- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy and Metals & Mining industries

- within Tax and Consumer Protection topic(s)

IP Valuation is a specialised field, as was explained in our previous article. In summary, our IP Valuation hypothesis is rooted in sustainability, illustrated by two interdependent trend lines – cash flow and growth. There will always be market pull, based on financial viability, and a technology (or product) push, based on product feasibility. Sustainability serves as the common ground, essential for the market and technology to coexist and function effectively, failing which no value can be derived from the underlying IP.

Since the publication of the first article the author has had the opportunity to calibrate the IP Valuation hypothesis. These examples are embedded in the negotiation process between the IP rightsholder or entrepreneur and the buyer. Some intriguing observations were made with SAAS, deep tech, fintech and service-related ventures.

In many cases the IP rightsholders or entrepreneurs assume that the buyer is going to haggle their price, resulting in inflated IP values as opening offers. In return the potential buyer simply moves on or plays the long game. The only way to close a deal is by means of principled negotiations – never haggle, but negotiate. Principled negotiations in the IP world heavily draw on sustainability as the common denominator and as has been said before, a mutual understanding of the underlying IP's ability to generate growth and a positive cash flow. Essentially this implies that the IP rightsholder or entrepreneur must have some appreciation of how business works and not push the technology into the throat of a potential buyer.

The principles are, from an IP perspective, a viable business and feasible product offering, and from a buyer's perspective growth and cash flow, with sustainability as the only common ground during the opening salvos. It goes without saying that these principled negotiations draw on the work of Fisher and Fry, as well as Scotwork.

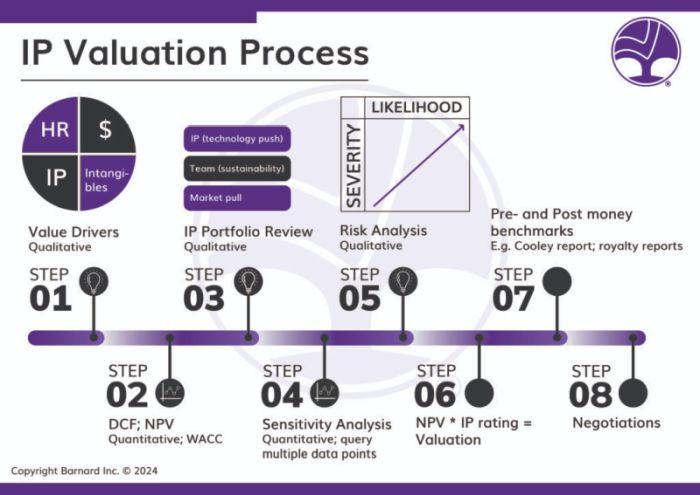

Prepare. IP rightsholders and startup entrepreneurs can assume that the buyer will default to financial statements, which are often not available because of the early-stage nature of the venture. Therefore, something else needs to be availed, which is an IP valuation which is based on qualitative and quantitative methodologies. The qualitative arrows in your quiver are crucial if the venture is early-stage and may require due diligences on some aspects, eg the novelty of a provisional patent. The preparation phase is illustrated in the flow diagram.

Argue. The better you are prepared the easier it will be to argue your case. The qualitative arguments will most likely dominate the early stages of the conversation, which should not be confused with the actual negotiations that will follow.

Signal. During the opening conversations both sides will signal preferences. For example, with a deep-tech venture, the buyer is going to be highly critical towards your ability to scale, working capital, supply chain, longer timelines due to regulatory compliance and post-sale support. The buyer's funding strategy will then be aligned accordingly. Conversely, with SAAS the buyers are going to push for quick returns.

Propose. We are now back at the beginning of this article, where it was mentioned that IP rightsholders or entrepreneurs often open negotiations with an unrealistic proposal because of uncertainty. With a quiver full of high-quality arrows (the preparation phase), some wisdom is required to make a credible, realistic and defendable opening proposal, whilst not shooting all your arrows at once. In other words, have options at your disposal, but stick to your strategic objectives. Again, for deep-tech and SAAS different proposals are required.

Package. By now the buyer should have sent signals of preferences, which give the IP rightsholders or entrepreneurs an ideal opportunity to have a fresh look at your arrows, understand why the offer was turned down, and use the opportunity to temporarily walk away until you are better positioned. For example, if you developed novel analytical methods in the healthcare diagnostic sector, the buyer is going to insist on accreditations. In other words, you failed the feasible product test, which is a qualitative requirement. Your packaging strategy may then be to agree using the money to get the appropriate accreditations, but never to lower the price.

Bargain. With start-ups this step is arguably the hardest. Your minimum viable product (mvp) may not be ready and as a result the buyer is going to force you into making concessions. Be ready for this and always make conditional concessions, meaning that when you concede, the buyer must also concede on something of value to the buyer.

Bringing this home to close the deal requires, on the one hand, the buyer to appreciate the product offering's feasibility, despite its technological readiness levels (TRL) and, on the other hand, the IP rightsholder or entrepreneur to appreciate the buyer's appreciation of growth and positive cash flow. When the negotiations are concluded in this manner, both sides have value to offer, and concessions of value are easier to appreciate.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.