- within Tax topic(s)

The City of Philadelphia sued S.C. Johnson & Son, the manufacturer of Ziploc bags, and Bimbo Bakeries, the largest bakery company in the United States, alleging that the companies misled consumers by deceptively advertising that their single-use plastic bags are recyclable.

In announcing the lawsuit, Philly Mayor Cherelle L. Parker said, "Companies that label their products with the goal of implying their product is recyclable when it isn't are not just breaking the law, but they are violating public trust and contributing to waste."

Philly has a lot to say about plastic recycling in its more than forty-page complaint alleging violations of the City's own Consumer Protection Ordinance. But, at its core, here's what the case is about.

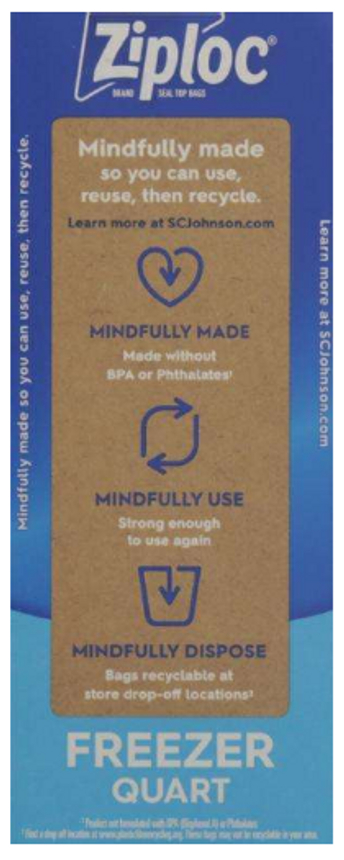

Plastic bags are not generally recyclable in curbside recycling programs. For the most part, the only practical way to recycle plastic bags is to set up special programs – such as store drop off programs – to collect the bags and bring them to facilities that are designed to process them. The City of Philadelphia alleged that S.C. Johnson and Bimbo Bakeries promoted their plastic bags as being recyclable, but misled consumers about what that really means.

Philly alleged that, although the companies generally advertised that their plastic bags are recyclable through store drop-off programs, consumers didn't really understand the "drop-off" part. The City argued that the message that consumers took away was often just that they could be recycled through readily-available curbside recycling programs (which they cannot). Philly also expressed serious concerns that, even if consumers do understand that they need to drop off their plastic bags as specific stores that will accept them (and they're able to find places to do that), consumers will still be misled – because the rate at which plastic bags are recycled – after being collected properly – is still very low, due to the low commercial value of recycled material made from plastic bags.

As Philly asserted in the complaint, "although plastic bags may be 'theoretically' or "technically recyclable," those are merely academic concepts devoid of significance for consumer behavior or the environment."

While this case is still at its very early stages, and it's far too soon to tell how it will be resolved, it certainly does raise some important questions for advertisers to consider as they are making "recyclable" claims for products that aren't recyclable through curbside recycling programs.

First, according to the FTC's Green Guides, in order to make an unqualified "recyclable" claim, the product should be collected through an established recycling program that is available to a substantial majority (at least 60%) of consumers or communities where the item is sold. When there are significant limitations about how the product can be recycled, any recyclable claim should be clearly and prominently qualified to explain what the actual recycling situation is.

Second, when you're making a qualified "recyclable" claim, consider whether reasonable consumers will actually understand the claim that you are making. If you're prominently promoting recyclability, and then in smaller type, or in words that may not be super clear, you're explaining that the product can only be recycled at specific locations, you'd better make sure that this message clearly comes across. At least in Philly, there's a lot of skepticism about whether consumers understand what is being explained to them on the packaging.

Third, it's not enough to just explain that a product is only recyclable through store drop-off programs. As the FTC explains in the Green Guides, those drop-off programs still need to meet the "substantial majority" standard. In other words, even if you've clearly explained that the product must be brought back to the store for recycling, you'd better make sure that the stores are located in a substantial majority of communities where the product is sold.

Fourth, an advertiser could, in theory, offer more limited recycling programs, but, again, the advertiser is going to have to ensure that consumers understand what those limitations are.

Finally, Philly's lawsuit raises the question that the FTC had also raised in the Talking Trash workshop that it held as part of the Green Guides review: is it enough that the product is "recyclable," or should advertisers have to substantiate that the recycling facilities actually do recycle the products? If that becomes the standard some day – and there's no telling if it will – that could dramatically change the landscape of the type of "recyclable" claims that advertisers can make.

This alert provides general coverage of its subject area. We provide it with the understanding that Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz is not engaged herein in rendering legal advice, and shall not be liable for any damages resulting from any error, inaccuracy, or omission. Our attorneys practice law only in jurisdictions in which they are properly authorized to do so. We do not seek to represent clients in other jurisdictions.