- within Compliance, Wealth Management and Tax topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

- in Canada

- with readers working within the Healthcare industries

- Forest Offset Credits: A Cornerstone of Sustainable Development on Aboriginal Lands

- Carbon Market Watch

- After Copenhagen, the Focus Shifts to the Provinces

- Carbon Capture and Storage Update

- Carbon Round Up

-

- International

- British Columbia

- Saskatchewan

- Manitoba

- Ontario

- Quebec

- USA

Forest Offset Credits: A Cornerstone of Sustainable

Development on Aboriginal Lands

By: Scott A. Smith and Mark L. Madras

Part I: The social, economic, and environmental benefits of carbon offset projects

Since the arrival of Europeans in North America, the use and management of natural resources on Aboriginal lands have been a frequent source of controversy and dispute. These disputes have centred around issues of ownership and control, but they have also often pitted economic interests – including those of Aboriginal communities themselves – against protection of the environment and of traditional sites.

The emergence of a new commodity – carbon credits – offers the intriguing possibility of engaging in economic development that also benefits the environment. The generation and sale of carbon credits creates wealth through environmental protection. As such, carbon offset projects offer a promising and still largely untapped source of economic development for Aboriginal communities.

As the world grapples with climate change and global warming, increased environmental and economic value is being attributed to carbon offset projects. Carbon credits can be generated by non-regulated entities that undertake "offset projects" which either remove greenhouse gas ("GHG") emissions from the atmosphere and store them in natural reservoirs, or reduce or avoid GHG emissions altogether. Quantified emission reductions achieved by carbon offset projects can be converted into carbon credits recognized by regulatory cap-and-trade systems, voluntary carbon markets, or both. These credits can then be sold within a cap-and-trade system or on voluntary carbon markets. Regulated entities that purchase the offset credits may apply them to offset emissions in order to meet emissions targets. Non-regulated entities may purchase offset credits or offset projects to speculate, for reasons of corporate social responsibility, to offer carbon neutral products or to retire the credits for conservation purposes.

The types of offset projects that qualify for mandatory and voluntary carbon markets vary substantially. Recognized carbon offset projects include forestry projects (afforestation/ reforestation, forest management, avoided deforestation), agricultural projects (soil carbon sequestration and manure management), waste management projects (landfill gas recovery), renewable energy projects and energy efficiency projects. Most emerging domestic and regional carbon markets -- including Canada's proposed offset system, the Western Climate Initiative, the Alberta carbon offset system, and Ontario's proposed system which is currently under discussion -- propose to include afforestation and other carbon sequestration projects as permissible offset activities. In addition, such projects can be used to create credits for the voluntary markets. Rigorous analysis during the early stages of project planning and development is, however, required to ensure that a carbon offset project is eligible and meets the specific requirements of any given market and, in particular, to determine the eventual liquidity of the credits.

Forest offset projects are cost-effective ways to generate carbon credits either by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and storing it in plant biomass, or by preventing the release of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. For example, afforestation projects involve planting trees on previously non-forested lands to create new forests or woodlots. New trees act as a carbon "sink" by absorbing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere. During the process of photosynthesis, trees convert atmospheric carbon dioxide and water into oxygen and organic compounds (carbohydrates) using energy from sunlight. The organic compounds (containing carbon) are then incorporated into plant tissue (biomass) where the carbon is stored or "sequestered". New forests or woodlots created by afforestation projects act as carbon storage reservoirs which reduce the concentration of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. Quantified emission reductions achieved by afforestation projects can then be converted into carbon credits which can be sold on carbon markets.

Forest carbon offset projects may be of particular interest to Aboriginal communities because they achieve a variety of social, economic, and ecological benefits in addition to sequestering carbon dioxide. New or better managed forests or woodlots provide numerous ecological services including new habitat for wildlife, links between previously isolated biological communities, protection of ground and surface water quality and quantity, erosion control, as well as economic and recreational benefits.

Forest carbon offset projects therefore represent significant opportunities to engage in sustainable development because they provide a source of revenue to create, protect, and manage forests to sequester carbon dioxide in a way that achieves a myriad of additional social and ecological benefits.

Part II – Legal ownership of carbon credits generated by projects situate Aboriginal land

A key concern arising from many carbon offset projects is who owns the carbon credits generated by the project.

Clear legal ownership of carbon credits created by offset projects should be established at the onset of project development as it is a required element for the registration of projects with third party registry and standards. Disputes about ownership may delay certification of the carbon credits until the dispute is resolved, and they will ultimately reduce profits by increasing the per unit cost of the carbon credits as a result of legal fees and other costs associated with settling ownership disputes. Moreover, delineating who retains the rights to carbon credits, or how rights will be apportioned, provides a degree of cost and revenue certainty which is essential to project planning, financing, and development.

Clearly identifying ownership of, and delineating long-term legal liability for, carbon credits generated by offset projects is even more essential in the case of biological sink projects such as afforestation projects where tree harvesting, natural disasters, and pest outbreaks may reverse carbon sequestration by emitting previously stored carbon dioxide into the atmosphere. A carbon deficit will arise when credits have already been issued for the carbon dioxide that was originally sequestered in the forested area but which is subsequently released as a result of such activities. Carbon markets may manage this risk by allowing only temporary credits to be issued, by requiring project proponents to buy insurance to compensate for reversals, by holding back a given percentage of credits in a reserve pool, by requiring proponents who do not own the land on which the offset project is implemented on to obtain a conservation easement over the land, and ultimately, by holding project proponents liable for carbon deficits. Project proponents must therefore delineate and clearly apportion or assign the liability attached to this risk where ownership of the carbon credits generated by the carbon offset project is uncertain or apportioned between persons.

In the absence of contracts or other legal agreements that establish ownership of carbon credits generated by offset projects, disputes over ownership may arise where projects are:

- implemented on Crown land;

- implemented by the lessee and not the land owner;

- implemented using a proprietary technology to achieve emission reductions;

- implemented by a proponent that is not the same person as the downstream user; and

- implemented on lands subject to Aboriginal claims.

Project proponents, Aboriginal communities and regulatory bodies should be aware of the opportunities and risks involved with developing carbon offset projects on land subject to Aboriginal claims.

Aboriginal communities may be able to claim ownership of carbon credits through: (a) their direct interest in the land, or (b) their Aboriginal and treaty rights.

Aboriginal communities may be able to claim ownership of carbon credits generated on land: (1) held under Aboriginal title, (2) on reserves, and (3) subject to settled land claim agreements. In other circumstances, such as unsettled land claims and claims to Aboriginal rights over traditional territory, an ownership interest in carbon offset credits may still be asserted, but may require negotiation, revenue-sharing or even litigation to determine the existence or extent of that interest.

Aboriginal communities' ability to claim ownership of carbon credits generated by offset projects on land held pursuant to Aboriginal title or subject to Aboriginal land claims derives from the bundle of rights attached to Aboriginal title. The rights that flow from Aboriginal title include the right to exclusively use and occupy the land, the right to determine how the land will be used subject to the limits inherent to Aboriginal title, and the right to, or ownership of, natural resources on the land.

It follows from the Supreme Court's dicta in Delgamuukw v. British Columbia, the leading case in Canadian law on Aboriginal title, that Aboriginal title holders own carbon credits generated by offset projects that they develop and implement on land held under Aboriginal title. Carbon offset projects therefore provide an important way that Aboriginal communities can use land held pursuant to Aboriginal title to buttress their efforts to develop sustainably.

Second, Aboriginal interests in reserve lands also provide a sufficient basis for Aboriginal communities to claim the benefits flowing from ownership of carbon credits generated by offset projects implemented on reserves. Aboriginal interests in reserve lands often include surface and mineral rights. It is therefore likely that such interests also include the right to the benefits flowing from carbon offset credits generated on reserve lands.

Legal title over reserve lands is held by the Crown "for the use and benefit of the respective band". Rights to carbon credits generated on lands in reserves will therefore be held by the Crown in trust for the benefit of First Nations communities. Project proponents (including First Nations communities), regulatory bodies, and purchasers of carbon credits generated by offset projects implemented on reserves will need to ensure that the requirements for granting an interest in reserve lands prescribed by the Indian Act are complied with.

Furthermore, the Supreme Court's holding in Blueberry River Indian Band v. Canada suggests that the Crown may be under a fiduciary duty to retain the rights to carbon credits for the benefits of Aboriginal communities when it sells or leases surrendered reserve lands in the absence of a clear mandate from a band to sell the rights.

Third, Aboriginal communities may also be able to claim ownership of carbon credits through the rights and interests in land established by settled land claim agreements. For example, the Nisga'a Final Agreement between the Nisga'a First Nation, British Columbia, and Canada provides that the Nisga'a Nation owns Nisga'a Lands in fee simple, and further clarifies that the Nisga'a Nation owns all forest resources on Nisga'a Lands. The Nisga'a Nation will therefore own carbon credits generated by afforestation or avoided deforestation projects that it implements on Nisga'a Lands.

The situation is not as clear, however, in the case of asserted but not yet recognized claims to Aboriginal title. Such claims by their very nature call into question legal ownership of the land, and correspondingly, who is entitled to the bundle of rights attached to that legal ownership. Aboriginal rights, including Aboriginal title, predate Crown sovereignty in Canada and therefore act as a burden on the Crown's underlying title. Some commentators suggest that the content of the Crown or a private land owner's title is whatever interest remains after the Aboriginal right(s) that burdens the land has been subtracted. Complex disputes about ownership of carbon credits may therefore arise when project proponents implement carbon offset projects on lands subject to Aboriginal land claims.

The outcome of such disputes cannot be predicted and, in any event, will normally take many years – even decades – to be determined. Nevertheless. in many cases Aboriginal communities may be entitled to participate in land use management decisions and to share in the economic benefits generated by carbon offset projects undertaken on claimed land.

These rights flow from the Crown's obligation to consult, and potentially accommodate, Aboriginal peoples.

In the leading case of Haida Nation v. British Columbia (Minister of Forests), the Supreme Court of Canada recognized that the Crown (i.e. the government – both federal and provincial) has a constitutional duty to consult with Aboriginal communities where claimed Aboriginal rights or treaty rights may be affected by Crown decisions. While the Crown ultimately remains legally responsible for fulfilling this duty, it may (and often does) delegate procedural aspects of consultation to project proponents.

The duty arises when the Crown "has knowledge, real or constructive, of the potential existence of the Aboriginal right or title and contemplates conduct that might adversely affect it."

In the context of carbon offset projects that generate carbon credits for provincial or federal cap-and-trade systems, the Crown's duty to consult Aboriginal people will likely be engaged when the regulatory body contemplates approving and registering a project that will be implemented on claimed land in its carbon-offset program. It may also be engaged when the provincial or federal decision-maker contemplates issuing carbon credits for emissions reductions achieved by the project.

For both mandatory and voluntary markets, the duty to consult, and where appropriate, accommodate Aboriginal peoples may arise in the early planning and development stages for carbon offset projects on Crown land subject to Aboriginal claims.

The content of the duty will be proportional to a preliminary assessment of the strength of the case supporting the existence of the right or title, and to the seriousness of the potentially adverse effect on the right or title claimed. The content of the duty to consult can best be understood as a spectrum of obligations that vary with the circumstances. At one end of the spectrum, the Crown's duty may be limited to giving notice, disclosing information, and discussing any issues raised in response to the notice. At the other end of the spectrum, deep consultation aimed at finding a satisfactory interim solution will be required.

Crown consultation may give rise to a requirement to accommodate Aboriginal claimants by minimizing infringement of the asserted right(s) when a strong prima facie case exists for the claim, and the consequences of the government's proposed decision may adversely affect Aboriginal claimants in a significant way.

At a minimum, therefore, the Crown must consult with Aboriginal claimants about carbon offset projects on Crown land or for projects that will generate carbon credits for provincially or federally regulated cap-and-trade systems when the projects are situate on land claimed by Aboriginal peoples. When a strong prima facie case exists for the asserted Aboriginal claims, the Crown will likely need to meaningfully accommodate Aboriginal claimants. In so doing, the Crown will need to reasonably balance Aboriginal concerns about the potential impact of the decision on the right or title with other societal interests. The outcome of this balancing process may require the Crown to involve Aboriginal communities in decision-making processes related to the project, and to provide Aboriginal claimants with fair economic compensation for the carbon credits that are generated on the claimed land.

The Crown, and not the project proponent, will be liable for failing to accommodate Aboriginal claimants when the circumstances require. If the Crown fails to satisfy its duty to consult, and where appropriate, to accommodate Aboriginal rights claimants, a court of competent jurisdiction may set aside the decision that was made in breach of the duty. This may involve, in a regulated system, quashing approval for the carbon offset project, or quashing the decision to issue carbon credits to the project proponent. The case law suggests, however, that courts may be reluctant to grant this remedy when quashing the regulatory decision prejudices the rights of private parties. The court may make an order suspending the implementation of the Crown's decision or approval to allow for proper consultation to occur. The Court may also issue a declaration the Crown has breached its duty to consult, or provide other declaratory relief.

It will therefore be in the shared interests of project proponents, Aboriginal communities, and the Crown to contemplate entering into Impact and Benefit Agreements or other such agreements which clearly define decision-making rights and responsibilities, ownership of carbon credits, and liability for those credits prior to undertaking carbon offset projects on land subject to Aboriginal claims. Such agreements should clarify how the Crown or its delegate will consult with, and where appropriate, accommodate, Aboriginal rights claimants.

A more controversial issue is whether Aboriginal communities, through Aboriginal and treaty rights, may claim ownership of carbon credits generated on traditional territories that are not reserves, lands subject to settled land claim agreements, or lands held pursuant to Aboriginal title.

Aboriginal communities may face certain barriers to claiming ownership of carbon offset credits generated on traditional territory through Aboriginal rights. To qualify as an Aboriginal right, an activity "must be an element of a practice, custom or tradition integral to the distinctive culture of the aboriginal group claiming the right" that existed prior to European contact.

The key issues will therefore be how the right being claimed is characterized and ultimately, whether a court will accept a broadly characterized right that captures the benefits of carbon offset credits generated on traditional land.

It is unlikely that the activity of generating and selling carbon offset credits itself can be qualified as the modern evolution of an integral pre-contact Aboriginal practice based on the current jurisprudence on Aboriginal rights.

Aboriginal communities may, however, be able to assert that ownership of, or a right to some of the benefits generated by, carbon offset credits is ancillary to a right to environmental stewardship and management. The key here is to establish that current environmental management practices are rooted in pre-contact practices. Aboriginal communities that exercise such a right may then be able to claim the benefits of carbon offset credits that are generated by such environmental management practices.

From a political perspective, the carbon "crop" arguably represents an unforeseen windfall for all involved. Where Aboriginal groups have an interest, whatever its nature, it can reasonably be argued that this should entitle them, at minimum, to a share of the windfall. Non-Aboriginal society largely profited from the industrialization that is the primary cause of climate change; it would be ironic if non-Aboriginal society reaped the financial benefits of trying to reverse climate change to the exclusion of Aboriginal communities.

Treaty rights also provide a means for Aboriginal communities to claim ownership of carbon offset credits generated on traditional territories. In Marshall v. Canada, the Supreme Court laid down the guiding principles of treaty interpretation, which include the requirement that Canadian courts must "update treaty rights to provide for their modern exercise". Determining the modern content of treaty rights consists of establishing which practices are reasonably incidental to the core treaty right in its modern context. This involves distilling the core of the treaty right to see how it might be developed in the modern context.

In R. v. Beattie, the Federal Court provided an expansive reading of the right to agricultural assistance in Treaty 11, holding that the core of the treaty right is the "development of a capacity for self-sufficiency based on the use of the land base". The Court held that the modern form of this right could involve expanding the definition of agriculture "to include other renewable resources whose cultivation could be the basis for self-sufficiency".

This interpretation suggests that treaty rights to hunt, fish, and to receive agricultural assistance may merely be species of a core right to self-sufficiency based on the sustainable use of treaty lands. This modern understanding of treaty rights reflects the historical context and purpose of such treaties: to ensure peaceful relations between nations partly founded on the strategy of fostering economic self-sufficiency of Aboriginal communities.

Using treaty lands to generate and sell carbon offset credits may therefore potentially qualify as an analogous species of activity that makes up the modern treaty right to self-sufficiency based on the sustainable use of treaty land.

Alternatively, sustainable forest management and conservation practices may be incidental to an aboriginal or treaty right to hunt. Aboriginal communities could assert ownership of, or a right to some of the benefits derived from, carbon offset credits generated by such practices in the manner described above.

Delineating ownership of carbon offset credits generated on lands subject to Aboriginal claims must now be at the forefront of negotiators' minds when they sit down to negotiate Aboriginal land claims. Aboriginal communities currently making or negotiating claims should now systematically seek to reserve the rights to carbon credits generated on claimed land as part of the land claim negotiations process.

Similarly, Aboriginal communities should also clearly define, and seek to retain, the right to carbon credits generated by projects implemented by others on Aboriginal lands. This process will necessarily involve assessing which entities may also have a claim to some or all of the benefits of such carbon offset projects.

For example, afforestation projects implemented in traditional territories located on Crown land will give rise to legal uncertainties over who is entitled to the carbon offset credits generated by such projects. Aboriginal communities will likely need to consult and work jointly with others who may hold title or other rights to these lands. Those entities may include the provincial and federal governments, as well as natural resource companies (forestry, mining) that have licences or other interests in traditional territories.

Disputes over ownership of carbon credits generated by offset projects involving forest management practices may arise when they are implemented by forestry or other companies that have a licence or other interest on Aboriginal land or on traditional lands on which Aboriginal communities have an Aboriginal or treaty right to engage in environmental stewardship and management. It will therefore be important for Aboriginal communities and project proponents to identify and delineate who will retain the rights to carbon credits in those circumstances.

Conclusion

Carbon offset projects represent an important means by which Aboriginal communities can engage in self-sufficient sustainable development. The sale of carbon offset credits generated on Aboriginal lands can potentially provide Aboriginal communities with an important source of revenue and a means of economic development that protects and enhances the natural environment of their traditional territories.

It can also potentially provide Canadian industries, such as oil sands operators, with an ethical means to meet more stringent carbon emissions reduction targets that will likely be forthcoming in the near future.

Carbon offset projects implemented in Canada by Aboriginal communities on their traditional territories therefore have the potential to serve as a model for sustainable development both here and abroad.

Carbon Market Watch

By: Douglas W. Clarke

MCX Activity

Our comments regarding the MCX are unchanged since our last report. Activity remains depressed on this market due to the uncertainty that the underlying element of the forward contracts (Canadian federal GHG emission reduction units) will be available for delivery on the contract expiration dates.

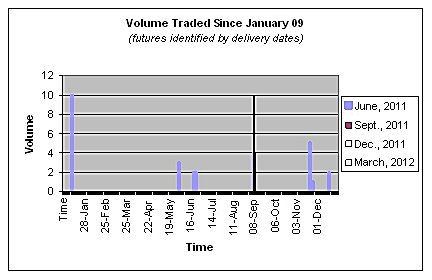

The updated table above shows the trading volume since January 1, 2009 for the four (4) contracts that are currently traded. Until such time as the federal government begins to create more certainty with respect to the timing of the coming into force of GHG regulation in Canada, there is little reason to expect any significant pick-up in the transaction volumes handled by the MCX.

We continue to believe that a short term solution for this lack of activity would be for the MCX to diversify its product offering into the voluntary market, however, this has not happened yet.

OTC Market

Activity in the North American voluntary carbon market picked up in the third quarter of 2009 after significant decline in the early part of 2009. This renewed activity was reflected in a reported increase in the average price of voluntary carbon units. Increased volume was delivered on the back of trading activity in Climate Action Reserve reduction units, which were seen as a pre-compliance play as a result of text of the Waxman-Markey Bill that made it through the US House of Representatives.1

International reports of the success of reverse auctions in which buyers indicate the type of VER they wish to purchase and the sellers bid against each other on price, tend to indicate that the market in the second half of 2009 was a buyers' market; our experience has been that this trend is likely wrong as a broad statement. While it is true that the Climex platform traded around a quarter of a million VERs in September and November, our experience has been that projects with a social component were in demand and that there was increasing demand during the third quarter for certain projects in particular.2

As the financial crisis eases, we expect the voluntary market to be robust in 2010 as it becomes better understood by a wider section of the financial sector. We believe that buying carbon credits, be it for reasons of corporate social responsibility, carbon neutrality or pre-compliance, is now firmly embedded in the culture of many businesses and that this activity, to the extent there are available funds, will continue to be carried out by an increasing number of businesses.

After Copenhagen, the Focus Shifts to the

Provinces

By: Mark Madras and Ian Richler

The ambiguous and noncommittal outcome of the Copenhagen climate change talks, and Canada's statements leading to and at Copenhagen, add further uncertainty to Canada's climate change strategy. The "Turning the Corner" plan (released in March 2008) is of doubtful relevance today. Instead, the federal strategy will likely mirror whatever develops in the US Congress, where attention may shift back to climate change now that the intense legislative battle over health care reform has ended.

Twelve years after the Kyoto Protocol was adopted, Canada still has no federal regulations limiting industrial GHG emissions, and has now more or less officially adopted a wait and see policy where Washington gets to make the first move. The federal government's admitted lack of willingness to put in place domestic GHG regulations before the US regime takes shape likely means that the focus in the next year will be on the provinces, and in particular those that are members of the Western Climate Initiative (Ontario, Quebec, Manitoba and BC), which is poised to implement a cap and trade system in 2012. In the absence of a federal regime, the key question may well be whether these provinces and their US state counterparts have the courage of their stated convictions and regulate on a provincial-state basis.

The WCI began in 2007 as a partnership of five western US states and has since expanded to include two more states and the four provinces (several other US and Mexican states, as well as Saskatchewan, have "observer" status but are not full partners). The WCI is now well positioned for implementation, with design documents and concepts well advanced. If it does proceed, the key elements industry in the WCI provinces should expect are:

- the first phase of the cap and trade program, covering electricity generation and large industrial and commercial emitters, would come into force on January 1, 2012; the program would be expanded in 2015 to cover other emissions including from transportation, residential and smaller industrial sources (the WCI states that almost 90% of GHG emissions would be covered once the second phase is implemented);

- a mix of GHG allowances – some distributed gratis and some by auction;

- an offset system allowing non-capped entities to earn carbon credits for voluntary emissions reduction measures;

- trading of allowances and offsets;

- interchangeability of allowances and offsets with those from other WCI provinces and states;

- some international linkages (e.g. with the Clean Development Mechanism under the Kyoto Protocol) on a limited basis;

- the partnership as a whole has set a regional target of a 15% GHG reduction from 2005 levels by 2020.

Copenhagen may have dealt a blow to hopes for an integrated global cap and trade system based on common compliance-based requirements for credits. The focus may now shift, at least in the short term, to subnational and regional systems.

Copenhagen goes to show how difficult it is to create a GHG limiting regime across jurisdictions of disparate economic and political realities. The same holds true within Canada. Any federal climate change plan would have to strike a delicate balance between competing provincial concerns.

The future of climate change regulation may lie with building blocks of less ambitious climate protection systems in smaller units of like minded and like situated jurisdictions. It may be that, when it comes to GHG strategy, Ontario has more in common with California or Oregon than it does with Alberta.

Carbon Capture and Storage Update

By: Patricia Leeson

The Province of Alberta is targeting a 200 megatonne reduction in greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by 2050. Studies by Integrated CO2 Network indicate that, through a phased build-up of CCS, there is the potential to reduce CO2 emissions in Alberta by up to 35 megatonnes per year by the early to mid 2020's. This represents approximately 5% of all of Canada's current emissions. Alberta is home to a unique geological formation, known the Western Canadian Sedimentary Basin (WCSB), which it can use to effect large scale CCS. Although the WCSB is the source of significant amounts of CO2 emissions as a function of hydrocarbon development, it also contains natural reservoirs in relative proximity with vast potential to store CO2.

In 2007 the Climate Change Emissions and Management Act and related regulations were enacted, introducing intensity based reduction targets for installations emitting more than 100,000 tonnes of CO2e. Compliance options include purchasing offsets from offset projects located in Alberta and contributing $15/tonne to the Climate Change Emissions Management Fund.

This cap and trade system is only a bridging mechanism until such time as Alberta can deploy CCS technology as this is the long term climate change strategy for the Province. Although conservation, energy efficiency and the greening of energy production are part of the Alberta government's long term strategy, CCS is intended to provide 70% of GHG emission reductions.

In the spring of 2008, the Alberta government created the Alberta Carbon Capture & Storage Development Council with the mandate to provide recommendations, through comprehensive reports, to facilitate the immediate, medium and long-term implementation of CCS in Alberta.

In July 2008, the Alberta government announced the creation of a separate fund that would provide $2 billion for CCS projects over 5 years. This money has now been fully committed to four projects.

- Coal – In situ gasification project (Swan Hills Synfuels): This project will produce synthetic gas from an unmineable coal bed near Swan Hills to be used in the generation of clean electricity from a combined cycle power generator. The project will also capture a projected 1.3 million tonnes/year of CO2, which will be used for enhanced oil recovery (EOR).

- Pipeline – Alberta Carbon Trunk line: This pipeline will be constructed for the transportation of CO2 from Agrium Redwater (and later from the oilsand bitumen upgrader) to depleting oil fields near Red Deer. It is designed to carry 40,00 tonnes CO2/day – 14 million tonnes/year. The intended use is EOR. Over time other CO2 producers will be able to connect to the pipeline.

- Storage – Quest project (Shell, Chevron and Marathon Oilsands): This project will capture and store 1.2 million tonnes of CO2/year from the Scottford Upgrader. CO2 will be injected and stored 2300 meters below the surface.

- Coal – Retrofit of a coal fired electricity generation plant (Trans Alta -Keephills 3): CO2 capture from this project will be used for EOR or stored.

The Alberta Government will distribute 40% of the dedicated monies during design & construction, 20% on commercial operation and 40% over 10 years as CO2 is captured and stored.

Challenges Ahead

- CCS infrastructure development requires an ongoing collaborative long-term approach between industry and government. There is a need for additional funding from government to support CCS projects beyond the first wave.

- There will be a need for the provincial and federal levels of government to work together to set a harmonized policy and regulatory framework to facilitate an integrated economic model for CCS.

- Capture costs are high (currently estimated at between $50 and $225/tonne) and exceed the price that EOR operators will pay for CO2. New or improved lower cost capture technologies need to be developed and implemented.

- Finally, there is a need for regulatory and policy clarity regarding GHG reduction targets and the mandatory adoption of CCS technology for new projects as well as greater regulatory certainty in relation to the rules for building environmentally appropriate capture, transportation, and injection facilities and long-term storage liabilities.

Carbon Round Up

International

By: Douglas W. Clarke

The COP 15 meeting in Copenhagen came to a close with no new comprehensive multilateral accord having been reached; however, a draft agreement was proposed by a limited number of states led by the US and China. The draft accord, referred to as the "Copenhagen Accord", was not adopted by the Council of the Parties, which did however "take note" of its existence. Opposition to the accord came from developing countries which objected, inter alia, to the backroom style in which the agreement was reached, without their input.

Under the accord Annex I countries (the developed world) will commit to individual or joint emissions targets for 2020. Non-Annex I countries (the developing world), for their part, will have to implement mitigation actions.

Annex I countries will have to publish their emission targets in by January 2010 and communicate their progress toward achieving their goals every two years. Non-Annex I countries will have to publish their proposed mitigation actions by January 2010 and communicate their progress toward achieving their goals every 2 years as well. The actions of Non-Annex I countries will not be subject to external verification but they agree to use internationally agreed standards in their reporting. Mitigation actions by Non-Annex I countries seeking international support will however be subject to international measurement, reporting and verification in accordance with guidelines adopted by the COP. Such supported actions will be listed in the accord along with the technology, finance or other support granted, presumably by Annex I countries.

On reduced emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, which looked liked it might be the object of an agreement during the COP 15 meetings, the accord states that there should be the immediate establishment of a mechanism for moving capital from developed countries to developing ones to incentivize the reduction of emissions from deforestation and forest degradation and to enhance the removal of GHGs by forests. In the short term, USD 30 billion dollars will be provided between 2010 and 2012 for climate change mitigation and adaptation increasing to USD 100 billion by 2020. These projects will be supported through the Copenhagen Green Climate Fund, which is to be established.

Technology development and transfer will take place on a country to country basis though a "Technology Mechanism". This is in contrast to the existing Clean Development Mechanism, which is project based.

It is still too early to tell what the implications of this change might be for the carbon offset project industry that has grown up in the CDM. We suspect that in the short term at least, there will be substantial pressure put on national governments to maintain the project based international offset system.

British Columbia

By: Peter D. Fairey

British Columbia's cap and trade system took an important step closer to implementation on November 25, 2009 when the detailed Reporting Regulation (the "Regulation") of BC's Greenhouse Gas Reductions (Cap and Trade) Act (the "Act"), together with key sections of the Act were brought into force by Order-in-Council. The Regulation becomes effective January 1, 2010 and requires operations that emit more than 10,000 metric tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (CO2e) per year to report their greenhouse gas ("GHG") emissions to the BC Ministry of Environment. The types of facilities and activities covered by the Act and the attribution of emissions are detailed in the schedules to the Regulation. The Act and the Regulation require that reporting operators submit an annual emissions report by March 31 of the following year. Amongst other things, an emissions report must include facility data broken down by activity (e.g. petroleum refining and electronics manufacturing), emission sources (e.g. from above ground storage tanks, equipment leaks, and combustion of purge gas) and the GHG types emitted. Although the Regulation imposes reporting requirements beginning on January 1, 2010, reporting operators who emitted more than 20,000 metric tonnes of CO2e in any year from 2006 to 2009 must include emission information for each such year in their first emissions report. Operations that emit more than 25,000 metric tonnes of CO2e are required to verify their reported emissions by way of concurrently filed (except in 2010 and 2011 when a five month grace is given) independent third party verification statements. The Regulation stipulates that acceptable third party verifiers must be persons accredited by the Standards Council of Canada or another member of the International Accreditation Forum, in accordance with ISO 14065, or, if the report is completed on or before December 31, 2012, by a person accredited by the California Air Resources Board.

In addition to the Regulation, notable sections of the Act were brought in force including Part 8 – Offences and Penalties. This Part provides for fines and penalties to be imposed against persons contravening the Act and the Regulation, such as the emission reporting requirements discussed above.

The BC Ministry of Environment is presently developing additional guidance and information material to support implementation and understanding of the detailed Regulation. A Methodology Manual, Verification Manual, Emissions Estimation and other useful information may be found on the Ministry website at: http://www.env.gov.bc.ca/epd/codes/ggrcta/reporting-regulation/index.htm (www.env.gov.bc.ca/epd/codes/ggrcta/reporting-regulation/index.htm)

Saskatchewan

By: Michael Garellek

On December 1, 2009, an amended version of The Management and Reduction of Greenhouse Gases Act (the "Saskatchewan Act") was re-introduced to the Assembly as Bill No. 126 (previously Bill No. 95). The two major amendments were as follows:

- Performance agreements. These agreements are permitted to be set up between regulated emitters and the government, and potentially with non-regulated entities, to account for reductions of greenhouse gas emissions in sectors that are not currently covered by the Saskatchewan Act. Regulations will determine the circumstances in which, and the purposes for which, the government may enter into performance agreements.

- The Saskatchewan Act incorporates an environmental code, to establish standards and guidelines as part of what the government refers to as a results-based regulatory system. The contents of the code will be defined by regulation.

Manitoba

By: Michael Garellek

In mid-November 2009, the government of Manitoba published two regulations under The Climate Change and Emissions Reductions Act (the "Manitoba Act").

- The Prescribed Landfills Regulation entered into force on November 21, 2009 and it defines a "prescribed landfill", which is subject to the Manitoba Act, as having greater than or equal to 750,000 tonnes of waste.

- The Coal-Fired Emergency Operations Regulation establishes the conditions under which Manitoba Hydro may use coal to generate power. This regulation will enter into force on January 1, 2010.

At the Copenhagen Climate Conference Premier Greg Selinger announced that Manitoba is committed to moving forward with legislation enabling the creation of a cap-and-trade system to reduce greenhouse gases in the province and that Manitoba will hold pubic consultations in 2010 on the form that such a system will take.

Ontario

By: Neil McCormick

On December 1, 2009, Ontario's Greenhouse Gas Emissions Reporting Regulation (O. Reg. 452/09) (the "Regulation") came into force. Under the Regulation, industrial facilities in Ontario that release 25,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent ("CO2e") will be required to report their emissions data to the government of Ontario on an annual basis. The government of Ontario estimates that between 200-300 facilities will be subject to the Regulation's reporting requirements, including facilities that generate greenhouse gases from the following sources: aluminum production, cement manufacturing, copper production, electricity generation, iron/steel manufacturing, lead production, petroleum refining, pulp and paper manufacturing and zinc production.

The first annual reporting period under the Regulation will begin on January 1, 2010, with the emissions report for the 2010 period due on or before June 1, 2011. The Regulation specifies the contents of the emissions report and along with an accompanying guideline, provides rules for quantifying CO2e emissions. Third party verification of emissions reports according to ISO requirements will be phased-in for the 2011 reporting period and will continue thereafter. Although not subject to the Regulation, smaller emitters (e.g. facilities emitting between 10,000 and 25,000 tonnes of CO2e) will be encouraged to report their emissions under the Regulation on a voluntary basis under an outreach program to be developed by the Ministry of the Environment.

The purpose of the Regulation is to facilitate the development of a cap-and-trade system in Ontario, with linkages to other jurisdictions in North America. To that end, the Government of Ontario has pledged to continue to work with the federal government, other provincial governments, and its Western Climate Initiative partners to harmonize greenhouse gas reporting requirements and methods.

Quebec

By: Douglas W. Clarke

On November 23, 2009, after hearings before the commission on transportation and the environment, Quebec adopted a GHG emission reduction target of 20% below 1990 levels by 2020. In adopting the target, Quebec reiterated its commitment to moving forward with the development of a regional cap and trade system under the umbrella of the WCI.

This announcement was followed by the announcement on December 29, 2009, of the coming into effect in mid January 2010 of California emissions standards for light vehicles in Quebec, making it the first Canadian province to bring these standards into effect. As 40% of Quebec's GHG emissions are caused by transportation, reducing emissions in this sector is a key strategic area for the provincial government.

USA

By: Douglas W. Clarke

In September, the US Senate unveiled its version of cap and trade draft legislation, which, although it calls for deeper short term GHG emission reductions than the House of Representative's Waxman-Markey bill, is in fact quite similar to the House bill which passed during the summer.

The Senate bill, known as the Kerry-Boxer bill, seeks reductions in US emissions of 20% below 2005 levels by 2020 (Waxman-Markey has a 17% target) and 83% below 2005 levels by 2050 (the same as Waxman-Markey).

The legislation seeks to put in place a national cap and trade system that would only apply to large emitters that account for around 75% of US GHG emissions. The bill allows emitters to use offsets to meet their compliance targets as is the case with Waxman-Markey. However, unlike Waxman-Markey, of the 2 billion offsets that will be allowed for compliance, 75% may come from domestic projects, while only 25% may come from international projects. This number was split equally in Waxman-Markey.

More recently, Democratic Senator John Kerry, one of the Senate bill's original sponsors, Republican Lindsey Graham and Independent Joe Lieberman, who have been working together to draft a bill that has the bipartisan support thought to be required to get the 60 votes necessary to pass the Senate, released a "framework" document which proposed certain amendment to the Senate bill.

The document, which was attached to a letter send to President Obama, indicated that the 2020 GHG emission reduction target is reeled back to the same level as Waxman-Markey and the 2050 reduction target is reduced to 80% of 2005 levels. More importantly perhaps, the document contains comfort language around coal, nuclear energy and domestic drilling for oil. Indications perhaps that in the end, US legislation may be a sort of potpourri, in which everyone gets something they like, with a side of pork.

Footnotes

1"VER Market Upturn Underway" available online at http://www.carbonpositive.net/viewarticle.aspx?articleID=1680 (www.carbonpositive.net/viewarticle.aspx?articleID=1680)

2 "Cash cows : Cleaning up in California greenhouse-gas emissions" available online at http://www.financialpost.com/story.html?id=2366113 (www.financialpost.com/story.html?id=2366113)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.