- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

- in European Union

- in European Union

- in European Union

- in European Union

- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy and Pharmaceuticals & BioTech industries

Note from the Authors

When planning to outsource the production of a product, companies always aim to employ the best approach to meet their needs and demands. Contract manufacturing, both inside and outside the group, is a popular business model in the manufacturing sector often employed by multinational enterprises (MNEs) across the board in today's economy.

In this article, we will try to respond to the questions posed to provide the readers with insight on how the business model of contract manufacturing is treated by the Luxembourg Tax Administration (LTA). However, to be able to respond to the questions, we deem it appropriate to first provide a general background on contract and toll manufacturing.

i. Definition of contract manufacturing

Contract manufacturing is the process of contracting the entire production of a product or material to a third or related party, i.e., the manufacturer, which is responsible for selecting, procuring, and processing the raw materials to produce the final product according to the contracting party's or principal's specifications. The contract manufacturer uses a plant and equipment that it owns and takes title to raw materials and work in progress. However, it generally does not own or utilize any valuable intellectual property.

ii. Difference from toll manufacturing

While toll manufacturing is quite similar to contract manufacturing, there is one key distinction between the two. Contrary to the contract manufacturer which, as previously mentioned, is responsible for the entire production process from beginning to end, including the procurement of raw materials, the toll manufacturer is responsible only for the processing of raw materials or semi-finished products into finished goods, without being responsible for the sourcing of the materials.

In other words, in toll manufacturing, the principal supplies the toll manufacturer with the materials and product design and often also owns all the related intellectual property, such as patents and trademarks. The toll manufacturer in turn provides the plant, machinery, and labor force necessary to manufacture the specified product and is responsible only for transforming the raw materials or provided sub-assemblies into finished goods. The toll manufacturer bears none of the risks or costs associated with holding raw materials, work in progress, or inventory, and at no point in time does the toll manufacturer take ownership of the raw materials. Accordingly, as no transfer of legal title is involved, the toll manufacturer simply provides a manufacturing service to the principal, which instructs the toll manufacturer as to specifications, quality, and quantity requirements. This, in addition to not owning or utilizing any valuable intellectual property, results in the toll manufacturer performing a relatively routine function that is expected to be reflected in a lower profit.

The distinction between the two business models is not always straightforward and requires a careful review of the underlying contracts.

iii. Functions, assets and risks associated with contract and toll manufacturing

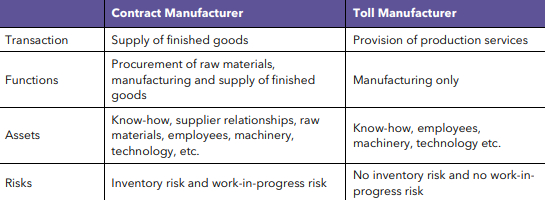

Based on the above, the following table summarizes the main differences in the functions performed, assets deployed, and risks assumed by the contract and toll manufacturers:

1. What kind of contract manufacturing operations do the tax authorities in your jurisdiction perceive as high risk, and how can MNEs safeguard their transfer pricing positions to mitigate such risks?

To date, the LTA has not published any guidance in relation to the benchmarking process for contract manufacturing intragroup transactions, and the Luxembourg courts have not ruled on any such cases. This absence of guidance both from the LTA and the Luxembourg courts could be attributed to the nature of the Luxembourg market, which is well known for its strong financial and banking industry, and less known for its manufacturing industry as compared to larger European jurisdictions.

As a general remark, experience shows that the LTA can challenge easier taxpayers' intercompany transactions when no transfer pricing (TP) documentation is prepared. In an environment where tax scrutiny is increasingly observed, taxpayers should make sure that all controlled transactions are duly documented and supported by TP documentation.

2. In your jurisdiction, what types of benchmarking studies (economic analyses) are accepted or typically applied when remunerating contract manufacturers?

a. Differences in the approach to benchmarking for contract manufacturers versus toll manufacturers;

The analysis of functions performed, assets used, and risks assumed by the parties to the relevant transaction is the cornerstone of every transfer pricing study. From the above high-level description of the contract and the toll manufacturer, the economic effect of both business models lies in the separation of the manufacturing function in the supply chain between the principal and the manufacturer, as well as the ownership of the raw materials used in the production process. It can therefore be argued that a contract manufacturer has more responsibilities and more risks than a toll manufacturer for benchmarking and comparability purposes.

The OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises and Tax Administrations (OECD Guidelines) state that where it is possible to locate comparable uncontrolled transactions, the comparable uncontrolled price (CUP) method is the most direct and reliable way to apply the arm's length principle and should therefore be preferred.1 Where the CUP method cannot be applied, the cost-plus method is usually applicable for both contract and toll manufacturers. This is also supported by the OECD Guidelines.2 Practitioners usually deploy a cost-based transactional net margin method (TNMM) when benchmarking both business models.

The cost base and the mark-up are expected, however, to be different in both cases. While the cost base in the case of a contract manufacturer generally includes all costs, including the costs of raw materials in the costs of goods sold, the cost base for a toll manufacturer typically includes all costs without the costs of the raw materials..

b. Adjustment for a contract manufacturer with capital intensive operations;

See response below.

c. Capacity utilization for the contract manufacturer and implications for transfer pricing;

As previously mentioned, contract manufacturers generally undertake more risks compared to toll manufacturers, namely inventory and work in progress risk. Although the manufacturer may be assured that its entire output will be purchased, assuming quality requirements are met,3 the risk that the goods might not be sold cannot be completely dismissed, for example, due to a defect. This, combined with fluctuations in the market, especially in instances of volatile markets, may lead to significant exposure for the manufacturer. The same could be argued in cases where the principal decides to increase the quantity needed for its operations, thus resulting in a deterioration of the manufacturer's position, which might no longer have the capacity to serve the principal.

In some cases, a higher remuneration might be appropriate. Following a close case-by-case review of the activities and risks of a contract manufacturer, adjustments might be appropriate to reflect the economic reality of the risks associated with this business model. Such adjustments might include adjustments related to inventory or cost of goods sold, or even adjustments made, or parameters used during the search for comparables through various software available on the market.

The OECD Guidelines state in that respect that, based on the specific details and context of the situation and specifically on the proportion of fixed and variable costs:

The TNMM may be more sensitive than the cost plus or resale price methods to differences in capacity utilization, because differences in the levels of absorption of indirect fixed costs (e.g. fixed manufacturing costs or fixed distribution costs) would affect the net profit indicator but may not affect the gross margin or gross mark-up on costs if not reflected in price differences.4

Absent any guidance both from the LTA and the Luxembourg courts in this respect, the OECD Guidelines should be followed.

3. What are the transfer pricing implications of government subsidies or grants in contract manufacturing?

a. Considerations involved in the decision to pass on the subsidies/grants to the principal or having them retained locally;

There is no stated policy from the Luxembourg tax authorities on how to deal with such subsidies. One may expect that where the subsidy is granted with the aim of expending manufacturing capacity locally, the subsidy would be allowed to be passed on in some form to the principal, as the principal makes decisions regarding the volume of the production from the contract manufacturer. More specific subsidies would not necessarily be expected to be passed on.

b. The effect of the subsidy on the cost base of the contract manufacturer on which a net cost plus is being applied;

Again, there are no guidelines from the Luxembourg tax authorities in this respect. If the cost-plus method is applied, and the subsidy is meant to stimulate production capacity of the contract manufacturer, one would expect the subsidy to lower the cost base on which the net cost-plus is being applied. For more specific subsidies, this should be less obvious.

c. Other issues pertaining to government subsidies or grants.

The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic led to restrictions on travel and social contact and created unprecedented disruptions to the global economy and supply chain. Many businesses, small and large, as well as individuals, relied on government subsidies, loans, suspension of payment of taxes, and other state support. As a result, there was a need to address how any government grants or subsidies should be treated for transfer pricing purposes.

As a response, on December 18, 2020, the OECD published its Guidance on the Transfer Pricing Implications of the COVID-19 Pandemic (the Guidance), which focuses on how the arm's length principle and the OECD Guidelines apply to issues that may arise in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Governments typically prefer that any assistance provided benefits their own citizens and businesses, rather than those in other countries. According to the Guidance:5

The potential effect of the receipt of government assistance on the pricing of a controlled transaction will depend on the economically relevant characteristics of the transaction, following an accurate delineation of the controlled transaction and the performance of a comparability analysis. Therefore, it would be contrary to the arm's length principle to assume that the mere receipt of government assistance would affect the price of the accurately delineated controlled transaction, without performing a careful comparability analysis (including an analysis of how the receipt of government assistance would affect the price of uncontrolled transactions, if at all, and the perspectives of both parties to the transaction).

There are instances in which a taxpayer would consider that an arm's length price must be adjusted to account for government interventions, such as regarding price controls (even price cuts), interest rate controls, subsidies to particular sectors, etc. In principle, these government interventions should be considered as circumstances of the market of a specific jurisdiction and should be accounted for in assessing the transfer prices in that jurisdiction.6

As third parties might not enter into a transaction that is subject to government interventions, it is uncertain how the arm's length principle should apply.7 Although there can be challenges in assessing the impact of a government policy in the determination of transfer prices, in principle, when government intervention equally affects transactions between both related and unrelated parties, the tax treatment for transactions between related enterprises should be the same as that for transactions between unrelated enterprises.8

Absent any specific guidance issued by the LTA and the Luxembourg courts in relation to contract manufacturing intragroup transactions, and the effect on government subsidies in the cost base of the contract manufacturer, the Guidance and the OECD Guidelines should be followed.

4. What are the transfer pricing considerations for financing expenses as they relate to transactions involving contract manufacturers and who should bear the foreign exchange risks in these transactions? Please explain your reasoning.

As in all transfer pricing studies, the key is the assessment of the parties through the analysis of functions, assets, and risks. Contract manufacturers usually perform relatively routine functions and, as a result, one would first have to make the assessment of whether the contract manufacturer can attract financing on its own or with the help of its principal.

When applying the cost-plus method, in both cases, one would expect the financing expense for funding obtained to finance manufacturing plants and the acquisition of raw materials to be part of the cost base on which a cost plus is applied.

As to foreign exchange risk, one would expect a contract manufacturer to obtain funding for plant and machinery to be in its local currency, or otherwise hedged to its local currency. Where borrowing in local currency leads to higher interest rates than borrowing in the currency that is most relevant for the principal, the principal would bear the higher costs through the inclusion of such funding costs in the cost base. If such funding is attracted with the assistance of the principal and such assistance comes in a currency other than the currency that the contract manufacturer is calculating its profits in, with the potential lower interest rates benefitting the principal through a lower cost base, the foreign exchange risk involved should be borne by the principal.

When it comes to the financing expense of raw materials, the currencies that apply to their purchase would be expected to match the currency of the price for the finished goods to be charged to the principal. Borrowings for such purchases expectedly are then also denominated in such currencies, so that currency exposure may be limited. If another currency is chosen, the question of who should bear the foreign exchange risk should depend on whether the choice for such other currency is on the initiative of the contract manufacturer or of the principal. In the latter case, the principal should bear the foreign exchange risk, but in the former case one would expect the contract manufacturer to bear the foreign exchange risk. In any case, allocation of such risk should follow a detailed functional analysis.

Footnotes

1 OECD Guidelines, paragraph 2.15, p.97.

2 OECD Guidelines, paragraph 7.40, p.325.

3 OECD Guidelines, paragraph 7.40, p.325.

4 OECD Guidelines, paragraph 2.76, p.117.

5 OECD Guidance, paragraph 79, p.21.

6 OECD Guidance, paragraph 1.152, p.78.

7 OECD Guidance, paragraph 1.156, p.80.

8 OECD Guidance, paragraph 1.154, p.79.

Originally published by Bloomberg Tax

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.