- within Technology topic(s)

- in Asia

- in Asia

- within Transport, Food, Drugs, Healthcare, Life Sciences, Government and Public Sector topic(s)

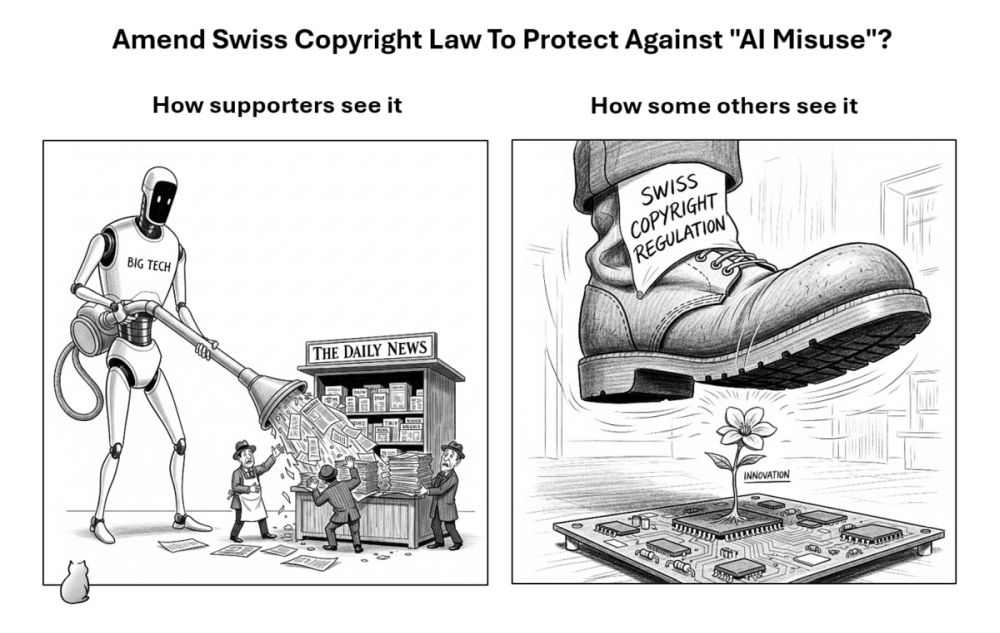

Media houses fear for their future, as AI providers like OpenAI, Perplexity, and Google use their content for their services and undermine their online traffic. A legislative proposal in the Swiss Federal Parliament aims to curb this perceived "abuse" by significantly tightening copyright law for AI, and it has already passed the first chamber. The motion is controversial. It seeks to extend copyright protection beyond the specific expression of a work to also cover the information it contains, and to eliminate existing copyright exemptions for AI providers. Critics warn this could lead to a de facto ban on many AI services in Switzerland, creating the world's strictest set of AI regulations. Proponents, however, argue the goal is not a ban but to gain bargaining power for fair remuneration for the use of their content. In part 28 of our blog series on AI, we use this example to illustrate the complexities of AI regulation and the risks of hastily applying existing legal concepts to aid few industries. Opinions are deeply and emotionally divided on whether this use of content even constitutes abuse. Consensual solutions, such as an opt-out right for rights holders or collective remuneration schemes, could offer a path forward without Switzerland scoring a regulatory own goal. We are venturing into this minefield to foster a deeper understanding of the issues and challenges, which extend far beyond Switzerland.

A supposed, a real and a desired problem

The starting point is not controversial in practice: after traditional media outlets came under increasing pressure from the business models of Google, Meta and Co. in the online advertising business and lost more and more advertising revenue to the latter (see analysis here), they are now also starting to suffer losses due to artificial intelligence. More specifically, there are two main problems:

- Problem No. 1: Many large language model (LLM)

providers have trained their models using a wide range of internet

content, including from Swiss media, thereby profiting from the

knowledge contained in these publications. However, this requires

differentiation. The proportion of Swiss media content in the

overall training data is vanishingly small. Furthermore, a study

with Swiss participation showed that content protected by a crawler

opt-out is largely irrelevant to an LLM's general knowledge

acquisition (see here; the situation is different in specialized

domains such as biomedical research when major publishers are

excluded). Conversely, it can be argued that such content does not

really contribute to the value creation of a language model, even

where content is protected by copyright. We mention this because

Swiss media regularly make use of such crawler opt-outs and, when

it comes to the core question of appropriate remuneration, such a

remuneration naturally depends on the economic contribution of a

particular content to end the result (more on this later). In any

event, under Swiss law, the use of such content for training

purposes is in principle legal, at least when publicly accessible

content is accessed and certain requirements are met, sometimes

even where there are crawler opt-outs (see here for details). Copyright issues can arise

in particular when language models reproduce protected content from

training verbatim (this is the subject of the New York Times'

most high-profile ongoing court case on the issue, see here), which AI model developers generally try

to prevent in various ways. Where an AI bot collects content from

the relevant website by circumventing a (technically effective)

paywall, for example by "hacking" it, legal action could

also be taken in principle: The "research exemption" of

Swiss copyright law (Art. 24d URG), which is frequently invoked for

AI training, only applies if there is "lawful" access to

the content. Even if such a lawful access were assumed only because

the AI bot uses a subscription but violates the agreed terms and

conditions (subscriptions regularly prohibit crawling), legal

action could be taken for breach of contract and, if necessary, for

violation of unfair competition law, even if copyright law did not

provide any recourse. Depending on the circumstances, this could

constitute the criminal offence of obtaining services by deception

or of unauthorised data collection. However, the actual enforcement

of these regulations is fraught with obstacles and therefore

sometimes impractical. At least, this is the view of the Swiss

media, which sees no recourse here. Whether access to content

behind the paywall as described actually occurs in Switzerland is

controversial. The Swiss media house Neue Zürcher Zeitung

(NZZ) claims that this happened with a text from their

"Einsiedler Anzeiger", while Zurich-based IT lawyer

Martin Steiger accuses the NZZ of fabricating "data

theft" by Perplexity AI (see here). In fact, the text in question (a

reader's comment) is briefly visible when visiting the website

and therefore accessible to the AI provider's bots, but it is

immediately covered so that human users can only read it with a

subscription. It is therefore debatable whether a paywall is

actually being circumvented here, or whether it has simply not been

implemented consistently enough to also force the AI provider's

bots to pay; in the case described, the bots will already have

"read" the article when the paywall appears. Of course,

there is additionally the possibility of circumventing paywalls

indirectly by collecting the content protected at the source and,

if necessary, piecing it together in other freely accessible

locations. In that case, the AI bot thus reconstructs the desired

article from quotations, excerpts or copies in third-party archives

(see here) and pieces it together (see here, which, as a point in case, is itself a

freely accessible report summarising another report behind a

paywall in the FAZ, thus making the content of the FAZ work freely

accessible). This could be used for AI training under the research

exemption if access to the individual works was lawful in each

case, but even the Swiss research exemption does not allow for the

verbatim reproduction of a protected article; it only protects the

extraction of information for research purposes – which

includes the training of an AI model (see here). Incidentally, this is precisely the

distinction at issue in the New York Times dispute, i.e. the

reproduction of articles that were allegedly found on third-party

sites. Corresponding proceedings show that legal action can indeed

be taken against third parties who reproduce sources verbatim (see

here). However, what is often overlooked in

this debate on AI training is the fact that, even according to

statements from within their own ranks, the Swiss media seem to

have suffered insignificant harm from the mere training of AI

models with content that has long been published, at least if the

articles are not reproduced (which, technically, can only happen in

model training if an article is seen often enough during the

training process). It very rarely restricts traffic to their sites

and the gain in value for third parties is minimal to theoretical.

Of course, publishers would be happy to receive remuneration for

such uses but this would also be minimal to negligible for the same

reason. That is why the process of training large language models

does not really seem to be a problem. From an economic perspective,

the legal situation regarding traditional AI training seems largely

irrelevant to these rights holders. Furthermore, the law may not

provide the level of protection that makes it technically feasible

to reliably block data-hungry bots and prevent copies of articles

from appearing on other freely accessible websites. Practical

investments are also being made in this area – rather than in

legal battles directly against AI providers, at least in

Switzerland.

- Problem No. 2: What affects the Swiss media much more is a phenomenon known in the industry as "Google Zero". It describes a nightmare scenario in which all user traffic generated by Internet search engines such as Google on their online offerings shrinks to zero because users are already satisfied with the summaries provided by AI from articles and other content on their online offerings. Reference is made here to an already massive reduction in Internet traffic. Google's "AI Overviews" are said to have already reduced this web traffic by 34% (see here, here and here). Other examples include chatbots such as ChatGPT and Perplexity, which in turn compete with classic search engines such as Google by offering to search the internet for users. So, the tech companies are also undermining each other. These losses for content providers at the end of the chain are apparently not offset in any way by recommendations from AI services (where users can click on the sources of the summaries if they are actually interested, which should make these clicks much more valuable in themselves). The reasons is that this business is about mass, not a few genuinely interested readers. Less user traffic means less advertising revenue for certain media offerings. This – and not the training of AI models – is the real threat from the perspective of the Swiss media. Legally, as mentioned above, they have little recourse against such activities in Switzerland unless content behind an (effective) paywall is accessed directly or, of course, if the output contains more than summaries, quotations or short excerpts (see above). However, under current Swiss law, an opt-out signal on the website, even if machine-readable, is generally not sufficient to legally block bots from accessing otherwise public content. In practice, it often doesn't work anyway: a well-known Swiss newspaper publisher recently said it counted several thousand hits per week from bots on its newspaper website, with 98% of the hits ignoring the machine-readable opt-out,. That said, a distinction needs to be made here: firstly, there are many different types of bots, and only some of them have anything to do with AI training. Secondly, in some cases, media companies want and are economically dependent on their content being scanned by bots – in some circumstances even behind a paywall – so that it appears in internet search engines, for example, and can be found, clicked on and hopefully purchased. Bots are therefore not just a problem, and excluding them altogether with the "robots.txt" file is not a satisfactory solution. Indeed, there is no contradiction in allowing access to traditional search engines that generate traffic while denying it to AI applications that substitute content. However, as search engines increasingly become AI services, a dilemma arises because, on the one hand, the search habits of the public are changing, and certain tech providers do not allow differentiation for technical or contractual reasons, or media companies do not have sufficient bargaining power to enforce such selective consent. Here, too, differentiation is necessary: Media representatives admit that the industry leader Google is meanwhile an exception, as it provides website operators with technical tools that allow them to determine whether their content is used for AI training or internet searches by AI models (known as grounding) without affecting the findability of this content in normal searches (see here and here). However, these techniques must be used by website operators. Media industry representatives emphasise that they are not seeking to ban AI offerings, but rather to receive fair compensation for their content. Therefore, this is not a matter of theft or "misuse" of intellectual property, probably except for the verbatim reproduction of content aggregated on third-party sites. Instead, the goal is to create bargaining power, similar to that granted by EU copyright law with its opt-out provisions, which is currently lacking in Switzerland. The Swiss and other media outlets currently see themselves at a disadvantage in this regard – they have so far secured very few deals with AI providers, or at least not at the prices they would like; in the past, it was mainly large international publishers that were able to conclude contracts. However, deals for regulated access to high-quality content will be a matter of time. The main bone of contention will be the amount of the remuneration; opinions on this will vary widely. This is not just about AI, but also, for example, the price that providers such as Google have to pay in the EU for media snippets. However, this is a separate issue that is also being discussed in Switzerland under the heading of "ancillary copyright for press publishers" or "press publisher's right" and will not be addressed here (see here). The ongoing revision of the law could at least form the basis for an adjustment of the rules on AI, but more on that later.

Of course, there are other creative professionals besides those in the Swiss media who feel threatened by AI – and various other professional groups as well. They often take a back seat due to the focus on the media. They argue that AI has the knowledge it has today from their content and is now using this knowledge in its own work because it can produce content that is good enough for many people much more cheaply and quickly than creative professionals. We will leave aside the question of the extent to which displacement is actually taking place; this is certainly an important issue for the economic and social policy debate that should be conducted here (more on this in a moment). It should be noted, however, that – unlike the examples from the Swiss media – this is also a matter of (free) competition: Market participants have always been inspired by their competitors to do things better, cheaper, or faster, which has often improved the range of products and services on offer. Unless content protected by intellectual property rights is reproduced or a marketable work product is adopted and exploited without reasonable effort on the part of the original creator, this behaviour is not only permitted under Swiss law, but even legislatively desired.

Is this really a case of abuse?

But is it really that simple – or even an outdated view? First of all, we should be aware that the debate on copyright in the use of AI in Switzerland is currently still predominantly emotional and generalised, at least outside expert circles. For example, the use of media content by AI providers is regularly referred to as "misuse". In connection with AI, there is also repeated talk of "theft" of intellectual property, even in cases where this legally has no merit. Even scientific articles on the subject attract hateful comments, for example, when they question whether and to what extent machine learning differs from human learning from a copyright perspective, particularly when both result in the creation of new content inspired by the one seen during training. Such questions strike a nerve and must therefore be discussed without blinders. Much like it must also be discussed whether inventions made by AI can be protected by patent law and by whom (see here, for Switzerland, where a court ruled that AI cannot be an inventor within the meaning of the law).

On the subject of "misuse" or "abuse", it should also be remembered that misuse is a violation of recognised rules, norms or laws, and whether this is actually the case here in Switzerland is open to debate. But which rules for AI in the field of copyright law are recognised and, secondly, violated in the cases at hand?

The standard that is somewhat established is the Robots Exclusion Standard with which the operator of a website can use the "robots.txt" file on their server to determine which parts of their website may be searched by a robot and which may not (see here). If this is not observed, it can at first sight certainly be considered misuse. But it is not necessarily that simple. Counterarguments are that compliance is voluntary, it does not allow for differentiation based on the purpose of use, i.e. it is always all or nothing (although specific bots can be addressed), and it does not refer to rights holders, but to website operators (which, of course, may be irrelevant for publishers). It also doesn't regulate what may happen with the content found, but only whether it may be scanned or indexed. That, however, is not the real problem. A standard suitable for today's needs is still being worked on. But above all, we should ask: Does and should such a standard also apply to cases like problem no. 2, where a single user instructs a computer to perform a web search for them and summarize the result? Or is the tool used by the user simply none of the website operator's business? These cases were not the focus of its development (originally in 1994) because they did not exist at the time. Is this therefore really a case of misuse?

The real problem seems to be that society is confronted with a new phenomenon for which the applicable rules are not yet clear. It is therefore necessary to first define what constitutes misuse and to question whether existing regulatory concepts – in copyright law or elsewhere – are still fair. This question is much more complex than the respective camps portray. To take the present constellation: Although in many cases there is no direct copy of a work, the central concern of many rights holders is the so-called substitution effect: the danger that AI-generated content will replace the original works on the market and undermine their value. This issue is the subject of intense international debate, particularly in US law under the heading of "market dilution". There, courts are dealing with the question of whether the use of copyright-protected works to train an AI model can be considered "fair use" (and thus permitted) if this model subsequently generates a potentially infinite number of competing works and could thus significantly damage the market for the originals. US judges have at times stated that a technology that is both highly transformative (i.e. does not merely create copies and therefore does not infringe copyright in the US) but also has the potential to massively dilute the market for the underlying works represents a new challenge for copyright law. This is not abuse, but rather a challenge that requires political decisions on possible system changes – and a corresponding data basis. This is because it is controversial how high the substitution effects actually are, i.e. whether – to stay with the example of media – today's media audience is really switching to services such as ChatGPT or Perplexity instead of continuing to consume media directly. Conversely, it is obvious that users are looking for ways to manage the ever-increasing flood of information – and AI offers a ready solution. And not only there: AI providers are setting out to replace the "eyeballs" of human users in general. OpenAI and other companies have already launched services that allow virtual "agents" to be commissioned to perform tasks independently on the internet, such as finding the best deal for a product – unaffected by any psychological tricks employed by online shop operators. The latter must therefore also prepare for a new reality, as must many other industries.

This debate raises a fundamental question that is also relevant for Switzerland: Should copyright law be further developed in light of technological developments in order to protect not only the concrete form of a work, but also against such substitution effects, insofar as they occur and must be considered market-distorting? Or is this primarily a question of competition law? And what constitutes market distortion as opposed to the desired course of competition and innovation? The fact that the substitution effect is being discussed as a key criterion for possible copyright regulation can be seen as an indication that the understanding of copyright law is currently undergoing change. It is no longer just a matter of protecting against piracy, but increasingly of ensuring fair market conditions in an information economy shaped by AI. The US Copyright Office, for example, has already clarified that commercial AI applications that use large amounts of protected works to generate content that competes with them in existing markets could exceed the limits of "fair use" (see here and an analysis here), for example.

The supposed solution: an adaptation of copyright law

Unfortunately, this discussion is only just beginning in Switzerland, and yet, a different path is currently being taken here. A supposed solution to the problems mentioned has been on the table since last year in the form of a so-called motion (a legislative proposal) against the "misuse of AI". It was drafted by Petra Gössi, a member of the Swiss Council of States and liberal party FDP, who is also a lawyer. The exact circumstances surrounding the motion's origins are not publicly known. However, experts suspect that the Swiss Media Association (VSM) may have played a key role in initiating it, as the motion places particular emphasis on journalistic content. In any case, the VSM supports the motion. Either way, the aim is clearly to address the two problems mentioned above in the Swiss media, but as experts are observing with concern this seems to be being done with a sledgehammer.

The Federal Council is being asked to amend copyright law as follows (see here):

- The consent of the copyright holder is required if journalistic content and other original creative works are selected, processed and reoffered in any way for generative AI services – as rights of use under Art. 10 para. 2 URG or the general clause in para. 1.

- The provisions on exemptions (in Art. 19 para. 3, if applicable Art. 24a, 24d and 28 URG) must clarify that such public services and offerings cannot invoke exemptions or limitations to copyright.

- Swiss law is applicable and the courts in Switzerland have jurisdiction if content is offered in this way in Switzerland.

The motion is unusually specific in its wording. Its demands should be understood to mean that journalistic content and other works and services covered by copyright should receive "comprehensive protection" when used by AI providers. If it is accepted, the Federal Council must propose an amendment to the Swiss Copyright Act in line with these requirements. It is therefore worth analysing the three paragraphs in more detail.

Step 1: GenAI offerings require the proactive consent of all rights holders, even if their works are not reproduced

Any use of copyright-protected content already requires the rights holder's consent, provided the content's individual character remains recognisable. For instance, if an AI chatbot reads a newspaper article and reproduces substantial parts of it, this constitutes a copyright-relevant act under current law. Such an act is only permissible with the rights holder's consent, unless an exemption applies (see clause 2). Since this principle is already established, and it does not solve the Swiss media's problem any better than the current law, clause 1 must be interpreted more broadly. The wording "in any way" further supports this broader interpretation. This wording indicates that the intention is not to create a regulation that is as narrow and specific as possible, but rather that it should be interpreted as broadly as possible. The motion's introductory sentence also calls for "comprehensive protection". This implies that the rights holder's consent is necessary even when an AI service processes a protected work to the point where it is no longer recognisable. Therefore, consent is required if an AI service uses protected content but alters it so extensively that the original work's individual character is lost and then offers the altered content. This contradicts the concept of copyright, which protects only a specific expression—in the case of text, the specific wording—but not the underlying information. The motion goes further, proposing that if an AI extracts information from a copyrighted text, the knowledge contained therein should belong to the work's copyright holder, at least at the expense of the AI provider. This would be a departure from the established copyright principle that ideas and information as such are not protectable, only their concrete form of expression.

A counterargument is that focusing on the output ignores upstream acts of use. This criticism, however, overlooks that these upstream acts must also comply with copyright law and are assessed separately. The actual problem is that for the large, foreign AI providers relevant here, Swiss law possibly does not apply to these upstream uses when the AI is trained abroad, for example, in the United States.

The regulation applies not only to information in journalistic works but also to any other content considered an "original creative achievement". While this term is new to copyright law, it presumably covers all copyright-protected content. This under Swiss law includes images lacking individual character, as they still result from a human creative act. It will be up to the courts to clarify whether this constitutes a "creative achievement". The motion's introductory sentence also clarifies that it aims to cover all works and services protected by copyright.

The restriction should only cover cases where a genAI service "reads, processes, and reoffers" a work. The term "reoffers" implies providing a work that the user does not yet possess. Consequently, a genAI service that only processes content previously supplied by the user, such as in the context of a translation tool, would not fall under this restriction. This approach would be sufficient for Swiss media outlets, as their primary concern is the initial distribution of their content to the public. Whether a user employs AI to translate an article they already have is irrelevant to this concern.

However, clause 1 likely applies if the user permits a genAI service to search the internet for content to answer a question, which the service then provides to the user. It is irrelevant whether the service offers a link or a summary, as in both cases, the genAI service reads and processes the original work on its servers to determine if the content matches the user's query. The fact that the service provides only a link or a summary, rather than the work itself, must be irrelevant because otherwise clause 1 would not be required as a provision in the first place. The mere transfer of information, even without reproducing the work, thus seems sufficient to trigger the provision, and it is intended to make such acts subject to the rights holder's consent. At first glance, this would solve half of the Swiss media's problem (the other half requires section 2, see below). A separate question is how to prove that a genAI provider based its output on specific works if the text does not cite them. However, there are signs of increased transparency, even among major providers, partly because the EU AI Act requires it. Most major AI developers have also signed the EU's recently published "General Purpose AI Code of Practice," which also contains transparency regulations (see here).

Can an AI model still answer questions about the deselection of Christoph Blocher?

Problem no. 1 – the training of a language model – is also covered by the proposed regulation. A model does not store the content it reads during training. Instead, it uses this content to develop higher-level language skills and general knowledge. A model only memorises text that appears frequently in the training data. In such cases, the model might reproduce the text in its output, particularly with a specific prompt. However, existing law already addresses this as an infringement of the rights holder's exclusive rights, making new regulation unnecessary.

The Gössi motion, however, goes much further. Clause 1, broadly interpreted, covers any offering of large language models. As training an LLM requires vast amounts of data, it is unlikely that any have been trained exclusively on proprietary content or with the proactive, prior consent of all rights holders. This raises the question of whether operating an LLM, for instance through a service like ChatGPT, constitutes a "reoffering" of the original training works. A narrow interpretation would require the works to appear as such in the output. However, this would render clause 1 redundant, as current law already covers such cases. Therefore, a broader interpretation is likely intended, where an offering is covered even if the output contains no individually characteristic parts of the original works and the developers did not obtain prior consent from the rights holders.

For example, if a language model is asked, "How was Christoph Blocher [a well known Swiss politician] voted out of office?", it will likely provide an answer based on Swiss media reports used in its training. Does offering such a language model—whether as a chatbot or an API for other AI applications—constitute "reoffering" this media content? The answer is likely yes, as the service consists of the generated output. In this case, the output includes information the model "learned" from nn newspaper reports about Christoph Blocher's deselection. It is irrelevant whether nn is 1, 10, or 100. AI services are designed to evaluate vast numbers of sources and synthesize them into a result. This process typically means that the individual character of a specific journalistic text is no longer recognisable in the output, and copyright therefore does not apply. Furthermore, a model does not memorize knowledge from a single text after seeing it once; the text must be seen multiple times, or the information must appear in many texts, to be incorporated and reproduced. This contrasts with problem no. 2, where a single text might suffice. There is no indication that such cases should be exempt from clause 1, or that clause 1 only protects "exclusive knowledge" from a single source. According to the Gössi motion, it is also irrelevant that the information about Christoph Blocher's deselection is factual and thus not protected by copyright. Moreover, in our example, the rule in clause 1 is triggered not only by journalistic content but by any copyright-protected content.

Clause 1 raises the question of whether it imposes further restrictions. One interpretation is that a relevant act requires a genAI provider to read, process, and reoffer content cumulatively. This would allow circumvention by splitting these tasks between different companies: one could read and process the content, while another offers it. This interpretation seems unlikely, as it would create an easily exploitable loophole. Anyone who trains a large language model necessarily processes content and typically becomes the provider of that model, unless it is used exclusively for internal purposes. While one might argue they only offer the model and not its output, this is often not the case in practice. For instance, companies like OpenAI and Google train the language models they offer. In contrast, Microsoft currently offers primarily third-party models, such as those from OpenAI.

Only (but at least) the offering must take place in Switzerland

A narrow interpretation might require all partial acts—reading, processing, and reoffering—to occur in Switzerland for Swiss copyright law to apply. However, clause 3 suggests that Swiss law applies even if only the offering takes place in Switzerland and even if the provision lacks complete clarity. Currently, Swiss copyright law generally does not apply when the training occurs abroad, even if it involves crawling Swiss content from outside Switzerland (no reproduction takes place in Switzerland, as the web server sends the content abroad itself). The training of a model and its offering are distinct acts requiring separate legal assessment. Consequently, a Swiss court is unlikely to apply Swiss law to the crawling of public content in Switzerland for training conducted abroad. To strengthen the protection of Swiss content used abroad, the motion would need different wording. As drafted, it only covers the offering of AI products in Switzerland (regardless of where they were created), but not the offering abroad. This creates a loophole: A provider relying on Swiss content could circumvent the regulation by ceasing to offer its services in Switzerland while continuing to serve the rest of the world.

In summary, if this motion is implemented, offering large language models in Switzerland would require proactively obtaining consent from the rights holders of all copyright-protected sources. This would apply even if the output does not reproduce these sources in whole or in part, but only contains general knowledge derived from them – for example, the fact that Christoph Blocher was voted out of office. This latter requirement is particularly noteworthy as it would upend a core concept of copyright law. Of course, legislative countermeasures, such as a collective licence (discussed below), could neutralise this effect.

Step 2: Traditional copyright restrictions such as the right to quote or personal use are abolished for GenAI providers

he rights holder's exploitation interests and those of individual users and society. Copyright law provides for so-called "exemptions", i.e., limitations to the right owner's rights, for this purpose. This balance is reflected in statutory exemptions such as the right to quote and provisions for personal use. For example, individuals may print a copyrighted artwork for their private home, and companies can make internal copies of protected works, such as printing a webpage for their files. In return, collecting societies handle collective compensation for such uses, a system that functions effectively.

The motion also seeks to abolish this cornerstone of copyright law for cases under clause 1. This is presumably to prevent providers responsible for problems no. 1 and no. 2 from invoking it to circumvent the extended consent requirement.

The extent of the abolition of current exemptions for AI providers is not immediately clear. While the first part of the sentence refers only to specific exemptions, the second part of clause 2 is formulated in absolute terms. This could mean, for example, that rights such as quotation, parody, or personal use would also be abolished for genAI providers.

The first sentence refers only to specific limitations: training language models for scientific purposes (Art. 24d), internet caching (Art. 24a), media reporting (Art. 28), and personal use outside the private sphere (Art. 19(3)). Notably, Art. 19(3) is not a exemption but an exception to the exemption. This detail, along with the phrasing "where applicable" and "not to exemptions or limitations" (instead of "not to these exemptions or limitations"), suggests the motion aims to remove all exemptions AI services could rely on. The explanatory notes clarify this, citing personal use, the research exemption, and the exception for transient or incidental reproductions merely as examples ("in particular"). Even if the motion were limited to just these three examples, clause 2 would still be very far-reaching.

It is also unclear whether the removal of restrictions applies only to providers of generative AI who process copyrighted works under clause 1, or to all AI providers. The wording of clause 2 is indistinct and its reference is ambiguous. Conceptually, however, the provision clearly targets generative AI, as the service it provides must also be content. For instance, if an AI model is trained with copyright-protected images to recognise objects or moods, it does not offer these images as content, not even indirectly. This distinction is relevant because other AI applications may also be trained with copyright-protected material.

The consequence: some AI offerings in Switzerland would effectively be banned

The proposed combination of clauses 1, 2, and 3 would, if implemented into Swiss copyright law as described above, significantly impact the provision of generative and other AI services in Switzerland. One representative of the tech industry even spoke of the world's strictest copyright regulation in connection with generative AI. Without countermeasures to neutralise its effect, it has to be expected that many currently available services could no longer be offered in a legally compliant manner, effectively banning them in the end. Yet, it is necessary to distinguish what the motion's implementation would mean without such countermeasures:

- Language models: Providers of large language models (LLMs) and other AI models trained on copyrighted content might withdraw their services from Switzerland. Under the proposed clause, it would be sufficient for a model to have been trained on such content for copyright infringement to occur. It would no longer matter whether the model's output recognisably reproduces copyrighted works. Since proactively obtaining consent from all rights holders is impractical, and existing copyright exceptions would no longer apply, these AI offerings would become non-compliant. The legislator created these exemptions, often involving collective management fees, precisely because obtaining individual consent is frequently impossible. Abolishing the private use exemption would also eliminate the compensatory levy under Art. 20 of the Copyright Act. Alternative mechanisms like extended collective licensing present their own challenges (see below). Consequently, an AI provider would face legal and potentially criminal risks by operating in Switzerland. While a provider could contractually shift the responsibility for securing rights to its users and seek indemnification, this approach is questionable, particularly as it may not be effective against criminal liability and the core issue arises during the model's training phase. Requiring users to promise not to generate new content would render the models useless for most applications, including the numerous chatbots and custom solutions companies have already developed using LLMs.

- AI services that convey third-party content: The provision of chat services such as ChatGPT or Copilot for Switzerland would be restricted. This is due to the output the language models generate from their own "knowledge" and because of additional functions that enable internet searches. Some services, like Perplexity, even specialise in this, but ChatGPT, Google Gemini, and Microsoft Copilot also offer such features. These AI services, with or without internet search, are used intensively for private and business purposes. When accessing the internet, they invariably use copyright-protected content, and it can never be guaranteed that the rights holder has consented. Although "opt-out" signals allow website programmers to instruct bots from search engine and AI companies to refrain from indexing content, this mechanism is not universally applied and does not solve the underlying issue (as discussed below). Clause 1 requires the rights holder's consent, not merely the absence of an opt-out, which differs from approaches in other countries. This consent must come from the rights holder, not the website operator.

- AI services that do not transmit third-party content: The situation is less clear for AI tools that "only" process user content, such as translation services like DeepL. Although these services read, process, and return copyright-protected content, the user provides and controls it. In a 2014 ruling concerning a document delivery service (DFC 140 III 616), the Federal Supreme Court attributed the service's actions—copying scientific journals on request—to the client (Consideration 3.4.3). Consequently, sending the copy to the client was not an independent copyright infringement; instead, the key question was whether the client held the necessary rights or could rely on exemptions. In the same ruling, however, the court clarified that stricter rules apply when users engage third parties for reproduction compared to making copies for purely private use (Consideration 3.5.2). It is therefore uncertain whether clause 1 applies to genAI services where the user provides all content for transformation, such as in translations or text corrections. We currently believe clause 1 and 2 do not apply in these cases, as it is intended to cover only actions attributable to the provider. Conversely, as stated above clause 1 and 2 likely apply where an AI service independently searches the internet on behalf of a user (e.g., "Create a summary of Swiss reactions to Donald Trump's tariffs"). One could argue that this action should also be attributed to the user, treating the AI as the user's extended arm. Under this view, copyright provisions addressed to the user would not apply to the service, and such offerings would remain permissible without the rights holders' consent. However, such an interpretation would undermine the core concern of the motion ("comprehensive protection") and would therefore likely not prevail. Another argument against this is that in these cases, it is not the user but the AI that determines which sources are used for such a search.

- Search services: Internet search services, such as Google, now rely heavily on AI, which has evaluated search queries for years. While this practice is unlikely to fall under clause 1, the regulation would cover AI-generated short summaries or snippets of websites. For the reasons mentioned for AI services, these would effectively no longer be permitted in Switzerland.

- Research: Swiss AI research would also be affected. ETH Zurich and EPFL Lausanne recently announced the first major Swiss language model (see here), earning worldwide acclaim. Commentators see this as an important step in the area of digital sovereignty for Switzerland. According to reports, only content from websites that had not prohibited this by means of a machine-readable opt-out was used for training purposes. Implementing the motion as required by clauses 1-3 could make such initiatives impossible; one could argue, though, that the motion's reference to "commercial" providers exempts institutions like ETH and EPFL. Yet, the negative impact on Switzerland as an AI research hub would still be considerable. Research also depends on services from commercial AI providers. It comes as no surprise that Swiss AI researchers consider the motion dangerous and do not support it.

Will Switzerland – and its media – score an own goal?

Critics fear the proposed regulation will significantly restrict Switzerland's access to GenAI services, ultimately harming the country itself. They argue that Swiss media companies could be more severely affected than the AI providers the regulation targets. Several examples illustrate this concern: Journalists using AI-supported tools for research might lose access or face limitations, increasing their workload and reducing their competitiveness, especially when it comes to foreign publishers. Publishers risk losing access to essential language models for their own AI applications, as providers may be unable to meet the stringent requirements of clause 1. Even when using their own models on their own content, publishers would face legal uncertainty. Media contributions often include third-party material, such as quotations, which are permissible under current copyright exceptions. If the motion is implemented as demanded, publishers, as providers of services with GenAI components, could themselves no longer rely on these crucial exemptions.

Representatives of the Swiss media do not see any such consequences. They emphasise that they are only concerned with fair remuneration. This can be achieved through licences. In their view, the legal regulation demanded is much less strict than the wording of the motion suggests. The possibility to rely on copyright exemptions, as today, would be only partly limited. And according to clause 1, "consent" effectively means only a right of objection. However, this does not seem particularly convincing. To permit someone to say "Do not do this" is not the same as requiring it to say "Yes, you may." Although there is the concept of implied consent when content is posted on the internet with the knowledge of AI bots, it has considerable pitfalls and, as shown above, is not considered a reliable basis. The media houses apparently rely on the motion not being implemented as absolutely as it is presented.

The motion itself is very clear, though: it is about finding a consistent and effective solution to the problems mentioned in the Swiss media, and it certainly does that. The catch is that it accepts enormous collateral damage, which cannot be prevented even with concepts such as implied consent or individual licence deals with media outlets. Legally, it is irrelevant how the motion's author would like her motion to be understood today in light of the emerging criticism. She can no longer withdraw it. Of course, the Federal Council could simply decide not to follow the Gössi; parliament would have to oppose an implementation that was too lenient. Also, the Gössi motion could be "neutralised" with a new form of extended collective licence (see below). However, it is questionable whether it really makes sense to supplement copyright law with mutually contradictory provisions instead of directly creating a clear legal basis for AI use with the necessary opt-out, thereby meeting all requirements – legal certainty and protection.

Another unaddressed problem arises: if the primary concern is AI companies ignoring paywalls and the issue is not a lack of legal recourse but its enforceability, it is questionable what new legislation would achieve. Are the hurdles for rights holders to take legal action regularly too high? An amended copyright law would likely not change this.

Furthermore, this is a matter of competition within the framework of applicable law. There are no loopholes or gaps in the law, only changed economic realities. Of course, legislators may consider protecting certain industries from such changes through regulatory intervention and using competition policy laws. However, this should be stated honestly.

It should also be borne in mind that experience shows that technological change cannot be halted by regulation (see for example the explanatory report on the consultation in the area of ancillary copyright law, here). However, the impression is that this is precisely what is at stake here. Finally, it should be noted that, according to the Swiss Federal Constitution, the legislature is not entirely free to intervene in competition, i.e. to protect certain market participants from others. According to Article 96(4) of the Federal Constitution, deviations from the principle of economic freedom, in particular measures directed against competition, are only permissible if they are provided for in the Federal Constitution.

It should be noted in passing that the motion only restricts AI providers when offering their services in Switzerland, not when using Swiss content in general. The motion does not prohibit developers from accessing content from Switzerland and using it to train their models or for the content of their AI services – as long as they do not offer these in Switzerland. A thoughtless legislative amendment would therefore primarily harm Switzerland itself.

An example of ill-conceived regulation of new technologies

In light of the above, the Gössi motion appears to be an example of how ill-conceived regulation of new technological developments despite the legitimate concern could backfire, or at least generate unnecessary uncertainty and effort. This is especially true when action is taken without in-depth knowledge of the legal, technical and other contexts, as is unfortunately often the case in the field of AI. It is, of course, understandable and right that politicians are thinking particularly hard about regulating AI and asking themselves what needs to be done. This is all the more so given that the issue is of concern to many people – and that many professional groups feel threatened by AI. However, it is not ideal if many people are simultaneously sawing off the branch they are sitting on. The use of AI, for example, has become indispensable in the media and creative industries – despite its negative aspects. Experience shows that the rollercoaster of emotions that always accompanies disruptive new technologies in the early years of awareness gives way to a certain degree of familiarity or disillusionment over time. The dust settles and we view both the negative and positive aspects in a little more relaxed fashion. Legislators should bear this in mind when regulating, and we have had good experience with this approach in Switzerland in particular.

What is somewhat surprising in the present case is the fact that the Federal Council recommended the adoption of the motion without comment. Perhaps the number of rejected motions got out of hand, and so it felt compelled to consent to a motion for once in order not to appear obstructive. Perhaps it assumed, based on the reasoning, that it would strengthen Switzerland's innovative strength without questioning what the regulation actually does. Whatever the background, it seems clear that the Federal Council's position is hardly compatible with the outcome of its AI regulation review, in which it outlined a legal framework that aims primarily to strengthen Switzerland's innovative strength. In the spring, the Federal Council gave the impression that it did not really see any need for change in this area (see here) and that it generally wanted to take its time with regulatory proposals until the end of 2026. Now, certain circles fear that if the motion is accepted, it could be implemented on a fast track as part of an already planned revision of copyright law. As is well known, the issue of ancillary copyright is already being discussed, which is moving in the same direction. The risk of such a "fast track" is that there will not be enough time to understand and discuss the issue and its solution, and to harmonise it with EU law, as is customary in Switzerland.

Resistance is growing – the political process

The Council of States has already approved the Gössi motion largely unnoticed by the public and experts and without much discussion. It is to be dealt with by the preliminary consultation committee of the National Council on 14 and 15 August 2025. The vote in plenary will follow at the beginning of September 2025.

If a motion containing specific legislative provisions is adopted by both chambers of the Swiss Parliament, the Federal Council is in principle bound by the mandate contained therein. This mandate obliges the government, under Article 120(1) of the Parliament Act, to draft a bill that meets the requirements of the motion. This process usually involves the federal administration drafting a preliminary bill, a consultation procedure in which cantons, parties and associations can comment, and finally deliberation and decision-making in Parliament. In practice, the Federal Council has some leeway in implementing such a motion, but this is limited by the detailed text of the motion. The Federal Council may not undermine the core content of the motion. It may not simply omit essential elements of the motion or violate its main purpose.

Even if the motion is accepted and referred to the Federal Council, nothing has been finally decided. Heated discussions are to be expected in the run-up to this. In the meantime, various stakeholders have realised how explosive the motion is for them and have begun fighting it. The divisions are deep and run right through the Swiss economy: large sections do not want any restrictions because they see them as a threat to Switzerland as a business location and to homegrown innovation, while others see their business fundamentally at risk in the absence of compensation provided for by law.

Incidentally, the motion would not be necessary. As mentioned above, the Federal Council is currently working on an amendment to copyright law in connection with ancillary copyright (see here) and could easily submit proposals to Parliament on its own initiative to address the issue temporarily in order to ease the pressure and facilitate discussion – which, according to well-informed sources, it probably intends to do. The regulations called for in the motion are reportedly not in line with this. Experts are also leaning in a different direction (see below).

Consideration should also be given to the signal that Switzerland would send out internationally if its parliament were to pass the motion anyway. Critics fear that Switzerland would disqualify itself as a centre of research and business if it were to signal to the world that it intends to impose massive legal restrictions on the use of AI in this country.

It will therefore be interesting to see whether the National Council will deal with the dossier with greater understanding of the issue and more foresight.

How things could be better – suggestions from experts

Even if the motion does not pass the National Council, the question remains as to how problem no. 1 and no. 2 outlined above can be solved. The initial acceptance of the Gössi motion clearly indicates that there is economic policy will to make changes in the law, and this seems reasonable. It is not entirely clear how far sympathy for rights holders will extend when the consequences for users and consumers of AI are discussed. While restrictions are to be lifted in the United States (according to the Trump administration, protected content should be available free of charge for AI training, see here), for example, the situation in Europe is not as one-dimensional. Traditionally, rights holders in Europe are well supported. However, the argument that Switzerland should be protected and strengthened as a location for AI innovation also resonates – in this regard, the Gössi motion is seen as clearly harmful by those who are actually involved in innovation.

In any case, the regulatory approaches of experts here are moving in a different direction in terms of how to better protect rights holders. For example, a recent study commissioned by the European Parliament proposed specific regulations in EU law to better protect rights holders when their content is used for generative AI and model training, and in particular to ensure that they are remunerated (see here). It emphasises the need for clear distinctions between input and output, harmonised opt-out mechanisms, transparency obligations and fair licensing models. A key proposal is the introduction of a remuneration system for authors whose works are used for AI training. In Switzerland this could take the form of collective licensing or a levy on AI-generated content administered by collecting societies. In addition, transparency obligations are called for to ensure AI developers disclose the use of copyright-protected content. The study recommends that the European Parliament lead reforms that take into account the changing realities of creative work, artistic creation, authorship and machine-generated content and strike a balance between innovation and copyright.

In Switzerland, Zurich professor Florent Thouvenin recently published a white paper proposing the introduction of a new exemption in copyright law to better compensate and protect rights holders whose works are used for training generative AI (see here). This restriction would allow the use of copyright-protected works for AI training in principle but would provide a right of opt-out for rights holders. This opt-out should be machine-readable to ensure efficient implementation. In addition, the combination of this restriction with a statutory licence providing for remuneration for the use of the works is being discussed, whereby rights holders could generally prohibit the use of their works by opting out and then grant licences to individual AI providers.

Should Switzerland align itself with the EU – at least as a first step?

The proposal for an exemption with an opt-out is largely in line with what already applies in the European Union in terms of copyright law: the regulation there is similar to the Swiss research exception (in the EU, this is referred to as the text and data mining exemption, or TDM for short). However, it provides for an opt-out in the commercial sector, which its Swiss counterpart does not. The TDM exemption is often cited as the legal basis for training AI models. The EU AI Act also takes up this provision and requires AI providers to show how they comply with it. Extending the Swiss research exemption to include such an opt-out could therefore be a temporary solution that would give time for discussion on an appropriate solution. However, Switzerland would lose some of its attractiveness as a location for companies that want to train models themselves.

However, this provision only solves problem no. 1, not the more serious problem no. 2. Solving this second problem by interfering with copyright law is much more delicate, as it ultimately involves the monopolisation of information, not of a specific work, since the latter is already protected under current law. Current legal and ethical principles suggest that knowledge from lawfully accessed works, such as published articles, should be freely obtained and shared. In essence, anyone should be able to relay information they have read. Using a reading aid, even one powered by AI, does not alter this principle. For instance, no one would prohibit a visually impaired person from using technology to search, summarise, and read aloud online content. This concept is supported by legal provisions like the exemption in Section 24c of the Copyright Act.

Problem No. 2 is therefore not based on principle, but on volume. It is unclear whether the fact that it is only a few companies that are skimming off users' "attention" is also part of the problem. If all users took out their own subscription to their favourite media outlet but instead had an AI agent read the online newspaper, the problem would not disappear entirely (the advertising in the newspaper would be in vain), but the subscription fees would still be there. However, it is argued that it is not the paid services that suffer here, but the content behind the paywall, which is mostly financed by advertising. This would be just as affected by personal AI agents, because the impact of advertising and thus an important source of income would also be lost.

Compensation through collective management as a compromise?

One possible approach could be to expand an existing model in the area of collective management, which provides for compensation for digital copies made by AI agents. In the current world, there is the "Kopierrappen" (copy penny), a compensation paid for each internal copy of a work, which compensates rights holders, as mentioned above, for the economic use of their works within the scope of the limitations (i.e. internal use). It is calculated purely statistically and only applies above a de minimis threshold and in the commercial sector.

The decisive factors would be the structure of the tariff, which could be graded according to economic yield, and the distribution of revenues. The appeal of such a solution would be that it would not require any manipulation of the basic principles of copyright law – with the corresponding unintended consequences. Instead, a clever tariff structure could be used to allocate a fair share of the economic profits of AI service providers to rights holders. Various tariffs of this kind already exist, the system has been introduced and is basically working. It is not even clear whether a legal amendment would be necessary.

However, the solution has several drawbacks. One is that it only gives AI providers limited legal certainty; they would be likely to demand that it be made clear thatthey are allowed to use the content in question for their own purposes. Another drawback is that it would no longer be the rights holders who could negotiate their revenues on a case-by-case basis through licence agreements. Instead, the tariff would be set across the board, and this would likely result in minimal payments given the negligible contribution of individual pieces of content. In addition, it remains to be seen what the major providers will earn from generative AI; today, a lot is being invested, but much less is being earned. AI is relatively cheap today, which – as rights holders will say – is precisely one of the problems (it is therefore foreseeable that they will demand higher prices in order to be better compensated themselves). However, those who want to negotiate licence revenues themselves could simply (and effectively) put their content behind a paywall and regulate access by contract. This would also achieve their goal. In discussions with representatives of Swiss media companies, there are indications that collective management could be a viable option in their view. It remains to be seen how other circles feel about this – and whether Switzerland can and should go it alone in this area.

Extended collective licence – a solution that already exists?

Another solution being discussed among experts that builds upon the idea of collective management is the model of extended collective licences (ECL). This instrument, which already exists in Swiss copyright law (Art. 43a URG), could offer a pragmatic solution to the complex compensation issues in the AI age. An extended collective licence allows a collecting society (such as ProLitteris for texts and images) to grant licences for the use of a large number of works. What is special about this is that the licence covers not only the works of the society's members, but also those of non-members ("outsiders"). This can solve the problem that it is practically impossible for an AI provider to obtain consent from every single rights holder on the internet. However, rights holders who do not wish to participate in this system have the option of explicitly excluding their works from licensing by means of an "opt-out".

Representatives from the media industry seem to see this model as a viable way to ensure fair remuneration for the use of their content by AI services. This model could also create legal certainty and a single point of contact for AI providers. The concern expressed by critics that it is not practicable because the rights holders of content on the internet cannot be identified is correct in principle, but it describes precisely the problem that the extended collective licence was designed to solve. The collecting societies act as trustees in this case and also hold the revenues available for rights holders who are not represented.

Why collective management could also become a token exercise

However, a critical examination reveals further challenges: the sheer volume of content available online far exceeds the previous use cases for ECL and collective management. The bureaucratic effort involved in traditional management by collecting societies is already perceived as enormous by some, even though the repertoire of protected works in existing cases (e.g. music) is large but still limited and the stakeholders are known.

An extension to all copyrighted, public content on the internet, even if this were limited to the territory of Switzerland, raises questions not only of practicability but also of economic viability. Corresponding databases would have to be built, and, since it is not just about text and images, several collecting societies would be involved in parallel. In the event of claims, it would have to be checked in each case whether the work is actually protected. In addition, the scope of an ECL would have to be distinguished from other uses that have already been compensated for or from forms of use that are already permitted, as there is no room for an ECL in these cases. The costs for the maintenance of this administrative apparatus would be deducted from the revenue (the sometimes high administrative costs of collecting societies have already given rise to discussions in the past, even though the societies have been found to work efficiently).

Another hurdle is that, under current law, an ECL is granted to a licensee on a case-by-case basis. Every AI developer who wants one would therefore have to negotiate with ProLitteris, Suisa and all the other relevant collecting societies (if the same works affect several societies, they have to at least agree on a "Joint Tariff"); in any case, the ECL is not a general solution at present (examples see here).

Finally, determining an appropriate tariff is likely to be a tough nut to crack. How should it be calculated? A licensed use is legally out of the question for an ECL if it impairs the normal exploitation of protected works and services, which, however – where problem no. 2 is concerned – could be the case from the perspective of media houses; this is where the shoe pinches. Although they would probably be the first to declare an opt-out anyway, the rule also means that compensation based on the loss of revenue caused to the rights holder in any relevant amount due to the use of their works would be systematically excluded today. The contribution of individual content to the value creation of global AI models is, as shown, inherently minimal. However, if all content were licensed together, the calculation could look different again, but then the question arises of distributing micro-amounts to individual rights holders, who may never claim them due to lack of relevance or knowledge, and the trust-managed licence fees would continuously grow.

Some of these criticisms could, of course, be resolved by amending the law, for example in the form of an extended "general" collective licence as a standard solution for all content whose rights holders have not actively objected or with alternative uses of licence revenue not claimed within a deadline. This would have to be combined with a technically simple, machine-readable opt-out standard, which the ECL does not currently provide for; the opt-out must be declared differently there. However, rights holders who wish to negotiate individual and potentially more lucrative licence agreements could continue to do so by protecting their content behind effective paywalls and excluding it from the collective licence. For everyone else, such a system could, at first glance, indeed enable uncomplicated and legally secure use by AI services in return for a flat-rate remuneration.

Such a model would probably also be necessary if, in the worst case scenario, it were necessary to neutralise the side effects if the motion by Gössi was actually implemented: although the law would require the consent of all rights holders, such consent would be granted on a general basis by the collecting societies in return for remuneration for content without the option of opting out, by virtue of a new legal competence to be created. This would, of course, be somewhat contradictory to the motion, which aims to remove legal exemptions.

Given these challenges, the question naturally arises as to the efficiency and usefulness of such a system. The legislator could claim to have created an instrument for fair compensation – which would be formally correct. However, if a large proportion of content creators do not benefit from this, little will be gained; the major players among the rights holders will get their "deals" even without such a regulation. Ultimately, there is a risk that nothing will come of it except expenses. It remains to be seen which providers would participate in such a solution under these circumstances.

Incidentally, these problems and the approach to solving them are not entirely new: over 20 years ago, Google began scanning millions of books and making them available online. The company cooperated with some publishers but also digitised books from libraries without the consent of the rights holders. This led to various lawsuits. An interim settlement failed. Finally, in 2015, a court ruling classified Google's actions as "fair use" under US law. However, the original settlement agreement from 2008 had provided for compensation for books already scanned and an opt-out system, the implementation of which had also begun. Economically, the settlement would have brought little benefit to the individual rights holders, even if it had been upheld. Google ultimately prevailed.

There are, of course, other models that could be used to draw lessons from what has been said. One could be to oblige large AI providers to pay into a pot from which creative artists would receive targeted support. This could be an alternative for the current system of collective tariffs, which first calculates how much of the revenue is attributable to which website. AI providers could meanwhile be granted greater legal certainty for their training and use. However, it seems questionable whether such a redistribution model would really solve both the problems no. 1 and no. 2 facing the Swiss media. We would also have definitively left the area of copyright law and would be closer to something like a turnover-based film promotion obligation or tax, as now applies to streaming services in Switzerland (see here).

A complex issue – let's take the time to address it

The complexity of the issue highlights the risks that can be associated with rapidly advancing regulatory intervention in new technological developments, particularly with regard to unintended negative consequences. This case also shows why we should take more time not only to discuss possible regulatory concepts, but also to understand exactly what is happening and how everything is connected, so that we do not throw the baby out with the bathwater or create something that ultimately achieves nothing.

Switzerland has always fared well with a cautious approach to regulatory issues concerning new technologies and has thus been able to learn from the mistakes of others. This is another reason why the Gössi motion is problematic. It comes at the wrong time and with a solution that is too specific to be implemented given the current state of knowledge and discussion, even if the fundamental concern for better protection and balance in favour of rights holders is (rightfully) supported. Gentler approaches, such as the introduction of an opt-out right, seem to be capable of achieving consensus, at least as a first step and to bring Switzerland into line with the EU, and probably also the inclusion of some form of compensation obligation.

The question also arises as to how an industry should act, irrespective of legal protection or compensation. The Swiss economy would be well advised to proactively adapt its business models to AI to avoid depending on such measures. History shows that defensive strategies aimed at protecting existing privileges are rarely successful against technological progress in the long term. With this in mind, at least some Swiss media outlets have rightfully made the use of AI a high priority.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.