment treaty guarantees in a variety of industry sectors including oil and gas production, telecoms, electricity and water distribution.

5 Currently, 51states and the European Communities have ratified the ECT.

6 Nykomb v Latvia

7 AES v Hungary ICSID Case No. ARB/01/4 resulted in a settlement; Plama v Bulgaria and others Case No. ARB/03/24 is currently before ICSID.

8 Pakistan/Germany

9 Framatone v. Atomic Energy Organisation (Iran).

10 Benteler v. Etat Belge ad hoc award 18th November 1983.

11 SPP v. Egypt ICSID (1984).

12 E.g. the Rumania - Sri Lanka BIT 1981 which provides ".. each Contracting Party hereby requires the exhaustion of local administrative or judicial remedies as a condition of its consent to conciliation or arbitration by the Centre."

13 Mobil Oil Nz Ltd v. Attorney-General [1989] 2 NZLR 649; 4 ICSID Reports 117 in which the New Zealand courts observed that ICSID arbitration constituted a self-contained machinery functioning in total independence from domestic legal systems.

14 English Commercial Court, Case No: 2004 FOLIO 656, judgement given on 29 April 2005, per Aikens, J.

15 ICSID Case No. ARB/81/1.

16 Award 1 September 2000 17 ICSID Rev-FILJ 382 (2003).

17 E.g. CMS Gas Transmission Company v. Argentina 17 July 2003 42 ILM 788 (2003).

18 ICSID Case No. ARB/96/3.

19 Mihaly International Corporation v Sri Lanka ICSID Case No. ARB/00/2.

20 Award, 15 November 2004

21 ICSID Case No. ARB/(AF)/))/3, 30 April 2004 (NAFTA)

22 Decision under ICSID Additional Facility, August 2000

23 E.g. the German Model Treaty Article 3 provides, "Measures that have to be taken for reason of public security and order, public health or morality shall not be deemed "treatment less favourable"".

24 Chapter IV

25 Decision on Jurisdiction 29 April 2004.

26 Professor Prosper Weil

27 ICSID Case No. ARB/02/3.

28 5 ICSID Rev. 367 (1998).

29 Compania de Aguas del Aconquija SA and Vivendi Universal v Argentine, Decision on Annulment July 2002.

30 Switzerland-Philippines BIT Article X(2).

31 6 August 2003 18 ICSID Rev. FILJ 301 (2003).

32 Decision on Jurisdiction 6 August 2003 18 ICSID Rev. FILJ 301 (2003).

33 Case RH 2003: 55; UNCITRAL Award September 2001.

34 ICSID case ARB/023/11 Award on Jurisdiction 6 August 2004.

35 Amco v. Indonesia Decision on Annulment 16 May 1986 1 ICSID Reports 509.

36 Iran-U.S. Claims Tribunal Case No. 56 (Chamber Three) Award No. 310-56-3 Partial Award, 14 July 1987 para. 18.

37Cremades & Cairns "Contract and Treaty Claims and Choice of Forum in Foreign Investment Disputes": "Arbitrating Foreign Investment Disputes: Procedural and Substantive Legal Aspects " (Kluwer 2004).

38 The problems of inconsistency faced in the CME/Lauder v. Czech Republic arbitrations could have been mitigated if the parties had been able to agree the proposal for consolidation.

39 Canfor Corporation, Tembec et al.

40 "Aspects of the Administration of International Justice", Elihu Lauterpacht.

41 Article 10.19.6 US-Chile FTA; Article 15.19.10 US-Singapore FTA; Article 28.10 new Draft US Model BIT.

42 See for example the submissions by the Geneva-based South Centre, reflecting feedback received from a grouping of developing countries, at

http://www.southcentre.org/. There report suggests that third party submissions tend to be hostile to developing countries, and that ICSID should take further steps to include developing countries in discussion of its reform proposals.43 30 December 2003.

44 ICSID Case No. ARB(AF)/99/2.

45 ICSID Case No. ARB/02/3.

46 ICSID Case No. ARB (AF)/98/3 Decision on Competence and Jurisdiction 5 January 2001.

47 ICSID Case No. ARB/97/7.

48 ICSID Case No. ARB/03/10 Decision of Tribunal on Preliminary Questions of Jurisdiction 17 June 2005.

49 ICSID Case No. ARB/03/24 Decision on Jurisdiction 8 February 2005.

50 Guillermo Aguilar Alvarez and William W. Park "The New Face of Investment Arbitration: NAFTA Chapter 11" 2004 Mealey’s International Arbitration Report (January).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.