- within Criminal Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Banking & Credit and Law Firm industries

- within Criminal Law topic(s)

- with readers working within the Law Firm industries

- within Strategy, Privacy, Media, Telecoms, IT and Entertainment topic(s)

In the realm of commercial transactions, the concepts of fraud, gross negligence and wilful misconduct serve as crucial markers for assessment of risk and determination of liability. These concepts are pivotal in shaping negotiations on liability provisions (including those related to indemnity) for building in exclusions to limitations of liability for events arising out of fraud, gross negligence, and wilful misconduct. While these terms are frequently used, their precise scope and interpretation remains a debatable topic during contract negotiations.

This article aims to present an overview of these terms as interpreted in the Indian legal context under the statutes and by the courts and provide an insight into their usage and practical considerations in M&A and fund-raising transactions.

1. Fraud

1.1. Concept and Judicial Analysis

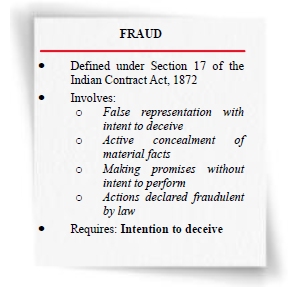

- Meaning: Fraud is defined under Section 17 of

the Indian Contract Act, 1872 ("Contract

Act"), as an act committed by a party with the

'intention to deceive' the other party, or to induce such

party to enter into a contract, which includes, inter

alia: (i) suggesting a fact as true which the suggesting party

knows to be untrue; (ii) actively concealing a fact despite having

knowledge of such fact; (iii) promising anything without having any

intention of performing it; (iv) committing any act with the

intention to deceive the other party; and (v) committing any act

which has been declared as fraudulent by law.

A mere false representation is not fraud unless coupled with an intention to deceive.1 In cases of fraud, the person making the statement knows it to be false, whereas in misrepresentation, such person genuinely believes the statement to be true. In both instances, the falsity of the statement misleads the other party.2 However, in both cases, the misrepresented statement must be material enough to induce a reasonable person to enter into the contract.3 While fraud can give rise to both criminal and civil liability, this article focuses only on events of fraud leading to civil liability. - Duty to disclose: Section 17 of the Contract Act clarifies that, while interpreting fraud, it is presumed that there is no duty on any party to voluntarily disclose all facts that may influence the willingness of the other party to enter into a contract. This aligns with the principle of caveat emptor (i.e., buyer beware) which binds a buyer with the actual as well as constructive knowledge of any fact which may influence the buyer's decision to enter into an agreement, if such fact is obvious and might have been known by ordinary diligence by the buyer.4 However, where the circumstances necessitate a duty to speak, or where silence would be equivalent to speech, such silence would qualify as fraud.5

- Fraud in the Making v. Performance of

Contracts: The consequences of fraud vary depending on the

stage of occurrence of the fraudulent act or omission:

- At the time of making of a contract: Under Section 17 of the Contract Act, the effect of fraud has been covered to the extent that the consent to a contract is procured by it.6 In such cases, the contract becomes voidable at the instance of the aggrieved party, and such party has the option to affirm the contract, or insist that the contract be rescinded or the party be restored to its pre-contractual position.7

- At the time of performance of a contract: Where there is fraud in the performance of the contract, apart from its making, then it cannot be voided at the instance of the aggrieved party, i.e., such non-performance does not constitute grounds for rescission or for restoring the parties to their pre-contractual position.8 The court may, however, award damages or grant the equitable relief of specific performance, as it may deem fit.9

- Fraud in Public Law v. Private Law: Fraud in

'public law' is not the same as fraud in 'private

law'.10 For clarity, public law governs the

relationship between a person (individual or an entity) and the

state/government, whereas, private law governs the relationship

between persons in relation to a contract. Thus, fraud, in relation

to the public law would occur when there is a colourable

transaction to evade the obligations under an applicable

law.11

However, in all the above instances, the courts have consistently interpreted that the common ingredient of fraud is an 'intention to deceive', even if the deception results in: a non-economic advantage to the deceiver, or a non-economic loss to the deceived.12

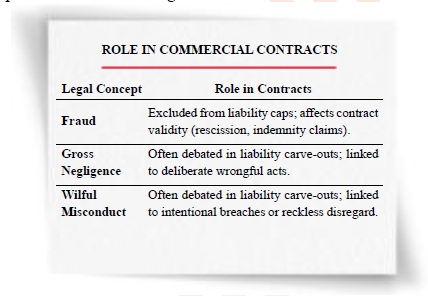

1.2. Role in Commercial Transactions

- Representations and Warranties: Representations and warranties ("R&Ws"), including those backed by indemnities, often find their way in contracts to induce the parties to enter into commercial arrangements. In alignment with the principle of caveat emptor, a due diligence exercise is also carried out obligating the warrantors to disclose all the relevant facts prior to such transactions. A representation is also sought that all the facts and information disclosed by the warrantors, necessary for the other parties to enter into the contract, have been disclosed. An active concealment of any fact thereupon could be considered as 'fraud', enabling the other parties to make a claim (including an indemnity claim) against the warrantors.

- Exclusion from Limitations to Liability: While parties generally negotiate various limitations on the warrantors' liability against such R&Ws, including inter alia, time limits, monetary cap, de-minimus and basket thresholds, etc., 'fraud' is typically excluded from these liability caps.

- Termination and Materiality: Generally, if there is any inaccuracy in any R&W which is not material to the contract, fraud as a ground to terminate the contract remains untenable.13 To secure this right, a provision is added allowing termination of the contract if any R&W turns out to be untrue, regardless of its materiality. However, if there is any inaccuracy in any material R&W (especially in relation to the authority and title related R&Ws), termination or rescission of the said contract can be sought.

2. Gross Negligence

2.1. Concept and Judicial Analysis

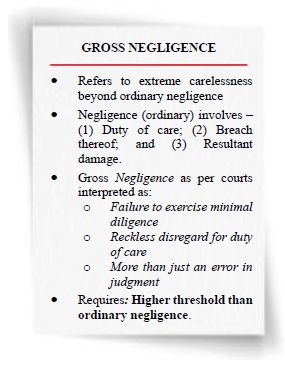

- Meaning: The term 'gross negligence' refers to the failure to exercise even a basic level of care that a reasonably prudent person would undertake in similar circumstances.14 It represents a higher threshold of negligence and is often equated with recklessness. While, the term 'gross negligence' has not been explicitly defined in Indian statutes, the concept of 'negligence' arises from the idea of 'duty of care' owed by one person to another.15 The courts in India have considered the definition of gross negligence as provided under various legal dictionaries which define the said term as: "a lack of even slight diligence or care. The difference between gross negligence and ordinary negligence is of degree and not of quality. Gross negligence is traditionally said to be the omission of even such diligence as habitually careless and inattentive people do actually exercise in avoiding danger to their own person or property."16

- Duty of Care and Degree of Negligence: The

essential components of negligence are threefold: (i) duty of care;

(ii) breach of such duty; and (iii) resultant damage.17

Further, it is well settled that a 'duty of care' subsists

between the parties negotiating a contract, if the information is

given by a party in connection to the contract, especially when the

person giving the information had special knowledge or skill in

relation to it.18

However, when it comes to the determination of occurrence of gross negligence and (ordinary) negligence upon breach of such 'duty of care', the legal standards have been determined by the Indian courts on a case-to-case basis:

- In the case of In Re: Seacoast Shipping Services Limited and Ors. (2024), the Securities and Exchange Board of India (SEBI) had treated acts of misrepresentation of financials, fraudulent preferential allotments and diversion of funds by managing director and promoters, which misled the investors into subscribing to the shares of the company, as gross negligence.19

- In the case of ICAI v. Mukesh Gang (2016), the High Court of Hyderabad held that a false certification issued by a chartered accountant acknowledging receipt of money before verifying the same from accounts would amount to 'gross negligence'.20

- In the case of T.A Kathiru Kunju v. Jacob Mathai (2017), the Supreme Court held that mere negligence or error of judgment on behalf of an advocate, would not be considered as gross negligence. It was held that gross negligence requires "an element of moral turpitude or ethical breach beyond simple errors in judgement."21

Thus, while the components of negligence (i.e., duty of care, breach thereof, and resulting damage) are well-defined, the determination of gross negligence versus (ordinary) negligence is subject to case-specific legal standards, as demonstrated by Indian courts in various contexts.

2.2. Role in Commercial Contracts

Distinguishing between ordinary negligence and gross negligence becomes crucial while determining indemnity obligations in M&A, PE, and VC transactions. Acts of gross negligence are often excluded from any liability caps, while acts of (ordinary) negligence may or may not remain subject to such limitations. This distinction ensures that more severe lapses in duty, such as reckless or intentional disregard of risks, are not shielded by caps on liability, providing greater protection in such events. However, these carve-outs are often debated and resisted due to the uncertainty surrounding what may be considered "gross negligence" in a specific context.

3. Wilful Misconduct

3.1. Concept and Judicial Analysis

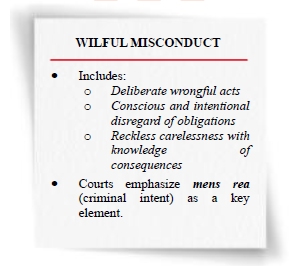

- Meaning: The courts in India have placed

reliance on definition of wilful misconduct as provided in various

legal dictionaries, which define the said term as "failure

to exercise ordinary care to prevent injury to a person who is

actually known to be or reasonably expected to be within the range

of a dangerous act being done"22 and

"misconduct to which the will is a party, it is something

opposed to accidental or negligent; the 'mis' part of it,

not the conduct, must be wilful".23

In this regard, wilful misconduct can be said to include, inter alia:24

- deliberately and wilfully committing a wrongful act or omission;

- consciously and intentionally disregarding legal or contractual obligations;

- acting with the knowledge of an act's wrongful nature; and

- exhibiting reckless carelessness, with disregard for the consequences.

- Intent separates Inadvertent Errors from Wilful Misconduct: In the case of Ace Manufacturing Systems Ltd. v. State of U.P. & Ors. (2024), the Allahabad High Court observed that wilful misconduct requires an element of mens rea (criminal intent) for imposition of penalties, in tax-related matters. It was held that penalties cannot be imposed based on mere assumptions or conjectures, rather there must be substantive evidence demonstrating wilful intent to evade tax. Further, it was observed that mens rea serves dual critical purposes: (i) preserving the integrity of legal system by distinguishing between inadvertent errors and intentional misconduct; and (ii) acting as a deterrent to deliberate non-compliance by prescribing severe consequences.

3.2. Role in Commercial Contracts

Generally, the acts of wilful misconduct are kept outside any liability caps in an agreement, while acts of (ordinary) misconduct may or may not be subject to such limitations. This distinction ensures that intentional misconduct, including reckless disregard of obligations, are not shielded by any caps on the liability, providing reasonable protection in such events.

Similarly, just as wilful misconduct is sought to not be subject to any limitation on liability caps, knowledge qualifiers are often added in R&Ws to limit liabilities to intentional or known breaches. This ensures that liability arises only from deliberate misconduct or conscious disregard rather than inadvertent errors beyond a party's knowledge, such as unknown breaches of contract terms or of R&Ws, such as unintentional breach of third-party intellectual property rights. Both "wilful" and "knowledge" qualifiers serve to distinguish intentional misconduct from mere negligence or oversight, ensuring that liability is imposed only where there is conscious wrongdoing.

4. Concluding Remarks

Fraud, wilful misconduct, and gross negligence are often seen as major unknown risks in M&A, PE and VC transactions. To mitigate these risks, comprehensive protections against such events are often sought without any limitations on liability, and the liabilities upon the occurrence of these events are often negotiated to even extend to the personal assets of the indemnifying party, and beyond the contract value.

However, proving fraud, wilful misconduct and gross negligence is easier said than done. Fraud and wilful misconduct require establishing mens rea and meeting a high burden of proof, while gross negligence is often interpreted as reckless disregard. Due to these difficulties, parties generally seek to broaden the scope of these acts in transaction documents, ensuring stronger protections.

On the other hand, there is also increasing caution around including acts of fraud, wilful misconduct, and gross negligence as indemnification events, given the unpredictability of their liability, which is dependent on case-by-case interpretations. Some may also argue that additional indemnification provisions for these acts may be redundant, as legal remedies already exist and would naturally be pursued in such events.

Footnotes

1. Kamal Kant Paliwal v. Smt. Prakash Devi Paliwal and Ors, AIR 1976 Raj 79.

2. Niaz Ahmed Khan v. Parsottam Chandra, AIR 1931 All 154: 53 All 374.

3. Bhagwani Bai v. LIC of India, AIR 1984 MP 126.

4. Commissioner of Customs v. M/S Aafloat Textiles (I) Pvt. Ltd., AIR 2009 SC (SUPP) 2320.

5. The duty to disclose varies basis the relationship between the parties to a contract. For contracts of insurance and those involving fiducial relationships, there is a special duty to disclose all facts, regardless of disclosure requirements. However, in ordinary commercial contracts, there is generally no obligation to disclose, as each party is expected to gather necessary information independently. (also see Banque Financiere de la Cite SA v. Westgate Insurance Co. Ltd., [1989] 2 All ER 952 at 1010, [1990] 2 All ER 947]).

6. Pollock, F., Mulla, D. F., & Yashod Vardhan, R. (2022), The Indian Contract & Specific Relief Acts, LexisNexis.

7. Jamsetji Nassarwanji v. Hirjibai Naoroji, (1913) 37 Bom 158.

8. Jamsetji Nassar-wanji v. Hirjibhai Naoroji, (1912) I.L.R. 37 Bom, 158; 15 Bom, L.R. 192; Avitel Post Studioz Limited and Ors. v. HSBC PI Holding (Mauritius) Limited, AIR Online 2020 SC 691; Fazal D. Allana v. Mangaldas v. M. Pakvasa, AIR 1922 Bom 303.

9. Bal Krishna & Anr v. Bhagwan Das (Dead) & Ors, 2008 AIR SCW 2467.

10. Commissioner of Customs, Kandla v. M/S Essar Oil Limited & Ors., AIR ONLINE 2004 SC 931.

11. Bhaurao Dagdu Paralkar v. State of Maharashtra & Ors, 2005 (7) SCC 605.

12. Vimla (Dr) v. Delhi Admn., 1962 SCC OnLine SC 172.

13. Bhagwani Bai v. Life Insurance Corporation of India, AIR 1984 MP 126.

14. State of U.P. v. McDowell & Co. Ltd., (2022) 6 SCC 223.

15. Union of India & Ors. v. Suguali Sugar Works (P) Ltd., (1976) 3 Supreme Court Cases 32.

16. Black's Law Dictionary, 10th Edition.

17. State of Punjab v. Shiv Ram & Ors., AIR 2005 Supreme Court 3280.

18. Esso Petroleum Co Ltd. v. Mardon, [1975] QB 819, as cited in Vestas Wind Technology India Private Limited and Ors. v. Inox Renewables Limited and Ors., AIR 2019 (NOC) 710 (BOM).

19. In Re: Seacoast Shipping Services Limited and Ors., MANU/SB/3495/2024.

20. ICAI v. Mukesh Gang (2016) SCC OnLine Hyd 327.

21. T.A Kathiru Kunju v. Jacob Mathai (2017) 5 SCC 755.

22. Black's Law Dictionary, 4th Edition; Indian Airlines v. Kurian Abraham, 2010 SCC OnLine Ker 461.

23. Stroud's Judicial Dictionary of Words and Phrases, Volume 3.

24. Bengal Nagpur Railway Co. v. Moolji Sikka & Co., 1930 SCC OnLine Cal 176; Ace Manufacturing Systems Ltd. v. State of U.P. & Ors., 2024 SCC OnLine All 4924; Bengal Nagpur Railway Co. Ltd. v. Dhanjishah Pestonji, 1929 SCC OnLine Cal 126; Syad Akbar v. State of Karnataka, (1980) 1 SCC 30.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]