Given the sheer scale of activities that companies are moving offshore these days, decisions on how to configure operations can have an unprecedented impact on shareholder value. Yet time and again, large corporations are making these decisions with insufficient clarity. The most egregious oversight: assuming that migrating operations offshore requires outsourcing them to another company.

This thinking can put significant value at risk. Global outsourcing is not always a better alternative to going it alone offshore or teaming up with a partner overseas. On the contrary, companies that set up their own operations in low-cost regions increasingly generate returns comparable to or higher than companies that outsource. What’s more, the delivery risk of putting a viable operation in place may actually be lower than that of outsourcing.

Companies cite myriad reasons for outsourcing, but often there are sound strategic, operational and economic arguments for going offshore yourself and retaining at least partial control and/or ownership of operations. The key challenge to making the right move is to separate the offshoring decision from the outsourcing one.

Based on our experience with a number of multinationals that have faced this choice, we believe that managers must first decide which operations to shift offshore, and then identify the most effective means of taking action – i.e., whether to own those operations outright, outsource them or do something in between like a joint venture. Only after rigorously evaluating alternative offshoring business models and understanding the true end-to-end economics of each alternative will managers arrive at the best answer for increasing their companies’ long-term value.

Outsourcing Is Not the Only Option

Western managers wary of establishing new operations in foreign environments can choose from a range of pretexts to avoid in-house offshore solutions: "It’s too hard." "It’s too risky." "We don’t have the scale." "It’s too capital-intensive." "It’s not our core business."

Those managers can gain comfort from innumerable case studies (peddled by big consulting firms and outsourcing providers) showing that outsourcing is the quickest and safest way to migrate operations offshore. Many of the world’s leading multinationals have successfully outsourced major pieces of their businesses – customer service, manufacturing, IT development, tech support and even product engineering – to these firms in India and elsewhere. The meteoric rise of specialist IT service providers such as Infosys and Wipro has fueled the growth of India as the world’s favored outsourcing hub. Global IT consultants have prospered too by helping companies move IT operations offshore, often to their own service centers.

Yet as offshoring has flourished, it has also become more manageable. The political and regulatory environments of host countries have eased considerably (most notably in India). At the same time, the flexibility and skill-level of local labor markets have increased without losing cost competitiveness (again, India stands out). Finally, shareholders and lenders have become less nervous about major investments in remote emerging markets.

As a result of these changes, the decision to migrate operations offshore need not require outsourcing them to a third party. Large companies should carefully consider a variety of offshore business models before choosing one. In doing so, many will find that they can capture the maximum value potential of offshoring by creating a wholly owned subsidiary or joint venture rather than by pursuing a fully outsourced model – and that doing it themselves need not be any more complex or risky than outsourcing to a third party.

An In-House Alternative

The decision to run an operation or outsource it hinges on three critical factors: the ability of the management team to manage the migration; the economics of the alternative operating models; and the extent to which the activities are "core" (i.e., crucial to day-to-day operations).

Managing the Offshore Move

A common argument for outsourcing is that shifting operations offshore is simply too complex, time-consuming and risky to be done by busy management. However, there are now plenty of case studies of companies that have successfully established their own facilities offshore. Take Britain’s Standard Chartered bank and insurer Prudential plc. Both have set up wholly owned centers in India and have migrated a substantial part of their business processes there. Standard Chartered employs over 2,500 staff performing a full range of banking and support functions at its global processing hub in Chennai (formerly Madras). Prudential employs around 850 policy administration and customer service staff at its center in Mumbai (formerly Bombay). Both operations cite control of critical business processes, access to abundant skilled manpower and significant cost savings as key drivers of their success, and both are planning further expansion of their facilities.

The rapid growth of offshore operations in places like Mumbai, Bangalore and Guangzhou has encouraged speculative property developers to build commercial space suitable for most offshore operations. At the same time, an entire industry has emerged to provide set-up assistance to overseas companies. This allows firms to tap valuable local knowledge on property selection, equipment import and procurement, staff recruiting and so forth, typically at low cost. The availability, quality and experience of turnkey contractors mean that companies can outsource the building and staffing of their facility without surrendering ownership or management control.

Of course, establishing an owned facility in an emerging market such as India is not without risk. The major external risks are geopolitical (e.g., the threat of armed conflict, political unrest, etc.) and are thus equally applicable to outsourced and in-house operations. Another risk both models share is the threat of sudden adverse changes in the regulatory or tax regime. (It’s worth noting, however, that the rising contribution of offshoring to host nations’ economies provides a natural hedge against this threat.) Most business risks, on the other hand, are more easily managed internally through adherence to strict compliance procedures and rigorous staff training processes – a benefit companies cede when using third-party providers.

In fact, a wholly owned facility may actually reduce risk if that facility is con figured to provide offshore backup and disaster recovery in the event of an onshore failure. Moreover, third-party providers seek to minimize their own business risk, often by demanding contracts with lengthy lock-in periods and lenient service level agreements.

The Full Economics Are Worth Capturing

The capital investment necessary to establish an in-house operation in a foreign country is often cited as a key reason to outsource: Companies can exploit their vendors’ in-place assets (property, staff, IT/telecommunications) rather than make these significant investments on their own. That said, most offshore operating costs (the majority of which relate to labor, property and telecoms) are essentially variable with the number of staff, particularly if property is leased rather than bought outright. Minimum efficient scale is generally modest given the wide (and well-documented) differences in unit labor costs between onshore and offshore locations. The growing availability of skilled labor and commercial properties for rent makes offshore operations highly scalable in established host centers such as Mumbai.

While outsourcing providers’ size may give them lower unit operating costs than a company can achieve on its own, the third party typically captures a significant share of the end-to-end cost savings. Keeping a bigger slice of such operating savings may well offset any incremental set-up and unit operating costs incurred by the do-it-yourself alternative. In our experience, offshore outsourcing providers typically command margins of 20-40% of pro forma net savings relative to onshore operating costs: This amounts to a substantial ongoing "fee" which may well be worth recovering. (That the outsourcing market in India is so profitable is a testament to the size of the prize on offer: India’s Infosys achieved a 31% operating margin in 2003.) A do-it-yourself approach may also allow the firm to capture one-off duty waivers on imported capital equipment (as is currently the case in India), which would otherwise go to the third-party provider.

The capital implications for those going it alone depend largely on what activities are being moved offshore. A pharmaceutical research lab will clearly require much higher investment than a back-office processing or call center. Capital requirements even for the latter can be significant, with $20 million-$30 million typically needed to establish a 1,000-seat facility. That said, site development times have become compressed in established host cities like Mumbai, and resulting savings means companies may recoup costs quickly. A capable project team should require only four to six months to establish a 1,000-seat call center operation in Mumbai, which will typically make a profit within two to three years of launch.

It Is Your Core Business

In the early days of offshore outsourcing, companies tended to migrate activities such as software development and IT support that could be isolated from day-to-day operations and were not deemed "business critical." This was due in part to a reluctance to expose the company to unknown risk, a lack of local skills in more demanding activities and unreliable communications links between the host and home country. Today, the delivery risks have become better understood, the local skills base has broadened and the communications infra structure is robust.

As a result, companies are increasingly moving core activities such as scientific research, new product development, financial accounting and internal audit to offshore locations. These activities require the ongoing involvement and accountability of senior decision makers within the company. As such, there may be inherent benefit in retaining these activities in-house (whether in an onshore or an offshore environment) rather than passing management control and decision rights to a third party. Where quick decisions are required to sustain competitive advantage, the response times of the offshore operation are likely to be shorter for a wholly owned subsidiary than for a third-party provider – especially if those decisions trigger the renegotiation of an outsourcing contract.

Real Choices Exist

The best way for managers to get to the most effective offshore solution for their business is to separate the "what" from the "how" when they are planning the change. Managers’ first task is to identify what processes and activities should be migrated offshore – irrespective of how that migration will be executed. Their second, separate task is then to determine the full range of offshore alternatives for both implementation and subsequent operations. Third, they should subject each alternative to rigorous, objective evaluation against strategic, financial and organizational criteria. The right offshore business model provides the most appropriate trade-off between ownership, operating flexibility and economics – both at points in time and over time.

|

Four Steps for Arriving at the Best Offshore Solution

|

The final task is to identify what the preferred model will take to deliver in terms of management commitment, capital, capabilities and time. A high-quality execution team can then be assembled with the right skills and incentives to ensure timely delivery.

Consider the experience of one of Europe’s leading financial services firms. In early 2002, the company began to research offshore options in Asia. A core team of four managers was formed to assess the range of choices available. The team first determined the "what" (the activities most suitable for moving offshore, and the sequence in which that should happen), then the "how" (different ownership and operating models, and different migration paths) and then finally the "where" (different locations). In challenging the presumption of outsourcing as the sole offshore solution, the team evaluated an array of operating models from fully outsourced to joint venture to wholly owned.

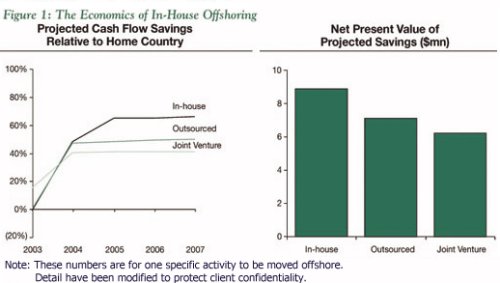

The in-house model emerged as the clear winner, performing strongest against each of the criteria. Strategically, top management determined that the customer-facing activities to be moved offshore were simply too critical to be entrusted to a third party. Financially, the economics strongly favored an in-house solution in which the firm captured all of the significant projected savings (see Figure 1).

And organizationally, the firm had existing Asian operations to soften the cultural impact of shifting activities from Europe to Asia. In parallel, the firm rigorously evaluated potential locations in India, China, Malaysia and elsewhere. It chose Mumbai because the city offered the combination of rapid start-up, skilled labor and ongoing cost savings that best matched the company’s needs.

Once the preferred operating model and host location were identified, a manager with prior offshoring experience was hired from outside the firm to lead the implementation. He and his team assessed a number of local providers in Mumbai and chose one to serve as turnkey contractor to source, equip and staff the new facility. In late 2002, the company decided to proceed, and the facility was opened less than six months later. One year on, the Mumbai operation has exceeded all of its initial operating, service-level and financial performance indicators. The company is looking at other onshore operations to shift to its Mumbai facility.

All this is not to suggest that an in-house offshore model is always more appropriate than an outsourced model. The right answer will depend on the level of management commitment, complexity of operations, internal delivery capabilities and, crucially, how the economics stack up. The point is that managers must objectively evaluate a full range of alternative business models when considering a move offshore. Contrary to received wisdom and the well-publicized claims of the outsourcing industry, businesses that establish their own operations on foreign soil may generate the most attractive strategic, economic and operational benefits over time. Offshore need not, and often should not, mean outsourced.

Marakon Associates advises some of the world’s best-known companies on the issues that most drive their performance and long-term value. The firm’s focus on value creation enables it to bring an original, independent view and unique expertise to the critical challenges business leaders face. Marakon has offices in Chicago, London, New York, San Francisco and Singapore.