Introduction

It is the rare civil case that goes all the way to trial, let alone in the trademark world. Of the approximately 260,660 federal civil cases filed each year — 3,120 of which are trademark litigations (or 1.2%) — only 0.8% reach trial.1 Looking just at the subset of trademark cases, only 0.9% go the distance. That's .0010% of all civil actions. Commenting on the scarcity of civil trials generally, Justice Gorsuch recently noted in a Supreme Court oral argument that: "we used to live in a world of trials. Now nobody wants to try — everybody wants to do everything on the papers."2

For those trademark cases that go to trial, it is strategically important — sometimes critical — to determine if the case should be heard by a jury or a judge because the results between the two may differ starkly. For example, in Gateway, Inc. v. Companion Products, Inc., Gateway asserted its rights in a black-and-white cow spot motif/trade dress against Companion Products, Inc. ("CPI") for offering a black-and-white spotted plush toy that wrapped around computer monitors.3

After dropping its damages claim, Gateway moved to strike the jury on the ground that there was no constitutional right to a jury trial.4 The court agreed, but empaneled an "advisory jury."5 After a full trial, the advisory jury found that although Gateway's mark was famous, CPI's product did not infringe or dilute Gateway's rights.6 The court ultimately disregarded the verdict and instead found in Gateway's favor on the issue of infringement.7

Had the jury not been an advisory one, the judge would have been required to give the verdict considerable deference.8 But because the judge was free to do with the verdict what she pleased, this case demonstrates the potentially vast differences in the way juries and judges can adjudicate the very same issue. That is certainly so for trademark cases, which routinely involve judgment calls — on real-life issues that impact everyday consumers — upon which reasonable minds can differ.

From the dearth of trademark cases that go to trial, this year gave us three interesting cases with varying results. This article discusses them.

The Cases

Under Armour, Inc. v. Armorina, Inc. (D. Md.)

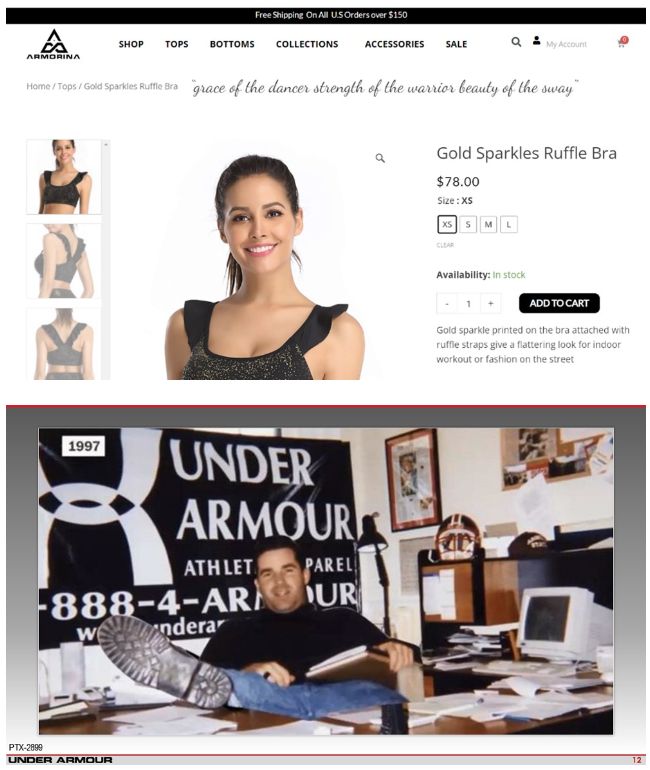

In August 2019, well-known apparel company Under Armour filed suit against Armorina, a small women's apparel company, in the U.S. District Court for the District of Maryland.9 Under Armour alleged that the defendant's use of the ARMORINA name and mark to sell and promote women's athleisure, namely, sports bras and leggings, (shown below) infringed Under Armour's ARMOUR, UNDER ARMOUR, and family of ARMOUR-formative marks, and also diluted its famous UNDER ARMOUR mark.

The parties filed summary judgment motions on various claims, which the court denied. So, the case went forward to trial before a Baltimore jury.

In cases where there's a considerable disparity in resources and size between the two parties, it is always possible that jurors could reflexively think "David and Goliath" and favor the smaller party, even if subconsciously. To combat this sentiment, Under Armour emphasized its humble and remarkable beginnings by focusing on its founder, Kevin Plank, starting the company from his grandmother's basement.

From there, to demonstrate the extent and scope of its rights, Under Armour took the jury on a tour of its meteoric rise to success, introducing testimony and over 1,000 exhibits chronicling its history; various trademark registrations; use of myriad ARMOUR marks (which sit at the core of Under Armour's branding); and extensive women's products, advertising, initiatives, collaborations, and endorsers (including Gisele Bündchen, Misty Copeland, and Lindsey Vonn).

For her part, the defendant's owner — a designer who has lived in New York for years and went to the prestigious Parsons School of Design — claimed that she did not know about Under Armour when she selected ARMORINA. Rather, she said she was inspired by the "armor" worn by medieval knights and combined that term with the last three letters of the word "ballerina" to create an athleisure brand that would inspire and empower women.

In response, Under Armour showed that it has partnered with Parsons, hired Parsons employees, and maintained a significant presence in New York, including in the gym where the defendant's principal worked out.

On the ballerina and women-empowerment points, Under Armour presented to the jury its partnership and collaborations with famed ballerina Misty Copeland, including the fashion-forward collections Under Armour created with her. And to counter the defendant's contention that its athleisure apparel was fundamentally different from Under Armour's because of its designs, Under Armour walked the jury through some of the many advertising campaigns it has run in the past to inspire and empower women.

It also presented evidence that the defendant's endorsers posted videos of themselves lifting weights in defendant's clothes, as well as pictures on Instagram showing that they often wore Under Armour clothes.

The defendant also focused on the lack of a "U" in its ARMORINA name and mark. Under Armour responded by providing evidence that many people — from consumers, to endorsers, to reporters, to even advertising agencies — spell UNDER ARMOUR without the U (i.e., UNDER ARMOR).

The defendant also argued that its mark did not conflict with Under Armour's rights because it used a triangle logo design that differed from the Under Armour logo. Under Armour countered by pointing to instances where the defendant did not use its logo and also showed jurors the varied logos Under Armour has used with its ARMOUR marks and collaborations.

Finally, to further address the "David and Goliath" concern, and to show the jury that Under Armour was not trying to put the defendant out of business, it asked for just $1 in damages. All the while, Under Armour emphasized that it had a responsibility to enforce its trademarks; otherwise, it could lose them — a duty the defendant's own clearance counsel conceded.

After four days of trial, the Baltimore jury agreed with Under Armour on all counts, ruling that Under Armour's UNDER ARMOUR mark is famous and Armorina's use of the ARMORINA mark constitutes trademark infringement, unfair competition, and trademark dilution. It also awarded Under Armour the $1 it asked for.

Hermès Int'l v. Rothschild (S.D.N.Y.)

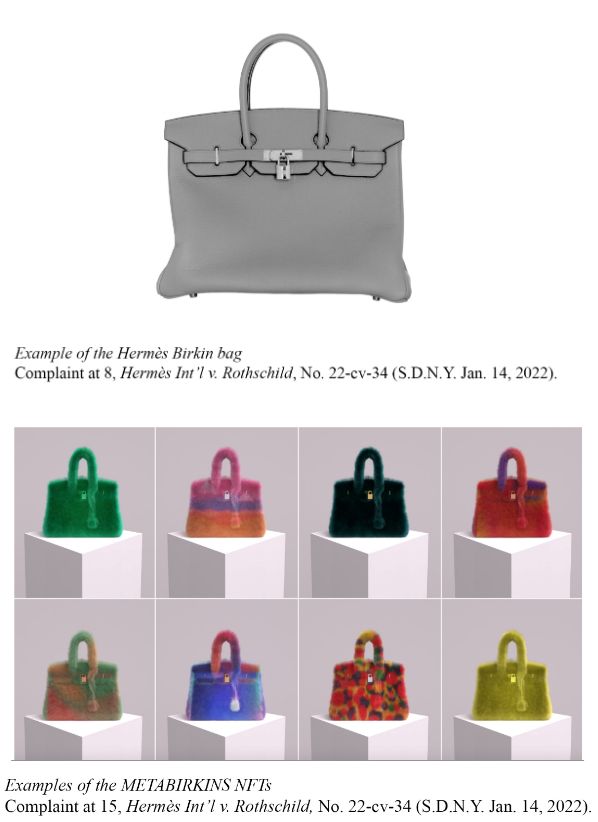

In this highly publicized trademark case, luxury fashion house Hermès sued "interdisciplinary artist and designer" Mason Rothschild after he began selling non-fungible tokens ("NFTs")10 displaying the Hermès "Birkin Bag" and using the designation METABIRKINS.11 When first minted, the NFTs generated around $800,000 from trading on OpenSea — one of the largest NFT marketplaces.

In addition to asserting infringement and dilution of its BIRKIN mark, Hermès alleged that Rothschild infringed its trade dress for the Birkin Bag (the bag's overall shape and design). Hermès claimed that Rothschild planned to use the METABIRKINS name to brand his "metaverse" business activities, trading on the value and fame of the BIRKIN mark and trade dress in real life. Hermès also alleged cybersquatting.

Rothschild moved to dismiss, raising a First Amendment defense to Hermès's trademark infringement and dilution claims under the "Rogers" test, derived from Rogers v. Grimaldi.12 In that case, the Second Circuit held that the use of a mark in an expressive work is protected speech and thus non-infringing (even when sold for profit) where: (1) the work is artistically relevant, and (2) the use is not "explicitly misleading."

Rothschild argued the METABIRKINS NFTs are artistically relevant because by portraying furry handbags, they comment on animal cruelty in the fashion industry and the new search for leather alternatives. He further argued that METABIRKINS NFTs are not explicitly misleading because they do not expressly suggest an endorsement by Hermès.

Rothschild also relied on the Supreme Court's decision in Dastar,13 which held that only misrepresentations of the source of physical goods are actionable under the Lanham Act.14 He argued the METABIRKINS artworks are "communicative goods that Dastar places outside the scope of the Lanham Act."15

Denying Rothschild's motion to dismiss, the court held that Hermès's amended complaint included sufficient allegations that Rothschild intended to associate the METABIRKINS mark with the popularity and goodwill of Hermès's BIRKIN mark. The court cited statements Rothschild made in an interview that he "wanted to see as an experiment if [he] could create that same kind of illusion that [the Birkin Bag] has in real life as a digital commodity."16

Following the motion to dismiss, the parties filed cross-motions for summary judgement. There, the court addressed the merits of Rothschild's First Amendment Rogers defense. The court found that there was a genuine issue of material fact as to whether "Rothschild's decision to center his work around the Birkin bag stemmed from genuine artistic expression or, rather, from an unlawful intent to cash in on a highly exclusive and uniquely valuable brand name."17

The court further found that the issue of artistic relevance is a mixed question of fact and law that is particularly well-suited for jury determination and, because reasonable minds could differ, the court denied both parties' summary judgment motions on the issue. The court also denied summary judgment to both parties on the issue of explicit misleadingness, finding that adjudicating this issue would require the application of the Second Circuit's Polaroid factors for likelihood of confusion — a fact-intensive inquiry also best left to the jury.

In January 2023, the case was tried to a jury, which found Rothschild liable on all counts (trademark infringement, trademark dilution, and cybersquatting) and concluded that the First Amendment did not bar liability. The jury awarded Hermès $110,000 in lost profits for the trademark infringement and dilution claims, and $23,000 in statutory damages for the cybersquatting claim.

adidas Am., Inc. v. Thom Browne, Inc. (S.D.N.Y.)

In this case involving another large sportswear manufacturer, adidas sued luxury fashion brand Thom Browne for selling athletic style apparel and shoes that featured two, three, and four stripes,18 claiming they infringed and diluted adidas's three parallel stripe trademark, which adidas has used on its products since the early 1950s. Historically, Thom Browne designs have also featured parallel stripes, one of which — referred to as the "Grosgrain Signature" — is a pattern of five white-red-white-blue-white stripes. Significantly, in around 2005, Thom Browne used another design — referred to as the "Three-Bar Signature" — comprised of three parallel lines of similar width and proximity.

After adidas expressed concern about possible infringement, Thom Browne stopped using the Three-Bar Signature design. Beginning in 2009, Thom Browne debuted the Four-Bar Signature design, which featured four large stripes on luxury goods, primarily sold in high-end department stores like Barney's and Bergdorf Goodman. In 2010, Thom Brown expanded its use of the Four-Bar Signature to activewear. Between 2011 and 2018, when some of the activewear featured the mark at issue, Thom Browne's activewear sales increased from 15% in 2011 to 27.5% in 2018.

Adidas claimed it learned of the Four-Bar Signature design in 2018 and, after failed attempts at negotiation and mediation, adidas sued on June 28, 2021, in the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of New York. adidas specifically alleged that Thom Browne infringed the Three-Stripe Mark by "offering for sale and selling athletic-style apparel and footwear featuring two, three, or four parallel stripes in a manner that is confusingly similar to adidas's Three-Stripe Mark ... ."19

In response, Thom Browne asserted various affirmative defenses, i.e., that adidas was barred by laches, acquiescence, and estoppel and that adidas abandoned the Three-Stripe Mark. Both parties filed cross-motions for summary judgment on the affirmative defenses.

The Court granted summary judgment for adidas, dismissing Thom Browne's defenses of acquiescence, estoppel, and abandonment, but denied summary judgment to either party on the laches defense because there were genuine disputes of material fact.

The case then proceeded to trial before a jury. At trial, adidas argued that the parties' use of the marks appeared in the same way on social media and e-commerce, and that unless Thom Browne's Four-Stripe apparel included a clear reference to Thom Browne, there was a risk of confusion.

Additionally, adidas relied on a consumer survey that showed 26.9% of respondents believed adidas was the manufacturer of certain Thom Browne athletic pieces with the Four-Stripe pattern. Regarding intent, adidas argued that Thom Browne partnered with previous adidas-sponsored individuals and organizations, like the FC Barcelona soccer club, Lionel Messi, and the Cleveland Cavaliers.

For its part, Thom Browne argued that its designs featured a varying number of stripes and that stripes are common for clothing. It also argued that confusion was unlikely because the two companies' price points are vastly different — Thom Browne sells luxury goods that are priced higher than adidas's goods — and the prospective markets and consumers differ.

In the end, and on the same day the Baltimore jury ruled for Under Armour in the Armorina case, the Manhattan jury ruled against adidas, finding it failed to show that Thom Browne's use of the Grosgrain Signature and Four-Stripe designs violated adidas's Three-Stripe Mark because they were not likely to cause consumer confusion. adidas has appealed the case to the United States Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit.

Conclusion

Although the vast majority of trademark cases do not make it to trial, litigators must still plan for that possibility from day one. And because the things that matter to jurors may not matter to judges (or vice versa), the decision on whether to request a jury should not be taken lightly — as seen by the result of Gateway Inc. v. Companion Products, Inc. For those cases that go the distance, lawyers must test and hone their themes in advance so that they can present a persuasive, concise, and impassioned (where appropriate) story that gives jurors the tools to rule their way.

Footnotes

1. United States Courts, U.S. District Courts — Civil Cases Terminated, by Nature of Suit and Action Taken — During the 12-Month Period Ending March 31, 2023, Table C-4 — U.S. District Courts — Civil Federal Judicial Caseload Statistics (Mar. 31, 2023), https://bit.ly/3ZrmixU (last visited Sept. 21, 2023).

2. Transcript of oral argument at 43:55, Dupree v. Younger, 143 S. Ct. 1382 (2023), (No. 22-210), https://bit.ly/44VS2fO.

3. Gateway Inc. v. Companion Prods. Inc., 68 U.S.P.Q.2D (BNA), (D.S.D. Aug. 19, 2003) modified, No. 01-cv-4096, (D.S.D. Dec. 19, 2003), aff'd 384 F.3d 503 (8th Cir. 2004).

4. Under the Seventh Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, the right to a jury trial attaches to civil cases in which legal claims and remedies are asserted, not on those that assert purely equitable claims and remedies. G.A. Modefine S.A. v. Burlington Coat Factory Warehouse Corp., 888 F. Supp. 44, 45 (S.D.N.Y. 1995) (internal citation omitted). In trademark cases, the right to a jury trial arises when claims for actual damages are requested under 15 U.S.C.A. § 1117. See New Century Fin., Inc. v. New Century Fin. Corp., No. C-04-437, , at *1 (S.D. Tex. Dec. 13, 2005).

5. For advisory juries, ”[t]he responsibility for the decision rendering process remains with the judge even though an advisory jury is used. The court must prepare the findings of fact and conclusions of law, and it is in its discretion wholly whether to accept or reject, in whole or in part, the verdict of the jury.” Indiana Lumbermens Mut. Ins. Co. v. Timberland Pallet & Lumber Co., 195 F.3d 368, 376 (8th Cir.1999) (internal citation omitted).

6. Gateway Inc., , at *1. (The author represented Gateway in this case.)

7. Id. at *22.

8. Unlike an advisory jury, the verdict from a “regular” jury cannot be disturbed absent a determination that “a reasonable jury would not have a legally sufficient evidentiary basis to find for the [prevailing] party.” See Fed. R. Civ. P. 50(a) and (b).

9. Under Armour v. Armorina, No. 1:19-cv-02417 (D. Md.). The author represented Under Armour in this case.

10. As the court noted, NFTs are “digital records of ownership, typically recorded on a publicly accessible ledger known as a ‘blockchain.' On the blockchain, an NFT functions as a sort of ‘digital deed' representing ownership in a physical or digital asset or assets. Here, each of the NFTs signified sole ownership of a particular ‘MetaBirkin,' that is, a unique digital image of a Birkin handbag rendered by Rothschild.” Hermès Int'l v. Rothschild, No. 22-cv-384 (JSR), , at *2 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 2, 2023) (internal citation omitted).

11. Hermès Int'l v. Rothschild, No. 22-cv-34, complaint filed, (S.D.N.Y. Jan. 14, 2022).

12. Rogers v. Grimaldi, 875 F.2d 994 (2d Cir. 1989).

13. Dastar Corp. v. Twentieth Century Fox Film Corp., 539 U.S. 23 (2003).

14. Id.

15. Memorandum of Law in Support of the Defendant Mason Rothschild's Motion to Dismiss the Amended Complaint at 21, Hermès Int'l v. Rothschild, 603 F. Supp. 3d 98 (S.D.N.Y. May 18, 2022) (No. 1:22-cv-00384-AJN-GWG).

16. Hermès Int'l, 603 F. Supp. 3d at 101 (internal citation omitted).

17. Hermès Int'l v. Rothschild, No. 22-cv-384 (JSR), , at *8 (S.D.N.Y. Feb. 2, 2023).

18. adidas Am., Inc. v. Thom Browne, Inc., No. 21-cv-5615 (JSR), , at *3 (S.D.N.Y. Dec. 16, 2022).

19. Complaint ¶ 4, adidas Am., Inc. v. Thom Browne, Inc., 629 F. Supp. 3d 213 (S.D.N.Y. June 28, 2021) (No. 21-cv-5615), .

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.