The substantive law in India governing the recognition and enforcement of patent rights is the Patents Act, 1970. This act has been revised several times and was substantially amended by:

- the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002; and

- the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005.

Patent litigation proceedings governed by the Patents Act are civil court proceedings because the Patents Act provides only for civil remedies for patent infringement.

The procedural laws that govern patent litigation proceedings are:

- the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908;

- the Indian Evidence Act, 1872; and

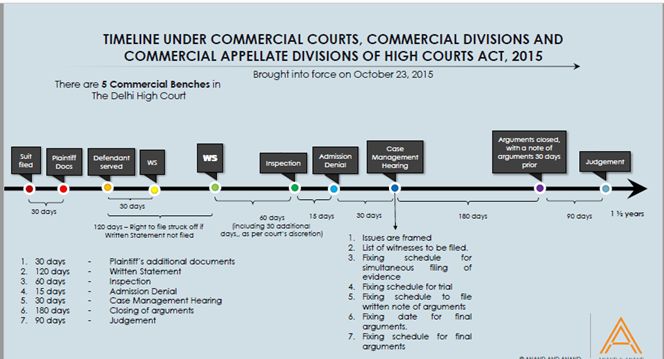

- the Commercial Courts Act, 2015.

The Code of Civil Procedure lays down comprehensive guidelines regarding the procedures that need to be followed by civil courts; while the Indian Evidence Act lays down the rules governing the admissibility of evidence in the Indian courts. The Commercial Courts Act amended the Code of Civil Procedure in relation to commercial disputes; and IP disputes such as patent litigation qualify as commercial disputes under the Commercial Courts Act.

India is a signatory to the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which is relevant to patent litigation. As patent prosecution issues also sometimes arise in patent litigation, it is relevant that the Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property and the Patent Cooperation Treaty also have effect in India.

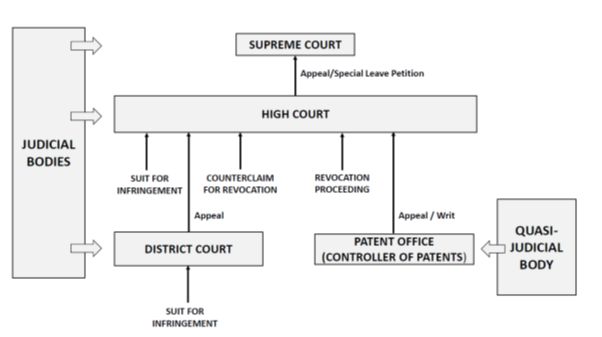

The civil courts and the Indian Patent Office are responsible for interpreting and enforcing the patent laws. The Indian judiciary is essentially a three-tier system, with approximately:

- 600 district courts hearing cases at first instance;

- 24 high courts; and

- the Supreme Court – the court of final appeal – at the apex.

The high court is the highest judicial body in a state and has superintendence over all courts and tribunals situated in the territory in relation to which it exercises jurisdiction.

The district courts generally have unlimited pecuniary jurisdiction. However, the district courts that fall under the jurisdiction of the Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, Shimla and Madras High Courts have limited pecuniary jurisdiction. These high courts can therefore exercise original jurisdiction in patent infringement matters subject to the pecuniary jurisdiction as prescribed under their respective rules. Currently, only five high courts – the high courts of Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, Shimla and Madras – have original jurisdiction and may thus hear patent infringement lawsuits as courts of first instance.

With respect to the agencies that are responsible for interpreting and enforcing the patent laws, in addition to the Indian Patent Office and the civil courts, the IP Appellate Board (IPAB) previously carried out this process. On 30 June 2021, the central government abolished the IPAB. The IPAB served as the first appellate authority for decisions of the controller general of patents. Illustratively, it dealt with:

- revocation proceedings under Section 64 of the Patents Act;

- appeals of orders allowing pre-grant opposition under Section 25(1) of the Patents Act;

- appeals of post-grant opposition orders under Section 25(2) of the Patents Act; and

- various other appeals arising from the stage of prosecution of a patent.

With the abolition of the IPAB, appeals from the patent offices of Kolkata, Chennai, Mumbai, and Delhi now lie with the respective high courts (ie, the Calcutta, Madras, Bombay and Delhi High Courts).

The structure is represented in the following diagram:

Patent litigation commences in the district court; or, where a high court exercises ordinary original civil jurisdiction (ie, acts as a court of first instance), directly in the high court. In practice, it is preferable to institute a patent infringement suit before a high court rather than a district court, due to factors such as:

- the complex nature of IP litigation;

- the availability of fast-track trials; and

- the grant of interim relief.

Most of the IP case law that has developed over the past four decades is from the high courts of Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta and Madras.

Of all high courts, the majority of patent-related actions have been instituted before the Delhi High Court. Further, the Delhi High Court modified its original side rules in 2018, which further streamlined and expedited the procedure for patent litigation proceedings.

Pursuant to the abolition of the IP Appellate Board (IPAB) in 2021, the Delhi High Court has now created an IP Division and notified the Delhi High Court IP Rights Division Rules, 2022. These rules are for matters to be listed before the IP Division of the Delhi High Court and regulate its practice and procedure. Therefore, IP disputes – including patent litigation proceedings – have been assigned to specific benches in the Delhi High Court. These specific benches (there are currently two) exclusively hear IP matters on a day-to-day basis, which has further strengthened the patent enforcement regime in India. An illustrative analysis indicates that the IP Division rendered over 50 decisions pertaining to patent law in just one year (March 2022-March 2023).

In contrast to patent infringement, patent validity is determined by a civil court where:

- the defendant of a lawsuit brings a counterclaim for patent infringement; or

- a third party, in the absence of a lawsuit, independently seeks patent revocation before the relevant authority.

Under the current structure, the issue of validity may be decided as follows:

- Validity and infringement are decided by the same court, which in all probability will be a high court in India. For example, if the infringement suit is brought before the Delhi High Court and a counterclaim is filed by the defendant, validity is also decided by the Delhi High Court.

- Validity is decided by one high court (eg, the Madras High Court, if an application for patent revocation has been filed with the Madras High Court IP Division) and infringement is decided by:

-

- another high court (eg, where a lawsuit has been filed in the Delhi High Court); or

- a district court, if a lawsuit has been filed in a district court and patent revocation has not been sought in that suit.

- In this scenario, to ensure the consistency of decisions, it may be possible for the parties to transfer the matter to one jurisdiction only. This new regime is currently developing and further clarity may emerge on this.

- Validity alone is decided by the relevant high court if no infringement action has been initiated.

Given that an application for revocation is usually filed in patent litigation, or where an application for revocation is filed first and an infringement action is subsequently instituted, the first situation listed above is most common, so the issues of validity and infringement are usually adjudicated in the same forum.

Although the IPAB has now been abolished, while it existed it was not possible for patent litigation to take place before a civil court in which a counterclaim for revocation was brought if a contemporaneous revocation proceeding involving the same patent was pending before the IPAB. In Dr Aloys Wobben v Shri Yogesh Mehra, the Supreme Court held that separate invalidity actions – that is, before the IPAB and in the form of a counterclaim before the high court in an infringement suit – could not be filed and pursued by the same party against the same patent simultaneously. The Supreme Court reversed this decision and held that only the first filed invalidity proceedings could continue unless the parties by consent agreed to continue the later-filed proceedings. Further, the Supreme Court held that:

- where an infringement suit was filed, the only remedy to challenge the patent was through a counterclaim in the suit; and

- a revocation petition filed before the IPAB after the institution of patent litigation was not sustainable in law.

The courts hear and decide patent disputes in India. If the patent litigation is instituted in the high court, it is heard by a single judge. An appeal from the order of the single judge goes to a panel of two judges, known as the division bench.

Forum shopping is not possible in India, as confirmed by the Supreme Court in M/s Chetak Construction Ltd v Om Prakash. A patent holder is the dominus litus of its infringement action and – subject to satisfying all procedural requirements, such as jurisdiction – is entitled to commence patent litigation in the forum of its choice.

A suit for patent infringement may be instituted by the patent holder under the Patents Act, 1970. Section 109 of the Patents Act also permits the exclusive licensee of a patent to institute an action for patent infringement, provided that the patent holder is also impleaded as a co-plaintiff or a defendant.

A patent infringement suit is premised upon the violation of Section 48 of the Patents Act, 1970, which provides that a patent holder or the party instituting the suit may restrain unauthorised third parties from the “act of making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing” the patented product. Where the subject matter of the patent is a process, unauthorised third parties may be restrained from the “act of using the process, and from the act of using, offering for sale, selling or importing for those purposes the product obtained directly by that process in India”.

In addition to the Patents Act, a patent infringement suit must comply with all applicable procedural laws, such as:

- the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908; and

- the Commercial Courts Act.

If the lawsuit is filed in the Delhi High Court, it must also comply with:

- the Delhi High Court Intellectual Property Division Rules, 2022; and

- the Patent Suit Rules, 2022.

Additionally, the relevant jurisdiction of the court in which the lawsuit is instituted must be established (see question 5.4).

No answer submitted for this question.

No answer submitted for this question.

No answer submitted for this question.

Patent infringement is a civil remedy in India and a patent infringement suit is premised on the violation of Section 48 of the Patents Act, 1970, which restrains unauthorised third parties from the “act of making, using, offering for sale, selling or importing” the patented product. Where the subject matter of the patent is a process, unauthorised third parties may be restrained from the “act of using the process, and from the act of using, offering for sale, selling or importing for those purposes the product obtained directly by that process in India”. The export of the patented product/process will constitute patent infringement if it is not covered by Section 107A, which sets out the Bolar exemption in India.

Infringement is a mixed question of law and fact. To prove infringement, it must be shown that the ‘invention’ claimed in the patent has been taken in some way. The Patents Act is silent on what qualifies as ‘infringement’ of a patent. Section 48 affords exclusive rights to the patent holder, its agent and/or a licensee. In ascertaining infringement in a particular case, the focus will be on the nature of the invention and the violation of rights conferred to the patent holder under the Patents Act, because it is this violation of rights that will constitute the act of infringement.

In patent litigation, the court assesses both liability and the quantum of monetary remedies in the same trial. If the defendant has brought a counterclaim challenging the validity of the patent in suit, the validity of the patent will also be determined by the court in the same trial.

Literal infringement: The first step requires a determination of the rights conferred by the patent, for which the scope of the claim must be determined. This is ascertained through the construction of the claims. To construe the claims of the patent, these are read in light of the description provided in the patent specification.

The infringement analysis then proceeds to a comparison of the elements of the claim and the elements of the alleged infringer’s product or process. If the alleged infringer’s product or process reads on the claims as construed, infringement is established.

To understand whether a patent has been infringed in a particular case, the court will adhere to the following guidelines:

- Read the description first, then the claims.

- Find out what constitutes prior art.

- Find out what improvement is present over the prior art.

- List the broad features of the improvement (ie, the pith and marrow of the claims).

- Compare these broad features with the defendant’s process or apparatus.

If the defendant’s process or apparatus either is identical to or falls within the scope of the plaintiff’s process or apparatus, there is infringement.

In F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd v Cipla Ltd, the Delhi High Court Division Bench held that a claim over a chemical structure or formula covers within its scope any polymorph of the same chemical structure. The court reasoned that polymorphs differ from each other only in their physical structure but have the same chemical structure, and thus in such case a claim over the chemical structure is infringed. The court held that the ‘chemical structure’ describes the manner in which each molecule of the compound exists. It is not an ‘inter’-molecular concept but an ‘intra’-molecular concept. Irrespective of the polymorphic form of the claimed compound, it has the same chemical structure as that contained in the claim of the patent in suit and is therefore subsumed within the claim of the patent in suit. The division bench also clarified that the fate of a later-filed application for a secondary patent does not negatively affect the scope of protection conferred by the basic patent: in other words, even if the secondary patent is rejected by the Indian Patent Office or abandoned by the patent holder, the primary patent will still be considered to cover within its scope the subject matter of the secondary patent.

Contributory infringement: The concept of contributory infringement has not been incorporated into Indian law, and therefore each person or entity taking part in an act of infringement is individually liable. However, if it deems fit in a particular case, the court may import the common law principles of vicarious liability, abetment and contributory infringement into a patent infringement dispute to impute liability on indirect or contributing infringers.

The doctrine of equivalents has been recognised by the Indian courts. In Ravi Kamal Bali v Kala Tech, the Bombay High Court discussed the doctrine of equivalents in settling a dispute relating to the infringement of a patent for tamperproof locks and seals. This doctrine was also recognised by the Madras High Court in Mariappan v AR Safiullah, in which it was held that a person is guilty of infringement if it makes what is, in substance, the equivalent of the patented article. The doctrine of equivalents was also recently applied in two decisions of the Delhi High Court:

- Sotefin SA v Indraprastha Cancer Society and Research Centre (2022); and

- RX Prism Health Systems Private Limited v Canva Pty Ltd (2023).

No answer submitted for this question.

Before initiating a lawsuit, the patent holder should gather all necessary data – potentially with the assistance of private investigative agencies – and conduct market intelligence to:

- obtain valuable information regarding the defendant, its activities and the infringing goods; and

- determine the various stages of the marketing chain.

Further, there are certain pre-emptive measures that companies may take to secure optimum protection of their patents in India, as follows.

Section 8 compliance: The disclosure requirements under Section 8 of the Patents Act, 1970, direct applicants to:

- disclose periodically all patent applications being prosecuted by them in countries other than India with respect to the same or substantially the same invention; and

- provide the Indian Patent Office with search and examination reports issued in the corresponding foreign applications upon request by a controller of patents.

Non-compliance with Section 8 is grounds for revocation of the patent and is one of two grounds that can render a patent invalid on issues other than the strength of the invention. Non-compliance with Section 8 does not result in automatic revocation of the patent. The court exercises discretion as to whether the patent should be revoked. The court will consider whether the non-compliance was deliberate or intentional. Revocation will follow only if the court forms an opinion that the non-compliance was deliberate.

Further, in Roche, the court held that if the patent holder has “substantially complied” with the requirement of this provision” – that is, if it has disclosed all foreign applications that were reasonably expected to be disclosed by it – the requirements of Section 8 will be satisfied. Elaborating on ‘substantial compliance’, the court observed that as long as the patent holder has complied with the essence or substance of the disclosure requirements set out in Section 8, a failure to comply with some minor or inconsequential aspect will not be viewed as non-compliance. The court further held that the disclosure of a foreign application by an opponent in the opposition proceeding may also suffice for compliance with Section 8.

With respect to Section 8(2) of the Patents Act, 1970 – which relates to the information that a controller of patents may request from patent applicants regarding the processing of a patent application in a country outside India – a notification/circular was issued on 12 March 2018 by the Office of the Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trademarks. The notification made it clear to the examining division of the Indian Patent Office that no such request under Section 8(2) should be made by controllers at the Indian Patent Office as the controllers and examiners have access to the World Intellectual Property Organization’s (WIPO) WIPO CASE and WIPO Digital Access Service. This circular has also been incorporated in the Manual of Patent Office Practice and Procedure. At the same time, should a patent applicant receive objections from the Indian Patent Office under Section 8(2) of the Patents Act, 1970, these can be resolved by including an appropriate disclaimer and providing reference to the notification dated 12 March 2018 in the patent applicant’s first examination report.

Form 27: Statement of Working: Patent holders and licensees must submit details of the extent of commercialisation of the patented invention in the prescribed Form 27. The Patent (Amendment) Rules 2020 introduced a new Form 27 for multiple related patents derived from the same commercial product. The details include, among other things:

- the number of licences granted (if any);

- the revenue/sales generated from sales, licensing or commercialisation of the patented invention; and

- a statement that the public requirement is being met at a reasonable price.

Form 27 must be completed with the utmost care, because it is a statutory requirement.

Working a patent can include, among other things:

- manufacturing the product in India for use in India or for export;

- importing the patented product to India; and

- licensing the patent rights.

Under the Drugs and Cosmetics Act, 1940, packaging an imported product in India amounts to manufacturing in India.

Transparency in company activities:

- Pricing model: Especially in the case of pharmaceutical companies, it is highly recommended that the company have a transparent pricing model.

- Patient access programme: It is also recommended that a pharmaceutical company have a transparent patient access programme (preferably displayed on its website or in any other accessible form).

Early action: Early action is highly recommended in all cases of patent infringement in India. In special cases where there is a reasonable apprehension that infringement is likely to occur, quia timet actions may be instituted before the courts (eg, where an application for manufacturing or marketing approval of the infringer is pending before the drug controller general of India). Many injunctions have been granted ex parte in which the plaintiff has sought an injunction before the launch of the defendant’s product.

Disclosures in pleadings: Suppression of any related facts or information must be avoided and it is recommended to err on the side of over-disclosure before the Indian courts.

Fast-track trial: Parties should request a fast-track trial to expedite the proceedings. This involves outsourcing the recording of evidence to a retired judge so that the evidence can be concluded within a timeframe of six months.

Admissions before other forums: Admissions or statements made by parties before courts in other jurisdictions (eg, the United States, the United Kingdom or the European Union) or admissions or statements made by parties before alternative forums must be coordinated, because they are likely to be used against the party in another country or alternative proceedings. These include statements made in:

- patent applications for related forms (eg, salts, ethers); and

- prosecution history (eg, letters written to the patent office in response to office actions).

Parties must always consider appealing all unfavourable or negative orders so that they do not jeopardise any future actions (eg, if a polymorphic form is rejected).

Interim measures: The interim measures available for patent owners to enforce their rights before a final ruling on merits include the following (see further question 5.5):

- interim injunctions/temporary restraining orders;

- discovery;

- Anton Piller orders for the search and seizure of goods;

- Protem orders for securing interim payment, especially in standard-essential patent (SEP) cases, during pendency of the same; and

- Norwich Pharmacal orders.

The limitation period for filing a patent infringement suit, as specified under the Limitation Act, 1963, is three years from the date of infringement of the patent rights. A cause of action to file a patent infringement lawsuit arises each time a transaction takes place which infringes the patent. Therefore, patent infringement lawsuits are cases in which there is a continuing cause of action, which arises each time that a new infringement of the patent takes place.

Yes, it is common practice to notify the alleged infringer about the initiation of a lawsuit. Prior to listing the suit for hearing before court, the plaintiff must provide proof that the alleged infringer has been served as per the details available with the plaintiff, which are usually obtained from the public domain.

The plaintiff has the option of filing an application for an exemption from service on the alleged infringer. However, this must be justified by strong reasons and should be pursued only in those rare cases where notification of the alleged infringer may cause severe prejudice to the plaintiff.

Notably, even in cases where the alleged infringer has been notified of an infringement claim and has appeared in court to defend its claim on the first date the patent infringement lawsuit is listed, the courts have granted interim relief to the plaintiff, such as an ad interim injunction or recording the alleged infringer’s statement. Therefore, advance notice to the alleged infringer about an infringement claim may not necessarily prejudice the patent holder from obtaining interim relief from the courts.

Procedural requirements: Patent litigation proceedings are civil court proceedings because the Patents Act, 1970 provides only civil remedies for patent infringement. The procedural laws that govern these proceedings are:

- the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908;

- the Indian Evidence Act, 1872; and

- the Commercial Courts Act, 2015, which amended the Code of Civil Procedure for commercial disputes, including patent litigation proceedings.

The Code of Civil Procedure, as amended by the Commercial Courts Act, lays down comprehensive guidelines regarding the procedures to be followed by the civil courts; while the Indian Evidence Act lays down the rules governing the admissibility of evidence in the Indian courts. In those high courts that have established an IP Division pursuant to the abolition of the IP Appellate Board (IPAB), patent litigation proceedings are also regulated by the relevant IP Rights Division Rules. For instance, proceedings before the IP Division of the Delhi High Court are governed by the Delhi High Court Intellectual Property Rights Division Rules, 2022, which regulate its practice and procedure. The Patent Rules, 2003 (as amended in 2021) establish the procedure for the Indian Patent Office.

Jurisdiction: For a civil court to assume jurisdiction in a patent infringement matter, the following principles must be independently satisfied:

- Subject-matter jurisdiction: A patent infringement suit cannot be instituted in any court below a district court. Thus, only district courts and certain High Courts (Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta, Shimla and Madras) have original jurisdiction to entertain a patent infringement suit.

- Territorial jurisdiction: A court can be said to have territorial jurisdiction to entertain a particular suit only where:

-

- a party to the suit actually and voluntarily resides or carries on business within the territorial jurisdiction of the court; or

- the cause of action (infringement of the patent) arises within its territorial jurisdiction. For a cause of action to arise, it is not necessary for the plaintiff to suffer actual injury (actual infringement of the patent) within the jurisdiction of the court – a plaintiff can bring an action even where it has a fear or apprehension that its patent may be infringed within the territorial jurisdiction of the court. These are called quia timet actions: actions based on apprehended injury. To make a successful quia timet claim, the plaintiff must show that the apprehension of injury is credible. Credibility is determined from the facts and circumstances of each case.

- Pecuniary jurisdiction: Pecuniary limitations of the courts determine the forum in which a proceeding can be filed. District courts generally have unlimited pecuniary jurisdiction. However, the district courts that come under the jurisdiction of the Delhi, Bombay, Calcutta and Madras High Courts have limited pecuniary jurisdiction. For instance, to file an action before the Delhi High Court, the plaintiff must satisfy the pecuniary jurisdiction of INR 20 million.

Representation: Representation is not compulsory in patent litigation. An aggrieved person can prosecute the litigation proceedings itself. Otherwise, the aggrieved person may be represented by:

- an advocate enrolled with the Bar Council of India or the relevant bar association in proceedings before a court; or

- a registered patent agent in proceedings before the Indian Patent Office.

Since 2010, law graduates who wish to be enrolled have also been required to pass the All-India Bar Examination conducted by the Bar Council of India.

Under the law, in order to be a patent agent, a person was previously required to:

- have a science or a technical degree; and

- have passed an examination conducted by the Indian Patent Office.

However, in SP Chockalingam v Controller of Patents (WP 8472/2006), the Madras High Court held that Indian lawyers can be patent agents under the Patents Act without passing the patent agent exam. Further, the Madras High Court held that lawyers with a science, engineering or technology background will automatically become patent agents without any requirement to pass the patent agent exam. In Anvita Singh v Union of India, the Delhi High Court Division Bench struck down the minimum-mark scoring in the oral part of the patent agent exam.

Substantive requirements: The substantive law in India governing the recognition and enforcement of patent rights is the Patents Act. This act has been revised several times and was substantially amended by:

- the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2002; and

- the Patents (Amendment) Act, 2005.

The 2005 amendment brought the Patents Act into line with the Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, which introduced the product patent regime for pharmaceutical substances.

Patentability:

Patentable subject matter: Patentability is governed by the statutory definition of an ‘invention’. The act defines an ‘invention’ as a new product or process involving an inventive step and capable of industrial application.

The act further defines ‘inventive step’ as a feature of an invention that involves a technical advancement compared with the existing knowledge, has economic significance or both which makes the invention not obvious to a person skilled in the art.

The act specifically excludes:

- inventions that are frivolous or contrary to well-established laws;

- inventions:

-

- whose primary or intended use or commercial exploitation would be contrary to public policy or morality; or

- that would cause serious prejudice to human, animal or plant life or health, or to the environment;

- the mere discovery of a scientific principle, the formulation of an abstract theory or the discovery of any living or non-living substance occurring in nature;

- the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance that does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance; the mere discovery of any property or new use for a known substance; or the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus, unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant (according to the explanation to this clause, “salts, esters, ethers, polymorphs, metabolites, pure form, particle size, isomers, mixture of isomers, complexes, combinations and other derivatives and of known substances shall be considered to be the same substance, unless they differ significantly in properties with regard to efficacy”);

- substances obtained by a mere admixture resulting only in the aggregation of properties of the components thereof and processes for producing such substances;

- the mere arrangement or rearrangement or duplication of devices, each functioning independently of one another in a known way;

- agricultural or horticultural methods;

- processes for:

-

- the medical, surgical, curative, prophylactic, diagnostic, therapeutic or other treatment of human beings; or

- the similar treatment of animals to keep them free of disease or to increase their economic value or that of their products;

- plants or animals in whole or any part thereof, other than microorganisms, but including seeds, varieties and species, and essentially biological processes for the production or propagation of plants and animals;

- mathematical or business methods, computer programs per se and algorithms;

- literary, dramatic, musical or artistic works and all other aesthetic creations, including cinematographic works and television productions;

- mere schemes, rules or methods of performing mental acts or methods of playing games;

- presentations of information;

- topographies of integrated circuits;

- inventions that effectively constitute traditional knowledge or an aggregation or duplication of known properties of traditionally known component or components; and

- inventions relating to atomic energy.

The Delhi High Court has clarified that Section 3 of the Patents Act lays down a threshold for patent eligibility and if the subject matter falls within the scope of Section 3, an analysis under Section 2(1)(j) need not be used because it will be rejected at the threshold.

In Novartis AG v Union of India, the Supreme Court held that Section 3 of the act unites in one place two different types of provisions:

- provisions declaring that certain things shall not be deemed to be ‘inventions’; and

- provisions stating that, although they result from an invention, certain things still may not be granted a patent due to other considerations.

Further, the Supreme Court held that Section 3(d) (which concerns the mere discovery of a new form of a known substance that does not result in the enhancement of the known efficacy of that substance; the mere discovery of any property or new use for a known substance; or the mere use of a known process, machine or apparatus, unless such known process results in a new product or employs at least one new reactant) sets up a second tier of qualifying standards for chemical substances/pharmaceutical products in order to leave the door open for true and genuine inventions, while seeking to prevent any attempts at repetitive patenting or extension of patent terms on spurious grounds. Further, the court held that the term ‘efficacy’ in Section 3(d) refers to therapeutic efficacy, thereby implying that the patent applicant must demonstrate that the new form of a known substance results in an enhancement of therapeutic efficacy in order to be entitled to a patent. To prove an enhancement of therapeutic efficacy, the patent applicant must rely on properties of a drug substance which involve interaction with the target site. The mere change in form inherent in the new form cannot qualify as an enhancement of efficacy.

The Delhi High Court Division Bench has further explained the intent behind this provision, stating that although it recognises incremental innovations in pharmaceutical patents and in no way relates to the concept of ‘evergreening’ or patent extension, it also captures the legislative understanding that incremental steps may sometimes be so small that the resultant product is no different from the original.

In Ferid Allani v Union of India, the Delhi High Court clarified the law relating to software patents by interpreting Section 3(k) of the Patents Act – the patent eligibility provision that relates to computer programs. The Delhi High Court traced the legislative intent from the Report of the Joint Committee on the Patents (Second Amendment) Bill 1999 (the amendment which introduced Section 3(k)) and held that computer programs ‘per se’ are excluded from patentability. Elaborating further, the court held that the words ‘per se’ were incorporated to ensure that patents are not refused for genuine inventions that are developed based on computer programs. The court held that in the modern age, when so many inventions relating to artificial intelligence and blockchain technologies are based on computer programs, it would be regressive to consider that all inventions relating to computers are not eligible for patents. The court held that as long as an invention demonstrates ‘technical effect’ or ‘technical contribution’, the prohibition set out in Section 3(k) will not apply and the subject matter will be patent eligible; although the invention will still have to satisfy the requirements of novelty, inventive step and industrial application. In this writ petition, by laying down these contours, the Delhi High Court remanded the patent application back to the Indian Patent Office for reconsideration.

Subsequently, the Indian Patent Office rejected the patent application once again on the grounds that Section 3(k) was applicable. An appeal was brought before IPAB, which issued a decision on 20 July 2020 (Ferid Allani v Assistant Controller of Patents and Designs) laying down the law with respect to the interpretation of Section 3(k) of the Patents Act. Allowing the patent application and granting the patent, the IPAB provided the following illustrative list of factors that can be used to show technical effect:

- higher speed;

- reduced hard disk access time;

- more economic use of memory;

- more efficient data compression techniques;

- improved user interface;

- better control of a robotic arm; or

- improved reception or transmission of a radio signal.

Ferid Allani is now regularly invoked in cases pertaining to patents relating to computer software, to provide better clarity as to which patents ought to be granted.

Selection inventions are not explicit mentioned in the Patents Act but are recognised as being patentable under the Indian Patents Act, provided that they fulfil the tests of novelty, inventiveness and industrial applicability. The term ‘selection invention’ applies to patents that identify one group of chemical compounds selected from a larger group of compounds described in a prior patent. The existence of selection inventions is alluded to in Section 3(d) and Sections 88(3) and 91(1) of the act. In Farbewerke Hoechst & Bruning Corp v Unichem Laboratories (‘FH&B v Unichem’), the Bombay High Court held that even in instances in which an invention consists of the production of further members of a known series whose useful attributes have already been described or predicted, it may possess sufficient inventive subject matter to support a valid patent, provided that the somewhat stringent conditions prescribed by Judge Maugham in IG Farbenindustrie AG’s Patent as essential to the validity of a selection patent are satisfied. In other words:

- the selection must be based on some substantial advantage gained or some substantial disadvantage avoided;

- substantially all selected members of the known series or family of substances must necessarily possess the advantage in question; and

- this advantage must be fairly peculiar to the selected group.

Industrial applicability: For an invention to be patentable under the Patents Act, it should be capable of industrial application – in other words, it should be capable of being made or used in an industry. In FH&B v Unichem, the Bombay High Court held that in the absence of any promise in the specification that a definite degree of advantage would result from the use of the invention, the amount of utility required to support a patent is very small. The court went on to say that:

- the invention as described need not be commercially useful, unless the specification promises that it will be; and

- it is sufficient that the invention should, by reason of the features that distinguish it from earlier proposals, be of some use to the public.

The Delhi High Court Division Bench decided the question of industrial applicability in Merck Sharpe and Dohme v Glenmark Pharmaceuticals. The objection raised was that the claimed compound, sitagliptin, did not have industrial applicability because the commercial product used a salt form of sitagliptin rather than a sitagliptin base. The court rejected the argument, holding that if the function of the compound is disclosed and that function is useful in the medical industry, it is industrially applicable. This will be the case even if the compound is not commercially successful.

Similarly, in F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd v Cipla Ltd, the court:

- made a distinction between commercial utility and patent utility; and

- recognised that at the time of the invention, the compound may not be commercially the most viable for immediate marketing.

Novelty: Although the term ‘novelty’ is not specifically defined under the Patents Act, the act does define a ‘new invention’ as an invention or technology that has not been anticipated by publication in any document or used in India or elsewhere in the world before the date of filing of the patent application. In other words, the subject matter has not fallen in the public domain and does not constitute part of the state of the art. Prior public knowledge of the alleged invention will disqualify the grant of a patent. This prior public knowledge may come from word of mouth or published books or other media. The Indian Patent Office examines an application for a patent for anticipation under Section 13 of the act. Anticipation under the Patents Act is by way of prior publication in a document anywhere in the world and by prior claiming. If the prior publication is contained in a document, it may not be necessary that members of the public should have actually read the document; it is sufficient that the document is easily accessible to the public.

For the ground of anticipation to succeed, it is essential that all claim elements or limitations must be found in a single prior art document. It is for this reason that the ground of anticipation normally fails in most cases and the focus shifts to inventive step.

In Novartis AG v Controller General of Patents, Designs and Trademarks, the IPAB held as follows:

- A generic disclosure cannot defeat the novelty of a specific claim – if there is a generic disclosure of an invention in a document, the document cannot be used to invalidate a specific claim for the purposes of novelty;

- Patent term extension documents cannot be used to determine the novelty of a subsequent patent; and

- If a particular aspect was covered in a document but not disclosed in that document, the document cannot be considered for an invalidity analysis.

Further, in Novartis AG v Natco Pharma Limited, the Delhi High Court interpreted Section 64(1)(a) of the Patents Act, 1970, which deals with anticipation by prior claiming. The court held that Section 64(1)(a):

would apply only where the extent to which an innovation is claimed in the complete specification of the patent under challenge is the same as the extent to which it is claimed in the prior art, on which the challenger places reliance. The claim whose validity is being challenged, as it appears in the patent, must be identical to the claim in the prior art, or of co-equal extent and amplitude.

When analysing whether a patent is anticipated by a previous publication under Section 13 of the Patents Act, the inquiry should focus on whether, on the date of filing of the patent applicant’s complete specification, there was prior art published in India or elsewhere.

Chapter VI of the Patents Act provides that under certain circumstances, in spite of prior public disclosure of the invention, the invention will not be found to be anticipated. For example, there will be no anticipation if:

- the invention was displayed in an industrial exhibition; and

- the application is filed within 12 months of the opening of the exhibition.

Another exception is where the invention is described in a paper read by the inventor before a scholarly group. In this instance, the grace period is also 12 months from reading.

Non-obviousness/inventive step: ‘Inventive step’ is defined under the Patents Act as a feature of an invention that involves a technical advance compared with the existing knowledge, has economic significance or both, rendering the invention non-obvious to a person skilled in the art.

To be patentable, an improvement on something known before or a combination of different matters already known should:

- be something more than a mere workshop improvement; and

- independently satisfy the test of invention or ‘inventive step’.

To be patentable, the improvement or combination must produce:

- a new result;

- a new article; or

- a better or cheaper article than before.

The mere collection of more than one claim element, or things not involving the exercise of any inventive faculty, does not qualify for the grant of a patent.

In F Hoffman-La Roche Ltd v Cipla Ltd, the Division Bench articulated criteria for an inventive step enquiry. It held that to determine obviousness/lack of inventive step, the following inquiries must be conducted:

- Identify an ordinary person skilled in the art.

- Identify the inventive concept embodied in the patent.

- Impute to a normal skilled but unimaginative ordinary person skilled in the art what was common general knowledge in the art at the priority date.

- Identify the differences, if any, between the matter cited and the alleged invention and ascertain whether the differences are ordinary application of law or involve various different steps requiring multiple theoretical and practical applications.

- Decide whether those differences, viewed in the knowledge of the alleged invention, constituted steps that would have been obvious to the ordinary person skilled in the art and rule out a hindsight approach.

In Merck Sharpe & Dohme v Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, a single judge of the Delhi High Court granted the first permanent injunction in a patent infringement suit under the Patents Act. The court affirmed the validity of the patent for the compound sitagliptin and found that the patent was both novel and non-obvious. The court rejected the hindsight approach adopted by the defendant’s witness and held that in an obviousness inquiry, mere comparison of chemical structure is not sufficient. The court found that picking up parts of chemical structures from different patents and clubbing them to form the claimed compound is not an appropriate approach for reaching a finding of obviousness, as this appeared to have been done based on hindsight – in other words, based on knowledge of the claimed compound that the inventors did not have at the priority date of the patent.

Similarly, in Bristol Myers Squibb Co v JD Joshi and Novartis AG v Cipla Ltd, the Delhi High Court held that a challenger to the validity of a patent must raise a credible challenge to the validity of a patent to avoid the grant of an interim/preliminary injunction. The mere statement of prior art in pleadings is not sufficient to raise a credible challenge; the same must be established through cogent evidence.

Supporting disclosure: The claims must be fairly based on the matter disclosed in the specification. Every complete specification of a patent must disclose the best method of performing the invention that is known to the applicant (for grant of a patent) and for which it is entitled to claim protection. For a patent to be valid, the patent must not merely disclose a novel product or process, but also be ‘enabling’ – in other words, it must disclose a method for working the invention. If the disclosure of the patent is found to fall short of being enabling, the patent can be held invalid on the grounds of insufficiency. The objection of insufficiency will fail, however, if the directions in the specification are sufficient to enable a person having reasonable knowledge and skill to make the invention, although some trial and error may be required.

The Delhi High Court Division Bench decided the question of insufficiency in Merck Sharpe & Dohme v Glenmark Pharmaceuticals. This question was raised in the context of a Markush claim: the defendant alleged that the plaintiff’s Markush claim was overbroad in scope and was thus invalid because it was ‘insufficient’. The court rejected the objection and held that the specific compound was disclosed with sufficient clarity and precision. The court noted that the question of whether a patent sufficiently discloses a particular combination (out of the billions it claims to cover) may arise on a case-by-case basis, on considering whether the combination has a different use, action, function, chemical structure or value to take it out of the coverage of the Markush formula.

Types of patents available: The current patent system in India deals only with invention patents. India does not have a utility model patent.

Territorial scope of a patent: Patent rights are territorial in nature because a patent is a creation of statute and the rights of a patent holder granted under the statute are enforceable only within the territory in which the statute applies. Indian patents have force throughout the territory of India. Indian courts can only enforce patents granted in India and cannot enforce a foreign patent within India unless a corresponding Indian patent for the same invention is available.

Furthermore, an Indian court cannot grant relief with respect to patent infringements committed outside its territory, because the Indian courts can exercise jurisdiction only in relation to the cause of action arising within their jurisdiction. However, in Interdigital Technology Corporation v Xiaomi Corporation, in a first-of-its-kind order, the Delhi High Court granted an injunction preventing the defendants from pursuing its anti-suit action in Wuhan, China. The plaintiffs before the Delhi High Court moved an application seeking to restrain the defendants from enforcing an order that had been passed by the Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court on 23 September 2020. The Wuhan Intermediate People’s Court passed an anti-suit injunction order restraining the plaintiffs before the Delhi High Court from instituting and enforcing a suit for infringement before any forums. The Delhi High Court held that, to the extent that a defendant in a lawsuit seeks to restrain the plaintiff to a lawsuit, the courts can interfere if any decision passed by any forum resulted in substantial injustice to the rights of an Indian citizen in India. The court further held that its decision did not violate the principle of comity of courts because this principle does not apply where any order of a foreign court:

- violates Indian public policy;

- breaches customary international law; or

- results in manifest justice.

The court also found that:

- it is not open to any court to pass an order prohibiting a court in another country from exercising jurisdiction that has been lawfully vested in it; and

- the pendency of proceedings in a foreign jurisdiction did not prevent the court from passing the present order.

Claim construction: Claim construction is discussed in greater detail in question 8.

Patent infringement complaint: A complaint in India is referred to as a ‘plaint’, and the requirements and form are governed by the Code of Civil Procedure, as amended by the Commercial Courts Act, 2015. Specifically, Orders VI and VII of the Code of Civil Procedure, as amended by the Commercial Courts Act, lay down the relevant requirements. These requirements apply to all civil suits, including patent litigation proceedings, and are as follows:

- The pleadings in the plaint must contain a statement in a concise form of the material facts which the party pleading relies for its claim, but not the evidence by which they are to be proved. The ‘pleadings’ are the statements/averments that are made in the plaint. The Code of Civil Procedure specifies that a Plaint must be a statement of facts.

- Every pleading must, where necessary, be divided into paragraphs, numbered consecutively, with each allegation contained in a separate paragraph, as far as is convenient.

- In commercial disputes, such as patent litigation proceedings, pleadings are verified by way of an affidavit and a statement of truth. These are signed by any person on behalf of the plaintiff who is acquainted with the facts and circumstances of the case and has been duly authorised by the plaintiff. This individual is referred to as an ‘authorised representative’. If a pleading is not verified in this manner, a party may not be allowed to rely on such pleading as evidence.

- The plaint must contain the following particulars:

-

- the name of the court in which the suit is brought;

- the name, description and place of residence of the plaintiff;

- the name, description and place of residence of the defendant, as far as these can be ascertained;

- the facts constituting the cause of action and when it arose;

- the facts showing that the court has jurisdiction;

- the relief which the plaintiff claims, which should be specifically claimed; and

- a statement of the value of the subject matter of the suit for the purposes of jurisdiction and court fees, as far as the case admits.

Moreover, pursuant to the Tribunal Reforms Act, 2021, on 24 February 2022, the Delhi High Court notified the High Court of Delhi Rules Governing Patent Suits, 2022 under:

- Section 7 of the Delhi High Court, 1966;

- Section 129 of the Code of Civil Procedure; and

- the Patents Act.

These rules govern the procedures of civil suits and patent suits filed before the Delhi High Court.

The rules lay down 15 requirements which a plaint in a patent infringement action should include to the extent possible, as follows:

- a brief background of the technology, the technical details, a description of the suit patent and the invention covered by the suit patent, and a description of the plaintiff’s product or process (if any);

- ownership details of the patent and details of the patent granted in India, including the date of the application;

- any other patent applications filed, withdrawn or pending, including divisional applications relating to or emanating from the patent, or a priority application in India;

- a brief summary of international corresponding applications/patents and the grant thereof, including details of worldwide protection for the invention;

- a brief prosecution history of the patent;

- details of any challenge to the patent and the outcome thereof;

- details of any orders passed by any Indian or international court or tribunal upholding or rejecting the validity of the suit patent or a patent for the same or substantially the same invention;

- information as to whether the patent is being enforced for the first time in India;

- precise claims versus product (or process) chart mapping or, in the case of SEPs, a claim chart mapping through standards;

- an infringement analysis, explained with reference to the granted claims in the specification, with:

-

- details of the allegedly infringing product or process;

- the manner in which the alleged infringement is being conducted, including a description of the defendant’s process, if available;

- details of any licences granted in relation to the patent or the plaintiff’s relevant portfolio, to the extent feasible;

- a summary of the relevant correspondence entered into between the parties relating to the patent or the plaintiff’s relevant portfolio;

- a preliminary list of experts, if any;

- details of sales by the plaintiff and/or a statement of royalties received in relation to the patent or the plaintiff’s relevant portfolio, where feasible and if relied upon the plaintiff; and

- the remedies/relief which the plaintiff seeks and quantification of damages (this could be based on estimated loss, whether due to lost profits and/or royalties incurred by the plaintiff), interest and costs.

Interim remedies are available in patent litigation in India. Interim remedies may be obtained from the court by filing an appropriate interim remedy application along with the main suit for patent infringement. Usually, at the time of institution of the suit, in addition to filing a complaint along with the documents that it seeks to rely upon, a patent litigant may also file an application seeking interim remedies from the court. However, applications for interim remedies can be filed at any time during the lawsuit, prior to the final decision.

The various forms that these interim remedies may take, and how they are obtained, are outlined below.

Interim injunctions/temporary restraining orders: The principles guiding the grant of a preliminary injunction are laid down in Order XXXIX, Rules 1 and 2 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. A court has discretion to grant or refuse such relief. A plaintiff can seek preliminary relief in the form of a preliminary injunction if it satisfies the following conditions:

- The plaintiff’s patent is prima facie valid;

- There is, prima facie, an infringement on the part of the defendant;

- The balance of convenience is in favour of the grant of an injunction; and

- The plaintiff would suffer an irreparable injury if an injunction were denied.

Interim royalties: The relief awarded by interim injunction may also take different forms. For example, in the Phillips DVD cases and the Ericsson cases, which concerned SEPs, the court awarded interim royalties to the plaintiffs. In other words, the defendants were required to pay a royalty to the plaintiffs at a rate determined by the court. Illustratively, these interim royalty rates can be based on the royalty rates fixed between a comparable willing licensee and the plaintiff. The Delhi High Court passed various orders in which interim arrangements were set up, such as payment of INR 100 per device and INR 34 per infringing device to the court. These orders were issued in the Ericsson and Dolby cases.

Moreover, in the Philips DVD cases, the Delhi High Court laid down the factors relevant for determining royalties with respect to SEPs. Relying on Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organization v CISCO Systems, Inc, Fed Cir Dec 3 (2015), the court stated that the following may be considered in determining the royalty:

- the parties’ informal negotiations with respect to the end product;

- fair, reasonable and non-discriminatory terms; and

- the incremental benefit derived from the invention.

The court further held that the Indian patent was an ‘essential patent’ for DVD technology, since the patent holder had proven that the corresponding US and European patents had been declared as essential for DVD technology (“DVD-Rom, Video Disk and DVD play backs”). An appeal is pending but the order has not been stayed.

PROTEM orders: The Delhi High Court also passed a series of orders in SEP cases under which PROTEM securities were provided by way of bank guarantee and land lien. For instance, in Koninklijke Philips NV v Xiaomi Inc, the court directed Xiaomi to maintain INR 10 billion in its bank accounts. Thereafter, Xiaomi agreed to file a bank guarantee for the same amount. In Koninklijke Philips NV v Vivo Mobile Communication Co Ltd, the court directed Vivo not to create any encumbrances or third-party rights on its immovable property and superstructure.

General framework for the grant of interim injunction: To obtain an interim injunction, it is not sufficient merely to have an issued patent. The court will consider all aspects, including the strength of the patent holder’s case and the strength of the defence. If the plaintiff has not pursued a preliminary injunction, the Delhi High Court has directed many patent matters to proceed to a fast-track trial.

In Merck Sharpe and Dohme v Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, the Supreme Court directed the parties:

- to complete the trial proceeding within 45 days; and

- to conduct cross-examination on a day-to-day basis.

The evidence, cross-examination and oral arguments were completed in a record time of three months.

A court may grant an ex parte preliminary injunction where it appears that the object of granting the injunction would be defeated by giving notice to the defendant. The Delhi High Court has granted ex parte interim injunctions in cases where the defendant’s product was yet to be launched in the market (quia timet actions).

In granting a preliminary injunction in favour of the plaintiff in Easai Co Ltd v Satish Reddy, the court held that the defendants had not ‘cleared the way’ prior to seeking marketing approval to produce a generic version of the patented pharmaceutical product. In other words, the defendants did not invoke any invalidity proceedings challenging the patent but chose to seek marketing approval knowing full well that litigation was bound to result. The concept of ‘clearing the way’ developed by the court is significant because it places a burden on the defendant to exercise due diligence and exhibit good faith if it intends to use the subject matter covered by a patent.

In Telefonaktiebolaget LM Ericsson v Mercury Electronics, the Delhi High Court held that the burden of proving invalidity falls squarely falls on the party challenging invalidity, which is required to provide sufficient evidence. Further, the court clarified the decision in Biswanath Prasad Radhey Shyam to the effect that there is no presumption of validity of a patent. The court held that the Biswanath Prasad ruling is limited only to the extent that no liability will be incurred by the central government or any other officer thereof in connection with the grant of a patent.

That said, a preliminary or interim injunction can be denied to the patent holder if there is a credible challenge to the patent by the defendant.

Discovery: Discovery can be by way of interrogatories, delivered with the leave of the court, for the examination of opposite parties. As long as the interrogatories are relevant, they may be allowed. If allowed, the interrogatories must be answered by affidavits. Where a party fails to answer or answers insufficiently, it may be required to answer either by affidavit or by live examination. Additionally, at any time during the pendency of the suit, the court may order the production, on oath, of such documents as are in the possession or power of a party. Where the claimant (ie, the patent holder in an infringement suit) fails to comply with the order of interrogatories, discovery or inspection of documents, the suit is liable to be dismissed for want of prosecution; and if the defendant fails to comply, its defence is liable to be struck out.

Confidentiality clubs: In M Sivamany v Vestergaard Fransen A/S, the issue was whether one party is entitled to seek the production of documents containing confidential or proprietary information of the other party. The court observed that although the claimants were not entitled to unconditional access to the defendants’ confidential or proprietary information, the defendants should not be able to avoid suit if their product was nothing but a copy of the product of the claimant. The court held that to balance the rights of both the parties, a procedure should be adopted that:

- maintains the confidentiality of the documents produced; and

- does not prejudice any of the parties.

With this direction, the court remanded the matter to a single judge to decide the procedure to be followed. The procedure laid down involved the formation of a ‘confidentiality club’, consisting of a few advocates, nominated by each party, who alone accessed the confidential or proprietary information of the defendants. These advocates were bound by confidentiality orders passed by the court and the proceedings in which they were able to access the documents were in camera.

This concept of a ‘confidentiality club’ has now been incorporated into the Delhi High Court Rules, 2018, which regulate the practice and procedure of commercial disputes – including patent litigation proceedings – before the Delhi High Court. Chapter VI, Rule 17 of the Delhi High Court Rules provides that when the parties to a commercial suit wish to rely on documents and/or information that is commercially or otherwise confidential in nature, the court may establish a confidentiality club to ensure that there is limited access to such documents and/or information. Annexure F of the Delhi High Court Rules, 2018 provides an illustrative structure of what the confidentiality club should look like. The court has the freedom to mould the structure/protocol of the club based on the facts and circumstances of each case.

The illustrative protocol of the confidentiality club, as prescribed in Annexure F of the Delhi High Court Rules, 2018, is as follows:

- All documents and/or information that are considered confidential by the court may be filed in a sealed cover to be kept in the safe custody of the registrar general.

- The members of the confidentiality club, who will inspect the confidential documents and/or information, will be nominated by the parties to the dispute. Each party can nominate:

-

- up to three advocates, who must not be and have never been in-house lawyers of either party; and

- up to two external experts.

- The members of the confidentiality club:

-

- can inspect the confidential documents and/or information before the registrar general without making any copies thereof;

- cannot disclose or publish the contents of the confidential documents and/or information to anyone else in any manner or by any means or in any legal proceedings; and

- will be bound by the orders of the court.

- After the inspection, the confidential documents and/or information will be resealed and kept in the custody of the registrar general. They will not be available for inspection after disposal of the matter, except to the party that has produced them.

- The court may, at its discretion, permit copies of the confidential documents and/or information to be given to the opposite side after they have been redacted, if this is possible.

- If, during the court proceedings, the confidential documents and/or information are being looked at or the contents are being discussed, only members of the confidentiality club may be present.

In Interdigital Technology Corporation v Xiaomi Corporation and Interdigital VC Holdings Inc v Xiaomi Corporation, the court:

- refused to restrict the constitution of the confidentiality club to external experts and lawyers; and

- held, on the principles of natural justice, that the defendant must receive the documents.

The order was vacated after Interdigital and Xiaomi entered into a settlement, as recently recorded in the Supreme Court.

The concept of confidentiality clubs has also been incorporated into:

- Rule 19 of the Delhi High Court IP Rights Division Rules, 2022; and

- Rule 11 of the High Court of Delhi Rules Governing Patent Suits, 2022.

These rules govern the procedure and practice of the Delhi High Court and provide as follows:

- At any stage of the proceedings, the court may constitute a confidentiality club consisting of lawyers and external and in-house experts, as nominated representatives of the parties, for the preservation and exchange of confidential information before the court, as per the Delhi High Court (Original Side) Rules, 2018.

- The nominated representatives of the parties who are appointed to the club may be persons who are not in charge of, or active in, the day-to-day business operations and management of the respective parties so that integrity of information disclosed can be maintained.

- The court may also redact such information (including documents) as is deems to be confidential. Further, if the redacted pleading is sought to be filed, a non-redacted version of the same may be filed in a sealed cover.

Anton Piller orders: The Indian courts in civil actions grant Anton Piller orders to allow the plaintiff to enter the defendant’s premises to:

- inspect, search and seize, and preserve evidence; and

- prevent the destruction of incriminating evidence before the case comes to trial.

To give effect to such orders, court commissioners are appointed by the court to search and seize infringing goods. Such an order can be passed by the court on an appropriate application made by the plaintiff under Order XXVI read with Order XXXIX, Rule 7 of the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908. Such relief is generally given in copyright and trademark infringement cases. However, in principle, it can also be granted in patent cases.

Norwich Pharmacal orders: There is no precedent of Norwich Pharmacal orders having been applied for and granted in patent litigation actions. However, these orders have been successfully obtained in trademark infringement cases, so it is likely that this trend will also be followed in actions for patent infringement. For instance, in Bristol-Myers Squibb Company v M Adinarayan, the court directed the drug controller general and the drug controller of Uttarakhand to send to the court in a sealed cover the marketing approval and manufacturing licence respectively obtained by the defendant, at the request of the plaintiff, even though these regulatory authorities were not impleaded as parties.

As per Order 25, a sole plaintiff based outside of India with insufficient immovable property within India may be required to furnish a sum as security for the payment of all costs incurred and/or likely to be incurred by any defendant.

Therefore, it is recommended that foreign entities tie up with an Indian company or use a local licensee as co-plaintiff to avoid these costs or even to strengthen their stand on public interest.

Disclosure can be by way of discovery or by way of interrogatories, which are provided for in the Code of Civil Procedure. The grant of such disclosures is at the discretion of the court; the request for disclosure can be opposed on the grounds that it is irrelevant and has no bearing on the suit. To balance the need for disclosure with the need to avoid the disclosure of sensitive information, the courts have come up with the concept of confidentiality clubs (see question 5.5).

The rules on third-party disclosure are similar to those on general disclosure (see questions 5.5 and 6.1). With respect to third-party disclosure, the onus is on the party seeking such disclosure to justify:

- why this is necessary for the patent infringement action; and

- why the third party was not included in the lawsuit in the first instance.

Attorney-client privilege, as it is known in India, is covered by Sections 126 and 129 of the Indian Evidence Act, 1872.

Section 126 provides that no barrister, pleader, attorney or vakil is at any time permitted, without the client’s express consent, to disclose any communication made in the course of and for the purpose of employment by or on behalf of the client. The barrister, pleader, attorney or vakil also cannot disclose:

- the contents or condition of any document with which he or she has become acquainted; or

- any advice given in the course and for the purpose of employment.

The exceptions to this privilege provided in the act are where:

- the communication is for any illegal purpose; or

- any fact is observed which indicates that a crime or fraud has been committed.

Further, Section 129 states that no one may be compelled to disclose to a court any confidential communication between that person and his or her legal professional adviser, except where he or she presents himself or herself as a witness.

Attorney-client privilege is a type of confidence and is grounded in the obligation of confidence which a legal adviser owes to the client. Only the client can waive this privilege and not the legal adviser. Further, privilege is permanent and survives the death of the client. This right is substantive in nature and is not a procedural right. It covers practising advocates under the Advocates Act, 1961.

Evidence is governed by:

- the Code of Civil Procedure, 1908; and

- the Indian Evidence Act.

In patent litigation proceedings, evidence is given by the parties by way of affidavit. The affidavit of evidence that is filed is considered as examination-in-chief of the witness and the witness must prove the documents referred to in the affidavit. The witness is cross-examined after the examination-in-chief is concluded.

If the evidence by way of affidavit contains any confidential information derived from confidential documents and/or information, this will be kept in a sealed cover with the registrar general and will be accessible only to the members of the confidentiality club (see question 5.5). However, the party filing such evidence by way of affidavit must, if so directed by the court, give the opposing part a copy of such affidavit after redacting therefrom the confidential information, only if such redaction is possible and not otherwise.

The recordal of evidence need not necessarily take place in court. The courts are empowered to appoint local commissioners who may record evidence outside the courtroom. Local commissioners are usually retired judges who monitor the evidence stage. In patent litigation, evidence is commonly recorded before a local commissioner. The recordal of evidence can also take place through video conferencing, so the physical attendance of the witness is not necessary. The Delhi High Court regularly records evidence by way of video conference and certain safeguards have been built into the process. Additionally, if a witness is unable to communicate in English, there is an option to appoint a translator.

The evidence stage and the procedures in the Delhi High Court described above are further governed by:

- the Delhi High Court (Original Side) Rules, 2018; and

- the Delhi High Court IP Rights Division Rules, 2022.

The 2018 rules:

- set stringent timelines;

- empower the court commissioner to monitor these timelines;

- permit the appointment of interpreters; and

- allow evidence to be taken outside court.

A local commissioner must also disclose that he or she has no conflict of interest.

To ensure the objective of a fast-track trial, the 2018 rules provide as follows:

- The evidence before the court commissioner will be recorded on a day-to-day basis and must be completed within six months of the date first fixed before the local commissioner.

- If the commissioner feels that the extent of the documents so warrants, exhibit marking of documents can also take place without the presence of the witness.

Further, the 2022 rules provide that if the court believes it is necessary and expedient to do so, it may direct:

- the recordal of evidence through video conference as per the High Court of Delhi Rules for Video Conferencing for Courts 2021;

- the recordal of evidence at any venue outside the court;

- the recordal of evidence by a local commissioner; and

- the use of videography and transcription technology or any other form of recording evidence.

The 2022 rules also provide that expert evidence maybe recorded by resorting to:

- procedures such as ‘hot-tubbing’ as provided for in Rule 6, Chapter XI of the 2018 rules; or

- such other modes as the court deems fit.

Hot-tubbing has yet to be used in patent litigation.

The types of evidence pertain to the types of witnesses that a party can produce in patent litigation. There are no specific rules in this regard. At the same time, parties usually have three witnesses:

- a corporate witness, who provides information on the facts of the dispute;

- a technical witness, who provides evidence on the validity of the patent in cases where the validity of the patent is challenged – which happens in almost all cases; and

- a witness who deposes on infringement, such as in telecommunications patent disputes, in which infringement may be proved by an external expert.

The choice of whether the witness is to be a representative of the plaintiff or an external expert is left to the plaintiff. Further, the number of witnesses that should depose in a matter is also dependent on each party.

Expert evidence is permitted. In Merck Sharpe and Dohme v Glenmark Pharmaceuticals, the court opined that in highly technical matters such as the case before it (which involved chemical compounds in the medical field), the court must rely on the opinions of experts in the field whose testimony is found trustworthy and reliable and supported by documents. The court should not override the view of the technical experts, especially where the judges are not experts in the relevant field.

Patent infringement proceedings are civil suits. The applicable standard of proof is the balance of probabilities.

The burden of proof in the Indian Evidence Act rests with the party that alleges a particular fact. As the plaintiff in a patent infringement proceeding alleges infringement of the patent, the burden of proving infringement rests with on the plaintiff. On the other hand, if the defendant challenges the validity of the patent, the burden of proving its invalidity rests with the defendant.

Therefore, parties lead evidence on issues that have been framed by the court and the burden of proof rests with them. Usually, the plaintiff leads its evidence first. While leading evidence, the plaintiff has the right to reserve its right to lead evidence on these issues, the onus on which is placed upon the defendant.

At the beginning of an infringement action, US courts conduct what is known as a ‘Markman hearing’ to define the scope of the claims or to shed light on certain ambiguous terms used in the claims. Although this is not technically done in India, in practice, most judges will undertake a similar exercise in trying to understand the scope and meaning of the claims, including their terms.

The courts in India construe patent claims in a purposive manner. The claims must be construed to give an effective meaning to each claim, but the specification and the claims must be looked at and construed together.

In F Hoffmann-La Roche Ltd v Cipla Ltd, the Delhi High Court held that:

coverage of a claim, for the purposes of determination and scope of protection under Section 48 of the Patents Act, ha(s) to be determined by claim construction. Claim construction involve(s) reading of the wording of the claim with its enabling disclosures as contained in the complete specifications, as understood by a person skilled in the art, acquainted with the technology in question. A product could be treated as covered by the claim, for the purposes of patent protection, if, on the basis of the wording of the claim read with enabling disclosures in the complete specification, the person skilled in the art would be in a position to work the invention so as to make it available to the public by the expiry of the patent term.

The Delhi High Court also laid down the following principles for claim construction:

- Claims define the territory or scope of protection under Section 10(4)(c) of the Patents Act, 1970.

- There is no limit to the number of claims, except that after 10 claims there is an additional fee per claim (Schedule 1 of the act).

- Claims can be independent or dependent.

- The broad structure of a set of claims is an inverted pyramid, with the broadest at the top and the narrowest at the bottom (Manual of Patents Office – Practice and Procedure).