- within Corporate/Commercial Law and Technology topic(s)

- in Europe

A patent confers on its owner the right to exclude others from practicing the invention claimed in the patent. In the United States, infringement becomes willful when the infringing activity is carried out deliberately and intentionally with prior knowledge of the patent (see Power Lift, Inc. v. Lang Tools, Inc., 227 U.S.P.Q. 435, 438 (Fed. Cir. 1985).

Recently, the US Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit issued a decision in an ongoing dispute between Pavo Solutions, LLC ("Pavo") and Kingston Technology Company, Inc. ("Kingston") (Pavo Solutions, LLC v. Kingston Technology Company, Inc., CAFC, June 3, 2022), which addresses the questions of a) whether a district court can amend an evident clerical error in a patent; and b) whether the district court can find that there was willful infringement after correction of the clerical error is made and as a result thereof.

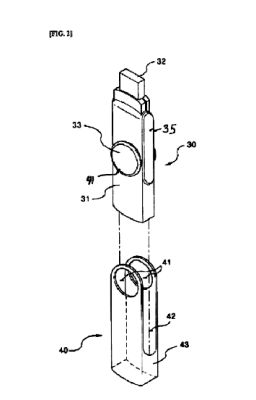

US Patent no. 6,926,544 ("the '544 Patent") was assigned to Pavo in 2015, from CATR Co. ("CATR"). The '544 patent is directed to "[a] flash memory apparatus having a single body type rotary cover." (id, 2). Fig. 2 clearly illustrates the claimed flash memory apparatus:

On August 22, 2014, CATR Co. ("CATR"), prior to assigning the '544 Patent to Pavo, sued Kingston alleging infringement of that patent. On assignment, Pavo replaced CATR as the plaintiff.

During the proceedings, the district court judicially corrected the language of claim 1 so as to read: "pivoting the cover with respect to the flash memory main body," rather than "pivoting the case with respect to the flash memory main body", in accordance with support from the patent specification (emphasis added). During trial the jury found that Kingston willfully infringed the '544 Patent and awarded damages to Pavo.

In its appeal, Kingston argued that the district court erred when it judicially corrected the claim. Furthermore, Kingston argued that it could not have willfully infringed the '544 Patent, because Kingston reasonably relied on the fact that it did not infringe the claims of the '544 Patent, as originally written i.e. before judicial correction.

In its decision, the Federal Circuit held that the district court aptly corrected an obvious minor clerical error in the claims. The court explained that correction of a clerical error in a claim is appropriate "only if (1) the correction is not subject to reasonable debate based on consideration of the claim language and the specification and (2) the prosecution history does not suggest a different interpretation of the claims." (id. 7). Furthermore, in determining a particular correction to be appropriate, the court "must consider how a potential correction would impact the scope of a claim and if the inventor is entitled to the resulting claim scope based on the written description of the patent." (id., 7-8).

In its analysis the court determined that the error in the claim was clear from the full context of the claim language and the support provided by the specification. Therefore, the judicial correction was "merely giving to it the meaning which was intended by the applicant and understood by the examiner." (id., 13). The court next determined that the prosecution history did not suggest a different interpretation of the claim, since the Applicant, the Examiner and the courts were consistent with understanding the scope of the invention recited in the claims.

Based on its conclusion that the district court acted correctly in correcting the clerical error recited in the claim, the court further determined that Kingston had willfully infringed the patent. The court explained that Kingston could not rely on "an obvious minor clerical error in the claim language" as a defense to willful infringement. (id., 16). The court explained that it based its reasoning behind this determination on the fact that "[a]n obvious minor clerical definition, does not mask the meaning" of the claim and therefore Kingston could not "hide behind the error to escape the jury's verdict". (id. 16).

A couple of takeaways come out of this decision.

First, and as mundane and 'obvious' as this sounds, mindfulness and proofreading are essential skills for patent attorneys. Ensuring that a claim actually recites what is intended is essential to ensure that the client receives the patent that he thought he was paying for. Kingston was unfortunate that despite the claim error being relatively minor, so as to be entered by the court, it constituted enough of a change so as to work against them. However, other court decisions emphasize the implications of what can occur when a clerical error results in an opposite outcome in which there is no infringement (see for example, CBT Flint Partners, LLC v. Return Path, Inc.)

Second, an infringement analysis should take into consideration the claim language and any possible clerical errors, especially to avoid the risk of a claim of willful infringement. Erring on the side of caution in this matter can be the difference between no infringement, infringement and willful infringement. In the current situation, had Kingston sought an infringement opinion from a patent attorney that erred on the side of caution and did not rely on a clerical error in the claims, Kingston may have not been liable for willful infringement or perhaps may have avoided infringement action altogether.

In conclusion, this case emphasizes the fact that a patent attorney and his clients live and die by the pen and the reliance on the recited scope of the claims of a patent. Therefore, as patent attorneys there is a fiduciary duty to ensure that a claim actually recites the intended scope to ensure a high-quality work product when drafting a patent application. Additionally, a patent attorney should err on the side of caution when providing a client with guidance in a potential infringement situation and avoid relying on errors in a patent when assuring the client that they are not infringing the patent.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.