On 16 September 2015, the Court of Justice of the European Union (the "ECJ") ruled on a request for a preliminary ruling from the High Court of Justice of England & Wales, Chancery Division, Intellectual Property (Case C-215/14, Société des Produits Nestlé SA v Cadbury UK Ltd). In its judgment, the ECJ clarified some of the grounds for refusal or invalidity provided for in Article 3 of Directive 2008/95/EC of the European Parliament and the Council of 22 October 2008 to approximate the laws of the Member States relating to trade marks (the "Trade Marks Directive").

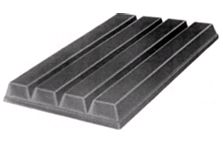

The case relates to the protection of the shape of the KitKat bar.

First, the ECJ focused on the absolute refusal grounds listed in Article 3(1)(e) of the Trade Marks Directive. These refusal grounds apply to specific signs consisting of the shape of the goods, namely the signs consisting exclusively of the shape which results from the nature of the goods themselves, of the shape of goods which is necessary to obtain a technical result, or of the shape which gives substantial value to the goods. The ECJ recalled that the absolute refusal grounds operate independently of one another and must therefore be applied independently. Therefore, if one of the criteria listed in Article 3(1)(e) is met, the sign which consists exclusively of the shape of the good must not be registered as a trade mark. Accordingly, the ECJ found that if the essential features of a sign fall under the scope of more than one ground of refusal, registration will be refused when at least one of these grounds fully applies to the sign at issue.

Second, the ECJ then assessed whether Article 3(1)(e)(ii) of the Trade Marks Directive refers both to the manner in which the goods at issue function as well as to the manner in which they are manufactured. To do so, the ECJ relied on the objective of the provision, i.e., preventing the grant of monopolies covering technical solutions which a user is likely to seek in the goods of competitors. Given that the manner in which the goods function is decisive from the consumer's perspective as opposed to their method of manufacture, the ECJ held that the provision must be interpreted as not applying to the manner in which the goods are manufactured. In doing so, the ECJ departed from the opinion of the Advocate General (See VBB on Business Law, Volume 2015, No. 6, p. 12 and 13, available at www.vbb.com).

Finally, the ECJ turned to the issue of acquired distinctiveness. The ECJ began its analysis by recalling that the essential function of a trade mark is to help identify the goods or services covered by that mark as originating from a particular undertaking, and thus to help distinguish the goods of the trade mark applicant from goods of other undertakings. Given that the distinctive character of a trade mark is acquired through use, the ECJ stressed the importance of that use causing the sign to identify, in the minds of the relevant class of persons, the goods to which it relates as originating from a particular undertaking. As a consequence, the ECJ concluded that the trade mark applicant must demonstrate that the relevant public recognises the origin of the goods or services on the basis of only the trade mark at issue, with the exclusion of any other trade mark which may also be present on the product.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.