- within Privacy, Antitrust/Competition Law and Family and Matrimonial topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy industries

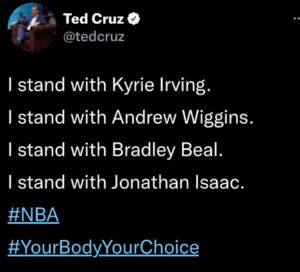

On September 26, 2021, the NBA denied Andrew Wiggins' religious accommodation request to be exempt from taking the COVID-19 vaccine. After being denied, Wiggins stated his "[b]ack is up against the wall, but I'm just going to keep fighting for what I believe. . . I'm going to keep fighting for what I believe is right. What's right to one person isn't right to the other person and vice versa." When pressed regarding what those actual beliefs entail, Wiggins responded, "It's none of your business, that's what it comes down to." See the story and some of Wiggins' quotes here. Wiggins eventually relented and got the vaccine. However, this incident started a storm of discussion from lawmakers regarding vaccine requirements. Senator Ted Cruz sent out a tweet stating:

The vaccine mandates in the NBA are similar to vaccine mandates by other employers, but, in response to any such mandates, under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended ("Title VII"), employees who have sincerely held religious beliefs against a vaccination may request an accommodation. This article explores the interactive process that an employer and employee must engage in to decide whether the employer can or has to offer an employee a religious exemption from a vaccine mandate and, if so, what the accommodation looks like. Many other materials on this issue discuss this in terms of a "religious exemption," but that is not accurate. The proper term is an accommodation that may, in some instances, include the employee being excused or otherwise exempted from the vaccine mandate, among other accommodation options, such as unpaid leave, continued facial coverings, etc.

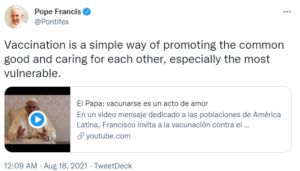

Courts limit certain types of inquiries employers can make from employees and are typically reluctant to scrutinize an individual's religious beliefs, not requiring that any belief in question be based upon an organized or recognized teaching of a particular sect. Even if formal religious affiliation were a requirement, the organized religions differ. For example, Pope Francis—the leader of the Catholic Church— tweeted the following support for COVID-19 vaccinations:

Additionally, leaders of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (also known as the Mormon Church) have urged members to get the vaccine. And although church-going Catholics were "accepting" of the vaccines, approximately 23% of Catholics are not accepting. Furthermore, about 15% of Latter-day Saints identified as vaccine-hesitant, with 19% saying they would not get the vaccine. With such back and forth amongst organized religions, it is easier to understand why employers cannot just simply determine what the religious doctrine is of a particular sect in deciding whether to grant or deny a religious accommodation for vaccines.

Although the Supreme Court has analyzed religious exemptions relating to military service, courts have applied the reasoning below to assess religious accommodations for employers:

Men may believe what they cannot prove. They may not be put to the proof of their religious doctrines or beliefs. Religious experiences which are as real as life to some may be incomprehensible to others. Local boards and courts in this sense are not free to reject beliefs because they consider them "incomprehensible." Their task is to decide whether the beliefs professed by a registrant are sincerely held and whether they are, in his own scheme of things, religious.1

Therefore, although Title VII broadly defines religious belief to include "all aspects of religious observance and practices," an employee's belief must be (1) religiously motivated and (2) sincerely held. The EEOC stated that if an employee claims that their belief is religiously motivated, the first part of the inquiry essentially ends, and an employer moves on to determine if the accommodation is based upon a "sincerely held belief." For example, if an employee merely requests a religious accommodation because they are scared of the vaccination and there is no religious motivation behind it, a religious accommodation is unnecessary. If the request is religiously motivated, then an employer needs to go to the next step of the analysis and determine if it is sincerely held.

The EEOC also has issued guidance on how to determine if an employee's religious belief is sincerely held. "If, however, an employee requests religious accommodation, and an employer has an objective basis for questioning either the religious nature or the sincerity of a particular belief, observance, or practice, the employer would be justified in seeking additional supporting information." The EEOC has stated that an EEOC investigator can look for the following documentation in determining whether a belief is sincerely held:

- Oral statements, an affidavit, or other documents from the charging party describing his or her beliefs and practices, including information regarding when the charging party embraced the belief, observance, or practice, as well as when, where, and how the charging party has adhered to the belief, observance, or practice.

- Oral statements, affidavits, or other documents from potential witnesses identified by the charging party or respondent as having knowledge of whether charging party adheres or does not adhere to the belief, observance, or practice at issue, fellow adherents, family, friends, neighbors, managers, or coworkers who may have observed his past adherence or lack thereof, or discussed it with him.

Accordingly, federal courts allow employers to make a "limited inquiry" regarding whether an employee's beliefs are "sincerely held."2

If an employee fails to cooperate with the limited inquiry, then an employer is likely able to deny an employee's request for a religious accommodation: "An employee who fails to cooperate with an employer's reasonable request for verification of the sincerity or religious nature of a professed belief risks losing any subsequent claim that the employer improperly denied an accommodation." However, if an employer unreasonably requests excessive corroborating evidence, employers run the risk of being held liable for discrimination or failing to accommodate. Therefore, an employer needs to only ask for what is necessary to determine whether a belief is sincerely held and not be too probing.

Finally, if an employer determines that an employee has a sincerely held religious belief, it does not necessitate that an employee can skip the vaccination and come to work. An employer still needs to determine whether or not they can provide reasonable accommodation to the employee. A reasonable accommodation does not mean providing the employee the accommodation the employee wants, as the employer must look at the issue on a case-by-case basis and determine what is reasonable under the circumstances. That case-by-case inquiry also takes into account the industry at issue, the employer's business, the employer's staffing, and productivity requirements, the employer's interface with the public, among many other factors. For some, reasonable accommodations can include any of the following:

- Required face coverings

- Social distancing

- Modified shifts

- Periodic testing

- Teleworking

- Reassignment

If an employee then states that face coverings are against their sincerely held religious beliefs, a federal court has already ruled a second religious accommodation is unnecessary.3 Additionally, no reasonable accommodation is necessary if it imposes an undue hardship. According to the Supreme Court, "an accommodation causes undue hardship whenever that accommodation results in more than a de minimis cost to the employer.4" For example, the NBA may have felt it was an undue hardship to have Wiggins play a physical sport in a closed arena, where players engage in aerobic activity for 48 minutes a game. Accordingly, when a religious accommodation is requested, employers may strike a balance and figure out what is best for the team based upon an individual's request.

Footnotes

1 United States v. Seeger, 380 U.S. 163, 184, 85 S.Ct. 850, 13 L.Ed.2d 733 (1965)(emphasis added)

2 Bushouse v. Local Union 2209, United Auto., Aerospace & Agric. Implement Workers of Am., 164 F. Supp. 2d 1066, 1077 (N.D. Ind. 2001). ("Thus, a limited inquiry into the sincerity of a union member's claimed religious beliefs allows the union to ascertain whether an individual is motivated by sincere religious convictions as opposed to political or other convictions which might be used by a member to avoid a particular union requirement.")

3 Klaassen v. Trustees of Indiana Univ., 1:21-CV-238 DRL, 2021 WL 3073926, at *39 (N.D. Ind. July 18, 2021)(examining a university's religious exemptions for vaccine mandates for the university's students)

4 Ansonia Bd. of Educ. v. Philbrook, 479 U.S. 60, 66, 107 S. Ct. 367, 371, 93 L. Ed. 2d 305 (1986)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.