In Issue 13 of Inside Arbitration we explored the efforts of the international arbitration community and beyond to improve gender diversity, particularly among arbitrators. The arbitration community has also acknowledged the need to focus on other forms of diversity – in particular ethnic, racial and cultural diversity. Institutions have begun to monitor the nationality and place of qualification of arbitrators, but efforts in this sphere are at a much more fledgling stage. Despite these efforts, change is slow. The statistics for party and co-arbitrator appointments of female arbitrators remain stubbornly low.

The LCIA's Casework Report for 2022, which was published in June of this year, showed a decrease in the percentage of women selected by the parties (19%, albeit up from 16% in 2021) and co-arbitrators (23%, down from 33% in 2021). These low percentages of female arbitrators selected for party appointment are replicated across other main arbitral institutions including HKIAC (18.9% in 2022) and the ICC (16% in 2021). For many, this lack of diversity is seen as evidence of gender discrimination in the field of arbitration.

In September 2022 the Law Commission of England & Wales (the Law Commission) made a bold intervention into the discrimination debate in the context of its review of the English Arbitration Act 1996 (the Act). In its first consultation paper the Law Commission asked whether the Act should prohibit discrimination in the appointment of arbitrators (specifically looking at arbitration agreements which specify the characteristics of potential arbitrators). However, in its second consultation paper in March 2023 it identified new topics of potential reform. Rather than focusing on the question of arbitrator appointments and gendered language, the Law Commission opened up the scope of review to consider whether "discrimination should be generally prohibited in the context of arbitration".

This novel proposal was superficially attractive. A legislative stance would send a strong message that discrimination in the arbitral process is not to be tolerated, supporting diversity and access to a broad pool of talent. However, the Law Commission set out no detail in its paper about how discrimination (including in the appointment of arbitrators) would be prohibited, what a "general" prohibition on discrimination would look like, or the legislative changes required.

While the proposal has not made its way into the Law Commission's final paper on proposed changes to the Act, it raised an interesting question: is legislating to prohibit discrimination realistic? In this article we explore some of the practical challenges and questions that need to be answered before any such prohibition would be effective.

How would a prohibition work in the context of arbitrator appointments?

When a company hires a new employee, they will usually follow a strict recruitment process with a detailed job specification, an application process, a degendered review of applications, a shortlist of candidates, and a carefully structured interview to test candidates' aptitudes, competencies and suitability for the role.

However, the appointment process for arbitrators follows a very different pattern. Arbitrators are either appointed by arbitral institutions, or nominated by co-arbitrators or by parties, usually with the advice of their legal counsel.

1. Appointment by parties

When choosing who to appoint, parties are highly unlikely to write any sort of public job specification, rather they may simply identify in their own minds the key characteristics needed such as someone qualified in a particular jurisdiction, with experience in a particular sector or with strong case management skills. Subjective criteria might also be applied to the appointment. For example, whether or not the party's legal counsel has experience of the arbitrators being considered. In an institutional arbitration, the institutions do not generally question the basis for the party's nomination, or how they arrived at their choice, before making an appointment (although perhaps this is starting to change, with new diversity provisions in the Scottish Arbitration Centre which apply to both the parties and the institution itself). Generally though, any arbitrators being considered for appointment are very unlikely to know this. In most cases, only the final few potential candidates may be approached to provide information about conflicts or availability. Even were a potential arbitrator to know they were being considered, for example by making a data subject access request, any such correspondence between clients and their counsel may be covered by privilege or professional secrecy laws (except for limited exceptions).

2. Appointment by arbitral institutions

Arbitral institutions retain databases of potential arbitrators which are added to and curated by the institutions' secretariats. The process by which a potential arbitrator is added to the database is often not transparent. Each institution will have their own system for choosing appropriate arbitrators, usually in discussion with their Court or board who will consider the necessary experience and expertise. Candidates will not know they are under consideration until they are approached for their availability and any conflicts of interest. The parties will also be asked to identify any potential conflicts or issues with the proposed candidates. Some arbitral institutions may propose a list system which requires each party to rank their preferred arbitrators from a list. The institutions do not set out the basis on which the list has been prepared, nor are the parties required to justify the rankings they give for those candidates.

Unlike appointments by parties, an arbitral institution's appointment process would be unlikely to be covered by privilege or professional secrecy. Arbitral institutions currently have immunity under s74 the Act, save for acts or omissions shown to have been made in bad faith. In order for the prohibition of discrimination to be effective, there would need to be clarity around whether or not immunity applied or whether "bad faith" would be made out if discrimination were proven.

3. Appointment by co-arbitrators

Many arbitration clauses provide that the two party-appointed co-arbitrators choose a suitable presiding arbitrator of the arbitral tribunal. Some co-arbitrators will seek the views of the parties before making their choice. Others will simply propose a name and seek confirmation from the parties that there are no conflicts of interest. The appointment process here is not transparent and different co-arbitrators may adopt different processes.

As with arbitral institutions, the appointment process would be unlikely to be covered by privilege. Similarly, arbitrators currently have immunity under s29 of the Act, save for acts or omissions shown to have been made in bad faith. Again, in order for the prohibition of discrimination to be effective, there would need to be clarity around whether or not immunity applied or whether "bad faith" would be made out if discrimination were proven

Realistically, the effective prohibition of discrimination in arbitration would require creating processes for the appointment of arbitrators that are sufficiently transparent for the necessary evidence of discrimination to be available. This could include adopting similar steps to a recruitment process for anyone involved, whether parties, institutions or co-arbitrators. This will be seen as unworkable by many in the context of arbitration for reasons of efficiency and practicality. Few parties would want to publicise their disputes in order to ask arbitrators to apply for the role. Any interview of a potential arbitrator candidate must necessarily be limited and carefully carried out so as to minimise the risk of challenge to the arbitrator's independence and impartiality.

Who would face discrimination claims?

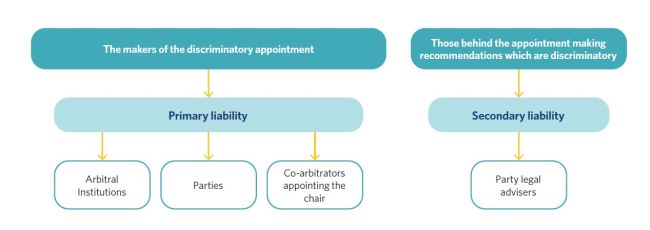

Assuming that a discrimination claim could be made out by a potential arbitrator, who would the claim be directed at? As we have already explored, arbitrator appointments can be made by arbitral institutions, co-arbitrators and parties. In the latter case, parties are advised by their legal counsel in deciding who to select. While the client may make the final decision, they will often be guided by the recommendations of their counsel and any bias inherent in their counsel's shortlisting process.

Critically, the Law Commission did not address whether or not liability for discrimination in the arbitrator appointment process would be restricted to primary liability or whether secondary liability would also apply as described in the diagram below.

Resolving a discrimination claim: remedies and wider impact

Assuming a potential arbitrator was to bring a claim, in which forum would they do so and what remedies would they be seeking?

The Equality Act 2010 allows claims to be brought before the Employment Tribunal, the County Courts or the High Court in certain circumstances. In the context of arbitration, the only realistic option would be for such claims to be determined by the High Court. The current backlog before the Employment Tribunal stands at approximately one year and there is no availability for expedited hearings, which would limit the availability and impact of non-monetary remedies described below. Resolution of discrimination claims by the High Court would ensure that the decision-maker had experience and understanding of arbitration and the arbitrator appointment process. Consideration would also need to be given to whether such claims would be public.

Under the Equality Act, the remedies for discrimination claims are a declaration of rights (which includes a declaration of unenforceability, which can in turn include a declaration as to the unenforceability of a term of a contract (s142)); compensation for loss of earnings and injury to feelings; or a "recommendation" to take certain steps to undo the discriminatory action. However, some of these remedies within the existing employment law framework are unlikely to be appropriate for arbitration.

- Arbitrator characteristics or requirements which are discriminatory will rarely be included as contractual terms (of the arbitration agreement or of the arbitrator appointment) meaning there would be no terms to declare unenforceable.

- Recommendations, particularly a recommendation that the arbitrator appointment process be re-run, would require the discrimination claim to be brought and heard on an expedited timescale to avoid derailing the arbitration. Recommendations also cannot be enforced. Given that arbitration is a party-led, contractual process, it would seem very unlikely that parties would accept the replacement of an arbitrator who is already in place, even if such a step were "recommended". This is particularly the case if giving effect to the recommendation would result in an impact on the wider arbitration.

It would be important to ensure any decision-maker determining a discrimination claim could exercise discretion in favour of ensuring an effective and efficient arbitration process when considering appropriate remedies, avoiding a protracted parallel discrimination claim running alongside the arbitration proceedings. Practically, this is likely to mean that most remedies would be financial in nature (s124(7) of the Equality Act), compensating the potential arbitrator for their loss of earnings (if applicable) and the injury to their feelings.

Could a general prohibition work?

Discrimination in the arbitration process is plainly harmful, not only undermining the right of each individual to be treated equally regardless of characteristics such as race, ethnicity and gender, but also narrowing the pool of arbitrators to the detriment of the parties. The impact of multiple efforts to encourage diversity within arbitration appears to be slow. However, there are considerable challenges in legislating against discrimination in the appointment of arbitrators. These challenges are writ large when we consider the Law Commission's broader suggestion of a "general" prohibition on discrimination in arbitration.

- Whose conduct should be regulated? Would a general prohibition on discrimination only cover discrimination by arbitrators within the process (once appointed), institutions and parties? Or would it also cover discriminatory acts by other participants like legal counsel, witnesses and experts, or between arbitrators in arbitrator deliberations? The Act does not currently contain any duties on these other participants. This would be a significant change in approach with potentially wider consequences than just discrimination.

- Should the prohibition only cover direct discrimination? Direct discrimination involves treating someone with a protected characteristic less favourably than others – for example, where an arbitrator dismisses or denigrates the contribution of a female advocate. Indirect discrimination involves putting rules or arrangements in place that apply to everyone, but that put someone with a protected characteristic at an unfair disadvantage. The Law Commission's consultation appeared to envisage covering only direct discrimination. However, most discrimination in an arbitration context may well be indirect. Would legislating against direct discrimination alone achieve enough to merit legislative intervention?

- What protection is already on offer? There are already many protections offered by the Act that could potentially cover discriminatory conduct. An arbitrator could be challenged and removed by the parties under s24 on the basis that they are not fulfilling their duty to the parties (s33) by acting in a discriminatory manner. Similarly, discriminatory behaviour in the arbitral process could lead to a challenge to an arbitral award under s68. For English-qualified barristers and solicitors, discrimination is prohibited as part of their professional conduct obligations and under s44 to 47 of the Equality Act. Consideration would need to be given to the gaps within the existing framework. As already discussed, the existing provisions on immunity for arbitrators and institutions may need to be revisited.

- Is legislation the most effective solution? If gaps do exist, we must ask whether the Arbitration Act is the right tool through which to introduce new legislation, or whether this should be done through amendments to the Equality Act or by way of guidance.

- What could be the wider implications? The Law Commission would also need to consider how amending the Arbitration Act may have implications for how London is regarded as a seat of arbitration internationally. For example, parties may be concerned about the risk of satellite litigation. They may also fear a potentially discriminatory appointment or discrimination within the arbitration itself could lead to a challenge for procedural irregularity. Moreover, parties may worry that an award rendered by a tribunal which has not been constituted in accordance with party agreement (because such agreement was considered discriminatory at the seat) could make the award unenforceable elsewhere.

Conclusion – More to be done

In this article we have given some thought to the challenges of implementing workable and effective legislation against discrimination in arbitration. Many of these challenges result from the unique position of arbitration as a contractual, party-driven process yet one that is regulated by domestic legislation and the judicial oversight and support of national courts. It also cannot be viewed purely through a domestic lens. The Act forms part of a wider international system backed by treaty which requires the appreciation of other viewpoints and approaches from across the globe, balancing domestic agendas with the application of those agendas on a perhaps less receptive international user-base. Given these complexities, it is unsurprising discrimination has not been addressed in arbitration legislation to date.

In early September the Law Commission concluded, with some reluctance, that a prohibition on discrimination would be unlikely to be effective and could well give rise to satellite litigation and disingenuous challenges. Many participants in the arbitral process will find themselves simultaneously disappointed and relieved that the Law Commission has not progressed this proposal and discrimination has not made its way into the draft bill to be placed before Parliament. However, the fact that this topic was raised should give all participants in the process pause for thought and a renewed focus on improving diversity in arbitration. The warning bell has been sounded for participants in the arbitration process: if we don't solve the problem ourselves, governments across the world will do it for us.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.