Twenty years ago, on a warm summer day, Hawaii enacted a restriction on employer inquiries into an applicant's work history until after a conditional offer of employment. Intended to give applicants with criminal histories a fair shot at employment, the law—the first state "ban the box" law—crystalized a movement that, in time, would yield similar restrictions in 12 states and 17 localities (for private employers). The result is a crisscrossing jumble of requirements with little uniformity, putting employers in a difficult position when dealing with applicants (and sometimes even existing employees) in different jurisdictions.

As the ban the box movement comes of age, it finds itself at a crossroads, with some jurisdictions passing new, aggressive restrictions and other jurisdictions seeking to limit local ban the box laws altogether. Indeed, the term "ban the box" itself, once a clear reference to a specific criminal history box on an employment application, has taken on a broader meaning, with some ban the box laws now including restrictions on employer consideration and use of certain criminal information, unique pre-adverse and adverse action letter requirements, and other requirements well beyond the "box." Twenty years after the first ban the box law, the movement thrives, but with a disjointed and sometimes inconsistent framework.

A brief note on scope: This article analyzes state and locality ban the box requirements for private employers; there is no federal ban the box statute for private employers. There are additional requirements applicable to certain public employers and their contractors.

Going Beyond the Box

Although the earliest ban-the-box laws limited initial criminal history inquiries by literally banning a box on an employment application asking whether an applicant had ever been convicted of a crime, many of the more recent laws go well beyond this basic restriction. Today's ban the box laws may impact several areas, including (1) the timing of certain criminal history inquiries, authorizations, and/or background checks; (2) employer consideration and use of criminal history information; and (3) unique pre-adverse and adverse action requirements (beyond those required by the federal Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA) and Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964).

Timing Restrictions

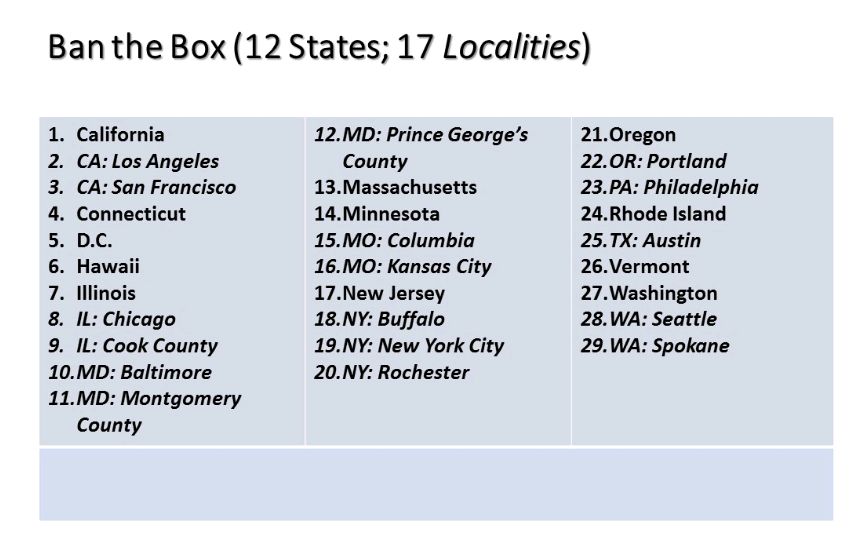

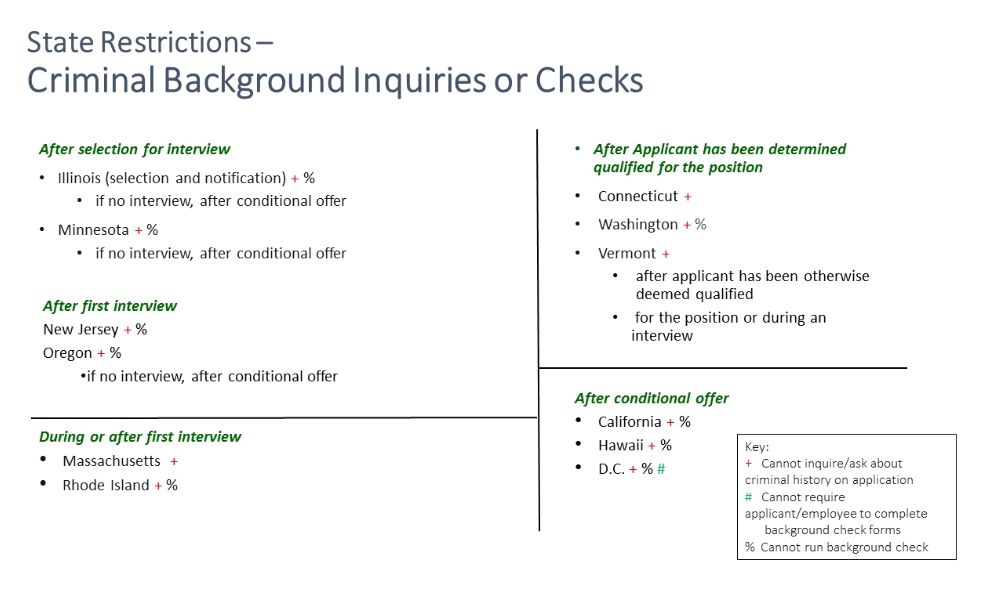

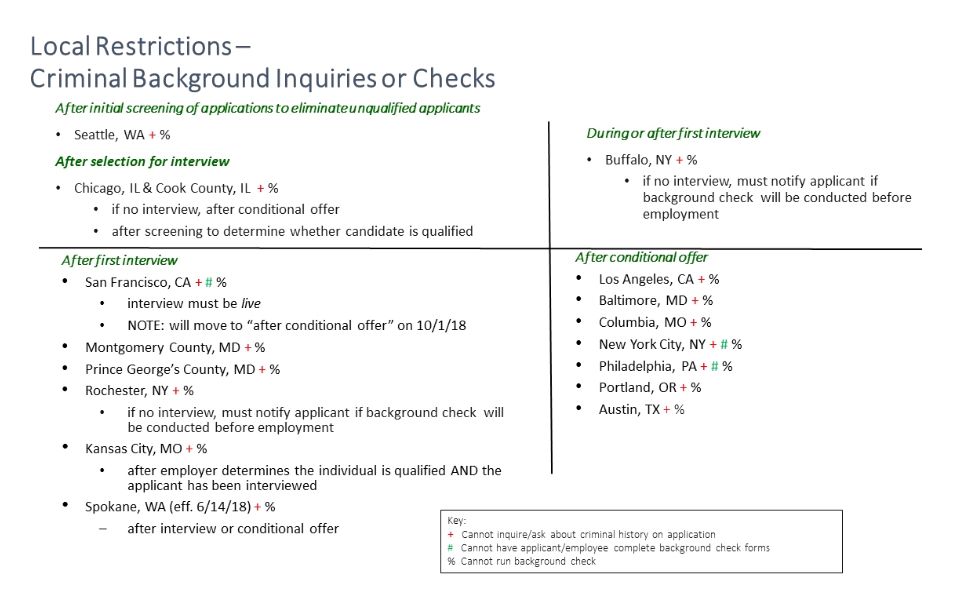

Depending on the jurisdiction, ban the box state and local laws regulate the timing of three main employer actions during the employment application process: (a) inquiring about criminal history; (b) providing disclosures and requiring completion of a background check authorization form; and/or (c) actually conducting a background check. Although few jurisdictions have adopted exactly the same standard, these timing restrictions generally take one of four approaches as to when these activities can occur: (1) after a candidate is found qualified; (2) after a candidate is selected for an interview; (3) during or after an interview; and (4) after a conditional employment offer. Please see Figure 1 for a list of jurisdictions with ban the box restrictions for private employers, Figure 2 for state timing restrictions, and Figure 3 for local timing restrictions.

Figure 1

Figure 2

Figure 3

For employers that want one approach across all states and localities, the lowest common denominator/most conservative approach is to wait until after a conditional offer of employment has been made to ask about criminal convictions, require review of the background check disclosures/completion of the background check authorization, and run a background check. However, only 10 of the 29 ban the box jurisdictions (roughly 35 percent) are that restrictive. The other 65 percent of the states and localities with ban the box restrictions typically allow inquiries and background checks earlier—after a first interview, for example. Thus, if a private employer adopts an "after conditional offer" approach (often for administrative ease), it will choose a more conservative approach than is required in 65 percent of locations with ban the box timing restrictions on inquiries, solicitation of forms, and/or actual background checks.

Of course, the overwhelming majority of the states and localities in the United States have absolutely no ban the box restrictions on the timing of criminal history inquiries, authorizations, or background checks. In jurisdictions with no ban the box timing restrictions, or ones with trigger points earlier in the application process, many employers pose the prior criminal history question to applicants before a conditional offer for two reasons: (1) as an initial test of applicant truthfulness and veracity, and (2) as a safeguard against possible background check inaccuracies (which occur more regularly than employers would like given missing/incorrect information and look-back limitations). Employers must decide whether they prefer the administrative convenience of the lowest common denominator approach or the advantages (e.g., applicant truthfulness, etc.) of complying with applicable laws on a state-by-state basis.

Restrictions on Employer Consideration and Use of Criminal History Information

Some ban the box laws also impose restrictions on a private employer's consideration and use of criminal history information, beyond the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission's (EEOC) Title VII guidance (i.e., beyond considering the three "green" factors: (1) the nature and gravity of the offense or conduct; (2) the time that has passed since the offense or conduct; and (3) the nature of job held or sought). For instance, New York City's ban the box law requires the consideration of eight specific factors when evaluating criminal history information in an employment context. Other jurisdictions prohibit altogether the consideration of certain criminal records. For example, San Francisco's ban the box law bans the consideration of certain convictions for crimes that have been decriminalized since the original conviction.

Jurisdictions with ban the box laws on the consideration and use of arrest and conviction history information beyond the EEOC's three factors include (in order by state and then, within each respective state, by locality): California (statewide; Los Angeles and San Francisco); Washington, D.C. (district-wide); Hawaii (statewide); Maryland (Prince George's County); Missouri (Columbia and Kansas City); New York (Buffalo, New York City, and Rochester); Pennsylvania (Philadelphia); and Washington (Seattle). Some of these have much more extensive and restrictive provisions than Title VII.

Notification of Possible (and Then Actual) Adverse Action

Expanded Pre-Adverse Action Notification Requirements

Although pre-adverse action notification is required by the FCRA, a growing number of ban the box laws require state- and locality-specific pre-adverse action notification/letters with unique jurisdiction-specific language. These requirements vary widely, including language that (1) identifies the specific criminal offense potentially triggering the proposed adverse action; (2) requests additional information from an individual; and/or (3) provides a jurisdiction-specific analysis of an individual's criminal history information. Jurisdictions with enhanced pre-adverse action letter requirements include (in order by state and then, within each respective state, by locality): California (statewide; Los Angeles); Maryland (Montgomery County and Prince George's County); New York (New York City); Pennsylvania (Philadelphia); and Washington (Seattle).

Two jurisdictions—New York City and Los Angeles—have ban the box laws that greatly expand the FCRA pre-adverse action process by requiring additional steps and mandating the use of specific forms throughout the pre-adverse/adverse action process. Fortunately, the New York City and Los Angeles ban the box laws apply only to individuals applying to work within those jurisdictions.

Expanded Waiting Period

The FCRA requires an employer to wait a reasonable period of time before taking adverse action in order to allow the applicant/employee to dispute the report. While five business days is usually the least amount of time that has been deemed to be a reasonable waiting period, a number of ban the box jurisdictions — including San Francisco, California; Montgomery County, Maryland; Prince George's County, Maryland; New York City, New York; and Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—have longer periods (some of which can be as long as 10 days).

Expanded Adverse Action Notification Requirements

While most ban the box laws have not included adverse action letter requirements beyond those mandated by the FCRA, a few jurisdictions have mandated additional adverse action letter language. For instance, Portland, Oregon, requires that an employer identify the specific crime leading to the adverse action in an adverse action letter; Los Angeles requires that an employer provide a revised analysis of the job-relatedness of a specific crime at the time of the adverse action letter in certain circumstances; and California (statewide) now requires notice in the adverse action letter of certain rights an individual may have.

Stopping the Party?

Given the huge impact that the variety and differences in approach among the different state and local ban the box laws have had on employers—particularly those that operate in multiple jurisdictions or recruit nationwide—some policymakers have begun to question the cost of different ban the box initiatives on employers. To this end, New Jersey, Indiana, and Michigan have instituted laws that limit local ban the box laws. Thus, as the ban the box movement seems to be accelerating among certain jurisdictions (particularly in the western United States), other jurisdictions seem to be pumping the brakes. While this "banning the ban" movement is in its infancy, it remains to be seen how it will impact other states and regions.

Employer Takeaways

Private employers should decide what is more important: a one-size-fits-all approach or an earlier test of applicant truthfulness and access to full and complete information in addition to the background check report (since background check reports are not always accurate).

- If a one-size-fits-all approach makes sense, consider waiting until after a conditional offer to ask applicants questions about criminal history, present applicants with background check disclosures or secure applicant authorization, or to conduct background checks.

- If an earlier test is appropriate, review and comply with applicable ban the box requirements and restrictions (if any).

Private employers also should consider the compliance requirements of expanded employer consideration and use restrictions and pre-adverse and adverse action notification requirements.

Further information on state and local ban-the-box laws, including all federal and state background check requirements, are summarized in the firm's O-D Comply: Background Checks and O-D Comply: Employment Applications subscription materials, which are updated and provided to O-D Comply subscribers as the law changes.

For an in-depth look at ban the box restrictions across the country, join us for our upcoming webinar, "'Ban the Box' Turns 20: What Employers Need to Know about the Current Framework," featuring attorneys from Ogletree Deakins' Background Checks Practice Group on September 18, 2018, at 2:00 p.m. Eastern. To register for this timely program, click here.

A version of this article was previously published in Law360.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.