Originally published in Landslide Volume 4, Number 3, January/February 2012. © 2012 by the American Bar Association.

"Design patents often are difficult to enforce. Utility patents undergo extensive examination and, once granted, have only a limited term. Any chance we can use trademark law to protect unique product designs and packaging?"

"Glad you asked."

Increasingly, companies are using trademark law in an effort to protect unique aspects of product design and packaging. This article examines the governing legal principles, with particular emphasis on cases decided by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit (Federal Circuit) and the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB). This article addresses the legal requirements that must be satisfied to protect product design and packaging under trademark law. The article also offers specific recommendations intended to assist you and your clients in achieving trademark protection in this developing area.

Legal Framework

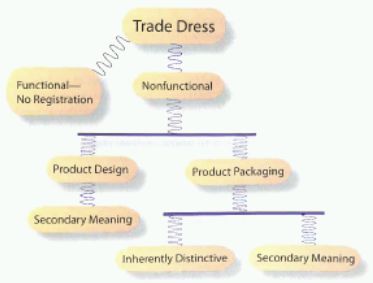

The legal framework used to analyze whether design features--also referred to as trade dress--are entitled to trademark protection can be summarized as follows: First, as a threshold matter, it must be determined whether the claimed trade dress is functional. If so, the trade dress cannot be registered or protected as a trademark. In general terms, a feature is "functional" and cannot serve as a trademark "if it is essential to the use or purpose of the article or if it affects the cost or quality of the article."1 The functionality doctrine limits the types of product configurations and design features that can be registered and protected under trademark law.

If the claimed trade dress is found not to be functional, the party claiming rights must satisfy additional legal requirements before achieving registration or protection. The Supreme Court addressed these requirements in the key case of Wal-Mart Stores, Inc. v. Samara Bros.,2 where the court distinguished between "product-design" trade dress and "product-packaging" trade dress. The two categories can be described as follows:

- "Product-packaging" trade dress is composed of the overall combination and arrangement of the design elements that make up the product's packaging, including graphics, layout, color, or color combinations; and

- "Product-design" trade dress covers a product's shape or configuration and other product design features.

As discussed below, inherent distinctiveness does not entitle product-design trade dress to protection under the trademark laws. Only after product-design trade dress is shown to have acquired secondary meaning will it be entitled to such protection. Product-packaging trade dress, on the other hand, can be protected either if it is inherently distinctive or if it has acquired secondary meaning.

The legal framework outlined above is illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1. Legal framework used in analyzing whether trade dress is entitled to trademark protection.

Product-Design Trade Dress

Generally speaking, product design is more difficult to protect under trademark law than product packaging. The Supreme Court in Wal-Mart recognized that consumers ordinarily do not perceive a product's design as identifying the source of the product; rather, product design generally renders the product itself more useful or more appealing.3 Product-design trade dress can be "inherently distinctive" in the sense that it is arbitrary or fanciful; however, inherent distinctiveness does not entitle product-design trade dress to protection under the U.S. Trademark Act, also known as the Lanham Act. Only after product-design trade dress is shown to have acquired secondary meaning will it be entitled to such protection.4

The practical effect of this rule is that product-design trade dress is not entitled to protection immediately upon first use. Rather, legal protection will attach only after the party claiming rights has used and promoted the product-design trade dress for a period of time, such that consumers have come to associate it with a particular producer or brand; i.e., that secondary meaning has been achieved.

Product-Packaging Trade Dress

The Supreme Court in Wal-Mart observed that, unlike product design, the packaging or "dressing" of a product often is recognized by consumers as identifying the product's source.5 Indeed, "the very purpose of attaching a particular word to a product, or encasing it in a distinctive packaging, is most often to identify the source of the product."6 Product-packaging trade dress can be protected either: (1) if it is inherently distinctive, or (2) if it has acquired secondary meaning. Proof of secondary meaning is not required for product-packaging trade dress that is found to be inherently distinctive.

Distinguishing between Product-Design and Product-Packaging

Distinguishing between product-design and product-packaging trade dress can be difficult. The Supreme Court concluded that, to the extent there are close cases, "courts should err on the side of caution and classify ambiguous trade dress as product design, thereby requiring secondary meaning."7 This rule, which treats "ambiguous trade dress" as product design, requires the party claiming rights to make a showing of secondary meaning in order for the trade dress to be registered and protected under trademark law.

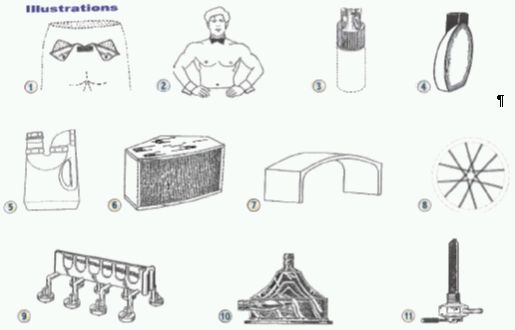

An illustration of the problem can be found in a case in which the Federal Circuit was called upon to distinguish between product design and product packaging, a case involving a design used for clothing. Applicant Slokevage applied to register a trade dress configuration located on the rear of various clothing items. The goods in the application were identified as "pants, overalls, shorts, culottes, dresses, [and] skirts."8 The mark included cut-out areas in the garment and attached flaps with a closure device (see illustration 1).

The applicant chose not to claim secondary meaning under Lanham Act § 2(f), instead arguing that the trade dress was inherently distinctive. Affirming the TTAB, the Federal Circuit concluded that the trade dress was product-design trade dress (rather than product-packaging trade dress) and therefore not eligible for inherent distinctiveness. As such, the trade dress could not be registered absent a showing of secondary meaning. Because Slokevage did not submit evidence of secondary meaning, registration was refused.

The Federal Circuit acknowledged that Wal-Mart did not set forth the factors that distinguish between product-packaging and product-design trade dress. Nevertheless, the court found Wal-Mart informative because it provided examples of trade dress that constitutes product design. Slokevage's proposed trade dress was incorporated into the garment itself and comparable to the trade dress that the Supreme Court in Wal-Mart had classified as product design, not product packaging. The court thus concluded that Slokevage's trade dress constitutes product design, not entitled to protection on the basis of inherent distinctiveness.

Slokevage urges that her trade dress is not product design because it does not alter the entire product but is more akin to a label being placed on a garment. We do not agree. The holes and flaps portion are part of the design of the clothing--the cut-out area is not merely a design placed on top of a garment, but is a design incorporated into the garment itself.9

The mere fact that the proposed trade dress covered only a portion of the product did not prevent it from being product design.

Moreover, while Slokevage urges that product design trade dress must implicate the entire product, we do not find support for that proposition. Just as the product design in Wal-Mart consisted of certain design features featured on clothing, Slokevage's trade dress similarly consists of design features, holes and flaps, featured in clothing, revealing the similarity between the two types of design.10

Determining Whether Product-Packaging Trade Dress Is Inherently Distinctive

The question of whether product-packaging trade dress is inherently distinctive turns on whether consumers, when they first encounter the claimed design, would view it as a source-identifier.11 In determining whether a design is inherently distinctive, the Federal Circuit and the TTAB consider the following four factors, known as the Seabrook factors:

- Whether the design is a common basic shape or design;

- Whether the design is unique or unusual in a particular field;

- Whether the design is a mere refinement of a commonly-adopted and well-known form of ornamentation for a particular class of goods viewed by the public as a dress or ornamentation for the goods; and

- Whether the design is capable of creating a commercial impression distinct from the accompanying words.12

As the Seabrook factors make clear, the more distinct the design is from designs used by others, the more capable the design will be to serve as an indication of source. Thus, a design should not be examined in isolation, but rather in the context of other designs used for the same or similar products.

Trade Dress Found Not to Be Inherently Distinctive

The clear majority of cases addressing this issue find that the asserted trade dress is nothing more than a "variation" or "mere refinement" of other designs, leading to a conclusion that the trade dress does not rise to the level of being inherently distinctive.

In one illustrative case, applicant Chippendales USA, Inc., (Chippendales) sought to register the design of a costume used in providing adult entertainment services for women. The costume consisted of tuxedo wrist cuffs and a bow tie collar without a shirt, referred to as the "Cuffs & Collar" (see illustration 2).

Applying the Seabrook factors, the Federal Circuit affirmed the TTAB's decision and concluded that the mark is not inherently distinctive. The court placed controlling weight on the third Seabrook factor, finding that the Cuffs & Collar design is a mere refinement of or variation on existing trade dress within the relevant field of use. In particular, the court observed that similarities between the Cuffs & Collar design and the previously-used Playboy bunny costume undermined Chippendales' claim of inherent distinctiveness. "[T]he Playboy registrations constitute substantial evidence supporting the Board's factual determination that Chippendales' Cuffs & Collar mark is not inherently distinctive under the Seabrook test."13

A similar result was reached in a case in which Pacer Technology (Pacer) filed a use-based trademark application to register a cap of a container for adhesives and bonding agents. Pacer disclaimed the bottom portion of the adhesive container cap during prosecution. The top portion, which Pacer claimed as its trademark, has a pointed crown from which four equally spaced flat wings extend (see illustration 3).

In concluding that Pacer's adhesive container cap design was not inherently distinctive, the TTAB gave significant weight to 11 U.S. design patents showing drawings of various adhesive container caps. The container caps in these design patents all had a crown, and some had four or six evenly spaced wings around the crown. The TTAB found that the design patents were "probative of the fact that consumers are not likely to find applicant's claimed feature (wings arrayed evenly around a pointed crown) to be at all unique, original or peculiar in appearance."14 The TTAB also found that several of the design patents belonged to Pacer's competitors.

On appeal, the Federal Circuit affirmed the TTAB's decision. The court found that the design patents showing other adhesive container cap designs were sufficient prima facie evidence to support a conclusion that Pacer's design was not unique or unusual in the relevant field and therefore not inherently distinctive. "We agree with the Board that the adhesive container caps in these design patents are 'probative' of the fact that consumers would not find Pacer's adhesive container cap design to be unique or unusual."15

Trade Dress Found to Be Inherently Distinctive

The more peculiar and arbitrary a design is in relation to the underlying goods or services, the more likely the design will qualify as inherently distinctive.

An apt example of an inherently distinctive design can be found in one case in which the applicant applied to register as a trademark the configuration of a container for goods identified as "bath salts, bath powders, shower gels, body oils, bath oils, body lotions, and creams."16 The drawing in the trademark application is pictured in illustration 4.

The applied-for bottle design was unlike other containers on the market and had won a coveted award in an annual competition sponsored by the National Association of Container Distributors. The TTAB found that the configuration of the bottle "is not merely an uncommon design, but is unique and unusual in the field of cosmetics and not a mere refinement of existing designs."17 Accordingly, the Board granted registration, finding the configuration mark to be inherently distinctive.

In another case, the TTAB found that a container for liquid drain opener shaped to resemble a drain pipe was inherently distinctive. The shape of the container is pictured in illustration 5.

The TTAB noted that the configuration of the container was "extremely eye-catching," and "would serve, per se, to identify applicant's product on the shelves of the retail outlets in which it is sold."18

Determining Whether Trade Dress Has Acquired Secondary Meaning

Trade dress that is not inherently distinctive can nonetheless be registered and protected on the basis of secondary meaning. Trade dress acquires secondary meaning when "in the minds of the public, the primary significance of a product feature ... is to identify the source of the product rather than the product itself."19

Several factors are relevant in determining whether a particular mark or design has acquired secondary meaning, including:

- Advertising expenditures,

- Sales success,

- Length and exclusivity of use,

- Unsolicited media coverage,

- Consumer studies linking the term or design to a particular source, and

- Intentional copying.20

Market success of a design, standing alone, generally is insufficient to establish secondary meaning. A product may be popular simply because consumers like the design, even though they do not associate the design with a particular producer or brand.21

Likewise, merely showing a picture of a product in an advertisement, without calling attention to the claimed design features, generally will not support a finding of secondary meaning. Consumers may simply view the advertisement as including a picture of the goods. As one court put it, "[s]econdary meaning cannot be established by advertising that merely pictures the product and does nothing to emphasize the mark or dress."22 Several cases have rejected secondary meaning claims when the advertising includes a depiction of the product, but there is no evidence that consumers would view the depiction as an indication of the source of the goods.

A party seeking to show secondary meaning should show that the asserted design has been promoted as a trademark separate and apart from any word trademarks appearing on the product. For example, advertising that draws attention to the asserted design in a trademark sense (e.g., "look for the [distinctive shape or design]") can strongly support a finding of secondary meaning. [FN23] On the other hand, the lack of "look for" or "image" advertising weighs against a finding of secondary meaning.24

A party also can bolster its showing of secondary meaning by submitting direct evidence of consumer perception in the form of a consumer survey or affidavits or declarations of relevant consumers. Such evidence can be quite persuasive and is preferable to indirect evidence of consumer recognition (e.g., length of use, sales figures, and advertising expenditures), from which inferences of consumer association may be drawn.25

In many secondary-meaning surveys involving design features, it is necessary to remove or cover up from view any house marks or other names, marks or designs that appear on the product stimulus. This masking technique is necessary to measure whether the specific design feature in question (as opposed to another feature) has acquired secondary meaning. The masking technique has been used successfully in a number of secondary-meaning surveys involving trade dress or design features.26

Similarly, to be probative on the issue of secondary meaning, an affidavit or declaration should focus specifically on the design feature that is the subject of the trademark claim. For example, if the applied-for mark is limited to only a portion of a product configuration, the affidavit or declaration should specify that portion, rather than the overall product configuration, as serving to identify the source of the goods. In one case where the declarations failed to identify the applied-for designs with specificity, the TTAB discounted the evidence and found no secondary meaning.

If the customer declarations had specifically referred to the designs shown in the drawings in the specific applications or had described these designs with specificity, the declarations might have had some persuasive value. As it is, they do not persuade us that the particular designs sought to be registered function as trademarks. 27

Recommendations

Experience teaches that efforts to use trademark law to protect product design and packaging often prove unsuccessful. In many cases, the asserted design is found to be functional and therefore ineligible for trademark protection. Even if the functionality hurdle is overcome, trademark protection frequently is denied on the ground that the asserted design is not entitled to protection on the basis of either inherent distinctiveness or secondary meaning.

Against this background, set forth below are four specific recommendations intended to assist you and your clients in achieving trademark protection in this developing area:

- Choose designs that are distinctive and unlike those already in use by others.

- Omit nondistinctive, functional features in defining your trademark.

- Avoid overlap between any utility patent claims and the design feature for which you seek trademark protection.

- Draw attention to the design feature as a mark in advertising.

Choose Designs that Are Distinctive and Unlike Those Already in Use by Others

"You can't make a silk purse out of a sow's ear." A design that is ordinary or common in the trade by definitionwill not rise to the level of being inherently distinctive. In addition, the more common and ordinary the design, the more difficult it will be to prove that the design has acquired secondary meaning.28

Choose designs that are unlike those already in use and that contain distinctive, arbitrary elements. To the extent feasible, the design should incorporate arbitrary or ornamental features--features that do not enhance the product's utility but rather contribute to its unique appearance. Such designs will stand a much better chance of qualifying for protection under the trademark laws.

Omit Nondistinctive, Functional Features in Defining Your Trademark

A party can undermine its ability to obtain trademark protection by claiming rights in the overall design of a product, when that overall design includes nondistinctive, functional elements. The better approach is to seek trademark protection only for the particular features of the design that are ornamental and that serve a source-identifying purpose.

The Federal Circuit counseled against overly broad trademark claims in one case where Bose Corp. sought to register the configuration of a speaker enclosure for "loudspeaker systems."29 The applied-for mark is pictured in illustration 6.

After being refused registration, Bose appealed to the Federal Circuit and argued, among other things, that the curved front edge of the design is an "arbitrary" feature and thus entitled to trademark registration. The court rejected Bose's effort to focus myopically on that single aspect of the design, noting that Bose was seeking to register the design as a whole. In affirming the refusal to register, the court stated:

Bose is seeking protection of its entire pentagonal-shaped design, not only its curved front edges, as made clear by the picture and description of the design in its application for trademark protection. If Bose were only seeking protection of its curved front edge, it would have made that clear in its application for registration.30

Bose does not stand alone--trademark protection frequently has been denied in cases in which the owner sought registration for the overall design of its product rather than for distinct elements or features of the design. Representative examples of these cases include those listed below:

- The configuration of a concrete bridge unit (see illustration 7), found not entitled to trademark protection.31

- The configuration of a spoke pattern in a bicycle wheel (see illustration 8), found not entitled to trademark protection.32

- The configuration of a skin allergy testing device (see illustration 9), found not entitled to trademark

- protection.33

- The configuration of a blood pump (see illustration 10), found not entitled to trademark protection.34

- The configuration of a fuel valve (see illustration 11), found not entitled to trademark protection.35

To increase the likelihood of obtaining trademark protection and registration, the owner should be selective in what it claims as its mark and exclude from the drawing in the trademark application nondistinctive, functional elements that clearly do not serve a trademark function. Dotted lines can be used in the trademark drawing to depict any functional elements or portions of the design that are not claimed as part of the mark.36 This approach focuses the examining attorney's attention on the distinctive aspects of the design that qualify for protection under the trademark laws.37

Avoid Overlap between Any Utility Patent Claims and the Design Feature for which You Seek Trademark Protection

A party should clearly delineate which aspects of its product, if any, are claimed in its utility patents, and which are the subject of trademark protection. By avoiding overlap, the party can use patent law and trademark law in combination to achieve maximum protection.

In TrafFix, the Supreme Court addressed the effect that a utility patent can have on the assertion of trademark rights in a product's design. The Supreme Court held that a utility patent that discloses utilitarian advantages of a claimed design is "strong evidence" that the design is functional and therefore not entitled to trademark protection.38 TrafFix also acknowledged, however, that trademark protection may be available for ornamental aspects of a feature found in a patent claim.

In a case where a manufacturer seeks to protect arbitrary, incidental or ornamental aspects of features of a product found in patent claims, such as arbitrary curves in the legs or an ornamental pattern painted on the springs, a different result might obtain. There the manufacturer could perhaps prove that those aspects do not serve a purpose within the terms of the utility patent.39

The Seventh Circuit elaborated on this point, noting that "[t]he hood ornament on a Mercedes, or the four linked rings on an Audi's grille, would exemplify 'an ornamental, incidental, or arbitrary aspect of the device' that could survive as a trademark even if they once had been included within a patented part of the auto."40

To enhance trademark protection, claims in a utility patent should be carefully drafted so as to exclude any design features for which trademark protection will be sought. This practice will clarify that the design feature in question is not "a useful part of the invention," but rather merely an "arbitrary," "incidental," or "ornamental" aspect of the product.41 The owner will stand on much stronger ground asserting trademark rights in a design feature that is not claimed in its utility patents.42

Draw Attention to the Design Feature in Advertising

Lastly, the trademark holder should use advertising that clearly and unmistakably calls attention to the claimed design as a mark. Advertising that attracts attention to the asserted design feature and encourages the consumer to associate that feature with a single producer will strongly support a trademark claim.

Footnotes

1. Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159, 165 (1995) (quoting Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 850 n.10 (1982)). Courts use the following factors in determining whether a design is functional: (1) the existence of a utility patent disclosing the utilitarian advantages of the design, (2) advertising materials in which the originator of the design touts the design's utilitarian advantages, (3) the availability to competitors of functionally equivalent designs, and (4) facts indicating that the design results in a comparatively simple or cheap method of manufacturing the product. Valu Eng'g, Inc. v. Rexnord Corp., 278 F.3d 1268, 1276 (Fed. Cir. 2002). The first factor--whether the asserted design is the subject of a utility patent--is often the most important. A utility patent that discloses utilitarian advantages of a claimed design is "strong evidence" that the design is functional and therefore not entitled to trademark protection. TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 29 (2001). In many cases, a patent's specification will have strong evidentiary significance because it highlights the functional benefits provided by a feature that falls within the scope of the claimed invention.

2. 529 U.S. 205 (2000).

3. Id. at 213.

4. Id. at 214 (holding that a product design cannot be protected without a showing of secondary meaning).

5. Id. at 209.

6. Id. at 212.

7. Id. at 215.

8. In re Slokevage, 441 F.3d 957, 958 (Fed. Cir. 2006).

9. Id. at 962.

10. Id.

11. In re Chippendales USA, Inc., 622 F.3d 1346, 1352 (Fed. Cir. 2010); In re Pacer Tech., 338 F.3d 1348,1350 (Fed. Cir. 2003); Tone Bros. v. Sysco Corp., 28 F.3d 1192, 1206 (Fed. Cir. 1994).

12. Seabrook Foods, Inc. v. Bar-Well Foods Ltd., 568 F.2d 1342, 1344 (C.C.P.A. 1977). Other cases applying the Seabrook factors in determining whether claimed trade dress is inherently distinctive include the following: Chippendales, 622 F.3d 1346; Pacer Tech., 338 F.3d 1348; and Tone Bros., 28 F.3d 1192.

13. Chippendales, 622 F.3d at 1356-57.

14. Pacer Tech., 338 F.3d at 1349.

15. Id. at 1352.

16. In re Creative Beauty Innovations, Inc., 56 U.S.P.Q.2d 1203, 1204 (T.T.A.B. 2000).

17. Id. at 1208.

18. In re Days-Ease Home Prods. Corp., 197 U.S.P.Q. 566, 568 (T.T.A.B. 1977); see also Imagineering, Inc. v. Van Klassens, Inc., 53 F.3d 1260, 1264 (Fed. Cir. 1995) ("The record showed that the WEATHEREND furniture's singular appearance identified Imagineering as the furniture's source. Thus the record evidence supports the jury's finding of inherent distinctiveness.").

19. Qualitex Co. v. Jacobson Prods. Co., 514 U.S. 159, 163 (1995) (quoting Inwood Labs., Inc. v. Ives Labs., Inc., 456 U.S. 844, 851 n.11 (1982)).

20. In re Steelbuilding.com, 415 F.3d 1293, 1300 (Fed. Cir. 2005).

21. Braun, Inc. v. Dynamics Corp. of Am., 975 F.2d 815, 827 (Fed. Cir. 1992); Cicena Ltd. v. Columbia Telecomms. Grp., 900 F.2d 1546, 1551 (Fed. Cir. 1990).

22. Ohio Art Co. v. Lewis Galoob Toys, Inc., 799 F. Supp. 870, 883 (N.D. Ill. 1992) (Shadur, J.).

23. In re Data Packaging Corp., 453 F.2d 1300, 1304 (C.C.P.A. 1972); In re Hehr Mfg. Co., 279 F.2d 526, 528 (C.C.P.A. 1960).

24. First Brands Corp. v. Fred Meyer, Inc., 809 F.2d 1378, 1383 (9th Cir. 1987); Seabrook Foods, Inc. v. Bar-Well Foods Ltd., 568 F.2d 1342, 1346 n.13 (C.C.P.A. 1977).

25. To be sure, the absence of a consumer survey does not necessarily preclude a finding of secondary meaning. Yamaha Int'l Corp. v. Hoshino Gakki Co., 840 F.2d 1572, 1583 (Fed. Cir. 1988) (noting that "absence of consumer surveys need not preclude a finding of acquired distinctiveness"). Nevertheless, a consumer survey on the issue of secondary meaning can prove decisive in a close case, while the absence of a survey can work against the party claiming trademark rights. Braun, 975 F.2d at 827 ("Braun proffered no surveys, quantitative evidence or testimony suggesting the existence of secondary meaning as to the blender design.").

26. See, e.g., Brunswick Corp. v. Spinit Reel Co., 225 U.S.P.Q. 62, 64 (N.D. Okla. 1984), aff'd, 832 F.2d 513 (10th Cir. 1987).

27. In re Petersen Mfg. Co., 2 U.S.P.Q.2d 2032, 2035 (T.T.A.B. 1987); see also In re Ennco Display Sys., Inc., 56 U.S.P.Q.2d 1279, 1284 (T.T.A.B. 2000) (giving declarations limited probative value on the issue of secondary meaning because they failed to specify the particular features of the applied-for configurations that serve to identify and distinguish applicant's products from those of others); In re Sandberg & Sikorski Diamond Corp., 42 U.S.P.Q.2d 1544, 1549 (T.T.A.B. 1996) (finding declarations to be "of limited probative value" on the issue of secondary meaning because they failed to specify the specific design feature for which registration was sought).

28. Yamaha, 840 F.2d at 1581 (discussing more rigorous evidentiary requirements for proving secondary meaning in ordinary, nondistinctive terms and designs); In re Water Gremlin Co., 635 F.2d 841, 844 (C.C.P.A. 1980) ("One who chooses a commonplace design for his package ... must expect to have to identify himself as the source of goods by his labeling or some other device.").

29. In re Bose Corp., 476 F.3d 1331, 1332 (Fed. Cir. 2007).

30. Id. at 1336.

31. Kistner Concrete Prods., Inc. v. Contech Arch Techs., Inc., 97 U.S.P.Q.2d 1912, 1924 (T.T.A.B. 2011).

32. In re Dietrich, 91 U.S.P.Q.2d 1622, 1635 (T.T.A.B. 2009).

33. In re Lincoln Diagnostics Inc., 30 U.S.P.Q.2d 1817, 1823-24 (T.T.A.B. 1994).

34. In re Bio-Medicus Inc., 31 U.S.P.Q.2d 1254, 1260 (T.T.A.B. 1993).

35. In re Pingel Enter. Inc., 46 U.S.P.Q.2d 1811, 1817 (T.T.A.B. 1998).

36. Trademark Rule 2.52(b)(4), 37 C.F.R. § 2.52(b)(4); U.S. PATENT & TRADEMARK OFFICE, TRADEMARK MANUAL OF EXAMINING PROCEDURE § 1202.02(c)(1) (8th ed. 2011). Examples of acceptable language that has been used for this purpose include the following: In re Gibson Guitar Corp., 61 U.S.P.Q.2d 1948, 1950 (T.T.A.B. 2001) ("[T]he mark [consists of] a fanciful design of the body of a guitar .... [T]he matter shown by the dotted lines is not a part of the mark and serves only to show the position of the mark on the goods."); and In re Ennco Display Sys., Inc., 56 U.S.P.Q.2d 1279, 1280 n.2 (T.T.A.B. 2000) ("The mark consists of the configuration of an eyeglass lens holder. The dotted lines shown in the drawing represent handles which are attached to the lens holder but do not form part of the mark.").

37. In re Vico Prods. Mfg. Co., 229 U.S.P.Q. 364, 366-69 (T.T.A.B. 1985), request for reconsideration denied, 229 U.S.P.Q. 716 (T.T.A.B. 1986) (refusing registration where the applicant sought to register the "entire configuration" of its venturi body for a whirlpool jet, rather than limiting its claim to the essential feature of the design that applicant asserted to be arbitrary); In re R.M. Smith, Inc., 219 U.S.P.Q. 629, 633 (T.T.A.B. 1983) (refusing registration of applicant's entire product configuration, but noting that applicant could have limited its application drawing to arbitrary and nonfunctional features, with the unclaimed features shown in dotted lines), aff'd, 734 F.2d 1482 (Fed. Cir. 1984).

38. TrafFix Devices, Inc. v. Mktg. Displays, Inc., 532 U.S. 23, 29 (2001).

39. Id. at 34.

40. Eco Mfg. LLC v. Honeywell Int'l, Inc., 357 F.3d 649, 653 (7th Cir. 2003); see also In re Udor U.S.A. Inc., 89 U.S.P.Q.2d 1978, 1982 (T.T.A.B. 2009) ("The product features shown and described in the trademark configuration design [depicting a spray nozzle] do not serve a function within the terms of the utility patent, and are not shown as useful parts of the claimed invention."); In re Zippo Mfg. Co., 50 U.S.P.Q.2d 1852, 1854 (T.T.A.B. 1999) (finding that the utility patent claims were directed to the internal mechanism of a cigarette lighter, not the configuration of the lighter).

41. TrafFix, 532 U.S. at 29.

42. Unlike a utility patent, a design patent is directed to the ornamental appearance of an article and does not protect function. Because a design patent is granted only for a design that is primarily ornamental and not functional, the existence of the design patent, while not dispositive, weighs against a finding that the claimed design is functional and thus is consistent with trademark protection. E.g., In re Morton-Norwich Prods., Inc., 671 F.2d 1332, 1342 n.3 (C.C.P.A. 1982); see also Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. v. Interco Tire Corp., 49 U.S.P.Q.2d 1705, 1716 (T.T.A.B. 1998).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.