- with readers working within the Advertising & Public Relations, Aerospace & Defence and Technology industries

No matter how much advance warning is provided or experience garnered, employers and employees are often caught off guard by the devastation and uncertainty natural disasters create. Whether wildfires, hurricanes, tornadoes, earthquakes, flooding, or even global pandemics, disasters have the capacity to disrupt ordinary life for the short and long term. Employers often need to address several employment-related concerns when such emergencies arise. While not all-encompassing, this Littler Report highlights some common workplace issues natural disasters generate.

WAGE AND HOUR IMPLICATIONS

There are several payroll-related concerns that can be triggered by a disaster or inclement weather event. We begin with a refresher on who must get paid when operations are shuttered. Employers should be aware that additional laws—particularly at the state and local levels—may be in play.

- Non-Exempt Employees. Under the FLSA,

non-exempt workers must be paid only for the time they work. As a

result, employers need not compensate non-exempt employees who are

not working because of an emergency. It does not matter whether the

absence is based on the employer's decision to close or the

employee's decision to stay home or evacuate.

There may be exceptions during a weather or other natural event for waiting time, or on-call time. The FLSA considers employees to be "on call" if they must remain on the employer's premises and are unable to use their time for their own purposes. State laws may address this question as well. Florida, Georgia, and Mississippi, for example, do not have any additional on-call provisions. Other states— such as California, Massachusetts, Minnesota and New Jersey—have guidance on this topic that may be relevant.

Employers should remember that they must pay non-exempt employees for performing any work remotely, even if the employee did not have express permission to work from home. To help minimize risk, and to the extent they have not already done so, employers should implement and enforce a clear time and attendance policy that, among other things, requires non-exempt employees to accurately record all time worked. Employers in some states, including California, will also be liable for any expenses reasonably incurred in working remotely by both exempt and non-exempt employees.

- Exempt Employees. When an employer shuts down

its operations because of adverse weather or other calamity for

less than a full workweek, exempt employees must be paid their full

salary. This rule also applies if exempt employees work only part

of a day. If an employer deducts from the employee's salary in

such situations, it risks losing the exemption applicable to that

employee.

Barring any state law or overly restrictive company policy to the contrary, exempt employees may be required to use accrued leave or vacation time (in full or partial days) for their absences, including if the worksite is closed. While it might not be a popular move, an employer can direct exempt employees to take paid time off for the closure, pursuant to the employer's bona fide leave or vacation policy. If an employee does not earn or does not have any available leave time, the employee is entitled to their full guaranteed salary if the employer decides to close.

On the other hand, if an employer is open for business, an exempt employee who elects to stay home due to the disaster situation is considered absent for personal reasons. In lieu of paying salary, an employer with a bona fide leave or vacation policy may require the employee to use their accrued paid time off to cover the absence. If permitted by state law, leave time in this circumstance may be taken in full or partial days.

- Potential Payroll Delays. One possible

consequence of a natural or other disaster is the delayed

processing of employees' wage payments. This situation can

cause employers to unintentionally run afoul of many state laws

that govern: (a) the frequency of wage payments; and/or (b) notice

to employees of changes in paydays or wage rates, etc. For example,

Louisiana law requires payment of wages no less than twice a month

for employees who are non-exempt under the FLSA in certain

occupations, such as manufacturing and oil and mining operations.

Louisiana law further mandates that employers notify employees of

any changes in the method and frequency in which they will be paid.

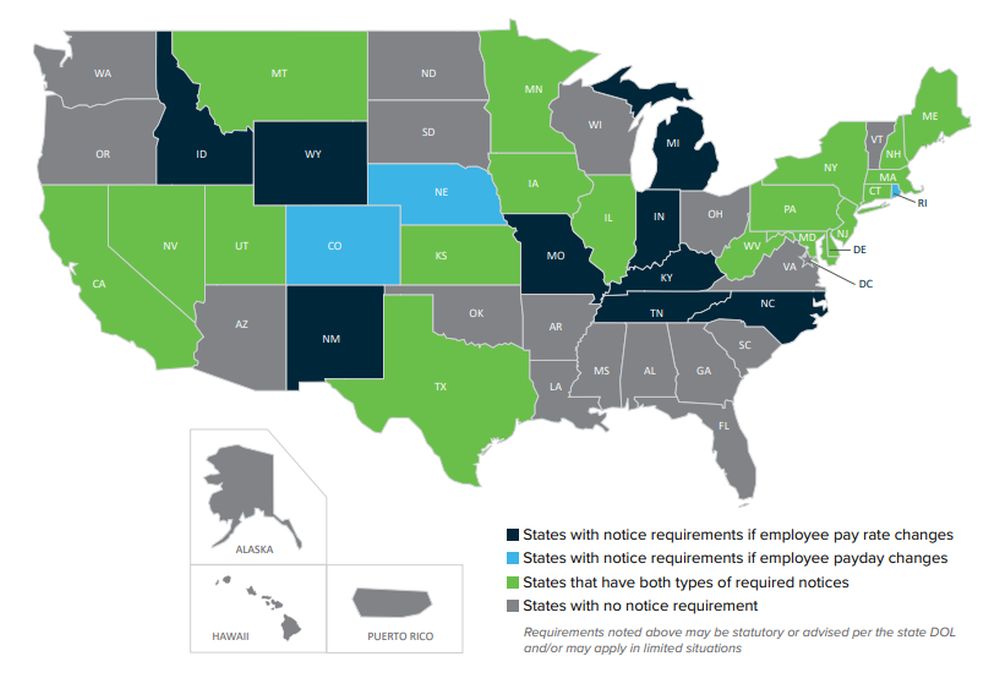

Numerous states—including Alaska, California, Colorado,

Hawaii, Illinois, Maryland, Nevada and New York, among

others—also require notice to employees for changes in their

pay rate and/or payday.

Even in states (like Florida) that do not have specific laws on point, local payroll processing delays may affect employees in other jurisdictions as well. Employers should be mindful of requirements wherever employees are located and respond accordingly. For example, if the timely payment of wages to employees in California is compromised by a flood elsewhere, an employer may be subject to monetary penalties under California's labor code. Notice of any delays should be made in writing, as soon as practicable, and is warranted particularly where employees are on direct deposit and might otherwise write checks against anticipated deposits. Open and ongoing communication with employees about wages, scheduling, and related matters is recommended throughout the recovery. A sample Notice of Payroll Delay is included at the end of this Littler Report, within the Practical Materials section.

- Paycheck Advances. Given the significant toll

of a natural disaster, employers with sufficient ability might

consider paying wages (full or partial) for a set duration, even

where not required. This extra step could help plug the gap until

any government assistance may kick in. It can also obviously boost

morale, demonstrate loyalty, and enhance the employer's

reputation.

Employers should take steps to properly document any pay advancements to avoid any future questions of deductions in future wages that may result from any advancements. The voluntary payment of wages should be reported and treated as wages for tax purposes.

NATURAL DISASTERS

Notice for Changes to Payday or Pay Rate

LEAVES OF ABSENCE & RELATED ISSUES

Employees may need to take leave from work to deal with the ramifications of the natural disaster. While this section summarizes the more common types of leave and related topics, please be aware that additional laws—particularly at the state and local levels—may come into play.

- Family and Medical Leave. Employees who have suffered a serious injury or illness resulting from the disaster—or who have a family member who did—may be entitled to leave under the federal Family and Medical Leave Act (FMLA). State or local family and medical leave laws may also apply to certain employees. Even if not covered by federal, state, or local laws providing for time off for illness, an employee may qualify for sick or other leave under a company policy or collective bargaining agreement. As such, it is important to remind front-line managers and supervisors of governing policies on this subject and their possible application during this time period.

- State and Local Leave Laws. Many states and

localities have their own paid and unpaid leave requirements. Some

jurisdictions have extended existing leave entitlements to

emergency situations. For example, San Francisco has in place a

public health emergency leave ordinance that provides for leave in

the event of a "public health emergency," which includes

an "air quality emergency." Similarly, Oregon allows

employees to use leave under the state's paid sick and safe

leave law when they are under an evacuation order or when the air

quality index reaches a level that poses a risk to their health.

Even if an employer's worksite is not directly affected by a

natural disaster, employees still may be able to take protected

leave for related events. For example, Colorado allows employees to

take paid leave if their child's school or place of care is

closed due to a natural disaster, or where their place of residence

must be evacuated due to loss of power, heating, water, or other

unexpected events. Moreover, state and local leave laws may

prohibit employers from requiring employees to take unpaid leave in

circumstances that qualify for use of their accrued paid leave. It

is therefore important to review the local leave laws in all

jurisdictions in which the company operates, as well as state

declarations of emergency following a natural disaster.

Volunteer Emergency Responder Leave. Over 30 states protect employees who serve as volunteer emergency responders and are called into action during natural disasters. These laws often cover volunteer firefighters, emergency medical personnel, or volunteer rescue workers, though some are limited in the specific volunteer responder services that they address. When faced with employee requests to take time off to assist with relief and rescue efforts, employers should take care to confirm whether the requested relief is related to volunteer first responder duties so that they can appropriately determine employees' leave and reinstatement rights. In some states, employers may require documentation from the relevant department, certifying the need for the employee's assistance. These laws also prohibit retaliation against an employee because of their absence due to serving as a qualifying emergency responder.

- Uniformed Services Leave. Employees absent from work to assist with relief efforts may separately qualify for protected time off under the Uniformed Services Employment and Reemployment Rights Act of 1994 (USERRA). Under USERRA—which applies to every public and private employer and has no minimum employee requirement—employees may take a leave of absence for service in the uniformed services. For purposes of disaster relief, "uniformed services" include specified service by members of the National Disaster Medical System, appointment of a member of the National Urban Search and Rescue Response System, members of the National Guard if called by the president of the United States, and any other category of persons designated by the president during a time of national emergency. USERRA protections have also been extended to Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) reservists who deploy to major disaster and emergency sites, even if they do not provide notice of their absence from work due to deployment. Relatedly, uniformed services leave may be a requirement under state law, even in locations unaffected by a natural disaster. For example, New York requires employers to reemploy any employee who is a member of the national guard and leaves their job because they are activated by the governor of any other state.

- Leave-Sharing Programs. A popular, and

altruistic, employee benefit that some employers provide in a time

of crisis is a leave-sharing program. An employer-sponsored

leave-sharing program allows an employee to donate accrued hours of

paid vacation, or personal and potentially sick leave for the

benefit of other employees who are in need of taking more leave

than they have available. As with any employer-provided benefit,

there are specific requirements and tax consequences associated

with a leave-sharing program.

What leave can be donated may vary from state to state. For example, different states have different rules regarding an employee's right to different kinds of leave—whether accrued, earned or unearned, or whether vacation pay, sick pay or generic "paid time off." Thus, what may be donated to a leave-sharing plan may also vary from state to state. To the extent an employer provides only sick leave to benefit employees who are sick and does not provide for cashing out of sick leave upon termination, an employer will probably want to limit donations from available sick time to avoid claims that "unvested" sick leave is effectively vested.

Generally, the employee seeking to draw from the leave bank must provide the employer with a written application describing the need for such leave. Once the employer approves the application, the employee is eligible to receive additional leave, usually paid at their normal compensation rate, once their own accrued leave has been exhausted. In an IRS-eligible leave- sharing plan, special tax treatment applies to leave donors, recipients, and the employer.

- Leave-Based Donation Programs. In addition to the leave-sharing programs summarized above, the IRS may designate special treatment of leave-based donation programs in the event of a "qualified disaster." Under leave-based donation programs, employees forgo leave time to which they are otherwise entitled and authorize their employers to make donations, in the amount of the cash value of the time donated, to assist the victims of a qualified disaster. Donations must be directed to charitable organizations as described in section 170I of the Internal Revenue Code for this purpose. When the IRS announces this special status, it explains that leave-based donations will not constitute gross income or wages if made to appropriate charities and by a specified date. Employees, however, may not claim a charitable deduction.

- Voluntary Employer Leave. Even if applicable leave laws and employer policies and practices do not provide for non-medical leaves of absence, the circumstances of a natural disaster will probably present extraordinary circumstances that may allow an employer to grant the time off to employees directly or indirectly affected by the disaster. While strict adherence to leave policies is the conservative and prudent management approach for employers in normal operating circumstances, when a disaster strikes employers should be flexible and considerate by expanding or at least temporarily relaxing otherwise restrictive existing leave policies. In making exceptions, employers must remain mindful of local, state, and federal antidiscrimination laws, and ensure that such exceptions are based on legitimate, non-discriminatory reasons and are applied consistently across the workforce. Inconsistent application of workplace rules and policies are often relied upon by employees raising claims of discrimination. For a sample Natural Disaster Leave Request Form, please refer to the Practical Materials section of this Littler Report.

- Reasonable Accommodations. Employers must be mindful that civil rights laws will not be suspended during or after a natural disaster. In particular, employers should be prepared to handle employee requests for accommodation following a natural disaster, which might include a request for leave or to work remotely. The Americans with Disabilities Act (applicable to employers with 15 or more employees) and related state and local antidiscrimination laws require employers to provide reasonable accommodations to qualified employees with disabilities. Because employees who are physically or emotionally (e.g., post-traumatic stress disorder) injured by the impact of the natural disaster may be entitled to reasonable accommodation, employers should take all such inquiries seriously. Moreover, depending on the nature of the disaster, employees with mobility issues might not be able to travel to the work site. Allowing such employees to work remotely might be a viable option. Within the Practical Materials section we have included a brief Remote Work Program Checklist that flags important considerations for employers in instituting a temporary remote work program.

An employer-sponsored leave-sharing program for major disasters must comport with the following requirements:

- The plan must allow a leave donor to deposit unused accrued leave in an employer-sponsored leave bank for the benefit of other employees who have been adversely affected by a major disaster. An employee is considered adversely affected if the disaster has caused severe hardship to the employee or family member that requires the employee to be absent from work.

- The plan does not allow a donor to specify a particular recipient of their donated leave.

- The amount of leave donated in a year may not exceed the maximum amount of leave that an employee normally accrues during that year.

- A leave recipient may receive paid leave from the leave bank at the recipient's normal compensation rate.

- The plan must provide a reasonable limit on the period of time after the disaster has occurred, during which leave may be donated and received from the leave bank, based on the severity of the disaster.

- A recipient may not receive cash in lieu of using the paid leave received.

- The employer must make a reasonable determination of the amount of leave a recipient may receive.

- Leave deposited on account of a particular disaster may be used by only those employees affected by that disaster. In addition, any donated leave that has not been used by recipients by the end of the specified time must be returned to the donor within a reasonable time so that the donor may use the leave, except in the event the amount is so small as to make accounting for it unreasonable or impractical. The amount of leave returned must be in the same proportion as the leave donated.

A sample Disaster Leave Sharing Policy is included within the Practical Materials section.

Disaster response can involve numerous benefits and tax-related issues. Programs intended to benefit employees affected by the storm can be implemented by employers and/or may require employers to undertake administrative duties. While this Littler Report briefly addresses certain programs regulated by federal law, state laws may affect these options as well.

- Qualified Disaster Payments. Internal Revenue Code § 139 permits an employer to make a payment to an employee that constitutes "a qualified disaster relief payment," without any income or payroll tax withholding or consequences. Such payments include any amount paid to or for the benefit of an individual to reimburse or pay reasonable and necessary personal, family, living, or funeral expenses incurred as a result of a "qualified disaster," or to reimburse or pay reasonable and necessary expenses incurred for the repair or rehabilitation of a personal residence or its contents. A "qualified disaster" is generally declared by the president of the United States.

- Employer-Sponsored Public Charities. Under IRS rules, employers can create their own

public charities, which generally may "provide a broader range

of assistance to employees than can be provided by donor advised

funds or private foundations." Certain requirements must be

met to ensure that the charity does not impermissibly serve the

employer. Specifically:

- The class of beneficiaries (the "charitable class") must be a large and indefinite group;

- Recipients must be chosen "based on an objective determination of need;" and

- Recipients must be chosen "by an independent committee or

adequate substitute procedures must be in place to ensure that any

benefit to the employer is incidental and tenuous."

If those criteria are satisfied, the charity's payments to the employer-sponsor's workers and their families are treated as charitable and are not deemed compensation to the recipient-employee.

- Employer-Sponsored Private Foundations. Employer-sponsored private foundations also can assist employees and their families, but they may provide direct help only in the event of a "qualified disaster," as defined earlier. Such private foundations cannot make payments for "non-qualified disasters or in emergency hardship situations." Similar procedural requirements apply here as with employer-sponsored public charities, above.

- Loans or Hardship Distributions from Employer-Sponsored Retirement Plans. The IRS may elect to temporarily relax limitations on employee hardship distributions and loans from tax-qualified employer retirement plans (i.e., 401k and 403(b) plans) during natural catastrophes. For example, when this relief applies, the retirement plan can permit a victim to take a hardship distribution or to borrow up to the specified statutory limits from the individual's account, even if certain procedural plan requirements are not met. Relief would be limited to the areas affected by the specific event, as set forth in the pertinent IRS announcement. Following any natural disaster or similar event, employers should keep an eye out for this type of IRS announcement.

- Tax & Retirement Plan Duties. Employers are obliged to remit collected payroll taxes and complete reports to the state and federal governments. The IRS has the authority to ease these requirements as to federal obligations. The IRS commonly extends the deadlines for tax returns and tax payments following natural disasters. Latedeposit penalties for federal payroll and excise tax deposits also may be waived. Similarly, the IRS routinely announces extensions for deadlines associated with retirement plan obligations in the event of a major storm. For example, the IRS (with the Department of Labor and the Pension Benefit Guaranty Corporation) may elect to extend funding deadlines for affected single- and multi-employer plans and may also waive penalties for late contributions. States also frequently offer extra time for employers to file payroll reports or deposit taxes due to various, localized emergency situations. Again, employers should stay tuned for such announcements.

- Benefits Continuation. In a disaster, employers may be required to decide whether they will maintain benefits for employees— especially where the employee, or the business, may at least temporarily not be working or operating. Should an employer decide to continue coverage, it should contact its benefits vendors to determine how life, health, and disability coverage can be maintained. If a business closes indefinitely, a key issue to employees will be the status of the company's benefit plans and whether employees can continue to participate. COBRA (or other notice requirements) may be triggered if an employee loses eligibility or if the employer elects to terminate benefit plans.

Going forward, companies renewing insurance policies of all kinds should confirm the availability of benefits for natural disasters and or other catastrophic events, including what benefits or coverages are excluded.

To view the full article, click here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.