The Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council has issued a far-reaching proposed rule that requires significant greenhouse gas reporting and emission reduction obligations for federal contractors.

TAKEAWAYS

On December 6, 2022, Pillsbury issued a client alert to notify government contractors that the Federal Acquisition Regulatory Council (FAR Council) recently issued a proposed rule that would require most federal contractors to make disclosures and representations regarding their greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions and for certain major contractors to also set science-based targets to reduce those emissions. Given the extensive scope of this proposed rule, our first client alert focused on outlining the identification and reporting requirements of GHG emissions that would be imposed upon government contractors. This client alert provides additional information regarding the nature of Scopes 1, 2, and 3 GHG emission categories, as well as some of the complexities associated with the reduction of GHG emissions in accordance with "science-based targets."

In the proposed regulation, the FAR Council has chosen to require government contractors to identify and report the three broad categories—or "scopes"—of GHGs recognized by the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which is currently the most widely-accepted GHG accounting standard in the world. These scopes are:

- Scope 1 Emissions—Direct GHG emissions from sources that the reporting organization directly owns or controls, such as manufacturing process emissions, and fuel combustion from furnaces, boilers, and organization-owned or controlled vehicles.

- Scope 2 Emissions—Indirect GHG emissions from the facilities and sources generating the electricity, heat, steam, and cooling used by the reporting organization.

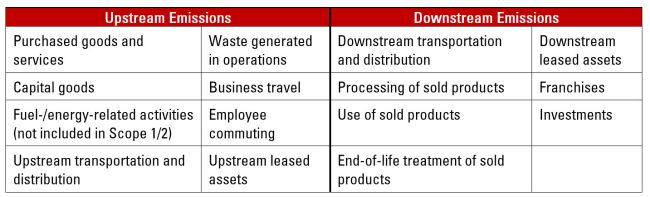

- Scope 3 Emissions—Other indirect emissions not covered in Scope 1 or 2 and not resulting from assets owned or controlled by the reporting organization, but that result at any point in the organization's upstream or downstream "value chain." This includes 15 categories of such wide-ranging activities as the organization's purchase of goods and services (and the emissions generated by those upstream suppliers), purchase and deployment of capital goods, employee commuting and business travel, the actual use of the organization's goods and services by downstream users, end-of-life disposal or recycling of any used products, and all fuel and energy activities related to the generation, development, transportation, and distribution of the organization's products and services.

As noted in the prior alert, virtually all federal contractors will be required to identify and report an inventory of its Scope 1 and Scope 2 GHG emissions, starting one year after a final FAR rule is issued. With limited exceptions, this requirement will apply to all government contractors who received $7.5 million or more in federal contract obligations in the prior fiscal year, regardless of whether the contractor is performing manufacturing, construction, or service contracts.

Government contractors who do not qualify as small business concerns and who received more than $50 million in federal contract obligations in the prior fiscal year are deemed to be "major contractors." A major contractor will be required to report an annual inventory of its Scope 1, Scope 2, and Scope 3 GHG emissions.

Beyond the contractor's direct emissions, which are categorized as Scope 1 emissions, the identification and reporting of other GHG emissions becomes much more complicated and difficult. Scope 2 and Scope 3 GHG emissions are generated further away—both by location and time—from the contractor's core business operations. Because Scope 2 and Scope 3 emissions are under the control of third parties that are often remote from the reporting contractor, there is significant uncertainty in accurately identifying and estimating these emissions. This remoteness also creates substantial burdens on the reporting contractor to gather and consolidate accurate emissions information from multiple third parties and increases the risk of double- or triple-counting GHG emissions from upstream and downstream entities, many of whom will have their own GHG reporting obligations. The tracing and untangling of these accounting issues will be challenging for many contractors. For example, the Scope 2 guidance documents issued by the GHG Protocol and EPA alone include almost 270 combined pages and require consideration of location-based vs. market-based calculation methods, requirements for contracts with energy providers, and specific accounting of "green power" within a mix of energy sources from the energy provider(s).

Perhaps the biggest challenge facing major contractors will be identification and reduction of Scope 3 GHG emissions. Managing the sheer range of identifying reportable Scope 3 GHG emissions has proven daunting even for the most sophisticated global corporations. Scope 3 guidance from the Greenhouse Gas Protocol requires calculation of GHG emissions from 15 different categories both up and down the value chain:

These Scope 3 emissions are, by definition, outside the contractor's direct control or oversight. This makes it difficult or impossible for contractors to control or reduce these emissions—particularly where the third parties are foreign entities or government entities. Indeed, many contractors will face uncertainties regarding how far back in the chain of global commerce they are required or able to track emissions. For example, is a federal contractor required to account for the GHG emissions associated with the mining of raw materials used in fabricating steel required for the organization's products, such as the emissions from machinery extracting and transporting the raw materials and from producing the steel? What about accounting for GHG emissions associated with producing the steel used to fabricate that mining machinery? Moreover, many entities up and down the value chain may already be reporting and taking measures to control GHG emissions under various regulatory schemes, and often will be in a better position than a federal contractor to effectively identify, estimate and reduce GHG emissions.

Yet, the proposed FAR Council rule would require major contractors to comply with these broad requirements or face the risk of a presumption of non-responsibility under FAR 9.1. A federal contractor would become ineligible for federal contracts if the contractor cannot prove that noncompliance was beyond its control and that it made "substantial efforts" to comply (and will comply within a year) with the rule. Moreover, as with any federal government contracting reporting and certification requirement, incorrect information could expose the contractor to potential civil or even criminal liability.

Compounding the inherent difficulty in assessing a major contractor's entire global GHG emissions will be the proposed FAR rule requirement that would impose a GHG reduction obligation on that contractor. The FAR rule would require these major contractors to develop "science-based targets" for reduction of their GHGs and have the targets validated by the Science-Based Targets Initiative (SBTi). These science-based targets must cover an implementation period of between five and 15 years. SBTi provides a tool for companies to set GHG reduction targets consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5 to 2 °C above pre-industrial levels.

Unfortunately, it will be impossible for contractors to know in advance what their GHG reduction requirements will be until a target is developed under the SBTi guidance and approved by SBTi. While the process does offer some flexibility for companies to customize a type of reduction target or target boundary appropriate to their sector or business, it will be a lengthy process for some facilities. Indeed, SBTi has not yet developed science-based targets for many industry sectors, including oil and gas, chemical manufacturing, steel, transportation, and aviation.

Moreover, SBTi guidance requires companies with at least 40 percent of their total GHG emissions in Scope 3 (probably most companies who will be reporting Scope 3) to set their GHG targets to achieve "ambitious" reductions of two-thirds of its Scope 3 emissions (citing various target examples ranging from 20% to 90% of a company's GHGs or GHG emissions intensity). The inherent difficulty in achieving such reductions among numerous remote or foreign third parties could make meeting these targets practically impossible for many contractors. Achieving such reductions is made even more difficult by SBTi's prohibition on a contractor's use of purchased GHG offsets toward reduction goals.

Ascertaining the full extent of reportable emissions, and in some cases setting enforceable goals to reduce those emissions to a yet-undefined goal, are just two of the more contentious issues surrounding GHG disclosure regulations. Addressing just these two issues will require contractors to review multiple U.S. and international sources of guidance, already totaling well over 1,000 pages of mandatory and optional standards.

The public comment period on the proposed FAR GHG Emission Rule is currently open through January 13, 2023. Pillsbury will continue monitoring this proposed rule and other proposed climate disclosure and reduction regulations, and we will provide updates as these regulatory processes develop.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.