- within Law Department Performance topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit, Insurance and Healthcare industries

Since the year 1980, we have all comfortably understood the line between maximizing your interest recovery and becoming a loan shark. The criminal interest rate was set at a simple 60% per annum. The Criminal Code made it an offence to: (a) enter into a new agreement that calls for an illegal interest rate; or (b) to collect an illegal interest rate. Complicating matters, proof of the illegal interest rate required the opinion of a duly licensed actuary.

But the times, they are a changin'. On January 1, 2025, a new criminal interest regime came into force. The new criminal interest rate is set at 35% ... sort of, but not always.

Whereas once there was one rate to rule them all, the new regime creates various and differing rate prohibitions. The objective of this brief paper is to outline the new regime, highlight the differences as compared to the old regime, and provide some tips to avoid becoming an accidental loan shark.

The old versus the new

The pre-2025 provisions are as follows:

Criminal interest rate

347 (1) Despite any other Act of Parliament, everyone who enters into an agreement or arrangement to receive interest at a criminal rate, or receives a payment or partial payment of interest at a criminal rate, is

(a) guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding five years; or

(b) guilty of an offence punishable on summary conviction and liable to a fine of not more than $25,000 or to imprisonment for a term of not more than two years less a day, or to both.

(2) In this section,

...

criminal rate means an effective annual rate of interest calculated in accordance with generally accepted actuarial practices and principles that exceeds sixty per cent on the credit advanced under an agreement or arrangement; (taux criminel)1

The new provisions were first set out in the Budget Implementation Act, 2023, No. 12 at sections 610 to 612:

Amendments to the Act

610 (1) The definition criminal rate in subsection 347(2) of the Criminal Code is replaced by the following:

criminal rate means an annual percentage rate of interest calculated in accordance with generally accepted actuarial practices and principles that exceeds 35 per cent on the credit advanced; (taux criminel)

There are some additional changes, including exceptions to the 35% rate, that will be examined below.

The calculation of interest

One of the more immediate differences worthy of note is that the method of measuring interest has been changed. In the previous legislation, the prohibited rate is measured as an effective annual rate (EAR). By contrast, in the new legislation, the prohibited rate is measured as an annual percentage rate (APR).

So, what is the difference? Simply put, it is a question of compounding interest. EAR takes into account compounding interest, whereas APR does not.

Assume a $100,000 loan at 48% interest, compounding monthly, with no payments required for one year. The total interest payable at the end of the year is $60,103.223. Thus a 60% EAR prohibition bans loans at a rate of approximately 48% per annum (compounded monthly without payments).

By contrast, APR is a straight annual percentage calculation without regard to compounding.

So, the reduction from 60% EAR to 35% APR is, in reality, a reduction from 48% APR to 35% APR.

The exceptions to the 35% regime

However, the 35% rate is not universal. Parliament has issued certain regulations, which came into force on the same day as the new Criminal Code provisions. The Criminal Interest Rate Regulations4 (Regulations) create a different regime for business loans.5

The Regulations state:

1 For the purposes of subsection 347.01(1) of the Criminal Code, section 347 of that Act does not apply in respect of an agreement or arrangement if

(a) the borrower is not a natural person;

(b) the borrowing is for a business or commercial purpose; and

(c) either

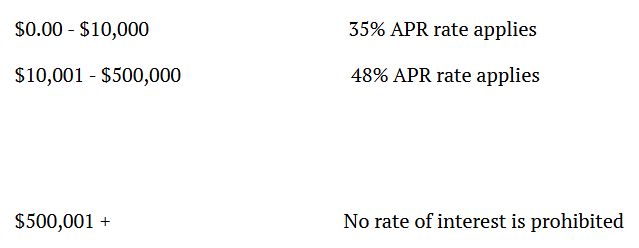

(i) the amount of the credit advanced is more than $10,000 but less than or equal to $500,000 and the annual percentage rate of interest — calculated in accordance with generally accepted actuarial practices and principles — does not exceed 48% on the credit advanced, or

(ii) the amount of the credit advanced is more than $500,000.

Let's unpack those provisions. Firstly, the elements are conjunctive. That is to say, to avail one's self of the exceptions, ALL of (a)(b) and (c) must be present.

Subsection (a) makes clear that the exception only applies where the borrower is not a natural person. Presumably this includes any legal entity other than a human being, such as a corporation or a limited partnership. It is less clear how this would apply in respect of a trust.

Subsection (b) limits the exclusion to where the borrowing is for a "business or commercial purpose." There is precious little information available as to what would constitute a business or commercial purpose. At the margins, these assessments become more difficult, particularly as the borrower's objectives may change over the life of the loan. There is a significant realm of uncertainty on this element of the test.

Subsection (c) creates the carve-out regime, and provides for three different rate prohibitions based on the size of the loan:

Allow me to reiterate: loans of more than $500,000 to corporations for business purposes are no longer subject to any maximum rate. The sky's the limit. Charge a million percent interest if you want.

The explanatory notes to the Regulations explain that the removal of the prohibition entirely for loans above $500,000 is "to avoid contractual frictions and ensure healthy and productive investments in areas of venture capital and private equity ... Commercial lending transactions above $500,000 represent a level of sophistication that does not require protection through the criminal interest rate provisions."

I leave it to the reader to decide whether that is a compelling justification. In this author's eyes, it is a very flimsy justification. Transactions above $500,000 are not necessarily between equally sophisticated parties. Now there is no limit whatsoever to the heights a lender may scale to impose a truly onerous obligation on a non-natural person commercial borrower. A small business loan can easily involve more than $500,000, and those agreements are rarely the subject of equal bargaining power.

Pitfalls for the unwary

The most common way that lenders accidentally become loan sharks is by failing to account for fees and for term. Allow me to illustrate:

- Lender loans $100,000

- Stated interest rate is 12%

- Lender fee of $10,000

- Repayable in one month

One would be forgiven for believing that a 10% loan doesn't come anywhere close to the 60% EAR or even the 35% APR prohibition. However, counsel must take caution to understand the definition of "interest" in the Criminal Code:

interest means the aggregate of all charges and expenses, whether in the form of a fee, fine, penalty, commission or other similar charge or expense or in any other form, paid or payable for the advancing of credit under an agreement or arrangement ...6

In our example, the $10,000 lender fee must be included in the interest amount. When the loan is repaid on time at the one-month mark, the lender will recover $11,000 in interest as defined under the Criminal Code. And since the prohibited rate is expressed as an annual rate, it must be extrapolated forward. If the lender recovered $11,000 every month for 12 months, the annual return would total $132,000 in interest on a loan of $100,000, or 132% interest (without accounting for compounding). So, the short-term lender has accidentally become a loan shark.

Transition provisions

Parliament made the transition easy. The rule is simple: old loans are under the prior regime, new loans (post-January 1, 2025) are subject to the new regime. Old loans are compliant if they are less than 60% EAR, new loans must be at 35% APR ... or 48% APR ... or no limit at all.

Unknowns

The new regime leaves a great deal uncertain, most important of which is the impact on guarantors. If a loan is made: (a) to a non-natural person; (b) for a commercial purpose; and (c) is more than $500,000, there is no limit on the interest rate.

The entire objective of the new regime is to prevent individuals from being overwhelmed with high-interest debt. However, there is seemingly no provision prohibiting the collection of a high-interest loan from an individual guarantor of a corporate debtor.

Taking the small business loan example, it is not uncommon for those loans to require personal guarantees. If the business fails, the guarantor is liable for the debt, and the new regime seemingly permits unlimited interest rates. It is difficult to accept that this outcome was intended by Parliament, and it will be interesting to see how the courts grapple with this inevitability.

Footnotes

1. RSC 1985, c C-46 | Criminal Code | CanLII

2.Budget Implementation Act, 2023, No. 1

3. $160,103.22 = $100,000(1+0.48/12)12x1

4. Criminal Interest Rate Regulations, SOR/2024-114, (https://canlii.ca/t/56g1r)

5. There are also carve-outs for payday loans, but they have nothing to do with real estate, so those provisions will not be addressed in this paper.

6. Criminal Code, s.347(2) https://canlii.ca/t/7vf2#sec347

Originally published by Lexpert Legal Insight on November 11, 2025

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.