- within Energy and Natural Resources topic(s)

- within Energy and Natural Resources topic(s)

- within International Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Securities & Investment industries

The Federal Network Agency recently published the awards of offshore tenders for the bid date of 1 August 2024. The three tendered areas (N-9.1, N-9.2 and N-9.3) in the North Sea with a total capacity of 5.5 GW were awarded to the energy producer RWE (N-9.1 and N-9.2) and the asset manager Luxcara (N-9.3). This was already the second round of bidding in 2024.

In the first round (1 June), two sites in the North Sea (with a capacity of 1.5 GW (site N-11.2) and 1 GW (site N-12.3)) were already awarded to a consortium consisting of RWE and Total as well as the energy producer EnBW for a sum of around EUR 3 billion. The wind farms to be built on the tendered areas are scheduled to go into operation between 2029 and 2031. Areas with an installed capacity of 8.8 GW were already put out to tender in 2023. The respective tender volume in 2023 and 2024 almost corresponds to the currently installed offshore wind capacity of 8.5 GW. The figures show that a number of new offshore wind farms will be installed in German waters over the next few years.

What is the current status of offshore wind energy in Germany?

At the end of 2023, 1,566 wind turbines with a total capacity of almost 8.5 GW were installed off the North Sea coast and Baltic Sea coast. In addition, a total of around 3.72 GW of capacity was under construction and scheduled to be commissioned by 2026. From the 2022 to 2024 tendering rounds, a further 8 GW are to be commissioned by the end of 2029 and a further 15.5 GW in 2030 and 2031. For the years 2025 - 2027, the 2023 area development plan for the German North Sea and Baltic Sea also provides for the tendering of further areas with a capacity of 6 GW, which are then to be commissioned in the years 2030 to 2032. From 2028 onwards, areas with a capacity of 2 GW are to be put out to tender each year based on the current draft of the update to the 2023 Area Development Plan.

What are the expansion targets in Germany?

The expansion targets for offshore wind energy are set out in the Offshore Wind Energy Act (WindSeeG). According to this, at least 30 GW of offshore wind capacity is to be installed by 2030, 40 GW by 2035 and a total of at least 70 GW by 2045.

Will the targets for 2030 be achieved?

If existing capacity is added to the capacity that will be put into operation in future according to current planning, the target of 30 GW will be narrowly missed at 29.96 GW. However, further offshore wind farms are to be commissioned in 2031 and 2032, meaning that the target is likely to be reached in the following years.

What is the situation with offshore wind energy outside Germany?

Offshore wind energy does not just play a key role in Germany in terms of energy supply and achieving climate protection targets. In other European countries too, offshore wind energy is a key element in achieving both national and international climate targets and at the same time meeting the growing demand for energy.

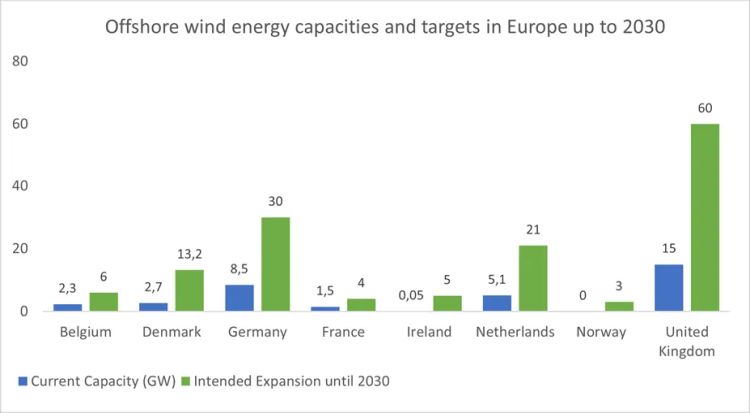

The United Kingdom deserves a mention, as the most important player in the offshore wind energy sector alongside Germany and the largest offshore wind energy producer in Europe with an installed capacity of around 15 GW. The new British government has also committed to quadrupling offshore wind power by 2030 to fully decarbonise electricity generation by 2030. This means that offshore wind power, where the UK is already number one in Europe, is to be increased from 15 to 60 GW. To fully achieve this target, the new government wants to fundamentally revise the UK's approach to planning and building wind farms and the corresponding grid infrastructure.

What are the expansion targets within the European Union?

Offshore wind power also plays an important role at EU level. In November 2020, for example, the EU Commission published a document entitled "An EU strategy to harness the potential of offshore renewable energy for a climate-neutral future" and issued the following (non-binding) expansion targets for EU waters: at least 60 GW of offshore wind energy by 2030 and 300 GW by 2050. By way of illustration, the EU's total installed offshore capacity in 2022 was around 16.3 GW, meaning that achieving the targets for 2030 would mean an increase in capacity of over 250%.

To achieve the expansion targets and support the ramp-up of offshore wind energy in the EU, the EU presented two strategies in October 2023: The "European Wind Energy Action Plan" (COM/2023/669) and the "Communication on delivering on the EU offshore renewable energy ambition" (COM/2023/668). The aim of both strategies is to

- strengthen the network infrastructure and cooperation between the individual Member States,

- adopt measures to speed up authorisation procedures,

- to create guidelines for integrated maritime spatial planning,

- strengthen the resilience of the infrastructure, support research and innovation and

- to accelerate the expansion of supply chains and expertise in Europe. To this end, tendering conditions are to be developed that are not primarily based on price, and European manufacturers are to be protected from non-European competitors who receive preferential treatment in their home countries.

The Commission also called on the Member States to cooperate more closely on offshore wind energy at an early stage.

Expansion in the North Sea/Ostend Declaration

In the spirit of accelerated cooperation, the eight countries bordering the North Sea (Belgium, Denmark, Germany, France, Ireland, the Netherlands, Norway and the United Kingdom) and Luxembourg agreed in April 2023 in the Ostend Declaration, among other things, to massively drive forward the expansion of offshore wind energy in the North Sea and to install 120 GW of capacity in the North Sea by 2030 and 300 GW by 2050. In terms of the envisaged installed capacity, these targets are higher than those of the original EU strategy. The Ostend Declaration's target of installing 120 GW of capacity in the North Sea by 2030 is therefore double the target of 60 GW set by the EU for the EU as a whole.

What are the specific expansion targets in the North Sea?

Looking at the North Sea states mentioned above, it is clear that massive offshore wind farms are to be installed in these countries by 2030 (and beyond). Offshore wind farms with a capacity of around 23.5 GW are to be commissioned by 2030 and further wind farms with a capacity of around 74 GW by 2038 in order to achieve the stated targets (all data is as of November 2023).

Objectives under the Ostend Agreement

The targets are clear and make it clear that offshore wind power will play a key role in all North Sea states to achieve the decarbonisation of energy generation and societies. The targets set for 2030 are immense in comparison to the currently installed capacities and show that offshore wind power is set to boom in the coming years. In some cases, such as in the United Kingdom, the targets agreed in the Ostend Declaration are already outdated and have been replaced by even more ambitious targets (e.g. United Kingdom 60 GW instead of 50 GW). In this respect, it is clear that the North Sea is to become Europe's power plant.

Is it realistic to achieve the targets in the countries bordering the North Sea?

But how does the actual planning and expansion relate to the targets? It is worth taking a look at the tender volumes for offshore wind areas, which provide a good indication of whether the targets are actually being "filled" with areas and projects. The following picture emerges for the individual countries bordering the North Sea:

- Alongside Germany, the United Kingdom is currently the most important player in the offshore wind energy sector and is the largest offshore wind energy producer in Europe with an installed capacity of around 15 GW. Part of the British strategy is to increase offshore wind capacity to 60 GW by 2030. Around 6.4 GW of offshore wind capacity is currently under construction and is due to be completed by the mid-2020s, with a further 7.6 GW of offshore wind capacity about to start construction. A further 51 GW of sites are under development and planning, of which 15 GW are to be commissioned by 2030. This would result in a total installed capacity for 2030 of 44 GW, meaning that the 2030 target would not be met.

- The Netherlands is also planning a massive expansion of offshore wind. Around 5.1 GW of capacity is currently installed in the Netherlands and the aim is to install 21 GW of offshore wind capacity by 2030, although this target was recently postponed to 2032 (however, over 5 GW is to be installed by the end of 2030). In order to achieve this target, it is planned to put up to 17.4 GW of capacity out to tender by 2030, the majority of which is to be commissioned by 2032. If these plans materialise, the Netherlands will reach its expansion target in 2032 (then 22.1 GW of installed capacity).

- Denmark is also focussing heavily on offshore wind energy. This is expected to make a significant contribution to the Danish energy transition. By the end of 2023, around 2.7 GW of offshore wind capacity had already been installed in Denmark. The updated expansion target in the latest draft of the National Energy and Climate Plan envisages a total capacity of 13.2 GW by 2030. The tender volume up to 2030 is up to 10 GW, whereby the last tender is to take place in 2025. The last commissioning is then planned for 2031 and 2.2 GW of capacity is to be commissioned by 2030. The installed capacity in 2030 would then amount to 12.5 GW, meaning that the target for 2030 will probably not be fully achieved.

- There are plans to significantly expand offshore wind energy in France. An initial 4 GW of offshore wind energy is to be installed in French waters by 2030. Currently, the installed capacity in all French waters is 1.5 GW. By 2030, a further 12.5 GW of capacity is to be put out to tender and around 3 GW commissioned, meaning that France should reach its target for 2030 (installed capacity should then amount to 4.3 GW).

- Belgium plans to install 6 GW of offshore wind capacity in its waters by 2030. There are currently 2.3 GW of offshore wind turbines installed and the intention is to tender a further 3.5 GW of capacity by 2030. Of this tender volume, 0.7 GW is to be commissioned by 2030 and the remaining 2.8 GW in 2031. The target for 2030 is therefore not expected to be reached until 2031.

- Ireland also intends to construct large-scale offshore wind farms. Although the installed capacity is currently negligible compared to other countries (0.05 GW), Ireland plans to commission at least 5 GW of capacity by 2030. Ireland intends to put 11.6 GW of capacity out to tender by 2030, of which 4 GW is to be installed by 2031.

- Norway intends to install 3 GW of offshore wind power in national waters by 2030. There is currently one offshore wind farm in Norway with an installed capacity of 88 MW. In order to achieve the set expansion target of 3 GW, Norway plans to put 3 GW of capacity out to tender in 2024, which is to be installed by 2030, meaning that Norway should achieve the set targets.

What does the expansion of wind energy in the Baltic Sea look like?

There are also initiatives for cooperation in the Baltic Sea. For example, the eight European Baltic Sea countries (Denmark, Germany, Estonia, Finland, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland and Sweden) have committed to increasing offshore wind power in the Baltic Sea from around 3.1 GW today to 19.6 GW by 2030. Poland plans to install 6 GW by 2030 (currently 0 GW). Finland plans to commission its first large wind farm by 2026-2027 and another by 2028. In Sweden, 15 GW of projects are currently being applied for approval. Some could be connected to the grid before 2030. Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania also want to commission their first offshore wind farms before 2030. In Germany, 1.3 GW and in Denmark up to 7.9 GW are planned to be added in the Baltic Sea by 2030. The expansion of offshore wind energy is also being massively increased in the Baltic Sea, albeit not to the same extent as in the North Sea.

Conclusion/Outlook

The goals are clear, but achieving the targets set for 2030 does not seem realistic in all countries.

Irrespective of whether the targets set for 2030 are actually achieved or not, the current tender volumes in the individual countries show that the targets are being backed up with actual projects and concrete planning, meaning that a significant expansion of offshore wind energy is imminent. In this respect, the next important and complex steps to realise the projects technically and logistically are almost underway.

In addition to the already known specific offshore risks such as bad weather, ground risks or interface issues between the individual players as well as current risks such as disruptions in global supply chains due to wars, sanctions and protectionism, the realisation of the projects and the achievement of the targets will also depend on whether new challenges can be solved. Such new challenges, which are already becoming apparent in current projects and are likely to become even more acute with the massive expansion envisaged in future projects, are primarily bottlenecks in the availability of suitable installation vessels and the necessary port infrastructure, the required skilled workers and the consideration of non-price-related criteria such as the decarbonisation of offshore expansion, compliance with minimum ecological and social criteria and the use of environmentally friendly foundation technologies as early as the tendering stage of projects in order to ensure fair competition in the supply chain and thus also strengthen a European supply chain.

Originally published 23 September 2024

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.