- within Cannabis & Hemp, Law Practice Management and Criminal Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

Labour's Employment Rights Bill has been described by deputy prime minister, Angela Rayner, as the biggest change to worker rights in over a generation.

Rightly, much attention has been paid to enhancements in employment rights such as extending unfair dismissal to the first day of employment. Much less attention, however, is paid to how effective legal systems are in enabling the enforcement of these rights. It is one thing having legal protections, but these can be illusory for workers if enforcement is too costly or difficult.

In this insight, we collaborated with our Ius Laboris colleagues around the world to compare the British experience with the experience of litigants in 20 other jurisdictions. To do this we used two hypothetical but commonplace scenarios to map claims in the different countries - the first a straightforward performance dismissal and the second a more complex sexual harassment claim.

Scenarios

Scenario 1: An account executive at an advertising agency paid £50,000/equivalent in local currency. Employed for five years. 35 years old. Dismissed for poor performance. The employeeworks their three months' notice period. Only claimant and one witness for employer to give evidence.

Scenario 2: Same employee resigns and alleges campaign of sexual harassment over several months by line manager. Six witnesses.

The results demonstrate that enforcement in some places is much easier than others, where practical barriers mean rights are often unenforced. For the employer, a common issue is that the costs and reputational damage involved in defending claims push employers to settle cases which have little prospect of success.

Labour courts

In almost every jurisdiction, employment cases are, at least in the first instance, adjudicated by specialist labour courts. In Britain, these labour courts are called employment tribunals. Denmark is an exception where claims are brought in the ordinary courts. In Singapore, employment claims can be brought in the quicker and simpler Employment Claims Tribunal (ECT)

where compensation is capped at around £11,700. Claims for higher sums must be brought in the ordinary courts.

In many places, appeals are to ordinary courts. In Britain, any appeal is to the Employment Appeal Tribunal, a specialist employment court. The nature of these labour courts varies. In most, the judge is legally qualified, even if supported by lay adjudicators. Examples of countries where cases are adjudicated without legally qualified judges include Ireland and New Zealand.

Countries vary in their approach to conciliation or mediation before any claim proceeds. In some, for example, Australia, Italy, Mexico, New Zealand, Singapore (ECT), Spain and Sweden, some form of conciliation or mediation is mandatory. In others, it is encouraged but not obligatory, with examples including China, Denmark, Hong Kong, Ireland, Israel, Korea and the UK. In some countries, it is not available or common.

The process also differs from country to country. Those familiar with the British system will be aware that much of the cost arises from two key steps in the process - the disclosure exercise where all relevant documents must be identified and disclosed to the other party (and a party can apply for orders that the other party must disclose documents which have not been provided), and the preparation and exchange of witness statements.

However, perhaps surprisingly to those familiar with the British system, the same is not universally the case. In some countries there is no obligation to disclose all relevant material, and parties are free to restrict themselves to documents favourable to their case.

As far as witness evidence is concerned, in some countries, statements must be exchanged in advance of any hearing to give each side an opportunity to understand the other's case and evidence. In others, no statements are exchanged beforehand, and even the identity of witnesses need not be disclosed, giving a degree of unpredictability.

In most countries, witnesses can be questioned by both the judge and by the opponent/their lawyer – an adversarial system which also involves some investigation by the adjudicator. In contrast, in some jurisdictions witnesses don't give evidence in person as a matter of course. The adjudicators must rely on written statements and there is generally no cross-examination of witnesses. Examples of this system include Belgium, Korea and France.

For those familiar with the British system, there will be concern at how effective a hearing can be without mandatory disclosure of relevant documents and without cross-examination of witnesses. British employment lawyers will ask how justice can be achieved if parties can withhold documents relevant to the case – that "smoking gun" may go unseen. They may also ask, if there is a conflict of factual evidence between two witnesses, how can a judge possibly evaluate who is correct without questioning the witnesses in court?

However, those familiar with the simpler legal systems may well question the way that the costs and time involved in treating employment claims like civil court claims creates an often-insurmountable barrier to justice, particularly in more complex cases like our scenario 2. What is the point of conferring employment rights on workers if the cost, financial risk and practicalities of enforcement render them irrelevant to all but the richest of litigants.

Claims

In this insight we have used two common scenarios.

Scenario 1

The first involves a performance dismissal where the employer has terminated employment with limited process, but where there is no suggestion of any unlawful discrimination or other factors at play. Notice pay is paid.

In most jurisdictions, employees have the right to challenge such a dismissal. In the UK, for example, the claim would be for unfair dismissal. However, in most states in the US, there is "employment at will" – which means that in most cases no remedy exists for an arbitrary dismissal or one where no process was followed. In Singapore, certain common law claims can be brought but damages will rarely be available if notice pay is paid.

Scenario 2

The second scenario involves a claim for sexual harassment which it is alleged has continued for some time and has led to the claimant feeling that they have no alternative but to resign (a constructive dismissal). The more complicated factual background and the number of witnesses involved means that this will generally be more time-consuming and costly for both parties to litigate. The potential reputational issues are also likely to weigh more significantly on the parties.

In most jurisdictions, the claimant will have a clam for unlawful discrimination/harassment. However, in Mexico and China, the only claims arise from the constructive dismissal. In Singapore no harassment claim can normally be brought against the employer, but one can be brought against the manager personally. In that jurisdiction (as well as others), a claim for breach of its duty of care could be brought against the employer for failing to provide a safe working environment. In other jurisdictions, such a claim would be rare as an effective remedy is available under harassment/discrimination laws.

In Denmark, a separate claim to the one of discrimination/harassment in scenario 2, can be brought in a specialist Board of Equal Treatment against the employer for failing to have prevent the harassment from occurring. Compensation for this separate claim is limited to 13,500 EUR. Unlike the other claims which might be brought in Denmark, this claim would be procedurally much simpler as it is determined only on written evidence and no fee is payable to bring the claim (see below).

Costs

For claimants, the costs involved in pursuing an employment claim comprise court fees and lawyers' (or other paid representatives') costs.

For employers defending clams, the costs will be their lawyers' fees but also the often-considerable management resources which can be sucked into defending the case. The costs are likely to be higher in complex cases such as scenario 2, where employers will have to deal with the disclosure of extensive documents and are likely to have more relevant witnesses.

Employees can complain about the unequal playing field where they must bear VAT on their legal costs and pay fees out of untaxed income whereas the position is often not the same for the employer. This is a common complaint in France, by way of example, as well as in the UK.

Court fees

In some cases, no court fees are payable at all, and in others a nominal sum is payable. Britain did have a system of fees for a few years, but the Supreme Court declared these unlawful in 2017 as they prevented access to justice. Sweden and Denmark are outliers with higher fees to file claims, but even in those countries, fees to start a claim are not that large and amount to no more than £200 (in Denmark further fees of up to 2,000 EUR will be payable prior to the final hearing depending on the value of the claim).

In Germany, liability to pay the fee between clamant and employer is determined at the end of the case by the labour court depending on the outcome.

Legal costs

In most jurisdictions, both employee and employer will commonly be represented at the labour court by lawyers or other professional representatives. Trade union representatives may represent members of the union. Unqualified representatives such a HR consultants will also represent employers in some cases.

In our two scenarios, in some jurisdictions, the employee is less likely to be represented in straightforward cases such as scenario 1 and may represent themselves instead, with Poland and Britain being examples. Legal representation is more likely in more complicated claims, such as scenario 2, where the compensation payable and reputational risks are likely to be greater. However, in Britain it is still quite common for individuals to represent themselves in complex claims due to the lack of affordable legal representation. New Zealand is another example of a country where claimants are often not legally represented even in more complicated cases.

In some places lawyers may advise behind the scenes but won't appear before the labour court. Hong Kong and Singapore (ECT) are examples. In Korea, it is common for licensed labour consultants to represent parties before the labour court.

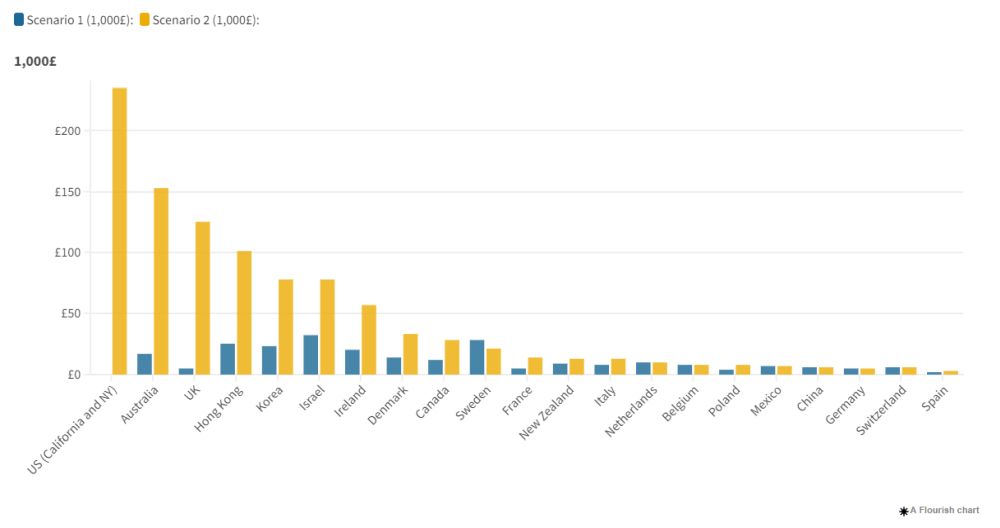

Highlighting the barriers to enforcing claims in some jurisdictions, claimant legal costs can vary enormously. The graphs below set out typical costs, although these can be higher or lower depending on the circumstances of each case. For example, disputes about disclosure of documents can lead to preliminary hearings, delaying the case and adding significantly to costs. Other cases can run smoothly and have lower costs.

Legal costs of pursuing a claim

Legal costs of defending a claim

Israel and the US are not included for costs of pursing claims as contingency fees are the norm. Singapore and US are excluded as far as scenario 1 is concerned as claims are either unavailable or unlikely to result in compensation respectively.

It should be noted that in scenario 2, in China, Mexico and Singapore, the available claim against the employer is for wrongful constructive dismissal only so not an equivalent comparator with the discrimination/harassment claims in other jurisdictions. We have therefore excluded from the comparative charts for scenario 2.

These graphs highlight the practical obstacle of affordability for claimants in some jurisdictions in enforcing rights as well as the costs for employers in defending clams. It illustrates the huge disparity in affordability between different countries as well as, in some but not all cases, the huge difference in costs in enforcing or defending more complex cases in comparison to simpler cases.

Legal aid is not available to claimants in most cases, but it is available in several countries. Usually this is means tested, and it can be available making the enforcement of rights much more realistic. China, Germany, Israel, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Korea, Spain and Switzerland are examples of places where legal aid is realistically available. Mexico has a system of public defenders available to employees.

Assistance can also be available from human rights or equality commissions in discrimination cases, such as our scenario 2. New Zealand is an example where funding is readily available through the Office of Human Rights Proceedings. In countries such as the UK and Ireland funding is theoretically available but limited resources mean that claimants can rarely call on support unless an issue of public importance is at stake.

In the US, Mexico and Israel, contingency and success fees are common - reducing the potential costs to claimants but resulting in any award of compensation being split with the lawyers. Occasionally, in some jurisdictions, potential claimants may benefit from insurance which covers their legal fees.

The successful party can, in some places, recoup at least of some of the costs incurred from the unsuccessful party, but this is almost always far less than the actual costs incurred. Examples include Belgium, Canada, Hong Kong, Denmark, Israel, Italy, Netherlands, New Zealand, Poland, Spain, Sweden and Switzerland. In a handful of others such as China and Britain, costs are theoretically available but only awarded in exceptional circumstances.

Recouping costs can be a double-edged sword for claimants. On the one hand, the ability to claim one's own costs if the case is successful (even if only in part) can encourage claimants. However, on the other hand, for a claimant this may represent a significant disincentive to enforce their rights if reimbursing even part of an employer's legal costs might be prohibitive.

Public hearings

In almost all cases, labour courts are public. Israel is an exception as is Singapore for claims brought in the ECT. However, there is an increasing tendency around the world for hearings to be conducted by video instead of in person though, to date, the practice is variable.

For both parties, a deterrent to litigation is the significant reputational risk caused by the public nature of the hearing. This is particularly an issue in cases such as our scenario 2, where allegations of harassment may attract considerable press or public interest – and potentially damage the employer's reputation even if the claim is successfully defended. In most cases, all full judgments are also published on a publicly accessible database, meaning that it is possible to search for cases involving particular employers months or even years later. This is the case in countries such as Canada, New Zealand, Ireland and the UK. On the other hand, France and Hong Kong are examples of places where only a few tribunal judgements are currently available on a publicly available database. Steps are being taken in France to extend this eventually to all tribunal judgement but even then without the names of natural persons. So, in our two scenarios, the names of the employer would be published but not the names of the clamant bring the claims.

Timing

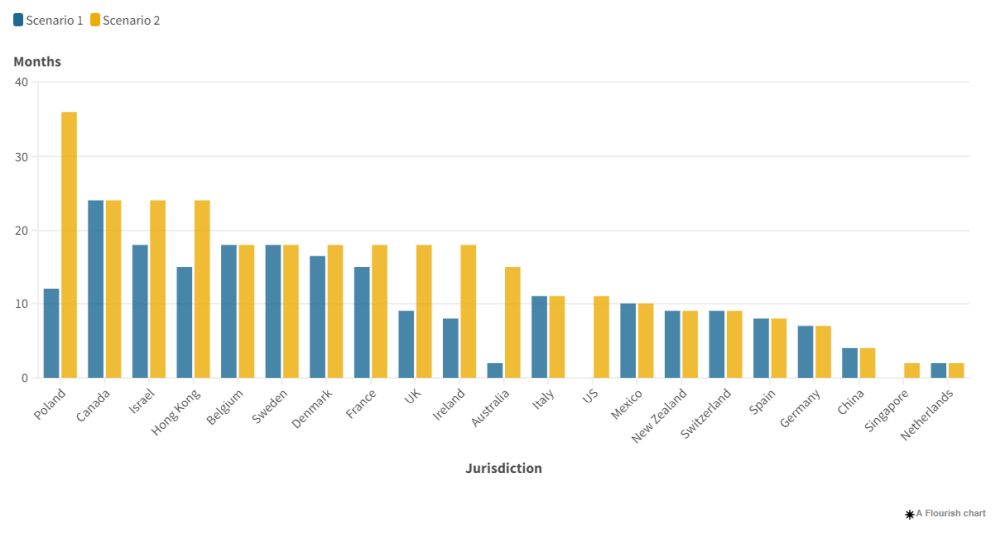

One barrier to an effective dispute resolution of employment cases is the time it typically takes from filing a case to proceeding to an outcome.

This varies significantly, and largely reflects the country's approach to more complex procedures such as mandatory disclosure or advance exchange of witness statements. The delays in the system in Britain have increased significantly in recent years, with backlogs related to the covid-19 pandemic and a lack of resources for the tribunal system. However, the British delays are not the longest. Even simple cases like scenario 1 can typically take two years in Canada, and more complex cases like scenario 2 typically take three years in Poland. Such delays are a real barrier to effective enforcement of rights whatever the substantive law might say.

Whilst the delay to a hearing in a case like scenario 1 is typically only a couple of months in countries such as Netherlands, Korea and Australia, it will typically be 18 months or more even for a simple case in countries like Sweden, Israel, Canada and Belgium. In our scenarios the wrongful dismissal claim in scenario 2 would often be heard in Singapore (ECT) within a couple of months.

Average time to a final hearing

More complex cases predictably can take much longer in many countries to get to a hearing as shown with our second scenario. Poland, the UK, Ireland, Hong Kong and Australia are examples of much longer delays in complex cases. In some other countries, however, these more complex cases take no longer to get to a hearing than the simpler cases. Once parties get to a hearing, the likely duration of that hearing also varies.

In scenario 2, the typical hearing length varies greatly, reflecting the very different approaches in different countries. In some countries, even a sexual harassment complaint of this nature will be heard in half a day or less – Belgium, Germany, Italy, Netherlands and Switzerland are examples. At the other extreme in Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Israel, Poland, Britain and the US, a case of this kind typically takes four or five days or even longer. It is no surprise that in those countries the legal costs are generally much higher.

In scenario 1, the variation is somewhat less pronounced. The same list of speedier jurisdictions will see the hearing normally completed in half a day or less. In countries where hearings tend to be longer, a simpler case such as this would typically take around two days. This list includes Australia, Canada, Hong Kong, Israel and Sweden. In Britain, the parties could expect the hearing in a scenario 1 case to be completed in a day, or two at the most.

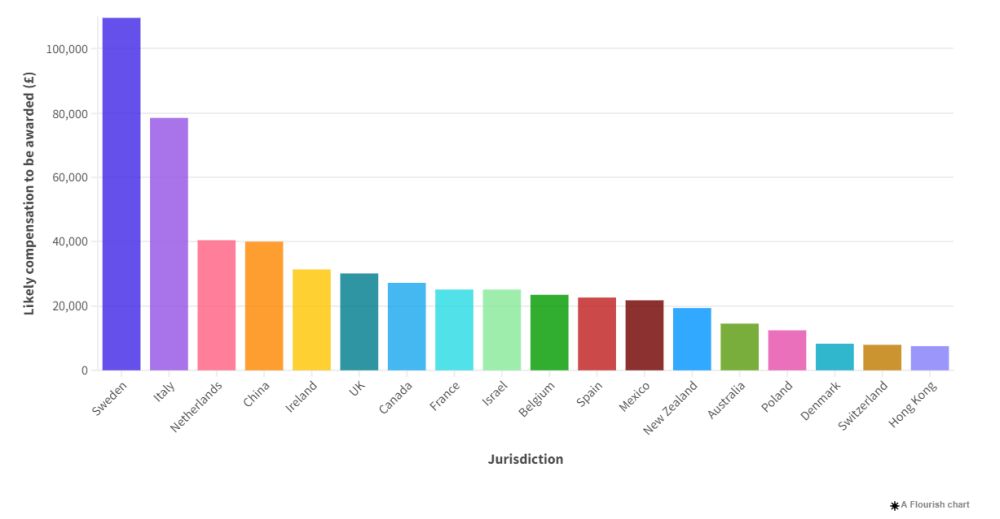

Compensation

Another factor which differs from country to country is the likely compensation payable in a typical case, noting that there are a wealth of factors which will influence the level of awards on a case by case basis, making comparisons more difficult.

Taking our first scenario, the typical compensation payment varies from £110,000 in Sweden to less than £10,000 in Switzerland and Hong Kong, significantly impacting the extent to which the law deters arbitrary dismissal or the absence of any process.

Likely compensation - scenario 1

In most cases, the remedy sought is one of compensation. In others, there is at least in theory the possibility of claiming reinstatement. In Britain, reinstatement is theoretically the main remedy for an unfair dismissal, but this is very rarely ordered in practice. In a small number of countries, reinstatement is the only or most likely remedy. These include Germany and Korea (so excluded from the compensation chart above for scenario 1). The US and Singapore are excluded in the absence of unfair dismissal laws in those jurisdictions.

In our second scenario, compensation payments are typically much higher and may include punitive damages and injury to feelings/personal injury as well as financial loss. China, Mexico and Singapore are excluded as the compensation payable by the employer is because of the constructive dismissal and not harassment/discrimination.

In Belgium, an additional award of £25,000 (6 months' pay on the facts of scenario 2) may be paid by the accused individual personally. In most jurisdictions, including the UK, an additional claim can be brought against the accused individual and an award made against them personally.

Many of the surveyed countries are in the EU, where a cap on discrimination compensation payments would be unlawful. In these cases, higher compensation is more typically awarded. In the UK, the US, Israel, Ireland and Italy awards of more than £75,000 (18 months' pay on the facts of scenario 2) are common. Nonetheless, claims are typically low in other countries, notably Belgium and Korea.

Likely compensation - scenario 2

Conclusion

British litigants face delays of two years or more before a final hearing. The costs of pursuing or defending claims can dwarf the likely awards and represent a probative barrier for many prospective claimants. The stress of all-consuming litigation can quickly wear down the most resilient of claimants. The management time and legal fees spent on defending claims will often push employers towards resolving disputes long before any hearing.

No wonder that, in the vast majority of cases, claims are settled early in order to avoid the cost, stress, management time and unpredictability of litigation. It is also true that some claimants understand the pressures on employers to settle and will bring unmeritorious claims in search of a quick pay off.

Is there a better way? Our analysis shows that whilst delays are amongst the longest in Britain, it is far from alone in seeing cases taking well over 12 months to reach a hearing. Legal costs can also be great in many countries, particularly when defending more complex cases like our scenario 2.

Britain's employment tribunals (previously called industrial tribunals) were first established over 50 years ago as a simple mechanism to resolve individual employment disputes without the need for lawyers. Half a century later, employment law has mushroomed into a complex set of rules which parties need legal support to navigate.

More resources to reduce delays would be welcome but seem unlikely in today's straitened times. Some would argue that an increased role for trade unions in the workplace could contribute to reduced pressure on employment tribunals. A greater role (and resources) for government agencies in investigating and enforcing systemic issues such as workplace discrimination is another way forward which has much merit. A possible model is the role of the ICO in enforcing data privacy rights in the UK.

A start would be for governments and policymakers to focus as much on the practical enforcement and defence of workplace claims as on the substantive rights themselves. Perhaps useful lessons could be learnt from the approaches taken in other jurisdictions.

The authors gratefully acknowledge the input into this insight of the following lawyers:

- Corrs Chambers Westgarth, Australia

- Claeys & Engels, Belgium

- Mathews Dinsdale, Canada

- Fangda Partners, China

- Norrbom Vinding, Denmark

- Capstan Avocats, France

- Kliemt,HR Lawyers, Germany

- Lewis Silkin, Hong Kong

- Lewis Silkin, Ireland

- Herzog Fox & Neeman, Israel

- Toffoletto De Luca Tamajo, Italy

- Basham, Ringe y Corea, Mexico

- Bronsgeest Deur Advocaten, The Netherlands

- Kiely Thompson Caisley, New Zealand

- Raczkowska, Poland

- Rajah & Tann, Singapore

- Sagardoy Abogados, Spain

- Elmzell Advokatbyra, Sweden

- Blesi & Papa, Switzerland

- United States, Sheppard Mullin

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]