- within Intellectual Property, International Law and Tax topic(s)

- with readers working within the Aerospace & Defence, Media & Information and Metals & Mining industries

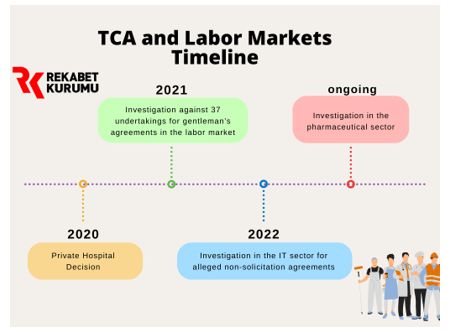

In recent years, labor markets have fallen under the watchful eye of competition authorities, with the Turkish Competition Authority ("TCA") taking the lead in intensifying its investigations in this sector. With three investigations already under its belt and hefty fines totaling approximately 11 million USD, the TCA shows no signs of slowing down, with an ongoing probe into HR practices within the pharmaceutical industry. The TCA's laser focus on labor markets has sparked a growing demand for clarity and guidance among firms. In response, the TCA has been hard at work developing a draft Guideline to address these needs, culminating in a recent conference open to industry representatives. The long-awaited news arrived in the past weeks when the "Draft Guideline for Competition Violations in Labor Markets" was unveiled to the public for feedback. While it remains uncertain to what extent the Guideline may change following the public consultation, in its present form, it serves as an indication of the TCA's assertive and active approach in this domain.

TCA and Labor Markets

The first penalty imposed by the Competition Authority for violations in the labor markets came with the Private Hospital Decision taken during the pandemic period. In the relevant investigation, TCA concluded that certain private hospitals restricted competition in the labor market by preventing employee transfers and/or determining the salary scale of employees1 . The Private Hospitals decision was followed by an investigation launched in 2021 against 37 undertakings across Turkey for alleged gentleman's agreements in the labor market, an investigation in 2022 in the IT sector for alleged non-solicitation agreements, and an ongoing investigation in the pharmaceutical sector2 . These recent developments exhibit a clear distinction from the previous decision of the TCA in labor markets, as it preferred not to launch an investigation or impose monetary fines in its early decisions. However, there has been some uncertainty about the approach of the TCA to those markets, particularly on the practices which are not hard-core restrictions and may have also benefits on the market. Non-solicitation clauses, information exchange, third party involvement and benchmarking activities stand out among the issues need such a clarification. Additionally, due to the recent high inflation rates in Turkey, the wages are needed to be adjusted more frequently. This circumstances also increased the benchmarking and information exchange. In this vein, Draft Guideline is expected to resolve those uncertainties and shed the light for the companies for their future practices.

The Draft Guideline begins by identifying certain market characteristics. It states that wages and working conditions in labor markets are determined by the bargaining power of both employees and employers, with a significant imbalance favoring employers. The guideline emphasizes that this imbalance is particularly noticeable in highly concentrated sectors, which increases the likelihood of employers engaging in anti-competitive behaviors. Furthermore, the Draft Guideline notes that employees' reactions to changes in wages and working conditions are generally weak, as changing jobs entails financial and emotional burdens. As a result, employees tend to tolerate unfavorable conditions and exhibit reduced job mobility. It also mentions that legal tools, such as non-compete agreements, further restrict employees' ability to move between employers. These findings, which underscore the particularly weak position of employees compared to companies, also shape the approach outlined in the Guide.

Competition Violations in the Draft Guidelines and General Approach

The Draft Guidelines address agreements or practices between employers that aim to restrict the movement of labor in the market or set fixed wages and working conditions for employees. This kind of behavior, along with decisions and practices of business associations, is considered a violation of competition law. The focus of the Draft Guidelines is primarily on wage-fixing and employee no-poaching agreements, but it also covers restrictions on information exchange and ancillary restraints in this market. Please refer to the following section, where we will examine the specific headings of the Draft Guidelines and provide an overview of the general approach. The following sections dive into the specific headings of the Draft Guidelines and outline the general approach.

Wage Fixing Agreements

Draft Guidelines defines wage fixing agreements as "where undertakings jointly determine the working conditions of their employees, such as wages, wage increases, working hours, fringe benefits, indemnities, physical working conditions, leave rights, and non-competition obligations". The guidelines state that when companies jointly determine certain working conditions, it constitutes an infringement under the Competition Act. It is important to note that the definition of wage fixing agreements is broad, encompassing more than just wages and fringe benefits, and including working hours or working conditions. The agreements related to any element within this broad definition are accepted to restrict competition, regardless of their effects.

The Draft Guidelines also address the involvement of third parties in wage fixing agreements, stating that third parties may be liable if they broker the agreement. However, there is no clarification on the role of labor unions and collective labor agreements concluded through them. Considering the importance of trade unions and wage negotiations in protecting workers' rights, the guidelines' scope of third-party activities that constitute violations remains unclear, although it is considered that the third parties meant by the Guidelines are not labor unions.

Non- Poaching Agreements

The Draft Guidelines define employee non-solicitation agreements as "agreements, directly or indirectly, by one undertaking not to offer employment to, or not to hire, employees of another undertaking". However, it states that an employee non-poaching agreement may also exist where undertakings do not completely prohibit each other from offering employment to or hiring each other's employees but make employment subject to the approval of each other or the approval of the employee's current employer.

Considering the generally accepted behaviors that have become commercial customs and traditions, the concept of "approval" and the "agreement" needs more clarification. This is because, in practice, it is quite common to ask for references from the former workplace of an employee who wishes to join a new workplace. Whether the positive or negative reference provided by the former workplace will be accepted under the approval mechanism referred to in the Guidelines is still behind the smoke screen. The Guideline also present little guidance on the tools to differentiate the non-solicitation agreements from unilateral no- hiring decisions of the companies, which may base on several factors, other than an agreement. The lack of provisions for such exceptions in the Guideline underscores the TCA's zero tolerance for regulations and behaviors that impede employee mobility.

Information Exchange

Under the Draft Guidelines, information refers to any direct or indirect data related to the labor force, and information exchange refers to the circulation of such information between undertakings. The Draft Guidelines also point out that the exchange of information may take place through a third-party channel such as intermediary institutions and platforms; through associations of undertakings, independent market research organizations or private employment agencies; and through channels such as websites, media, algorithms.

The exchange of information can improve efficiency by reducing information imbalances between businesses. However, the Horizontal Cooperation Guidelines emphasize that sharing competition-sensitive information may outweigh these benefits. In the labor market, sharing details like salaries, pay raise rates, and benefits can reduce uncertainty but also create unfair competition. The guidelines advise against sharing specific, current, and non-public data that could help other companies understand individual data sources, as this could have anti-competitive effects. In this context, exchanging non-aggregated, current and/or forward-looking, non-public information that enables understanding of the data source or individual data content between businesses may lead to anti-competitive effects. The approach taken in the Horizontal Cooperation Guidelines, particularly regarding the exchange of price information, is similar here in terms of fees.

Ancillary Restrictions

Ancillary restrictions have become increasingly important, particularly in the context of investigations within the IT sector. Provisions that restrict the transfer of employees in joint projects or vertical agreements are crucial for safeguarding related investments and ensuring the expected outcomes of the project. These restrictions are also deemed necessary for achieving the objectives of the agreement and are directly linked to these goals, despite not forming the substance of the agreement. The Draft Guidelines assess ancillary restraint based on the following criteria:

(i) Direct relevance

The requirement of direct relevance, as outlined in the Draft Guidelines, signifies that the restriction is inseparable from the original agreement and is essential to its implementation. This condition is pivotal in determining whether a restriction is inherently linked to the original agreement, although its practical implications are yet to be observed.

(ii) Necessity

The necessity condition, as defined in the Draft Guidelines, refers to the existence of a limitation that is essential for the execution or preservation of the original agreement between the parties. However, the guidelines do not provide a specific example of the necessity condition, which is described as a limitation deemed necessary in situations where the original agreement cannot be implemented or maintained without it.

(iii) Proportionality

According to the Draft Guidelines, for a restriction to be considered proportionate, the objective it seeks to achieve must not be attainable through less anticompetitive means, and the scope of the restriction must be limited to the purpose, geographical scope, duration, and parties of the original agreement. The guidelines also offer examples of restrictions that may be deemed proportionate, distinct from the other conditions.

Furthermore, the Draft Guidelines stipulate that the burden of proving the ancillary restriction criteria rests with the parties involved. However, the guidelines do not specify the evidence required for the parties to fulfill their burden of proof in this process. While it is not a requirement for the ancillary restriction to be in writing, the guidelines state that a written restriction would enhance certainty regarding the aforementioned conditions.

Conclusion

In conclusion, the Draft Guidelines represent a significant step towards addressing the need for clarity and guidance in labor market regulations. The increasing scrutiny and stricter approach to examinations in this area have highlighted the necessity for resources that can provide valuable insights. This development marks a crucial milestone in the ongoing efforts to ensure compliance and fairness in labor markets. While the Draft Guidelines acknowledge the types of infringements observed in these markets, it is imperative to differentiate between unlawful activities and legitimate undertakings. On the other hand, it is uncertain, how the Draft Guideline will change after the public consultation, it, with its current version, underscores the proactive stance of the TCA in the enforcement of competition rules into the labor market.

Footnotes

1. TCA decision dated 24.02.2022 and numbered 22-10/152-62.

2. TCA decision dated 26.07.2023 and numbered 23-34/649-218.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.