On 10 September 2024, the Grand Chamber of the Court of Justice of the European Union delivered a landmark judgment in favour of the European Commission in the appeal case C-465/20 against the previous judgment of the General Court in the joint cases T-778/16 and T-892/16, Ireland and Others v Commission. This judgment is a significant contribution to the EU jurisprudence on transfer pricing and the concepts of arm's length principle, functional analysis and the separate entity approach. A key element was the notion of substance, or rather the lack thereof, and the attribution of profits of intellectual property to a permanent establishment was discussed, where the Grand Chamber of the CJEU provided a detailed review of the General Court's analysis and found significant procedural and substantive errors, reversing many of the General Court's conclusions in the original judgment. This article provides a detailed analysis and breakdown of the CJEU's findings.

Background and the Judgment under Appeal

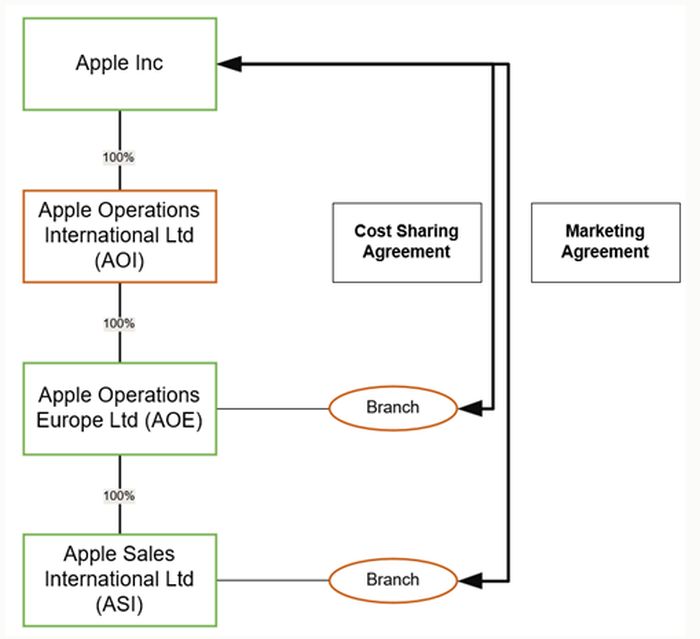

The entities involved in the transfer pricing arrangement at issue are Apple Inc, a US-based parent company, which owns 100% of Apple Operations International Ltd ("AOI"), which in turn owns 100% of Apple Operations Europe Ltd ("AOE"), an Irish incorporated company which is not tax resident in Ireland but has a branch in Ireland. AOE in turn owns 100% of Apple Sales International Ltd ("ASI"), which is also an Irish company, not tax resident in Ireland but with a branch in Ireland.

AOE and ASI had a cost sharing agreement ("CSA") with Apple Inc. under which they shared the R&D costs of the Apple products and IP. Under the CSA, Apple Inc. remained the legal owner of the IP created and the IP was granted royalty-free to AOE and ASI, but they were required to bear the risks, including reimbursing Apple Inc. for the development costs.

In addition, ASI had a marketing agreement with Apple Inc. whereby Apple Inc. provided marketing services to ASI for the creation and development of marketing strategies, programmes and advertising campaigns, and ASI paid a portion of Apple Inc.'s expenses plus a profit margin.

The diagram below illustrates this structure.

Functions of the Irish Branches

The Irish branch of ASI had a number of functions critical to Apple Group's sales and IP exploitation, management and enhancement, including:

- Executing procurement, sales and distribution of Apple products to associate enterprises of the Apple Group and third parties.

- Localization and execution of global marketing strategies.

- Gathering and analysing regional data to predict market demand.

- Operating aftersales customer support and repair service via AppleCare – which lead to assumption of significant product risks by the branch.

- R&D functions performed by 50-60 full-time employees of the branch in Ireland.

The Irish branch of AOE performed a number of critical manufacturing and assembly functions including:

- Development of Apple-specific manufacturing processes and expertise.

- Quality control and assurance.

- Manufacturing planning and scheduling.

- Refurbishing functions.

Head Offices of the Irish Companies

Neither AOE nor ASI had any employees outside Ireland, they only had directors. The board of directors was based in the US, but did not have an active and/or critical role in the management of the Apple Group's IP, as evidenced by the minutes of board meetings provided by Apple. In particular, the minutes showed that the board of directors of AOE and ASI performed minor administrative functions relating to banking matters, the approvals for the distribution of dividends and the receipt and signing of financial statements and other documents. According to the minutes, the board of directors did not participate in the negotiations of the CSA. Furthermore, according to the minutes, the board of directors in the US even outsourced some functions, including full board functions, to employees located in Ireland.

The Commission also found that the board of directors of the Irish companies could not have the actual capacity to perform the functions relating to the commercialisation, exploitation and management of the Apple Group's IPs, as these could not be performed with only occasional board meetings. The Commission also found that the board of directors could not assume and manage the functions and risks assigned to it under the CSA, such as quality control and R&D. In fact, board meetings sometimes did not take place at all, and only written minutes were produced, further minimising the functional profile of the board.

Judgment under Appeal

The matter concerns the transfer pricing rulings provided by the Irish tax authorities in favour of Apple in 1991 and 2007 in relation to the method of apportioning the profits of its Irish branches. In the 1991 transfer pricing ruling, the Irish tax authorities allowed Apple to compute the net profits of the AOE branch on the basis of a conditional formula which took into account a percentage of the branch's operating costs, whereas the net profits for tax purposes for ASI were a flat rate of 12.5% of operating profits. Then, in 2007, the profit allocation method for the branches was changed to a percentage of operating costs for ASI and a percentage of operating costs plus a percentage of IP income for AOE. This was a form of TNMM, a one-sided profit allocation transfer pricing method. According to the investigation, no contemporaneous explanations or reports were drafted when Apple requested these tax rulings from the Irish tax authorities.

On 12 June 2013, the Commission opened an administrative investigation into the tax rulings, which was concluded on 30 August 2016 when the Commission published its decision classifying the Irish tax rulings as a form of state aid incompatible with the EU law. The Commission concluded that the Irish branches of the Apple companies were allocated IP profits on a non-arm's length basis because the branches performed most of the IP functions and assumed most of the risks, while being remunerated at a fraction of the price that would be charged by independent parties. This meant that Ireland was, in essence, granting state aid to the Irish branches (and the Apple Group) by providing a transfer pricing ruling that allowed the Irish branches to have a reduced tax base calculated in a manner that violated the arm's length principle, thereby conferring an undue advantage on them. In its decision, the Commission required Ireland to recover billions of euros of unpaid taxes from the Apple group.

The decision was contested in the CJEU in the joint cases of T‑778/16 and T‑892/16, where the General Court ruled in favour of Apple. It is important to discuss this judgment because the appeal judgment is based on many errors of interpretation by the General Court. The judgment was complicated by conflicting analyses undertaken by the Court.

The Irish tax provision at the centre of the discussion was Section 25 of the Taxes Consolidation Act, 1997, which provides that non-resident companies are taxable in Ireland to the extent that they have a branch or agency there and on any trading income "...arising directly or indirectly through or from the branch or agency, and any income from property or rights used by, or held by or for, the branch or agency, but this paragraph shall not include distributions received from companies resident in the State...". Apple relied on the case of S. S. Murphy (Inspector of Taxes) v. Dataproducts (Dub.) Ltd. [1988], which held that profits from property owned by a non-resident company could not be attributed to the Irish branch, even if the property was placed at the disposal of the branch, if the property was owned and controlled by non-resident directors, and the General Court concluded that the Commission had used an inappropriate "exclusive" method of profit attribution which, in the General Court's view, was inconsistent with Irish tax law. The "exclusive" method in this context meant attributing profits from the other parts of a non-resident company to the branch if the branch did not carry out the activities that generated those profits.

On the one hand, the Court sided with the Commission and agreed that the arm's length principle as developed by the OECD and the Authorised OECD Approach to attributing profits to permanent establishments could be used by the Commission as a benchmark to assess whether a transfer pricing ruling was in line with EU state aid rules. On the other hand, the General Court concluded that the Commission did not correctly apply the arm's length principle and the Authorised OECD Approach because, according to the Court, the Commission concluded that since the Irish companies did not have employees capable of managing the IP outside the branches that meant that all the IP income of the Irish companies had to be attributed to the branches, but the Commission did not prove that these branches actually performed the IP management functions.

In addition, Apple argued that the Commission erred in its functional analysis by failing to consider, as Apple claimed, that the majority of strategic decisions regarding the IP were taken by the executives and board members in the US, according to the evidence submitted by Apple.

As regards the functional analysis, the General Court mainly sided with Apple – according to the Court the Commission failed to prove that the directors of ASI and AOE did not actually manage all the functions and risks related to the IP of the Apple group on a day-to-day basis and as was mentioned in the CSA. The quality control functions were performed by many people around the world and only one person performed such a function in Ireland – according to Apple. It was also argued that the Irish branches did not perform any "real" R&D work. The Irish branches also did not develop the marketing strategies themselves and neither did they have any marketing staff. Other functions, such as customer service and data collection, according to Apple and accepted by the General Court, were support and ancillary functions which did not justify allocating the majority of the profits from the IP to the branches. As for the AOE branch, the manufacturing expertise and processes developed by that branch were limited in scope and did not justify allocating further profits from the IP to the branch. Apple also argued, and the General Court agreed, that the central decision making functions regarding the management of the IP was performed in the US by the board of directors of AOE and ASI and of Apple Inc., including key R&D and marketing decisions. Apple also presented evidence that Apple Inc. entered into Original Equipment Manufacturer ("OEM") and telecommunications operator agreements on behalf of the Irish branches, and that the ASI branch granted Apple Inc. officers power of attorney to sign contracts on behalf of and for the benefit of the branch, thus demonstrating that strategic decisions were made in the US in relation to the Apple Group's IP. It is also noteworthy that the General Court stated that the fact that the minutes of the board meetings at the US head offices did not contain any information on the taking of important and strategic decisions concerning the Apple Group's IP did not mean that these decisions were not in fact taken (in essence saying that the absence of evidence does not mean evidence of absence). In addition, according to the General Court, it was evident from the minutes that the directors of the head offices were granted wide managerial powers.

CJEU's Decision in the Appeal

The CJEU made a very thorough and detailed assessment of the General Court's analysis and found in favour of the Commission, citing procedural errors (in particular in relation to the law of evidence and misinterpretation of the facts) and misapplication of the arm's length principle and the OECD's Authorised Approach to the attribution of profits to permanent establishments.

First, the Grand Chamber overturned the General Court's conclusion that the Commission had used the "exclusion" method (which was agreed by both parties and the General Court to be contrary to Irish tax law) to conclude that profits from the IP should have been attributed to the Irish branches - the General Court had misinterpreted the Commission's reasonings. The Commission correctly based its conclusions on the observation that, firstly, the head offices did not have the necessary capacity to perform the functions of managing the Apple group's IP and, secondly, that the functional profiles of the branches were significant enough to attribute the profits of the Apple IP to those branches. The Commission did perform the functional analysis on the Irish branches and their head offices.

Second, the Commission challenged the fact that the General Court compared the functions of the Irish branches with those of Apple Inc. when the General Court should have compared the functions of the Irish branches with those of the head offices of the Irish companies. The Grand Chamber stated that as per the OECD Authorised Approach, one must look at the permanent establishment (i.e., the Irish branches in this case) and the other parts of the company, and other separate entities should not be taken into consideration. Apple attempted to challenge this on procedural grounds, but the Grand Chamber held that it has jurisdiction to review and rule on substantive inaccuracies, distortion of evidence, misrepresentation of evidence, misapplication of the burden of proof and, ultimately, to review the findings of the General Court where those findings are themselves contrary to EU law. Thus, the Grand Chamber first held that the General Court relied on inadmissible evidence by accepting Apple's claim that it was Apple Inc. that negotiated and signed contracts with OEMs and operators on behalf of the Irish branches, since the emails and the contents of the power of attorneys presented by Apple were produced after the Commission's administrative procedure had been concluded. The Grand Chamber stated that the Commission was not obliged to take into account evidence that had not been submitted to it during the administrative procedure. Moreover, the email exchanges were irrelevant in any event, as they only reported on the activities of Apple Inc. employees in the US. As regards the power of attorney agreements, although they were mentioned and listed to the Commission during the administrative procedure, their content was not, and some of them were only produced much later (or not at all), during the judicial procedure. Thus, the General Court used inadmissible evidence (and even if it were admissible, it was ineffective from a substantive point of view) to rule in Apple's favour.

Third, the General Court erred in relying on the functions of Apple Inc. and comparing them to the functions performed by the Irish branches. In fact, the General Court failed to find that the US head offices of the Irish companies were involved in the adoption of strategic decisions by Apple Inc. and were not involved in the implementation of those decisions or in the active management of the IP. The General Court thus made a crucial error in attributing to the head offices of the Irish companies in the US the essential functions performed by Apple Inc. The activities of the parent company of the non-resident Irish company should not have been taken into account.

Fourth, the General Court placed an undue burden of proof on the Commission by concluding that the fact that the minutes of the board meetings did not prove that strategic and important decisions concerning the IP were not taken did not mean that those decisions were not taken.

The Grand Chamber then ruled on the substance of the case,

holding that the Commission was correct in concluding that the

profits of the Apple group from the IP should have been attributed

mainly to the Irish branches, based on the functional analysis of

the branches in combination with the lack of consistent evidence

that the strategic decisions were taken and implemented by the head

offices in the US.

It is also interesting to note that the Grand Chamber did not

accept Apple's arguments that the Commission breached the

principles of non-retroactivity by relying on the OECD Transfer

Pricing Guidelines and the Authorised Approach, which were

published in 2010. The Court allowed the Commission to use these

documents because they provided valuable guidance on the arm's

length principle and the determination of the tax base of Irish

branches, but the Commission's main legal action was not based

on the allegation that Ireland and Apple had failed to comply with

OECD standards, but that there has been a breach of Article 107(1)

of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, which has

been part of the Irish legal system since 1973.

Conclusive Analysis and Practical Recommendations for MNE Groups

This ruling underlines the fundamental principle that transfer pricing arrangements should reflect the economic and commercial reality of the business, but it also highlights that economic and financial reality is often not self-evident and requires rigorous defence and presentation of quality evidence. Substance is critical and will become even more so as international tax law and transfer pricing evolve, and the mere presentation or creation of notional substance can be a big risk factor for an MNE group's tax structuring. When presenting evidence and transfer pricing documentation to an audit or inspection, an MNE group should not assume that alleged facts will be taken for granted or accepted at face value without further investigation and cross-examination. Case C-465/20 provides a multi-billion-euro lesson for MNE groups, which can be broken down into several practical components.

First, it highlights the critical importance of having quality and descriptive contemporaneous transfer pricing documentation and, more importantly, the timely production of such documentation. There is a plethora of transfer pricing court cases showing how MNE groups' transfer pricing policies and arrangements have succumbed to audit and investigative attacks due to either poor quality and/or lack of or inconsistent transfer pricing documentation. The OECD Transfer Pricing Guidelines state in paragraph 5.7 that contemporaneous documentation will allow the taxpayer to have integrity in its transfer pricing arrangements and add in paragraph 5.27 that the taxpayer should base them on the information reasonably available at the time of the transaction. Also, the OECD's Report on Attribution of Profits to Permanent Establishments states in paragraph 39 that taxpayers are encouraged to prepare contemporaneous documentation on internal dealings involving a permanent establishment as it can substantially reduce future controversies. As can be seen from the procedure in this case, Apple did not provide all the necessary information during the Commission's administrative procedure, which led to two problems - the fact that the late submission of additional information made it inadmissible in the court proceedings, and it also did not play in favour of Apple's image due to how the matter was handled. One can question the reasons why sufficient information was not provided at the outset of the investigation, and it would not be reasonable to conclude that perhaps some documentation was collected and attempted to be provided after the fact.

This leads to the second point. Transfer pricing documentation should be collected and produced on demand, not on an as-needed basis. Especially when dealing with large multinational groups that have oceans of internal data and are constantly in the focus of the public, the media and tax authorities, it is critical that all matters relating to internal transfer pricing arrangements, policies and documentation are organised and contained in a ready-to-present format. Prudent transfer pricing compliance does not stop at conducting a comparability study, pricing benchmarking, calculations and the overall preparation of a transfer pricing study - that is the bare minimum. It must also involve the diligent collection of all relevant data and evidence in a readily accessible format and, very importantly, the review and updating of that data and evidence on a reasonably regular basis. At least on an annual basis. Contracts should be continually updated to reflect changes in functions performed, assets used and risks assumed. All important internal communications that may affect the transfer pricing arrangement should be carefully and diligently archived and indexed so that they can be produced on request. Most importantly, any changes in economic realities must be promptly reflected in the related parties' contractual arrangements and documented in the transfer pricing documentation. A useful tool to have in the transfer pricing documentation is a changelog that reflects and describes the developments that occur in the economic and financial relationships of the parties. This will demonstrate to the tax or regulatory authorities that the MNE group has carried out a continuous transfer pricing review and will make any defence much easier.

This case also highlights the critical importance of a proactive approach to transfer pricing risk management. It is important to look at the transfer pricing documentation that an MNE group has in place and undertake a hypothetical exercise of being audited by the tax authorities. This would involve analysing the angles of attack and potential weaknesses in the group's transfer pricing arrangements. This can be done either internally or by engaging a consulting firm to conduct the audit and identify potential issues. Whenever there is transfer pricing documentation, there is always a need to analyse what questions a tax authority might ask in relation to such evidence, and what other additional information or documentation might better substantiate the MNE group's transfer pricing position. This may not be a cheap exercise, but when millions or even billions are at stake, it is a good premium to pay for a good insurance policy.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.