- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit, Technology and Law Firm industries

- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in United States

- with readers working within the Law Firm industries

- within Intellectual Property, Media, Telecoms, IT, Entertainment and International Law topic(s)

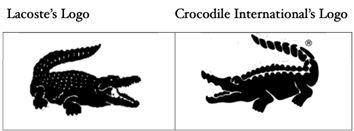

Illustrious tennis player René Lacoste was famously

regarded as 'Le Crocodile' – an association he

extended to his sportswear brand 'Chemise Lacoste'. Shirts

featuring an embroidered crocodile symbol were first introduced in

France in 1927 and marked the origin of clothing brand

Lacoste's popular logo  .

Registrations for the crocodile device and word mark LACOSTE were

subsequently sought in several jurisdictions. In India, Lacoste

obtained a registration for the crocodile device and logo mark

together (No. 400265) as well as the crocodile device by itself

(No. 400267) in 1983 in class 25. Use began a decade later in

October 1993. The crocodile device was also registered as an

artistic work under the Indian copyright statute (No.

62692/2002).

.

Registrations for the crocodile device and word mark LACOSTE were

subsequently sought in several jurisdictions. In India, Lacoste

obtained a registration for the crocodile device and logo mark

together (No. 400265) as well as the crocodile device by itself

(No. 400267) in 1983 in class 25. Use began a decade later in

October 1993. The crocodile device was also registered as an

artistic work under the Indian copyright statute (No.

62692/2002).

Meanwhile, Singapore based fashion brand - Crocodile

International – claims continuous use of the 'crocodile

family of marks' worldwide, including the composite logo  ,

since 1947 for clothing, sports equipment etc. It too holds

registrations in Class 25 in India, one, in fact, pre-dating

Lacoste, for marks entailing the word 'Crocodile' along

with a corresponding device (No. 154397 dated June 12, 1952 as well

as a later registration under No. 540315). It began using these

marks in India around 1997.

,

since 1947 for clothing, sports equipment etc. It too holds

registrations in Class 25 in India, one, in fact, pre-dating

Lacoste, for marks entailing the word 'Crocodile' along

with a corresponding device (No. 154397 dated June 12, 1952 as well

as a later registration under No. 540315). It began using these

marks in India around 1997.

Soon afterwards, Lacoste alleged that Crocodile International

had begun using a standalone version of its crocodile symbol  ('disputed logo') that closely resembled its own. Thus, it

filed the present suit (Lacoste & Anr. v. Crocodile

International Pte Ltd & Anr., CS(COMM) 1550/2016) for

copyright and trademark infringement as well as passing off before

the High Court of Delhi.

('disputed logo') that closely resembled its own. Thus, it

filed the present suit (Lacoste & Anr. v. Crocodile

International Pte Ltd & Anr., CS(COMM) 1550/2016) for

copyright and trademark infringement as well as passing off before

the High Court of Delhi.

Crocodile International's defence centred on a co-existence agreement dated June 17, 1983 wherein both parties had agreed to concurrent usage of certain trademarks (including the exact mark under dispute in the present case) in several territories (though not India). It further argued that through a Letter dated August 22, 1985, the parties' understanding was expanded to include Korea, India, Bangladesh and Pakistan.

Per Lacoste, the 1983 Agreement did not extend to India.

Prior Rights In India

According to the court, Crocodile International was the prior registrant and user of a 'composite crocodile device' in India, but this did not automatically confer rights over any and all variations of its composite crocodile trademark. Lacoste was able to prove proprietary rights over its standalone crocodile device through its 1983 Indian registration (No. 400267) as well as documentary evidence supporting use since 1993. This timeline predated Crocodile International's claimed use (since 1997) of its standalone crocodile device. Thus, when it came to a trademark comprising a logo of a crocodile unaccompanied by a word element, Lacoste had prior rights in India.

Deceptive Similarity

Further, since both trademarks feature a crocodile for garments, the court concluded they were conceptually identical. The overall silhouette of both crocodiles, including the head shape, arrangement and pattern of scales on the back, body curvature, and tail positioning, was found to be almost indistinguishable. Both designs conveyed a similar aggressive stance, enhancing conceptual similarity. The only noticeable difference lay in orientation – with Lacoste's crocodile facing right, and Crocodile International's facing left, which was likely to be perceived as insignificant by the average consumer. Overall, similarities in shape, silhouette, and key design elements of the rival logos, especially when coupled with their application to identical products, created a significant likelihood of consumer confusion.

Co-existence Agreement

In its defence, Crocodile International argued that the recitals of the 1983 Co-existence Agreement, stating the parties' overall intention to co-operate globally, meant its applicability stretched beyond the five territories explicitly mentioned therein - Taiwan, Singapore, Indonesia, Malaysia and Brunei.

The court disagreed. Contracts, it stated, must be expressed in precise and unambiguous terms. Territoriality is central to trademark law - a trademark registered in one country does not automatically confer rights to the holder in another, unless explicitly stated through international agreements or treaties. Its interpretation echoed a Partial Arbitral Award dated August 15, 2011, rendered in arbitration proceedings between both parties in Singapore, which also noted that the preamble to the 1983 Agreement could not be construed as a binding obligation of parties to co-exist in jurisdictions beyond the delineated territories. The court highlighted another relevant fact – despite the said Agreement, both parties had persisted in their litigations against one another over the crocodile trademark in other jurisdictions, including China and Myanmar.

Also, the 1985 Letter relied upon by Crocodile International was regarded merely as a general expression of support or non-opposition re Korea, Bangladesh, Pakistan and India. For it to be considered a binding agreement, it ought to have been mutually acknowledged, and clearly delineated the rights of each party. Hence, the Letter was an ineffective basis for arguing a global co-existence intent.

Copyright

When it came to copyright, the crocodile logos of both parties were adjudged independent creations – no inference of copying was possible. Further, the underlying concept of the conflicting works was identical – a graphical representation of a ferocious crocodile in an aggressive stance. Similarities between the two designs, arising from the same underlying idea with limited means of manifestation, invited application of the doctrine of merger, and defeated Lacoste's claim of copyright infringement.

Conclusion

In its order dated August 14, 2024, the Delhi High Court permanently restrained Crocodile International from manufacturing, selling, offering for sale, advertising, or using the disputed logo in any manner that would amount to infringement of Lacoste's registered trademarks. However, no relief was granted on the claim of passing-off absent convincing proof of Lacoste having acquired a substantial reputation in India at the time when Crocodile International began using a similar mark. The judgement is well-reasoned and effectively addresses the several issues that arose as part of the Lacoste v. Crocodile International dispute in India.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.