- within Antitrust/Competition Law, Food, Drugs, Healthcare, Life Sciences and Transport topic(s)

A draft report adopted by JURI indicates the European Parliament may move to bring the financial sector within the scope of the Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD). Read about this and certain other proposed amendments to the CSDDD in this article.

On 23 February 2022, the European Commission (Commission) published its initial proposal (EC Proposal) for a Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive (CSDDD) requiring in-scope companies to conduct due diligence on, and take responsibility for, human rights abuses and environmental harm throughout their value chains. On 1 December 2022, the Council of the European Union (Council) adopted its position (Council Position) on the proposed CSDDD. On 25 April 2023, the European Parliament's committee on legal affairs (better known as JURI) adopted a draft report (JURI Report) entailing a suite of amendments to the CSDDD as proposed by the Commission. The draft report as now adopted by JURI typically gives a good indication on the position the European Parliament may take. The final vote by the European Parliament is expected for June 2023, following which negotiations among the Commission, the Council and the European Parliament will take place towards a final text of the CSDDD. Once the CSDDD has been formally adopted - not expected before 2024 - EU Member States will have two years to implement the CSDDD into national legislation. In this article, we identify some expected key points for those negotiations.

In our previous ESG key legal considerations, we discussed the initial proposal for the CSDDD and the Council Position. For more information about the CSDDD, we refer to the special issue of Tijdschrift Ondernemingsrecht (free access here), which contains a contribution of our colleagues Kitty Lieverse and Menno Baks.

1. Will there be a CSDDD?

The answer to this question seems to be is a firm "Yes". Although the Council Position and the JURI Report clearly indicate that important elements of the CSDDD as proposed by the Commission will be subject to debate, it is equally clear that there is sufficient support for a CSDDD, in some shape or form, throughout the EU legislative bodies as well as EU Member States. The question is, therefore, not whether there will be a CSDDD, but rather what obligations it will impose, to whom it will apply and how compliance with the CSDDD will be supervised and enforced.

2. Expected key negotiation points towards a final text

2.1 Scope

Threshold criteria

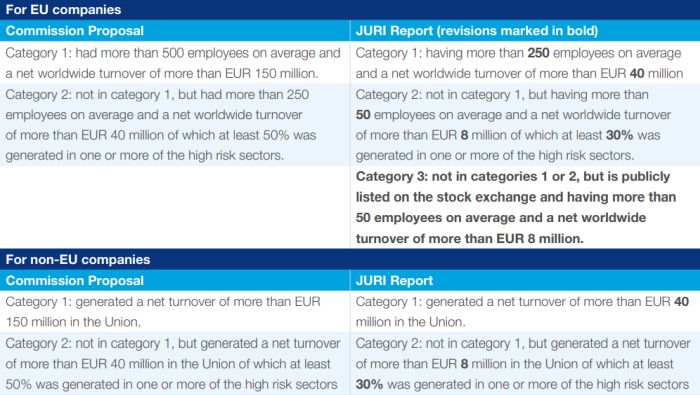

The initial proposal for the CSDDD already provided for certain

large companies both formed within and outside of the EU to be

subject of the CSDDD. This concept (including the extraterritorial

effect), seems to have been accepted by both the Council and JURI.

However, it seems that there will be some debate to be held about

the threshold criteria companies need to meet in order to qualify

as 'large' under the CSDDD because JURI seems to push for

significantly lower threshold criteria compared to the EC Proposal

as illustrated in the table below.

Threshold criteria (summarised)

Although the Council seems to be in principle fine with the threshold values initially proposed by the Commission, the Council Position adds a requirement to meet the relevant thresholds for at least two consecutive financial years. Furthermore, the Council Position includes an additional layer of 'very large' companies in respect of the staggered phase-in of the CSDDD. Under the Council Position, the obligations under the CSDDD should first - within three years from entry into force of the CSDDD - apply to companies with more than 1,000 employees and a worldwide net turnover of EUR 300 million (or non-EU companies with EUR 300 million turnover in the EU). Finally, although it can be derived from the initial proposal by the Commission, the Council Position also clarifies that the threshold criteria need to be assessed on a standalone basis (as opposed to on a consolidated basis).

The classification of a company in either category 1 or category 2 is relevant in that certain obligations under the CSDDD - most notably the obligation to adopt a plan to ensure that the business model and strategy of the company are compatible with the transition to a sustainable economy and with limiting global warming to 1.5°C, in accordance with the Paris climate agreement (Article 15 of the EC Proposal) - will only apply to companies falling in category 1.

Applicability to the financial sector

Another key outstanding item, seems to be about the question

whether the financial sector should be (substantially) excluded

from the CSDDD. Although not entirely clear, the initial proposal

by the Commission seems to bring most of the actors in the

financial sector (such as banks, insurers and investment funds)

within the scope of the CSDDD, provided they meet the threshold

criteria discussed above. In the Council Position, it is left up to

each Member State to decide whether or not bring the financial

sector within the scope of the CSDDD, and if brought into scope,

the 'chain of activities' would be limited to services that

directly result in an allocation of capital or in the coverage of

risk through insurance or reinsurance. The JURI Report takes an

opposite position and clearly brings the financial sector within

the scope of the CSDDD. JURI even marks the provision of financial

services as a high risk sector, thereby making it also relevant for

the assessment for category 2 classification as described above and

such widening the potential applicability of the CSDDD to the

financial sector. If the European Parliament indeed adopts this as

its formal position, the CSDDD's applicability to (large)

banks, insurers, investment firms, investment funds and other

actors within the financial sector will certainly be one of the key

negotiation points.

2.2 "Value chain" vs "Supply chain"

The companies in scope of the CSDDD will be required to conduct human rights and environmental due diligence by carrying out the following actions, in line with prior OECD Guidance for Responsible Business Conduct:

- integrating due diligence into their policies (Article 5);

- identifying actual or potential adverse impacts (Article 6);

- preventing and mitigating potential adverse impacts, and bringing actual adverse impacts to an end and minimising their extent (Articles 7 and 8);

- establishing and maintaining a complaints procedure (Article 9);

- monitoring the effectiveness of their due diligence policy and measures (Article 10); and

- publicly communicating on the description of due diligence, potential and actual adverse impacts and actions taken on those (Article 11).

Under the initial proposal of the CSDDD, the due diligence obligations do not just pertain to the company itself, but also to its subsidiaries and their operations, as well as operations carried out in the value chain by established business relationships. In the Council Position, the term "value chain" is replaced by "chain of activities" and defined such that it reflects a shift to a supply chain focus rather than the entire value chain. As a result, under the Council Position the due diligence obligations no longer extend to the impact of a company's product by the disposal thereof by consumers. JURI seems to stick to the more fulsome scope of the initial proposal by the Commission.

2.3 Directors' duties

In its initial proposal for the CSDDD, the Commission introduced two articles regulating the directors' duties for EU companies. The first concerns a duty of care - and related liability - for directors, when fulfilling their duty to act in the best interests of the company, to take into account the impact of their decisions on sustainability issues, including, where applicable, the impact on human rights, climate change and the environment, including in the short, medium and long term. The second required EU Member States to ensure that directors of EU companies are responsible for putting in place and overseeing the due diligence actions and to take steps to adapt the corporate strategy to take into account the actual and potential adverse impacts identified pursuant to its obligations under the CSDDD.

In the Council Position both articles have been deleted. According to the Council, the main elements of the second provision have been moved into the requirement for companies to integrate due diligence into their policies. Although there indeed seems to be some overlap, it also seems that in respect of this second provision the Council Position introduces a lighter touch regime in respect of a company's strategy. JURI, on the other hand, proposes only some amendments which do not seem to change the substance of the initial proposal by the Commission. Therefore, the introduction of directors' duties appears to be another key point for negotiations.

2.4 Civil liability

The EC Proposal included a combination of administrative enforcement and civil liability to monitor and ensure overall compliance with the obligations set forth in the CSDDD. EU Member States are required to establish a civil liability regime for companies for damages suffered by victims due to a company's failure to exercise due diligence and take appropriate measures to end identified adverse impacts. EU Member States must ensure that the civil regime for the liability of companies has an overriding mandatory application, so that civil liability cannot be denied on the sole ground that the law applicable to such claims is not the law of an EU Member State. It should be noted that, assuming compliance with Articles 7 and 8 of the EC Proposal, a company shall not be liable for damages caused by an adverse impact arising as a result of the activities of an indirect established business relationship, unless it was unreasonable for the company to expect, in the specific circumstances of the case, that the actions taken in accordance with Articles 7 and 8 would be adequate to prevent, mitigate, bring to an end or minimise the extent of the adverse impact.

In the Council Position it is proposed to significantly amend the civil liability regime under the CSDDD such that civil liability effectively only arises when the non-compliance with the CSDDD amounts to a tortious act under the Member States' tort law systems, thereby significantly reducing the (potential) scope for civil liability and thus putting more emphasis on the administrative enforcement of the CSDDD. Also here, the JURI Report takes a different direction and actually seems to broaden the scope for civil liability for non-compliance with any of the obligations under the CSDDD (instead of just non-compliance with the obligations set out in Articles 7 and 8) if as a result a such non-compliance, the company (or a company under its control) caused or contributed to an adverse impact that should have been identified, prevented, mitigated, brought to an end, remedied or its extent minimised through the appropriate measures laid down in the CSDDD and led to damage.

3. Next steps

The first immediate next step is for the European Parliament to adopt its final mandate as regards the CSDDD. As mentioned, the final vote by the European Parliament is expected for June of this year. Thereafter, the negotiations among the Commission, the Council and the European Parliament will take place towards a final text of the CSDDD. Once the CSDDD has been formally adopted - not expected before 2024 - EU Member States will have two years to implement the CSDDD into national legislation.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.