The Grim Statistics on Mortgage Delinquencies and Foreclosures

As the financial crisis deepens, public attention is increasingly focused on the effect on millions of Americans who have lost (or are projected to lose) their homes, with many calling for government intervention. The statistics on foreclosures and the effect of the decline in housing prices on the equity of those homeowners are staggering.

The rapid depreciation in housing prices has already left millions of homeowners with negative equity on their houses. Those homeowners are "under water," with the unpaid balance on their loans exceeding the current market value of their homes, so they have little economic incentive to continue paying their mortgages. According to a recent report, as of the end of the third quarter of 2008, 18% of all properties with a mortgage had negative equity, and an additional 5% were approaching this threshold.1 The crisis has been felt most strongly in a small group of states. According to the report, the top six states in terms of percent of mortgages with negative equity —Nevada, Michigan, Florida, Arizona, California, and Georgia—account for over 58% of all negative equity mortgages, although they account for only 36% of all mortgages.2 The average percentage of mortgages with negative equity for these states is 29%, while the average in the remaining 44 states is 12%.

Some experts expect that housing prices will decline by another 10-15%, returning to their pre-bubble level and raising the total of mortgages with negative equity to 40% of all homes with mortgages.3 The mortgages of five million homeowners would then exceed the value of their homes by 30% or more.4 According to another estimate, the total amount of negative equity for all owneroccupied houses is $593 billion.5

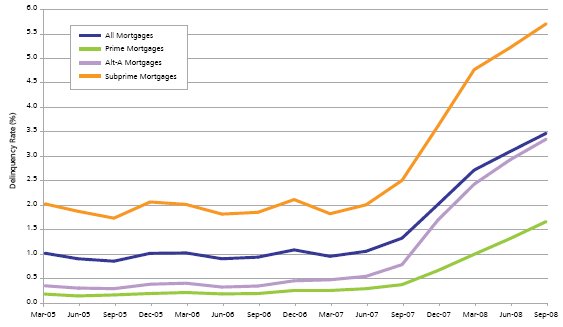

Another concerning measure is the rate of delinquencies. Delinquency rates, excluding foreclosures, have increased sharply since the third quarter of 2007 for all types of loans. The percentage of subprime mortgages 90 days or more past due has almost tripled during this period (from around 2% to almost 6%, see Figure 1).6

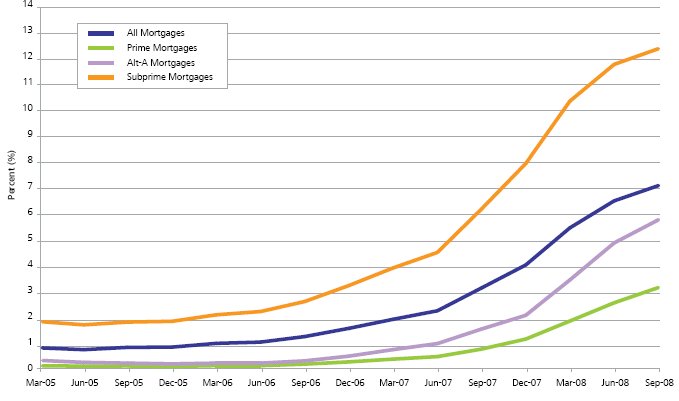

A similar trend is observed for foreclosures, with the rate for both prime and subprime borrowers increasing significantly, particularly since mid-2007. The foreclosure rate for subprime borrowers topped 12% in the third quarter of 2008, a three-fold increase since early 2007 (Figure 2). Combined with delinquencies, about 18% of subprime borrowers were either 90 days or more past due or were in foreclosure as of September 2008. According to a recent report by Credit Suisse, 3.5 million new foreclosures are expected in 2008-2009, and a total of 8.1 million households could fall into foreclosure by the end of 2012, representing about 16% of total households with mortgages.7

Figure 1: Delinquency Rates of US Residential Loans - Mortgages 90 Days or More Past Due

Notes and Sources:

Data are obtained from Mortgage Bankers Association through

Bloomberg, L.P.

Delinquency rate is seasonally adjusted and does not include loans

placed in foreclosure.

Figure 2: Foreclosures Inventory - US Residential Loans

Notes and Sources:

Data are obtained from Mortgage Bankers Association through

Bloomberg L.P.

The foreclosure inventory measure represents all loans in the

foreclosure process at the end of the reporting quarter. The data

are not seasonally adjusted.

The increasing rate of foreclosures imposes high costs and emotional distress on millions of American homeowners. Economic costs to a lender or investors in a mortgage-backed security on a loan that goes through foreclosure, measured by the loss due to foreclosure as a percent of outstanding balance, are estimated at about 32%, according to a recent paper by Campbell, et al.,8 and at a range of 30-40% according to another recent study by Alan White, which uses loan-level data on securitized subprime mortgages.9

With these statistics setting the tone for the public debate, many economists and regulators are calling for programs that target individual homeowners. Loss-mitigation techniques, such as repayment plans and loan modifications, have been used by lenders prior to the current crisis on a case-by-case basis in reaction to temporary hardship experienced by the borrower.10 While a modification typically requires the lender to defer the receipt of certain payments, or possibly accept a temporary or permanent reduction in payments, it may allow the lender to avoid the potentially high costs involved in exercising alternative recovery strategies, such as foreclosure. At the same time, the borrower can remain in his or her own home and avoid the monetary and psychological costs resulting from foreclosure and the need to relocate. The potential to modify a loan to the benefit of all parties is the main reason why many economists, regulators, and private lenders are focusing their efforts these days on designing and implementing large-scale loan-modification programs.

Multiple loan modification programs, chartered by government entities and private lenders, have been put in place over the past few months in response to the crisis. Loan modification programs operated by government entities include the IndyMac loan modification plan operated by the FDIC,11 and the Streamlined Modification Plan offered by the Federal Housing Financial Agency (FHFA), designed following the IndyMac model.12 In addition, the HOPE for Homeowners program, led by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA),13 is designed specifically to address borrowers with negative equity in their homes. Among the major private lenders who developed loan modification plans in response to the current crisis is Bank of America, with a plan arising out of its legal settlement regarding the mortgages it acquired through its acquisition of Countrywide,14 Citigroup,15 JP Morgan,16 HSBC,17 and GMAC.18

This article analyzes the economic incentives to the different parties—borrowers, lenders, servicers of mortgage portfolios, and investors in securitized mortgage pools—that can arise as a result of a loan modification program, and some of the complexities involved in the design of these programs.

Using Economic Theory to Understand the Complexities of Loan Modification Plans

Below, we discuss the economic incentives that are created by various aspects of loan modification plans, and the complexities that arise in designing programs in light of these incentives.

Complexity #1: The incentive to default to qualify

Eligibility for several existing loan modification plans requires borrowers to be at least 60 (or 90) days delinquent on their loans.19 Since loan modification plans provide substantial financial benefits to borrowers, on the margin, such requirements may create perverse incentives for borrowers who are current on their loans and can afford to continue making their payments, to default on their loans. Of course, the harm caused to a borrower's credit score from becoming delinquent and the associated ramifications should serve to balance the incentives to voluntarily default on a loan to qualify for a loan modification. However, according to officials at Fair Isaac, the company that markets the FICO credit score, the harm might not be sufficiently severe and, in any case, can be repaired over time by paying all credit accounts on time.20 As an additional safeguard to prevent fraud, almost all plans require that borrowers certify that they experienced hardship or change in financial circumstances, and did not purposely default to obtain a modification.

Some plans, such as the HOPE for Homeowners offered by the FHA, have taken a more direct approach, which is to avoid conditioning eligibility on being delinquent. For example, certain plans target both those currently delinquent and those estimated to be at high risk of default based on characteristics that are strongly correlated with the risk of default, such as high loan-to-value ratios, with special attention given to mortgage holders with "under water" loans, high loan-to-income ratios, or high overall household debt.21 A number of proposed plans, including a proposal by Professors Glenn Hubbard and Christopher Mayer from Columbia Business School,22 go one step further and propose to make the terms of the modified loans available to all existing homeowners, so that investors do not have an incentive to become delinquent on their loan or negatively affect their overall household debt or income in order to qualify for a modification.

Complexity #2: Moral hazard and adverse selection

The main goal identified by loan modification plans is to create affordable payments. Therefore, income, which is an observable, albeit potentially flawed, proxy of the borrower's ability to pay, is typically a key variable in determining the terms of the modified loan. Since a reduced income level implies improved terms, economists worry about the moral hazard problem that arises—presented with the option to modify their loans, borrowers have an incentive to understate their income. In response, most modification plans require some sort of hardship statement accompanied with some degree of documentation to support the borrower's inability to pay. However, the moral hazard problem is potentially deeper as the borrower has some control over the household's income level and can choose how much effort to exert to maintain or improve income. For example, the borrower can stop working overtime, or if both spouses work, one of them can quit their job, resulting in a verifiable decline in the ability to pay. Though not without cost, the borrower can presumably reverse the temporary decline in income after the loan is modified and the benefits are reaped. A related concern regarding the ability of the lender to observe the borrower's ability to pay is highlighted by Jaffee:23 "On home mortgages, in contrast [to commercial real estate], borrowers may substitute consumption for the mortgage payments, and it will be difficult for lenders to objectively identify those consumers for whom the loan payments are truly impossible."

Here, economists have argued that a potential fix is to create benefits for borrowers who can afford higher payments, for example by applying lower interest rates or charging lower mortgage insurance premiums in the modification for borrowers with lower loan-to-income ratios.

In addition, there are factors outside of the borrower's control that affect income and the risk of default such as current employment status and future income prospects or local housing market conditions. Often, the borrower would have better information about his "risk type" as measured by these factors than the lender does, giving rise to an adverse selection problem. Economic theory suggests that in the presence of adverse selection and moral hazard, efficiency may be improved by designing a loan modification program that offers a menu of options, each one catered to a different consumer type.24 Along these lines, the Hubbard and Mayer proposal for a loan modification program advocates implementing risk-based pricing, with interest rate based on the borrower's credit.25 Borrowers with the best credit, based on high FICO score and low loan-toincome ratio, will be entitled to the most favorable rate of 5.25%. In designing a loan modification plan, the benefits of such tailoring must be weighed against the simplicity and seeming fairness of a "one-plan-fits-all" approach.

Additional concerns arise for borrowers with negative equity in their homes. From an economic standpoint, these borrowers have an incentive to exercise the option to default on their loans and walk away from their homes. With more than 10 million homeowners now with mortgages that exceed the values of their homes and estimates that this number could double before housing prices decline to the pre-bubble level, this risk is severe.26 Many loan modification plans are designed to restore incentives in two ways: (1) writing off a portion of the outstanding balance of the loan, so that the modified balance no longer exceeds the current market value of the home; and (2) reducing payments to a level that is believed to be affordable. To provide the borrower with an incentive to exert effort to sustain income, as well as recoup some of the costs of the write-off to the lender (or to investors in the case of securitized mortgage pools), borrowers are also typically required to share current equity in their home (created as a result of the principal write-off), as well as future appreciation of their home at the time of future sale with the lender.27

Profit sharing arrangements in exchange for principal write-offs are a feature of the FHA HOPE for Homeowners program. Similarly, the Hubbard and Mayer proposal, as well as a proposal by two Yale professors (Jonathan Koppell and William Goetzmann28) involves refinancing troubled loans into new loans. The new loans would be issued by a government-sponsored corporation, analogous to the Homeowners' Loan Corporation (HOLC), with some of the new loans carrying lower principal balances in exchange for some form of profit sharing between the borrower, the current lender, and the government—who is the sponsor of the new loans. Another team of academics, led by Professor Andrew Caplin from New York University, supports the introduction of shared appreciation mortgage (SAM) into the market place, not just as a temporary solution to the current crisis, but as a permanent option. The basic concept is the same as discussed above: homeowners would be offered the chance to write down a portion of their mortgage debt in exchange for a share in future appreciation gains, resulting in reduced monthly payments and risk-sharing regarding future housing prices between the borrower and the lender.29 Caplin et al. note that incentives can be fine-tuned using profit sharing arrangements. For example, profit sharing can be designed to follow a schedule, with larger principal write-offs upfront requiring a higher share of future appreciation to be paid to the lender, providing the borrower an incentive not to understate their ability to pay in order to secure a larger write-off.30

They also note that with some profit sharing arrangements, the borrower may have an incentive to sell the home as quickly as possible, purchasing another home for which no profit sharing arrangement exists. In such a case, the borrower would benefit from the principal reduction that comes with the modified loan, but would limit the cost associated with foregoing a portion of future appreciation. To address this incentive, the percentage of profit sharing the lender is entitled to can be set to gradually decline over the life of the loan, presenting the homeowner with a disincentive to refinance as soon as prices create positive equity in the home.31

Complexity #3: The risk of redefault on modified loans

A major challenge of any loan modification plan is to identify mortgages that are sensible for the lender to modify, rather than ones likely to end in foreclosure even with modification. This problem is exacerbated in an environment with declining housing prices and deteriorating home equity, which creates additional incentives for borrowers to default on the loans.

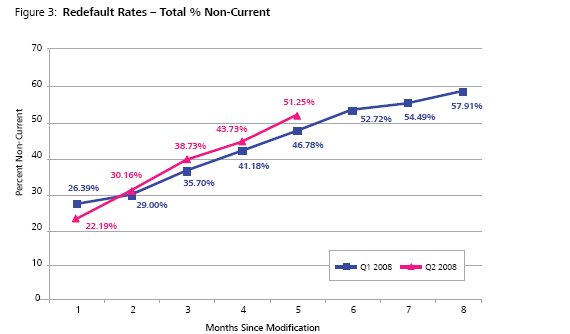

The concerns about redefault are frequently supported by statistics examining recent history. For example, the Office of the Comptroller of the Currency (OTC) and the Office of Thrift Supervision (OTS) reported that, of the loans modified in the first and second quarters of 2008, after three months, 36-39% of the borrowers had redefaulted by being more than 30 days past due. After six months, the rate was 51-53%, climbing to nearly 58% after eight months (Figure 3).32

A recent academic study identified the following groups of borrowers to be at high risk to redefault on a modified plan33:

- Borrowers with no equity in their home, since decreasing home values may lead them to default notwithstanding the level of their loan payment, unless the modified plan creates equity through a principal write-off

- Borrowers with mortgages already involving interest-only payments or certain minimum payment options, since rate reductions and re-amortization are unlikely to create affordable payments for them34

Notes and Sources

Overall Redefault Rates are from the OCC & OTS Mortgage

Metrics as of December 2008

The original chart can be found at

http://www.occ.gov/ftp/release/2008-142b.pdf

The public debate as to whether and to what extent the government should sponsor loan modification programs revolves around the cost and effectiveness of the modifications. Under the FDIC's proposal for a nationwide loan modification plan, modeled after the FDIC IndyMac program, the government will guarantee up to 50% of the loss on a modified loan to the lender or investors (in the case of securitized loans), as long as the modified loan does not redefault within the first 6 months.35, 36 Economic theory suggests that incentive may be further improved by applying a progressive schedule with the percent of government guarantee being dependent on how long the loan remains performing.37

Complexity #4: Potential conflicts of interest between servicers of mortgage-backed securities and investors in these securities

A large share of US mortgage debt, approximately 60% according to some estimates,38 is traded in mortgage-backed securities (MBS). The securitization process involves packaging pools of mortgage loans with similar characteristics into bonds that are subsequently sold to investors. The lender, who is the originator of the loans, sells all of its legal rights to receive payment on the mortgages to a trust. The trust then underwrites securities that are sold to investors. The servicer is the entity that processes the cash stream from borrowers and channels it to investors in exchange for a fee. In the event that the loan becomes delinquent, the servicer is also responsible for pursuing loss mitigation strategies, subject to the Pooling and Servicing Agreement (PSA). Because of the separation between the owners of the loan (investors) and the servicer, who is handling delinquent loans, conflicts of interest and other complexities arise for securitized loans. In recent testimony before the House Committee on Financial Services, Professor Christopher Mayer highlighted the need to augment loan modification efforts by addressing the specific issues arising for private-label securitized loans serviced by a third-party, especially as it seems that their percentage of recent foreclosures is substantially higher than their percentage of overall outstanding mortgages.39

The main revenue source for servicers is a fee that equals a fixed percentage of the outstanding balance of a loan while it is performing. Therefore, the servicer, in alignment with investors, would like to return a loan to a performing status. However, it is common that servicing contracts do not compensate servicers for costs involved with modifying a loan, a process that is typically time consuming and labor intensive, while they may compensate the servicer for costs associated with foreclosing a home. This could create an incentive for the servicer to pursue foreclosure, as opposed to loan modification, even at times when modification is more beneficial economically to both investors and the borrower. To attempt to address these potential conflicts, some economists have suggested embedding the following features in loan modification plans:40

- Paying servicers a fee for all "approved and properly executed" modifications, including out-ofpocket expenses and other overhead and labor expenses. For example, a recent proposal by Columbia University Professors Mayer, Morrison, and Piskorski advocates that servicers be paid a monthly Incentive Fee equal to 10 percent of all mortgage payments made by borrowers, subject to a cap per mortgage per month. Under this proposal, the servicer would also receive a one-time payment equal to 12 times the previous month's Incentive Fee if the borrower prepays the mortgages, rewarding servicers that accept short sales.41

- Setting clear guidelines for determining which loans to modify. PSAs govern servicers' duties and obligations to the investors of private label MBS. While PSAs typically state that a servicer has to "maximize the investors' interests," they are often unspecific. When considering whether to modify a loan, servicers often attempt to satisfy this obligation by a net present value (NPV) test comparing the payment stream from the modified loan with the alternative of foreclosure. While there is considerable discretion in performing the test by the choice of parameters (including the foreclosure discount and redefault rate assumed), a plan that uses a transparent procedure allows investors to monitor and evaluate the test.42

Other commentators have noted that another obstacle to loan modification plans for privatelabel securitized loans results from either limited (or no) authority to the servicer to modify loans under the current PSA or, in the presence of such authority, a litigation risk. They hypothesize that litigation risk has likely contributed to the growing gap between loan modification efforts exerted by the GSEs, major private banks, and portfolio lenders, and that of servicers of securitized mortgages. Some economists recognize the current situation, where servicers' ability to modify loans on behalf of their investors is limited, as a market failure that justifies government initiatives to resolve the issue.43 A proposal by Professors Mayer, Morrison, and Piskorski calls for a temporary legislation to eliminate legal barriers to loan modification in PSAs for all securitized loans. Their proposal advocates the elimination of outright prohibitions and provisions that constrain the range of permissible modifications, as well as a "litigation safe harbor" that would insulate servicers from litigation, provided they modified loans in a reasonable, good faith belief that they were acting in the best interest of investors as a group.44

A recent proposal from John Geanakopolos, Yale University professor of economics, and Susan Koniak, a former law professor at Boston University, advocates enacting legislation that would remove the modification function from the "master servicers," servicers of pools of loans, and transfer it to community-based, government-appointed trustees.45 These trustees would then examine individual loans and make a determination whether the loan should be left unchanged, modified, or moved to foreclosure, without being constrained by any existing servicing contracts for these loans. The proposed review process would be blind, meaning the trustees would have no information as to which securities are affected by the modification or foreclosure decision for a particular loan. The authors believe that, in addition to the direct benefits from facilitating the loan modification process, the review process would clarify the true value of individual loans, enhancing the market's ability to value the securities associated with those loans and assisting in regaining confidence to trade in those securities.

Complexity #5: The reputational effect for lenders and servicers

Lenders and servicers have traditionally been reluctant to modify loan terms, in part due to a concern that a demonstrated willingness to renegotiate in any given circumstance could affect their ability to stand firm with other current and future borrowers.46 In a paper published under the Commission on Growth and Development, Dwight M. Jaffee argues that the reputational concerns may be less pronounced in the current crisis as "lenders and servicers have been generally amenable to these government programs [e.g., FHA Secure], perhaps because the resulting loan modifications can be characterized as one-time emergency transactions." Notwithstanding, the expectation of a future government bailout can potentially create perverse incentives to both borrowers and lenders (or investors) to sit on the fence rather than expending effort to renegotiate loan modifications that are economically beneficial to both parties.

Some economists and commentators have voiced concerns that the negative effects of loan modification plans that bail out broad groups of borrowers outweigh the benefits, and that many of these plans are unfair in assisting borrowers who spent more than they could afford at the expense of those who were cautious and did not do so.47 Those objecting to an extensive bailout of troubled borrowers suggest, as viable alternatives, plans that limit the modification to targeted groups of borrowers, while assisting other borrowers in their transition to more affordable homes or to being renters in their own home.48 The basic premise of one such proposal, published by the Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee, is that homeowners with no equity in their homes are de facto renters. The proposal calls for the servicer (on behalf of the lender or investors) to accept a deed in lieu of foreclosure, and, in exchange, offer the borrower an affordable rental contract that would include an option to buy the home at a predetermined price, possibly lower than the unpaid amount of the loan, at some point in the future.49 This allows homeowners to remain in their homes while providing a cash flow to investors (rental income instead of mortgage payments) and avoids the costs associated with foreclosure. Furthermore, fewer foreclosed homes would enter the market, removing the downward pressure on home prices. The re-purchase clause encourages proper maintenance of the property, as the previous-homeowner now-turned-renter still has a potential stake in the home.

Conclusions

While there is wide agreement about the devastating economic consequences of the increasing rate of foreclosures on millions of Americans, there is no one agreed-upon remedy. On one end of the spectrum, there are those who advocate a massive government buyout of bad mortgages, with a plan to modify those mortgages so that payments are affordable and incentives to stay current on the loan are restored, with the government assuming the necessary loss and possibly taking a stake in the future appreciation of homes. On the other end stand those who are greatly concerned with the price tag of such intervention to American taxpayers, and who support only a minimal intervention by the government in the natural course of markets, for example in smoothing the transition from ownership to rental for the millions of homeowners who currently cannot afford their homes.

Modification of a mortgage may create a distortion of existing incentives to borrowers, lenders, servicers of mortgage pools, and investors in securitized loans. It is therefore important that any plan carefully accounts for newly-created incentives and complexities in its design.

NERA Economic Consulting (www.nera.com) is an international firm of economists who understand how markets work. We provide economic analysis and advice to corporations, governments, law firms, regulatory agencies, trade associations, and international agencies. Our global team of more than 600 professionals operates in over 20 offices across North America, Europe, and Asia Pacific.

* * * * * * * * *

NERA provides practical economic advice related to highly complex business and legal issues arising from competition, regulation, public policy, strategy, finance, and litigation. Founded in 1961 as National Economic Research Associates, our more than 45 years of experience creating strategies, studies, reports, expert testimony, and policy recommendations reflects our specialization in industrial and financial economics. Because of our commitment to deliver unbiased findings, we are widely recognized for our independence. Our clients come to us expecting integrity and the unvarnished truth.

End Notes

* The author thanks Elaine Buckberg, Denise Martin, Ron Miller, and Faten Sabry for helpful comments, and Stephen Budko for excellent research assistance.

1 See First American CoreLogic's Negative Equity Data Report (as of 30 September 2008) dated 29 October 2008, available at . In a recent speech, Ben Bernanke, Chairman of the Federal Reserve, estimated that "many borrowers find themselves 'under water' on their mortgages—perhaps as many as 15 to 20 percent by some estimates." See Ben Bernanke, "Housing, Mortgage Markets, and Foreclosures," Federal Reserve System Conference on Housing and Mortgage Markets, Washington, DC, 4 December 2008 available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/speech/bernanke20081204a.htm .

2 First American CoreLogic's Negative Equity Data Report, supra note 1.

3 Martin Feldstein, "The Problem is Still Falling House Prices, The bailout bill doesn't get at the root of the credit crunch," Wall Street Journal, 4 October 2008, available at http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122307486906203821.html?mod=googlenews_wsj . According to a recent Credit Suisse report, 41% of borrowers of non-agency loans already have negative equity as of September 2008, with forecasted further price declines in the next two years estimated to push this percentage to over 60; "Foreclosure Update, over 8 million foreclosures expected," Fixed Income Research, Credit Suisse, 4 December 2008, available at http://www.chapa.org/pdf/ForeclosureUpdateCreditSuisse.pdf .

4 Feldstein (2008), supra note 3.

5 Glenn Hubbard and Christopher Mayer, "First, Let's Stabilize Home Prices," Wall Street Journal, 2 October 2008, available at .

6 These figures are consistent with the assessment of John Dugan, Comptroller of the Currency, whereby "credit quality continued to decline across the board, with delinquencies increasing for subprime, Alt-A, and prime mortgages – and the greatest increase in percentage terms was in prime mortgages." See Remarks by John C. Dugan Before the OTS 3rd Annual National Housing Forum, 8 December 2008, p. 2, available at http://www.occ.treas.gov/ftp/release/2008-142a.pdf .

7 Credit Suisse (2008), supra note 3. Estimates for subprime loans are of 1.7 million new foreclosures in 2008-2009, and a total of 2.9 million that could fall into foreclosure by the end of 2012, representing almost 59% of households with a subprime loan.

8 John Y. Campbell, Stefano Giglio, and Parag Pathak, "Forced Sales and House Prices," p. 2. Conference papers found at http://www.richmondfed.org/conferences_and_events/research/2008/housing_and_mortgage_markets.cfm .

9 Alan M. White, "Rewriting Contracts, Wholesale: Data on Voluntary Mortgage Modifications from 2007 and 2008 Remittance Report," forthcoming in Fordham Urban Law Journal (2008), p. 16, Figure 1. 10 Kit Ladwig, "Mortgages Without Tears," Thomson Financial Media – Collections and Credit Risk, 31 January 1997; Bill Steele, "Loan modification program helps avoid foreclosure," Chicago Sun-Times, 3 March 2002.

11 For details see "FDIC Announces Availability of IndyMac Loan Modification 'Mod in a Box' Road Map Now Available to Institutions," FDIC Release, 20 November 2008, available at http://www.fdic.gov/news/news/press/2008/pr08121.html ; Loan Modification Program Overview, available at http://www.fdic.gov/consumers/loans/loanmod/FDICLoanMod.pdf .

12 For details see Statement of FHFA Director James B. Lockhart, Federal Housing Finance Agency, News Release, 11 November 2008, available at http://www.fhfa.gov/webfiles/169/newFHFASTATEMENT111108.pdf ; "HOPE NOW Joins with Government to Create Streamlined Mortgage Modification Plan," HOPE NOW News Release, 11 November 2008, available at http://www.hopenow.com/upload/press_release/files/SMP%20Release%20Final.pdf .

13 For details see "Prepared Remarks of HUD Secretary Steve Preston at the National Press Club," US Department of Housing and Urban Development Release, 19 November 2008, available at http://www.hud.gov/news/speeches/2008-11-19.cfm ; "Bush Administration Announces Flexibility for "Hope for Homeowners" Program," HUD News Release, 19 November 2008, available at http://www.hud.gov/news/release.cfm?content=pr08-178.cfm .

14 Bank of America Press Release: "Bank of America Announces Nationwide Homeownership Retention Program for Countrywide Customers,"6 October 2008, available at http://newsroom.bankofamerica.com/index.php?s=press_releases&item=8272 .

15 Citigroup Press Release, "Citigroup Announces New Preemptive Initiatives to Help Homeowners Remain in Their Homes," 11 November 2008, available at http://www.citigroup.com/citi/press/2008/081111a.htm .

16 JP Morgan Press Release, 31 October 2008, available at http://investor.shareholder.com/JPMorganChase/press/releasedetail.cfm?ReleaseID=344473 "JPMorgan Expands Loan Modification Plan," New York Times, 1 November 2008, available here

17 "HSBC paves a pathway in deepening loan crisis," Wall Street Journal, 18 November 2008. The banks current efforts are to target certain customers before adjustable rates reset, in order to modify their loans into a fixed rate loan.

18 "ResCap Announces Support for Streamlined Mortgage Modification Plan," PR Newswire, 11 November 2008, available at http://media.gmacfs.com/index.php?s=43&item=287 .

19 This is the case for the FDIC IndyMac loan modification plan as well as the Streamlined Modification Plan offered by the FHFA.

20 "Is it dumb to pay your mortgage?" The San Francisco Chronicle, 16 November 2008. For additional articles on impaired credit as a deterrence see "Battle Lines Form Over Mortgage Plan," Wall Street Journal (12 December 2008), available at http://online.wsj.com/article/SB119696216000715924.html?mod=hps_us_whats_news ; "Home loan aid may add to foreclosures," Financial Times (18 November 2008), available at http://www.ft.com/cms/s/0/b1aaba34-b5d9-11dd-ab71-0000779fd18c.html ; "Loan fixes alone can't save housing industry," Dallas Morning News (14 November 2008).

21 See Citigroup Press Release, "Citigroup Announces New Preemptive Initiatives to Help Homeowners Remain in Their Homes," 11 November 2008, available at http://www.citigroup.com/citi/press/2008/081111a.htm .

22 For details on the Hubbard and Mayer plan to stabilize the housing market see Testimony of Christopher J. Mayer Before the Committee on the Judiciary United States Senate Hearing: Helping Families Save Their Homes: The Role of Bankruptcy Law, 19 November 2008, available at http://judiciary.senate.gov/hearings/testimony.cfm?id=3598&wit_id=7543 [hereinafter "Mayer Testimony (2008)]. The plan is also posted at http://www4.gsb.columbia.edu/realestate/research/mortgagemarket .

23 Dwight M. Jaffee, "The US Subprime Mortgage Crisis: Issues Raised and Lessons Learned," Commission on Growth and Development, Working Paper No. 28, 2008, p. 21, available at http://www.growthcommission.org/storage/cgdev/documents/gcwp028web.pdf .

24 The term for this is a separating equilibrium. Michael Rothschild and Joseph E. Stiglitz, "Equilibrium in Competitive Insurance Markets: An Essay on the Economics of Imperfect Information," Quarterly Journal of Economics (1976), pp. 629–50. A menu of options is seen frequently in the insurance industry, where, for example, the premium is dependent on the driver's age and driving record, and, in addition, the consumer can choose the level of deductible, with lower deductible typically entailing a higher premium.

25 Mayer Testimony (2008), supra note 22.

26 Martin Feldstein, "How to Help People Whose Home Values Are Underwater – The economic spiral will get worse unless we do something about negative equity," Wall Street Journal, 18 November 2008, available at http://www.nber.org/feldstein/wsj11182008.html .

27 For ease of presentation, throughout the discussion on profit sharing arrangements, we will use the term "lender" to refer to the lender itself in the case of portfolio loans, and, in the case of securitized mortgage pools, to the group of investors who each owns a stake in the pool as opposed to the originator or the servicer. In Section D we discuss issues related to the authority of the servicer of securitized loan pools to perform modifications, including principal write-offs, on behalf of the investors.

28 Jonathan G.S. Koppell and William N. Goetzmann, "The Trickle-Up Bailout," The Washington Post, 1 October 2008, available at http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2008/09/30/AR2008093002316.html .

29 Andrew Caplin, Thomas Cooley, Noel Cunningham, and Mitchell Engler, "We Can Keep People in Their Homes, Let lenders profit later for easing terms now," The Wall Street Journal, 29 October 2008, available at http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122523972217878309.html .

30 See, for example, Andrew Caplin, Noel Cunningham, Mitchell Engler, and Frederick Pollock, "Facilitating Shared Appreciation Mortgages to Prevent Housing Crashes and Affordability Crises," The Hamilton Project, Discussion Paper 2008-12, The Brookings Institution, available at http://www.brookings.edu/papers/2008/09_mortgages_caplin.aspx .

31 Ibid., p. 9.

32 See Remarks by John C. Dugan Before the OTS 3rd Annual Housing Forum, 8 December 2008. Chart available at http://www.occ.gov/ftp/release/2008-142b.pdf .

33 Joseph R. Mason, "Mortgage Loan Modification: Promises and Pitfalls," 3 October 2007, available at http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1027470 .

34 Examples of mortgages with minimum payment options include payment-option ARM mortgages, which allow the borrower to make a minimum payment that can be lower than the interest accrued during the period. For more detail see http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/mortgage_interestonly/ .

35 See Testimony of Sheila C. Bair before the House Financial Services Committee, 18 November 2008, available at http://blogs.wsj.com/economics/2008/11/18/bairs-testimony-more-aggressive-intervention-is-needed/. Related materials can also be found at http://www.fdic.gov/consumers/loans/loanmod/ .

36 See Cheyenne Hopkins, "When Mods Fail, What Next? Regulators split on implication of redefaults," American Banker (9 December 2008). In the article, John Dugan also acknowledges that this means that a number of the redefaulting loans in the study would not have been sponsored by the government.

37 Some plans include incentives to servicers to modify loans, such as a fixed fee of $800 for each loan modification completed as offered under the FHFA Streamline Modification Plan. The same economic rationale that applies to guarantees suggests that a scheduled payment that depends on how long the modified loan remains performing may improve incentives to complete modifications that are more likely to survive.

38 Tomasz Piskorski, Amit Seru, and Vikrant Vig, "Securitization and Distressed Loan Renegotiation: Evidence from the Subprime Mortgage Crisis," available at .

39 Testimony of Dr. Christopher J. Mayer Before the House Committee on Financial Services Hearing: Priorities for the Next Administration: Use of TARP Funds Under EESA, 13 January 2009 [hereinafter, "Mayer Testimony (2009)"], available at http://www4.gsb.columbia.edu/realestate/research/housingcrisis/mortgagemarket.

40 Larry Cordell, Karen Dynan, Andreas Lehnert, Nellie Liand, and Eileen Mauskopf, "The Incentives of Mortgage Services: Myths and Realities," Finance and Economics Discussion Series Divisions of Research & Statistics and Monetary Affairs, Federal Reserve Board, Washington, DC, Working Paper 2008-46, p. 26, available at http://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2008/200846/200846pap.pdf .

41 Mayer Testimony (2009), p. 6, supra note 39.

42 The FDIC posts the spreadsheet used to calculate the NPV test on their website, along with the assumed inputs, thus making it transparent. See Net Present Value Worksheet at http://www.fdic.gov/consumers/loans/loanmod/loanmodguide.html .

43 See for example Oliver Hart and Luigi Zingales, "Economists Have Abandoned Principle," The Wall Street Journal, 3 December 2008, available at http://online.wsj.com/article/SB122826736608874577.html .

44 Mayer Testimony (2009), pp. 6-7, supra note 39.

45 John D. Geanakopolos and Susan P. Koniak, "Mortgage Justice Is Blind," New York Times, 30 October 2008, available at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/30/opinion/30geanakoplos.html .

46 Dwight M. Jaffee, "The US Subprime Mortgage Crisis: Issues Raised and Lessons Learned," Commission on Growth and Development, Working Paper No. 28, 2008, p. 4, available at http://www.growthcommission.org/storage/cgdev/documents/gcwp028web.pdf .

47 "Mortgage Plan May Aid Many and Irk Others," New York Times, 31 October 2008, earlier version available at http://www.nytimes.com/2008/10/31/business/31bailout.html?pagewanted=2&_r=1 .

48 See Charles Calomiris, Richard Herring, and Kenneth Scott, "Facilitating Mortgage Renegotiations: The Policy Issues," Statement of the Shadow Financial Regulatory Committee, 11 February 2008, available at http://www.aei.org/doclib/20080211_StatementNo.255.pdf ; and Daniel Alpert, "The Freedom Recovery Plan for Distressed Borrowers and Impaired Lenders," available at http://www.westwoodcapital.com/opinion/images/stories/articles_oct/the_freedom_recovery_plan.pdf . See section III for a detailed discussion of these proposals.

49 Charles Calomiris, Richard Herring, and Kenneth Scott (2008), supra note 48.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.