- within Tax, Energy and Natural Resources and International Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Media & Information industries

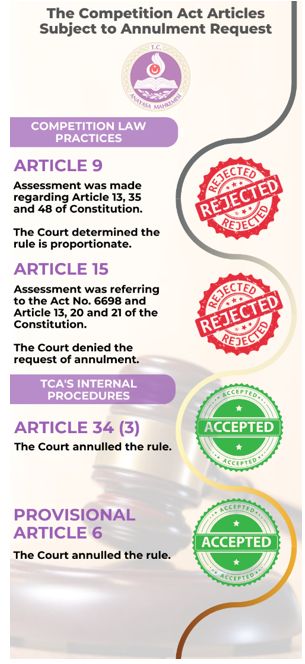

In June 2020, Turkish Competition Act was revised. In this context, significant amendments were made relating to commitment, reconciliation, de minimis, power to conduct dawn raids, and the internal functioning of the Turkish Competition Authority ("TCA"). Subsequently, 134 members of the parliament filed a legal challenge with the Constitutional Court ("Court"), seeking the annulment of four provisions, two of which were related to competition infringement detection and sanction procedure (Articles 9 and 15) and two concerning the internal administrative procedures of the TCA. Thereupon, on November 9th, 2022, the Court ("Court") rejected the plea to annul the amendments made to Articles 9 and 15 of the Act, which dealt with competition law practices and annulment of two amendments that pertained to the internal administrative procedures of the TCA.

This article will focus on the Court's assessment of Article 9, "Termination of Infringement," and Article 15, which governs the TCA's powers to conduct dawn raids.

Analysis of the Amendment regarding Article 9

Article 9 empowers the Turkish Competition Board ("Board") to take action to terminate the restriction of competition in cases where conduct and actions violate Articles 4, 6, or 7 of the Competition Act. These remedies are categorized as behavioral and structural. Behavioral remedies impose obligations on how undertakings compete in the market, utilize their assets, or enter into agreements with other undertakings. If behavioral remedies fail to produce the desired outcome, the Board may resort to structural remedies, which involve transferring specific activities, shares, or assets of undertakings.

The plea for annulment argued that this rule allowed for the transfer of assets without judicial due process, infringing on the freedom of property and undertakings and potentially causing severe and irreparable damages to the undertakings subject to measure. The Court evaluated Article 35 of the Constitution, which safeguards the right to property, Article 48, which ensures the freedom of labor and contract, and Article 13, which protects fundamental rights and freedoms. The Court concluded that the structural measures introduced in the rule were proportionate to the violation and necessary to eliminate it, causing no disproportionate interference or unreasonable restriction on the aforementioned rights.

Analysis of the Amendment regarding Article 15

The Court examined the request for the annulment of the phrase "may take copies and physical samples thereof" in the amended Article 15 of the Act. The annulment request was based on the argument that the rule in question allows the copying and sampling of all kinds of documents of the undertakings without any limitation and that the rule authorizing access to data involving trade secrets of the undertakings does not include any guarantee regarding the acquisition and processing of personal data.

In its assessment, the Court primarily considered Article 20 of the Constitution, which regulates the right to privacy. The Court states that the protection of personal data and the right to request such protection are guaranteed within the scope of protecting the right to privacy. Furthermore, the Court interprets that data relating to legal entities and natural persons should be considered within the scope of the article, based on the phrase "Everyone..." in the text of the relevant article.

The right to request personal data protection is restricted by the power to exercise dawn raids in Article 15 of the Act. The Court accepts that this restriction meets the condition of legality in accordance with the principle of "rights and freedoms can only be restricted by law" in Article 13 of the Constitution and has a legitimate constitutional purpose.

The Court emphasizes the necessity of obtaining copies and physical samples of all kinds of data and documents in the books, physical and electronic media, and information systems obtained during the examination to uncover competition violations. The Court concludes that the criterion of the limitation stipulated by the rule is necessary to achieve the aforementioned purpose has been met. It has been determined that the rule stipulates that copies and physical samples of books, documents, records and data, which are evidence for detecting competition violations, meet the necessary guarantees regarding the protection of personal data.

Another noteworthy point in the Court's assessment is that while reviewing the constitutionality of the rule requested to be annulled, the Court referred to the Personal Data Protection Act for the legal guarantees on the right to protection of personal data. The guarantees in question are to obtain information, the right to access data, the right to know whether the data is used for its intended purposes, and the right to ensure the security of the data. As stated by the Court, the proposed rule for annulment provides legal guarantees and does not unduly interfere with the operations of businesses and business associations. It also does not unreasonably restrict the right to request the safeguarding of personal data. However, as per Article 148 of the Constitution, the Court is authorized to directly assess the compatibility of laws with the Constitution. As the Court has conducted, analyzing the constitutionality of the law under review in provisions protected by other laws is not an appropriate approach and would result in a decrease in the effectiveness of the constitutional judiciary.

On the other hand, the decision was not unanimous, with five members out of fifteen, including the President and Deputy President of the Court, casting dissenting votes. The dissenting opinions emphasize two key points. Firstly, the right to inviolability of domicile is interpreted broadly to include workplaces in the European Court of Human Rights judgments. The Court and Article 21 of the Constitution stipulate that no one's residence may be entered or searched without a duly issued judge's warrant.

Secondly, the rule under review does not regulate how the information and documents, including personal data subject to inspection, will be used, where this information will be processed and stored, and what kind of inspection will be carried out to prevent abuse of authorization. Therefore, it is argued that the rule, which restricts the right to request the protection of personal data, is not specific and foreseeable in a way that does not allow arbitrariness and therefore does not meet the requirement of legality.

Conclusion

The Court's decision emphasizes the need for clear and specific regulations to prevent the abuse of TCA powers and protect individuals' rights. It is worth noting that Article 13, stipulating that fundamental rights and freedoms may be restricted by law, played a decisive role in the Court's decision. Therefore, any restrictions on individual rights and freedoms must be specified in the law and not introduced through secondary regulations or decisions by the Board. Otherwise, the restrictions would be against the Constitution. Ultimately, this decision serves as a reminder that a delicate balance must be maintained to protect both the competition and the fundamental rights. Also, the emphasis on Article 13 of the Constitution indicates that the debate surrounding the power to conduct dawn raids, as regulated under Article 15 of the Act, by way of secondary regulations or through the Board's decision, will likely endure for a considerable period.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.