On April 30, 2025, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued another reminder about the importance of adequate support in the specification for computer-implemented inventions. See, Fintiv, Inc. v. PayPal Holdings, Inc., No. 2023-2313.

The case involved four patents: U.S. Patent Nos. 9,892,386; 11,120,413; 9,208,488; and 10,438,196. During claim construction, the parties disputed the issue of whether certain claim elements were means plus function elements governed by 35 USC 112(f)1, and if so, whether the elements were adequately supported by the specification. The Court referred to these claim elements as the "payment handler terms".

Means plus function elements in computer-implemented inventions:

The Patent Act authorizes means plus function elements in 35 USC 112(f):

(f)Element in Claim for a Combination.—

An element in a claim for a combination may be expressed as a means or step for performing a specified function without the recital of structure, material, or acts in support thereof, and such claim shall be construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof.

In the relevant patents, none of the payment handler terms used the word "means." Thus, the Court noted the rebuttable presumption that § 112(f) does not apply.2 It is well established that this presumption can be overcome, and § 112(f) will apply, if a challenger demonstrates that the claim term fails to recite sufficiently definite structure or else recites function without reciting sufficient structure for performing that function.

The payment handler terms in the Fintiv patents appear as follows:

a payment handler service operable to use [application programming interfaces (APIs)] of different payment processors including one or more APIs of banks, credit and debit cards processors, bill payment processors.

a payment handler configured to use APIs of different payment processors including one or more APIs of banks, credit and debit cards processors, and bill payment processors.

a payment handler that exposes a common API for interacting with different payment processors.

Ruling from the bench during claim construction, Judge Albright of the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Texas found the payment handler terms to be means plus function terms, stating that the terms recited functions without reciting sufficient structure for performing the functions. The District Court concluded that the claim term "handler" was essentially a "nonce" word, i.e., a generic description of software or hardware that performs the functions. Finding no supporting structure in the specification, Judge Albright held the payment handler terms indefinite.

On appeal, Fintiv argued that the payment handler terms were not nonce terms, and that extrinsic evidence showed that the terms connoted structure. Fintiv analogized its claim terms to those in Dyfan, LLC v. Target Corp., 28 F.4th 1360 (Fed. Cir. 2022), in which the Court found terms like "code" and "application" to connote structure. Fintiv further argued that its use of the connecting term "configured to" is more often used with structural terms, rather than nonstructural terms.

The Court of Appeals rejected Fintiv's arguments. The Court found that the record generally supports the District Court's conclusion that the payment handler terms did not connote sufficient structure, and that the patent and claims differed substantially from Dyfan. The court further stated that the term "configured to" does not necessarily avoid a determination of means plus function. Accordingly, the Court affirmed the finding that the payment handler terms were properly construed as means plus function elements under 35 USC 112(f), and moreover, that the terms were indefinite.

Requisite support for computer-implemented means plus function elements:

Means plus function elements are construed to cover the corresponding structure, material, or acts described in the specification and equivalents thereof. Accordingly, to properly determine the scope of a means plus function element, the specification must disclose corresponding structure that is adequate to achieve the claimed function. Absent such disclosure, the claim element is considered indefinite.

In many computer-implemented inventions, the corresponding function may be performed by a general purpose computer or microprocessor. In such cases, courts have required that mere disclosure of generic computer hardware may not be sufficient; and the specification should disclose an algorithm that the generic hardware performs to accomplish the function.

Importantly, means plus function elements require disclosure in the specification even if the means are already well known in the art. As stated by the Federal Circuit:

The fact that an ordinarily skilled artisan might be able to design a program to create an access control list based on the system users' predetermined roles goes to enablement. The question before us is whether the specification contains a sufficiently precise description of the "corresponding structure" to satisfy section 112, paragraph 6, not whether a person of skill in the art could devise some means to carry out the recited function.

Blackboard v. Desire2Learn, slip op. pages 24-25 (Fed. Cir. 2009).

In other words, support in the specification for the means plus function element must satisfy the "written description" requirement, as well as the "enablement" requirement. To satisfy the written description requirement one cannot rely solely on the knowledge of those of ordinary skill in the art (as can be done when satisfying the enablement requirement). For example, if one skilled in the art might know of more than one way to perform the recited function, the specification must identify the way (or ways) contemplated by the inventor. For at least that reason, it may be helpful to disclose multiple embodiments in the specification.

For Computer-Implemented Inventions, the Corresponding Structure is an Algorithm:

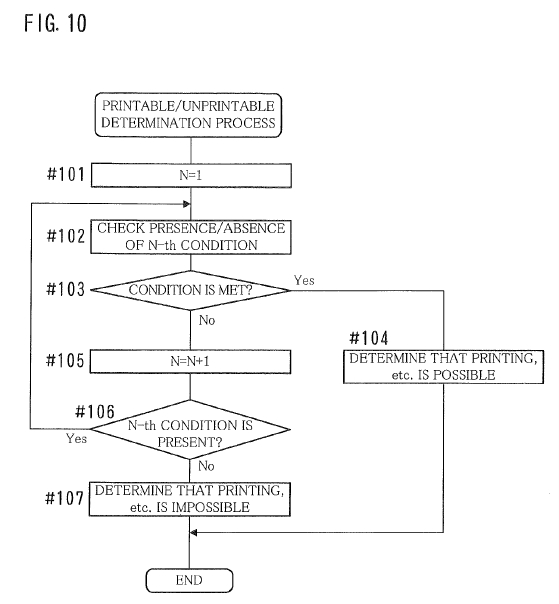

As stated in MPEP § 2181(II)(B), an algorithm is defined broadly, for example, as "a finite sequence of steps for solving a logical or mathematical problem or performing a task." Microsoft Computer Dictionary, Microsoft Press, 5th edition, 2002. An Applicant may express the algorithm in any understandable terms: as a mathematical formula, in prose, in a flow chart, or "in any other manner that provides sufficient structure."

In practice, it is important to be sure that the specification describes each computer-implemented function with as much (step-by-step) detail as possible. Include, if possible, a flowchart in the drawings with a corresponding description in the specification.

Written Description Requirement:

For computer-implemented inventions, the written description requirement of 35 USC § 112(a) is more important than enablement. Specifically, in fulfilling the enablement requirement the specification can omit description of features that are well known to those of ordinary skill in the art. However, such is not the case with regard to the written description requirement.

As required by the statute, "...the patentee must disclose sufficient information to demonstrate that the inventor had possession of the invention at the time of filing...".

The MPEP states that:

To satisfy the written description requirement, a patent specification must describe the claimed invention in sufficient detail that one skilled in the art can reasonably conclude that the inventor had possession of the claimed invention....Possession may be shown in a variety of ways including description of an actual reduction to practice, or by showing that the invention was "ready for patenting" such as by the disclosure of drawings or structural chemical formulas that show that the invention was complete, or by describing distinguishing identifying characteristics sufficient to show that the applicant was in possession of the claimed invention.

This requirement is generally interpreted to mean that, for computer-implemented inventions, the inventor must disclose more than the functions intended to be performed or the results thereof. Without detailed supporting structure, i.e., algorithms, the claim is alleged to pre-empt the entire function, when the inventor is only entitled to claim the means by which the inventor envisioned performing the function.

Practice Tips:

It is generally improper to read elements from the specification into the claim to narrow the scope of the claim. Accordingly, providing a detailed specification will not necessarily result in a narrow claim scope. However, under current USPTO practice, failing to provide a description of at least one specific application of a computer-implemented invention in the specification, could result in the claim being held invalid or unpatentable when the claim terms are construed as means plus function terms. In particular, it is best if the description of the at least one specific application of the computer-implemented invention includes detail narrower in scope than the functional language of the claim. This should prevent the Examiner from alleging that the claim is an abstract idea and the inventor is attempting to preempt all applications of the abstract idea.

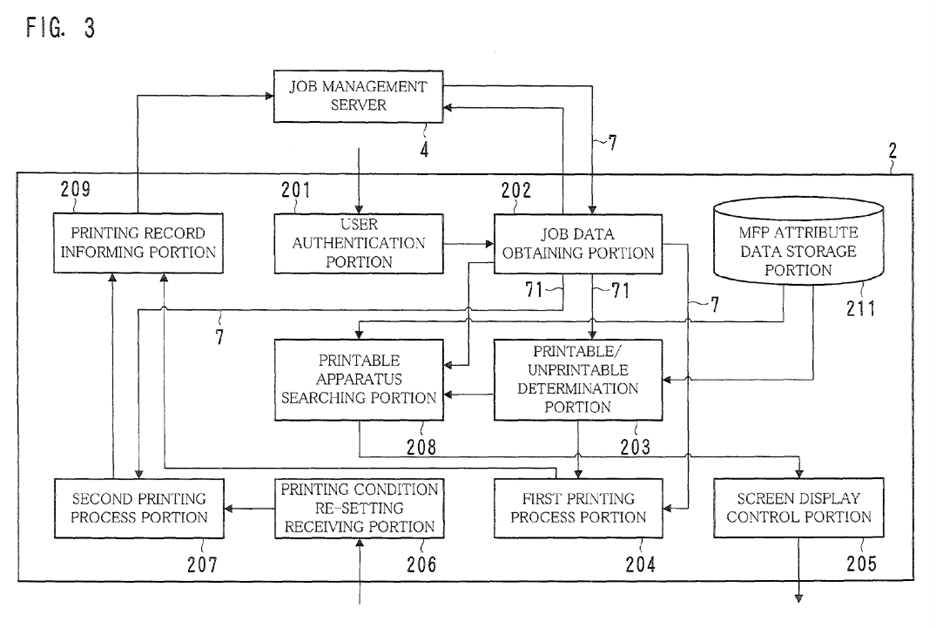

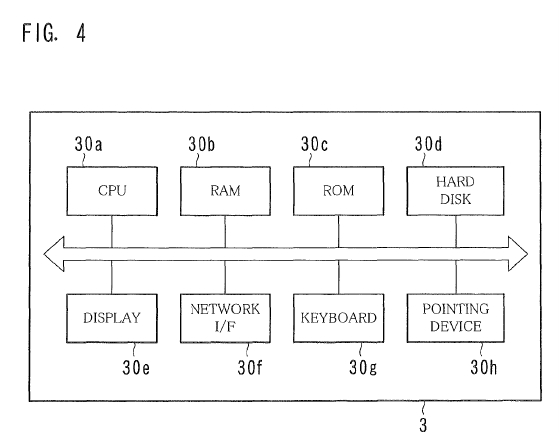

Another helpful strategy is to provide diagrams showing both the functional, as well as structural, aspects of an invention. For example, U.S. Patent No. 9,710,200 B2 includes both Figure 3, which is described as a functional configuration, as well as Figure 4, which is described as a hardware configuration:

And, of course, flowcharts are also excellent ways of disclosing a computer-implemented algorithm. See Figure 10, also from U.S. Patent No. 9,710,200 B2.

For applications being drafted outside the U.S., it is recommended to have U.S. counsel review applications prior to filing, or at least during the priority year. This can result in seemingly minor changes that can have significant impact given the unique U.S. requirements. This is particular relevant for computer-implemented applications, where the generic terminology common to international applications (e.g. in Europe) is commonly found to invoke a means plus function interpretation under U.S. law.

Footnotes

1 Due to the different dates of the patents, technically some of the patents are governed by 35 USC 112, paragraph six, and others by 35 USC 112(f). For simplicity, this article uses 35 USC 112(f).

2 Williamson v. Citrix Online, LLC, 792 F.3d 1339 (Fed. Cir. 2015)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.