- within Food, Drugs, Healthcare and Life Sciences topic(s)

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

- within Food, Drugs, Healthcare and Life Sciences topic(s)

- with readers working within the Automotive and Property industries

- within Real Estate and Construction, Immigration, Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

Executive Summary

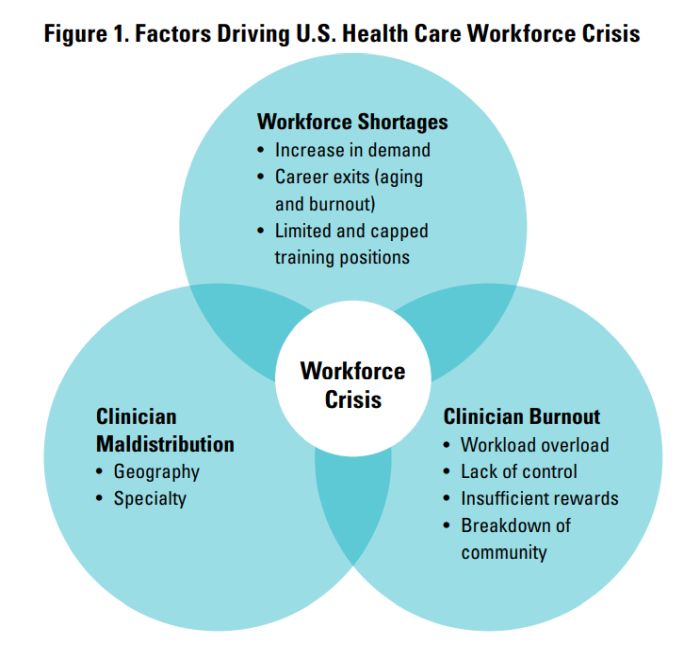

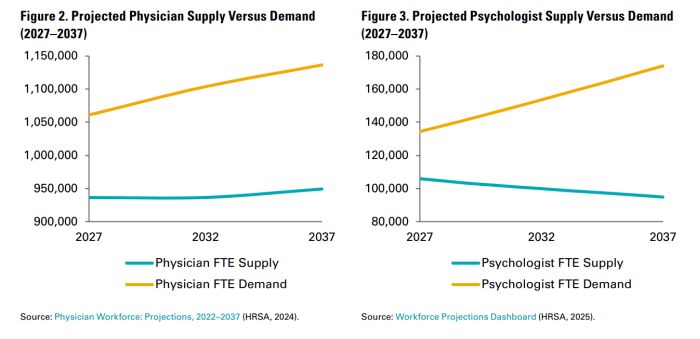

The U.S. health care system is facing a severe and worsening workforce crisis, characterized by a shortage of providers, geographic maldistribution of providers, and record levels of burnout. This crisis spans various clinical specialties and provider types, including physicians, advanced practice providers, registered nurses, and social workers, among others. In 2024, the Health Services and Resource Administration (HRSA) estimated the supply of physicians and registered nurses only met 90% of the total demand for each respective workforce needs, and the problem is only getting worse, with a growing patient population that needs more care and a limited number of providers to care for them. By 2037, HRSA projects that nonmetro areas will experience a 60% shortage of physicians and metro areas a 10% shortage.1 The workforce crisis hinders patient access to necessary care and compromises quality of care, leading to sub-optimal health outcomes.

Telehealth is a promising solution to mitigate the workforce crisis. Telehealth modalities—in particular, virtual nursing, eConsults, and video visits—offer innovative ways to extend the current workforce, expand the geographic reach of providers, and maintain the existing workforce by reducing burnout and improving worklife balance. However, despite this potential, many telehealth programs are sub-scale due to limited coverage and reimbursement, insufficiently robust evidence, cultural barriers around adopting new technology, and other factors.

Even at full scale, telehealth alone will not meaningfully address the workforce crisis. Other emerging technologies, particularly artificial intelligence (AI), have the potential to significantly unlock workforce capacity. AI can assist, augment, and automate certain activities currently performed by clinical and administrative staff, thereby increasing efficiency and improving access. AI tools can streamline clinical documentation, enhance decision support, and automate routine administrative tasks, allowing providers to focus on patient care. AI tools can also be used to accelerate the adoption and impact of promising telehealth models by enabling significant gains in efficiency through automation.

To fully realize the potential of telehealth and AI in addressing the workforce crisis, several key considerations must be addressed. These include establishing clear and consistent reimbursement models, incorporating telehealth and AI into education and training curricula, addressing the digital divide, and investing in research and implementation resources. Additionally, broader policy and industry changes are needed to attract, optimize, and retain health care professionals, including enhancing financial and workplace incentives and prioritizing provider well-being.

While there is no silver bullet to addressing the workforce crisis in the U.S., scaling high-impact telehealth programs and accelerating the adoption of high-value AI can produce meaningful improvements in workforce shortages, maldistribution, and clinician burnout.

National Health Care Workforce Crisis

The United States health care system is facing an evolving workforce crisis, defined by a shortage of providers, a geographic maldistribution of providers, and high levels of burnout. This crisis is multifaceted, spanning both clinical specialties (e.g., primary care, behavioral health) and provider types (e.g., physicians, advanced practice providers, registered nurses, social workers), and is only expected to worsen over the next decade.2,3,4

Given that a robust workforce is core to meeting patient health care needs, the country's ability to ensure access to health care services hinges on the availability of eligible, engaged providers. Ultimately, worsening shortages, maldistribution, and burnout will negatively impact patient access, quality of care, and health outcomes nationally.

Workforce Shortages

In 2024, the HRSA estimated that the supply of physicians and registered nurses only met approximately 90% of the total demand for each respective workforce need.5,6 Societal and demographic trends are expected to exacerbate shortages. The overall U.S. population is expected to grow by 8.4% over the next decade, with the population 75 years or older, who have the greatest and most specialized care needs, expected to grow by 54.7%.7 Concurrent with this rise in patient demand is a fall in physician supply: nearly a third of the current physician workforce is expected to retire over the next decade, with others considering an early exit from the workforce due to burnout.8,9 Additionally, limitations in training opportunities, such as the capped volume of graduate medical education positions, creates barriers for new entry into the workforce.10

Projected Workforce Shortages by 2037 (HRSA):11

- 187,130 physicians

- 207,980 registered nurses (RNs)

- 302,440 licensed practical nurses (LPNs)

- 113,930 addiction counselors

- 87,840 mental health counselors

- 79,160 psychologists

- 9,140 physical therapists

- 17,030 pharmacists

Provider Burnout

In 2023, nearly half of physicians reported experiencing at least one symptom of burnout, with similar rates of burnout seen among nurses and behavioral health workers.12,13,14 Factors fueling burnout include overwhelming workloads, a perceived lack of control over one's work environment, insufficient rewards and recognition, and a breakdown of community and support systems within the health care setting.15 In turn, provider burnout contributes to staffing turnover, reduced clinical hours, and decreased morale16 and costs an estimated $4.6 billion a year.17

Physician burnout has been associated with:18

- 2x increase in patient safety incidents

- 4x decrease in job satisfaction

- 3x increase in turnover intentions

- 3x increase in regret of career choice

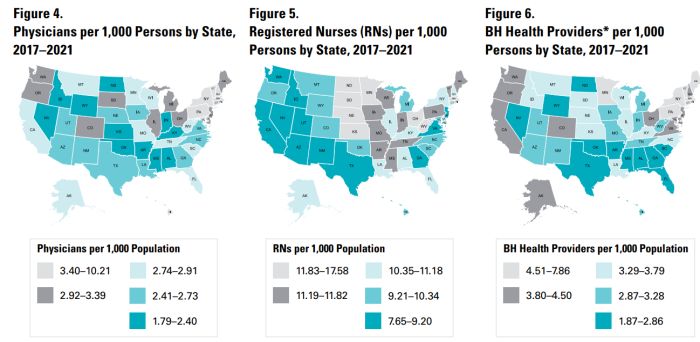

Provider Maldistribution

Provider maldistribution creates uneven access to the already limited supply of providers. There is wide variation by state. For instance, Massachusetts has the most physicians per capita with 466 per 100,000 residents—2.4 times greater than the ratio of physicians to residents in Idaho.19 Geographically, providers— particularly specialists who require access to tertiary clinical centers that are typically located in urban centers—tend to live in more urban areas, leaving many rural and underserved communities to experience the impact of these shortages more acutely. While HRSA estimates that 94% of demand for physician services will be met in metro areas in 2036, less than half of the estimated demand (44%) will be met in non-metro areas.20 Geographic distribution also varies by state or region according to provider type. For example, states in the west have fewer nurses per capita as compared to other parts of the country, while states in the southeast have fewer behavioral health practitioners (Figures 4–6).21

Source: Health Care Workforce: Key Issues, Challenges, and the Path Forward, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Oct. 2024, aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/documents/82c3ee75ef9c2a49fa6304b3812a4855/aspe-workforce.pdf.

*Figure 6 includes Psychologists, Marriage and Family Therapists, Mental Health and Addiction Counselors, and Social Workers.

Recommended Resources to Learn More About the Health Care Workforce

- Health Care Workforce: Key Issues, Challenges, and the Path Forward (ASPE, 2024)

- The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036 (AAMC, 2024)

- Workforce Projections Dashboard (HRSA, 2025)

Telehealth as a Workforce Crisis Mitigator

Opportunities for Telehealth

Telehealth has long been used to mitigate workforce challenges, especially in rural communities which historically lacked access to specialty care. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered explosive growth in telehealth, as policymakers relaxed previous regulatory and reimbursement barriers in efforts to maintain health care access at a time when social distancing was mandated and the health care system was constrained.22 While telehealth utilization has declined since the initial months of the pandemic, telehealth visits have consistently accounted for approximately 5% of ambulatory encounter claims since 2021, with the greatest growth seen in behavioral health.23,24 As telehealth has become more commonplace, health systems are recognizing its opportunities to support workforce challenges in a few key ways:

- Extend the current workforce: Telehealth can

support more efficient use of the current workforce's limited

capacity through the following mechanisms:

- Task shifting: By enabling remote education, supervision, and specialty consultation, telehealth can support reallocating tasks from more specialized providers to other members of the clinical team. Shifting care from specialists to primary care or from physicians to advance practice providers allows team members to work at their top of their license and frees specialized providers to focus on more complex patients.

- Shifting to "one-to-many" models: Traditional care models require one-on-one interactions between a provider and a patient. Some telehealth modalities, such as Virtual Sitters, enable one-to-many care models that allow one provider to care for multiple patients at a time, increasing the provider's ability to oversee the care of more patients efficiently.

- Shifting to asynchronous care: Telehealth programs that rely on secure messaging or remote monitoring allow patient care that traditionally was done in real-time and faceto-face to be done asynchronously. This lessens the pressure on providers' schedules by allowing them to manage routine tasks, such as prescription refills or reviewing labs, outside of a limited supply of appointments and reserve in-clinic time to focus on patients with greater needs.

What is Telehealth?

HRSA defines telehealth as the use of electronic information and telecommunication technologies to support long-distance clinical health care, patient and professional health-related education, health administration, and public health.25

Common uses of telehealth can be classified as occurring Provider-to-Patient (i.e., provider administering direct clinical care to a patient—such as a video/ audio visit or remote physiologic monitoring) or Provider-toProvider (i.e., providing clinical consultation, education, or oversight between providers).

Telehealth can be further characterized by whether an encounter is synchronous (i.e., real-time, two-way encounter) or asynchronous (i.e., exchange of information at different times, sometimes called "store-and-forward).

Note: Definitions for common telehealth programs are included in the report Appendix.

To view the full article click here

Footnotes

1. National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Health Workforce Projections, Bureau of Health Workforce, https://bhw.hrsa.gov/dataresearch/projecting-health-workforce-supply-demand. Accessed 20 Mar. 2025.

2. National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Health Workforce Projections, Bureau of Health Workforce, https://bhw.hrsa.gov/dataresearch/projecting-health-workforce-supply-demand. Accessed 20 Mar. 2025.

3 GlobalData PLC. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036, Association of American Medical Colleges, Mar. 2024, http://www.aamc.org/media/75236/download.

4. Health Care Workforce: Key Issues, Challenges, and the Path Forward, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Oct. 2024, https://aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ documents/82c3ee75ef9c2a49fa6304b3812a4855/aspe-workforce.pdf.

5. "Nurse Workforce Projections, 2022-2037." Health Workforce, HRSA, Nov. 2024, bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-healthworkforce/data-research/nursing-projections-factsheet.pdf.

6. "Physician Workforce: Projections, 2022-2037." Health Workforce, HRSA, Nov. 2024, bhw.hrsa.gov/sites/default/files/bureau-healthworkforce/data-research/physicians-projections-factsheet.pdf.

7. GlobalData PLC. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036, Association of American Medical Colleges, Mar. 2024, http://www.aamc.org/media/75236/download.

8. GlobalData PLC. The Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand: Projections From 2021 to 2036, Association of American Medical Colleges, Mar. 2024, http://www.aamc.org/media/75236/download.

9. Berg, Sara. "The COVID-19 Emergency's over, but 1 in 2 Doctors Report Burnout." American Medical Association, 23 June 2023, https://www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/covid-19-emergency-s-over-1-2-doctors-report-burnout.

10. Scott, Bruce A. "More Medicare-Supported GME Slots Needed to Curb Doctor Shortages." American Medical Association, 4 Oct. 2024, www.ama-assn.org/about/leadership/more-medicare-supported-gme-slots-needed-curb-doctor-shortages.

11. National Center for Health Workforce Analysis. Health Workforce Projections, Bureau of Health Workforce, https://bhw.hrsa.gov/dataresearch/projecting-health-workforce-supply-demand. Accessed 20 Mar. 2025.

12. 12 Berg, Sara. "Physician Burnout Rate Drops below 50% for First Time in 4 Years." American Medical Association, 2 July 2024, http:// www.ama-assn.org/practice-management/physician-health/physician-burnout-rate-drops-below-50-first-time-4-years.

13. "Pulse on the Nation's Nurses Survey Series: COVID-19 Two-Year Impact Assessment Survey Younger Nurses Disproportionally Impacted by Pandemic Compared to Older Nurses; Intent to Leave and Staff Shortages Reach Critical Levels." Nursing World, American Nurses Foundation, Mar. 2022, http://www.nursingworld.org/practice-policy/work-environment/health-safety/disasterpreparedness/coronavirus/what-you-need-to-know/covid-19-impact-assessment-survey---the-second-year/contentassets/covid-19- two-year-impact-assessment-written-report-final.pdf.

14. "New Study: Behavioral Health Workforce Shortage Will Negatively Impact Society." National Council for Mental Wellbeing, 25 Apr. 2023, http://www.thenationalcouncil.org/news/help-wanted.

15 Kane, Leslie. "'I Cry but No One Cares': Physician Burnout & Depression Report 2023." Medscape, 27 Jan. 2023, http://www. medscape.com/slideshow/2023-lifestyle-burnout-6016058?faf=1.

16. Landers, Susan. "Burnout in Healthcare Workers: A Growing Crisis and How to Address It." Managing Medical Workplace Stress: Burnout in Healthcare Workers, Sept. 2024, susanlandersmd.com/managing-stress-in-medicine-burnout-in-healthcare-workers.

17. Han, Shasha, et al. "Estimating the Attributable Cost of Physician Burnout in the United States." Annals of Internal Medicine, U.S. National Library of Medicine, 4 June 2019, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/31132791/.

18. Hodkinson, Alexander, et al. "Associations of Physician Burnout with Career Engagement and Quality of Patient Care: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis." BMJ (Clinical Research Ed.), U.S. National Library of Medicine, 14 Sept. 2022, pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih. gov/36104064/.

19. Newitt, Patsy. "Physicians per Capita in All 50 States." Becker's ASC Review, 1 Nov. 2023, http://www.beckersasc.com/asc-news/ physicians-per-capita-in-all-50-states/?oly_enc_id=8907D8369567D7C.

20. Health Care Workforce: Key Issues, Challenges, and the Path Forward, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Oct. 2024, aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ documents/82c3ee75ef9c2a49fa6304b3812a4855/aspe-workforce.pdf.

21. Health Care Workforce: Key Issues, Challenges, and the Path Forward, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation, Oct. 2024, aspe.hhs.gov/sites/default/files/ documents/82c3ee75ef9c2a49fa6304b3812a4855/aspe-workforce.pdf.

22. Verma, Seema. "Early Impact of CMS Expansion of Medicare Telehealth During COVID-19." Health Affairs, 15 July 2020, http://www. healthaffairs.org/content/forefront/early-impact-cms-expansion-medicare-telehealth-during-covid-19.

23. The Evolution of Telehealth during the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Multiyear Retrospective of FAIR Health's Monthly Telehealth Regional Tracker, FAIR Health, 14 June 2022, s3.amazonaws.com/media2.fairhealth.org/brief/asset/The Evolution of Telehealth during the COVID-19 Pandemic-A FAIR Health Brief.pdf.

24. Monthly Telehealth Regional Tracker, FAIR Health, http://www.fairhealth.org/fh-trackers/telehealth. Accessed Feb. 2025.

25. What is Telehealth? Health Resources & Services Administration, Mar. 2022, https://www.hrsa.gov/telehealth/what-is-telehealth

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.