Michael Caine, a Principal of Davies Collison Cave Pty Ltd, has spent many years studying various aspects of Article 4 of the Paris Convention, either as convenor of the International Patents Committee of the Institute of Patent and Trade Mark Attorneys of Australia (IPTA), or in carrying out roles he has held within the (International Patents) Study & Work Commission (CET) of the International Federation of Intellectual Property Attorneys (FICPI), where he currently serves as Vice President of the CET. Michael's paper on Article 4C(4) of the Paris Convention entitled "When is it safe to refile or update a priority application?" and a report of a study he carried out within FICPI in relation to Article 4A(1) entitled "Guidelines for Transferring Priority Rights" have been widely consulted.

Closely related to the topic of this paper and Articles 4F and 4G of the Paris Convention is a paper Michael published in 2014 entitled "Poisonous priority arrives in Australia and New Zealand". In that paper, Michael explained how the Full Federal Court of Australia in AstraZeneca AB v Apotex [2014] FCAFC 199 interpreted a provision of the Patents Act 1990 (Cth) in a manner that failed to recognise multiple and partial priority in a single claim, except in circumstances where the claim is expressed as alternatives, giving rise to the possibility of poisonous priority and poisonous divisionals. He also explained how the absence of a provision in New Zealand Patent law to allow a single claim to be entitled to more than one priority date gives rise to poisonous priority and poisonous divisionals.

Michael has now carried out and reported on a study with his FICPI CET colleague, Harrie Marsman from VO Patents & Trademarks in The Netherlands, to ascertain whether there are other countries that do not fully recognise multiple and partial priorities within a single claim and, if so, whether that can give rise to poisonous priority or poisonous divisionals. The study was prompted by the circumstances leading to the 2016 decision of the Enlarged Board of Appeal of the European Patent Office in case G1/15. Prior to that decision, claims in European patents or patent applications that relied on multiple or partial priorities were vulnerable to anticipation by their European priority applications or by their divisional or parent European applications.

Interestingly, of the 35 countries surveyed in the study, most fully recognised multiple and partial priorities within a single claim. The six countries identified as not providing full recognition of multiple and partial priorities in a single claim are Australia, New Zealand, Canada, China, India and the United States. Of these countries, Australia, New Zealand and China have the possibility of poisonous priority and poisonous divisionals.

WHY RECOGNITION OF MULTIPLE AND PARTIAL PRIORITIES IN A SINGLE CLAIM IS IMPORTANT

Before commenting on the scenarios set out in the questionnaire prepared by FICPI for its study of multiple and partial priorities, it is worth noting what Article 4B of the Paris Convention says about the consequences of filing an application for a patent in a country of the Union and claiming a right of priority within the fixed 12 month period in another country of the Union:

Consequently, any subsequent filing in any of the other countries of the Union before the expiration of the periods referred to above shall not be invalidated by reason of any acts accomplished in the interval, in particular, another filing, the publication or exploitation of the invention, (.) and such acts cannot give rise to any third-party right or any right of personal possession.

It is also worth noting that Article 4F of the Paris Convention specifically allows an application to claim multiple or partial priorities:

No country of the Union may

refuse a priority or a patent application on the ground that the

applicant claims multiple priorities, even if they originate in

different countries, or on the ground that an application claiming

one or more priorities contains one or more elements that were not

included in the application or applications whose priority is

claimed, provided that, in both cases, there is unity of invention

within the meaning of the law of the country.

With respect to the elements not included in the application or

applications whose priority is claimed, the filing of the

subsequent application shall give rise to a right of priority under

ordinary conditions.

While Article 4F refers to the claiming of multiple and partial priorities, there is nothing in the Article to preclude a single patent claim from being entitled to multiple or partial priorities where that claim is directed to elements (or matter) first disclosed in more than one application whose priority is claimed, and/or first disclosed in the application claiming those priorities, provided that there is unity of invention.

Scenario 1: Partial priority (alternatives)

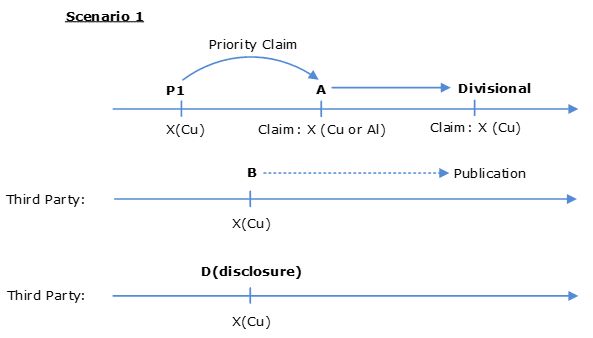

Scenario 1 set out in the FICPI questionnaire exemplifies partial priority where a new alternative is added to the PCT or foreign application relative to the disclosure of the application from which it claims priority. Scenario 1 can be summarised as follows:

- a priority setting application (P1) is filed disclosing widget X with component Y composed of copper; and

- Application A (which could be a PCT application) is filed claiming priority from P1 and having a claim to widget X with component Y composed of copper OR aluminium (Claim A).

The questionnaire then asked whether either or both of the following activities carried out independently by a third party after the filing date of P1, but before the filing date of Application A, would invalidate Claim A.

Activity 1: Filing a patent application (Application B) in (or with effect in) the country concerned disclosing and claiming widget X with component Y composed of copper, and where Application B is published after the filing date of Application A.

Activity 2: Publishing a document (Document D) disclosing widget X with component Y composed of copper.

The questionnaire also asked whether the filing of a divisional application from Application A could destroy the novelty of Claim A.

Scenario 1 can be illustrated as follows:

Third party activities

In view of Articles 4B and 4F of the Paris Convention, one would not expect either of the activities of the third party described in Scenario 1 to invalidate Claim A. However, that is exactly what can happen in certain countries if multiple and partial priorities are not recognised within a single claim.

Multiple and partial priorities are recognised for claims directed to simple alternatives in Australia, Canada and China. However, there is no recognition at all for multiple and partial priorities in a single claim in New Zealand, India and the United States. Thus, in each of New Zealand, India and the United States, Claim A would not be entitled to claim priority from P1, and the "priority date" or "effective filing date" of Claim A would be the date of filing Application A. As that is after the filing date of third party Application B, and after publication of third party Document D, both third party activities would destroy the novelty of Claim A in New Zealand and the United States. In India, Document D would destroy the novelty of Claim A and Application B would lead to prior claiming.

Divisional application

The next question to consider is whether the filing of a divisional of Application A, (the divisional application having the same disclosure as Application A) would create a co-pending application that would invalidate Claim A. Such a divisional application would contain a disclosure of widget X with component Y composed of copper, which if it were to be the subject of a claim, that claim would be entitled to the priority date of P1.

As multiple and partial priorities are recognised for claims directed to simple alternatives in Australia, Canada and China, the divisional application would not invalidate Claim A. Claim A would also not be invalidated in the United States by the filing of a divisional in view of the protection against self-collision provided under 35 U.S.C § 102. Similarly, in India a divisional can only be filed where there is lack of unity of invention, and since the relevant test is a prior claiming test, it is very unlikely that a divisional could be filed with a valid claim that could give rise to prior claiming.

However, as the priority date of Claim A in New Zealand would be the date of filing Application A, where widget X with component Y composed of aluminium was first disclosed, the filing of the divisional application in New Zealand would create an application that would be citable as a whole of contents novelty reference. Since a claim cannot be partially valid, the Claim A, which encompasses widget X with component Y composed of copper, would be regarded as lacking novelty in New Zealand. A divisional of that type is sometimes referred to as a "poisonous divisional". However, it should also be understood that the validity of a claim in a divisional that relies on multiple or partial priority can also be destroyed by its parent application/patent in New Zealand.

How can the consequences of the third party activities, or the filing of the divisional, be avoided for Scenario 1?

Although there is nothing in Article 4 of the Paris Convention to require subject matter derived from different priority sources to be placed in separate claims, it is necessary to do so in New Zealand, India and the United States in order to obtain full benefit of the claim to partial (or multiple) priority.

If Claim A were split in two, one claim directed to widget X with component Y composed of copper and another claim directed to widget X with component Y composed of aluminium, there would be no lack of novelty or prior claiming. That is because the claim to widget X with component Y composed of copper would be entitled to the priority date of P1 (which pre-dates both the filing of Application B and the publication of Document D) and widget X with component Y composed of aluminium was not disclosed in Application B or Document D.

However, since Document D was published before the priority date and effective filing date of the claim to widget X with component Y composed of aluminium, it would be citable against that claim for inventive step. Application B would also be citable against the claim to widget X with component Y composed of aluminium in the United States as it would represent so-called "secret prior art".

Scenario 2: Multiple priorities (broadening)

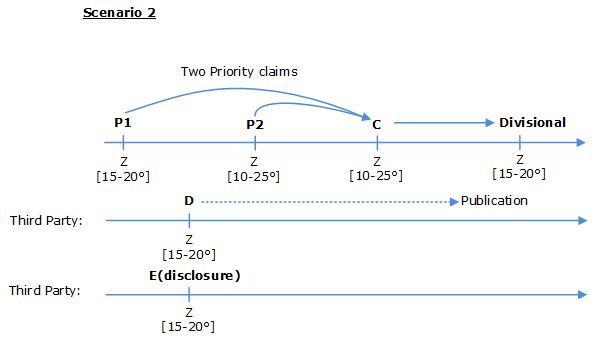

The situation becomes more complicated where, instead of adding a new alternative, a range is expanded in a later priority application relative to an earlier priority application. Scenario 2 in the FICPI questionnaire exemplifies multiple priorities where a temperature range is expanded in a subsequent priority setting application relative to that disclosed in a first priority setting application, and a PCT or foreign application is filed claiming priority from both applications. Scenario 2 can be summarised as follows:

- a first priority setting application (P1) is filed disclosing process Z carried out within a temperature range of 15-20°C; and

- a subsequent priority setting application (P2) is filed disclosing process Z carried out within a broader temperature range of 10-25°C.

- Application C (which could be a PCT application) is filed claiming priority from P1 and P2 and having a claim to process Z carried out within the broader temperature range of 10-25°C (Claim C).

The questionnaire then asked whether either or both of the following activities carried out independently by a third party after the filing date of P1, but before the filing date of P2, would invalidate Claim C.

Activity 1: Filing a patent application (Application D) in (or with effect in) the country concerned disclosing and claiming process Z carried out within a temperature range of 15-20°C, and where Application D is published after the filing date of Application C.

Activity 2: Publishing a document (Document E) disclosing process Z carried out within a temperature range of 15-20°C.

The questionnaire also asked whether the filing of a divisional application from Application C could destroy the novelty of Claim C.

Scenario 2 can be illustrated as follows:

Third party activities

As for Scenario 1, in view of Articles 4B and 4F of the Paris Convention it would be surprising if either of the activities of the third party described in Scenario 2 would invalidate claim C. However, that is exactly what can happen if multiple and partial priorities are not recognised within a single claim.

Multiple and partial priorities are not recognised for claims directed to expanded ranges in Australia, New Zealand, China, India, Canada or the United States. In each of these countries Claim C directed to the expanded temperature range would not be entitled to claim priority from P1 and, as such, the "priority date" or "effective filing date" of Claim C would be the date of filing P2. As that is after the filing date of third party Application D, and after publication of third party Document E, both third party activities would destroy the novelty of Claim C in Australia, New Zealand, China, Canada or the United States. In India, Document D would destroy the novelty of Claim C and Application B would lead to prior claiming.

Divisional application

The next question to consider is whether the filing of a divisional of Application C (the divisional application having the same disclosure as Application C) would create a co-pending application that would invalidate Claim C. Such a divisional application would contain a disclosure of process Z carried out within a temperature range of 15-20°C, which if it were to be the subject of a claim, that claim would be entitled to the priority date of P1.

As for Scenario 1, Claim C would not be invalidated in the United States or Canada by the filing of a divisional in view of the protection provided against self-collision. Similarly, in India a divisional can only be filed where there is lack of unity of invention, and since the test is a prior claiming test, it is very unlikely that a divisional could be filed with a valid claim that could give rise to prior claiming.

However, as the priority date of Claim C in Australia, New Zealand and China would be the date of filing P2, the filing of a divisional application in those countries would create an application that is citable as a whole of contents novelty reference, thereby invalidating Claim C. This is because the divisional application will contain a disclosure of process Z carried out within a temperature range of 15-20°C, which if it were to be the subject of a claim, that claim would be entitled to the priority date of P1. As for Scenario 1, the divisional in that case can be termed a "poisonous divisional".

How can the consequences of the third party activities, or the filing of the divisional, be avoided for Scenario 2?

As for Scenario 1, the solution is to place subject matter derived from P1 and P2 into separate claims. However, it is often not as straightforward to split claims directed to ranges into separate claims as it is for claims directed to alternatives. For Scenario 2, the applicant could consider splitting the claims into three claims as follows:

- Process Z carried out within a temperature range of 15-20°C.

- Process Z carried out within a temperature range of 10 to <15°C.

- Process Z carried out within a temperature range of >20 to 25°C.

Of course, support or basis for these sub ranges would likely need to be identified in the specification in order to present such claims. If allowed, proposed claim 1 would be entitled to the priority date of P1 and proposed claims 2 and 3 would be entitled to the priority date of P2. Accordingly, there would be no lack of novelty or prior claiming.

However, as with Scenario 1, the publication of Document E would be citable for inventive step against proposed claims 2 and 3. Application C would also be citable in the United States against proposed claims 2 and 3 above, as it would represent "secret prior art".

In Australia, Canada and China, where alternatives within a single claim can have different priority dates, it may be possible to present a single claim to alternatives as follows:

- Process Z carried out within a temperature range of 10 to <15°C OR 15-20°C OR >20 to 25°C.

However, in that case both Application D and Document E would be citable for inventive step against proposed claim 1 because they were published prior to the priority date and effective filing date of two of the alternative ranges.

While the invalidity issues caused by the failure of the laws in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, China, India and the United States to fully recognise multiple and partial priorities within a single claim could potentially be remedied by splitting the claims as proposed above, that may not be possible if the applicant only became aware of the third party activities after the patents have been allowed or granted, for example during an opposition or revocation/invalidity proceeding. At that point in time it would be helpful for the applicant to be able to split the claims in order to rely on the multiple or partial priority claim for which they should be entitled under Article 4F of the Paris Convention. Similarly, the self-collision consequences of filing one or more divisional applications may not be recognised until it is too late to split the claims. The situation for applicants would be far more satisfactory if multiple and partial priorities were recognised in single claims.

WHICH APPLICATION IS REGARDED AS THE "FIRST"?

Another problem caused by the failure to recognise multiple or partial priority within a single claim relates to identification of the "first" application for the purposes of calculating the 12 month priority period. For Australia, New Zealand, Canada, China, India and United States in the scenarios discussed above, the identification of the "first" application is likely to depend on whether or not subject matter derived from different priority applications is split into separate claims. If multiple or partial priority is not recognised in the single claim and the subject matter is not split, P1 is not a relevant priority application for either Scenario 1 or 2. However, if the subject matter is split into separate claims, P1 becomes the "first" application from which the 12 month priority period commences.

POISONOUS PRIORITY

Although the only self-collision scenarios considered in the FICPI study relate to the filing of divisional applications, the failure to recognise multiple and partial priorities in a single claim also has the potential to cause conflict in other scenarios. For example, self-collision can also occur between two or more applications filed in the same country at the same time claiming priority from the same priority setting application. Self-collision can also occur in the case of internal priority, where the priority setting application and the priority claiming application are filed in the same country. Conflict in these circumstances can also be termed "poisonous priority".

Such poisonous priority situations cannot arise in Canada or the United States in view of the protection against self collision, but could arise in Australia, New Zealand, China and India. In fact, poisonous priority has been recognised by the courts in both Australia and China.

ASTRAZENECA AB V APOTEX PTY LTD (12 AUGUST 2014)

In AstraZeneca AB v Apotex Pty Ltd [2014] FCAFC 99, the Full Federal Court of Australia considered whether there was conflict between two Australian patents (derived from two separate PCT applications) that claimed priority from the same UK patent application. The UK patent application disclosed a formulation of the cholesterol lowering agent, rosuvastatin, containing a tribasic phosphate salt in which the cation is multivalent, and a coating of titanium dioxide and ferric oxide.

The claims of the particular patent being considered by the Court referred more broadly to the presence of "an inorganic salt in which the cation is multivalent", and included a proviso to exclude inorganic salts where the counter anion is a phosphate. When considered most favourably, the Court believed the claim could only be considered to have a priority date corresponding to the date of filing of the corresponding PCT application, even though the claim encompassed embodiments of the invention disclosed in the earlier filed UK patent application.

The other patent, which was cited as a whole of contents novelty reference, contained claims corresponding to the disclosure of the UK patent application, specifying the presence of a tribasic phosphate salt in which the cation is multivalent. The claims of that patent, including any notional claims drawn to compositions disclosed in the examples that contained the coating of titanium dioxide and ferric oxide, were considered to have a priority date corresponding to the earlier filing date of the UK patent application. Unfortunately for AstraZeneca, the proviso to exclude inorganic salts where the counter anion is a phosphate did not provide the claim with novelty, since titanium dioxide and ferric oxide were both considered to be examples of inorganic salts in which the cation is multivalent, and in which the counter anion was not a phosphate. While oxides would not normally be considered salts, they were described as such in the specification.

Although not drawn to the attention of the Court, there was another patent application that could equally have been cited as a whole of contents reference, being a divisional of the patent under consideration by the Court. While the disclosure of the divisional was effectively the same as the disclosure in the parent patent, the claims in the divisional application were directed to ferric oxide in the coating.

Following a partially successful pre-grant opposition, claim 1 of the divisional was amended to specify that the active agent was in admixture with the inorganic salt in which the cation was multivalent. As the Court had indicated in its decision on the parent patent that a claim could be entitled to the benefit of multiple or partial priorities if drafted to specify alternatives, the claim was also drafted to specify alternatives in order to avoid a whole of contents novelty conflict with the parent patent (or the other patent filed on the same day and claiming the same priority). Accordingly, rather than specifying that the composition contained the active agent in admixture with "an inorganic salt in which the cation is multivalent", the claim was amended to specify that the composition contained the active agent in admixture with "a tribasic phosphate salt or another inorganic salt in which the cation is multivalent" [underlining added]. The first alternative would be entitled to the priority date of the UK patent application while the second alternative would be entitled to the filing date of the PCT application. Specifying that the inorganic salt was in admixture with the active agent also removed the problem of the ferric oxide present in the coating being construed as a relevant inorganic salt.

ZHAO ZHUOYAN V CNIPA (31 DECEMBER 2019)

In accordance with information provided to FICPI by Mr Chuanhong Long of CCPIT Patent and Trademark Law Office, the Supreme People's Court of China held that a Chinese patent can be anticipated by its own priority application if that priority application is also a Chinese application.

In the case considered by the Court, the applicant, Zhao Zhuoyan, filed a first application in China disclosing and claiming a method for isolating potassium oxide from potassium-containing sodium aluminate solution. One of the claims specified a concentration range of "180g/l-280g/l" and another claim specified stirring for "120-210 minutes". The first application was published a few months after it was filed. The applicant later filed a second application claiming internal priority to the first application, but in that application expanded the concentration range to "170g/l-280g/l" and the stirring time to "100-210 minutes". In view of the expanded ranges, the China National Intellectual Property Administration (CNIPA) took the view that the claims in the second application were not entitled to claim partial priority from the first application, with the result that the claims in the subsequent application were anticipated by the publication of the first application. The applicant's appeals to the Beijing IP Court, Beijing High People's Court and to the Supreme People's Court were all unsuccessful.

CONCLUSION

In order to obtain full value from multiple and partial priority claims under the Paris Convention, it is important for priority to attach to subject matter or "elements" of a claim, rather than to the claim per se. Once priority is attached to a claim, as it is in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, India and the United States, a mechanism is required to allow the elements encompassed by the claim to be entitled to a priority date corresponding to when those elements were first disclosed. That should not, in the author's view, require claim splitting.

Recognition of multiple and partial priority in a single claim is achieved in Europe by specifying the following in Article 88 EPC, second sentence:

Where appropriate, multiple priorities may be claimed for any one claim.

Australia and Canada have similar provisions, but the Courts in those countries have interpreted them in such a way that they only apply when a claim is directed to alternatives. While the priority provisions in China do not attach priority to a claim per se, the Chinese courts have interpreted priority entitlement in a restrictive manner, such that multiple and partial priority in a single claim is only recognised when the claim is directed to simple alternatives.

As proposed in FICPI's report, it would be helpful for applicants and patentees if the laws relating to the recognition of multiple and partial priorities in Australia, New Zealand, Canada, China, India and the United States were to be amended to provide full recognition of multiple and partial priorities in a single claim. Otherwise, applicants will need to be very careful in these jurisdictions and consider claim splitting in order to gain full advantage of multiple and partial priorities. Until such laws are amended, applicants and patentees in these jurisdictions should be provided with an opportunity by patent offices and/or courts to split claims after acceptance or grant, including during opposition or a revocation/invalidation action, to restore the priority to which they should be entitled under the Paris Convention.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.