Highlights

- The labor market has become more challenging for employers following COVID-19, and the need for well-trained, experienced employees far exceeds the supply.

- In addition to undermining investments in training and professional development, rampant departures are threatening the ability of employers to maintain confidential and proprietary information – including trade secrets.

- The legal landscape also is affecting the labor market, with enforcement of traditional non-compete agreements by employers becoming more difficult in recent years.

The current labor market is fraught with challenges for employers. In the wake of the COVID-19 market disruptions, the demand for employees, especially for experienced or highly trained employees, far exceeds the supply. Employee retention is a problem facing employers in all industries, from healthcare and life sciences to technology, manufacturing and hospitality. Rampant departures are undermining investments in training and professional development and threatening employers' ability to maintain confidential and proprietary information, including trade secrets.

In addition to these tough labor market conditions, the legal landscape affecting employers' abilities to retain employees has undergone significant changes. First, the enforcement of traditional non-compete agreements by employers has become more difficult over the past several years. As detailed further below, many states have outlawed or severely curtailed the use of non-compete agreements such that employers should tread carefully when seeking to retain employees by contracting in this way. Second, no-poach agreements, which have been used formally and informally for many years between employers to avoid "poaching" one another's talent, are facing private lawsuits by employees and aggressive government enforcement efforts. This Holland & Knight alert explores both issues and provides employers with guidance and best practices to navigate the increased challenges they present.

The Non-Compete Retreat

One of the most widely used methods for employers to retain employees, or at least limit their attrition, is through the use of non-compete provisions or agreements in employment contracts. In essence, a non-compete agreement prohibits employees from competing with their employer after the termination of the employment, usually within a certain time frame, industry and/or geographic area. Employers commonly use such terms to retain talent and reduce the impact that a departing employee may have on business operations. State and federal antitrust laws have traditionally deemed non-compete agreements permissible in an employment setting when reasonably tailored to address an employer's legitimate business need and if limited in geographic scope and duration. But in recent years, legislation has been enacted in several states to restrict or even prohibit non-compete agreements.

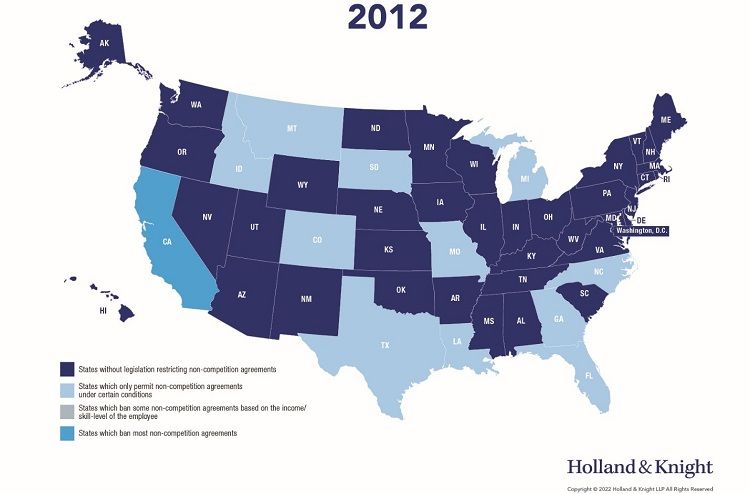

For example, in 2012, as reflected in the graphic below, a majority of states did not regulate the use of non-compete agreements at all:

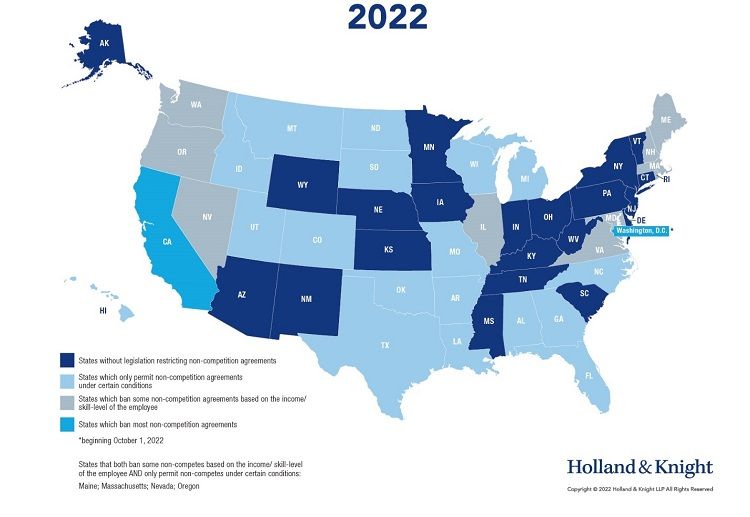

However, in the ensuing decade, policy perspectives began to shift against the use of non-competes. Between 2016 and 2021, 10 states enacted new legislation banning the use of non-compete agreements for low-wage or low-skilled workers: Illinois, Massachusetts, Maine, Maryland, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, Virginia, Washington, Oregon and Nevada. In addition, several jurisdictions have imposed widely varying employee notice requirements, including Oregon, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Maine, Washington, Virginia, Illinois and Washington, D.C. For example, Virginia requires employers to post a copy or an approved summary of the non-competition agreement laws. Some of these states also require employers to advise employees in writing to consult with an attorney before signing a non-compete agreement.

In 2021 alone, Colorado, Illinois, Nevada, Oregon and Washington, D.C., implemented new regulations limiting non-compete agreements, while numerous other states debated proposals. For example, on Jan. 11, 2021, District of Columbia Mayor Muriel Bowser signed the Ban on Non-Compete Agreements Amendment Act of 2020, which prohibits the use of most employee non-compete agreements, much like legislation in California, Montana, North Dakota and Oklahoma. That Act will take effect on Oct. 1, 2022. Strikingly, while the Act's ban on non-compete agreements applies only to employees in the District of Columbia, even employers who do not use non-compete agreements must provide notice of the new law.

As a result of these changes, the landscape of non-compete regulation looks markedly different in 2022 than it did in 2012. As reflected in the map below, now a majority of states either curtail or outright ban the use of non-compete agreements:

While the precise contours of these restrictions vary widely, the consequences of noncompliance can be significant. A Nevada statute amended in May 2021 allows employees to recover reasonable attorneys' fees if an employer tries to enforce an unlawful non-competition agreement. In Colorado, effective March 1, 2022, violation of that state's non-compete statute is a Class 2 misdemeanor.

Historically, regulation of employer-employee non-compete agreements has been a matter of state policy, but a July 9, 2021, Executive Order signed by President Joe Biden prompts the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to consider using its rulemaking authority to curtail or prohibit non-compete agreements. The Executive Order itself has no immediate legal effect, but if the FTC takes the cue, federal measures would impose the most pervasive limitations yet.

The Antitrust Division of the U.S. Department of Justice (DOJ) recently filed a "Statement of Interest" in a pending private lawsuit in Nevada state court seeking to invalidate non-compete clauses in employment contracts of physicians employed in a large anesthesia group.1 The DOJ Statement of Interest encourages the court to consider competition principles under federal antitrust laws in evaluating the reasonableness of the non-compete clauses under Nevada law. The DOJ argues that the non-compete agreement between the employer and its employees constitutes a horizontal territorial market allocation agreement which is per se unlawful under antitrust laws. Alternatively, the DOJ argues that the non-compete clauses should be invalidated under the "rule of reason," as they are not the least restrictive means of accomplishing any legitimate business justifications for the post-employment restrictions.

The No-Poach Assault

Another method commonly relied upon by organizations to retain employees is to agree with other employers, in a variety of different contexts, not to solicit or "poach" one another's employees. Numerous circumstances exist when a "no-poach" agreement might be useful to an employer, including pursuit of a joint venture, during the course of a services agreement or the sale of a division within a business, among others. Although no-poach agreements are also fairly commonplace, these arrangements have become increasingly perilous for employers due to a concomitant increase in antitrust scrutiny.

Generally speaking, antitrust laws prohibit agreements between competitors that unreasonably restrain trade. Courts evaluating antitrust claims under Section 1 of the Sherman Act consider either whether the agreement is anticompetitive on its face (i.e., per se illegal) or by balancing the pro-competitive benefits against the anticompetitive harms (what is known as the "rule of reason"). A horizontal restraint is naked and thus analyzed under the per se standard for a violation of antitrust law, if it has no purpose except stifling of competition. Usually, the rule of reason analysis applies where an agreement is ancillary to legitimate collaboration between competitors and presents pro-competitive benefits or justifications. In the past, federal antitrust agencies challenged no-poach agreements civilly2 and sparingly.

However, beginning in 2016, the FTC and DOJ jointly announced a new policy position to challenge naked no-poach agreements criminally.3 Since then, the DOJ has engaged in extensive efforts to transform that policy position into law. For example, in 2019, in a trio of civil cases raising the issue of whether no-poach agreements between franchisors and franchisees violate Section 1 of the Sherman Act, the DOJ filed a Statement of Interest arguing that, while most franchisor-franchisee restraints are subject to the rule of reason, naked no-poach agreements between competitors are per se illegal under antitrust laws. The DOJ has also advocated for this position in a statement of interest in a case involving a no-poach agreement between a parent corporation and its subsidiaries.

Later in 2020, the DOJ reiterated its position in an amicus brief in the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit in a case involving a no-poach agreement between a subcontractor and a subcontractee who both operate to provide travel nurses and therefore are competitors for employees. See Aya Healthcare Services, Inc. v. AMN Healthcare, Inc., Case No. 20-55679, Dkt. Entry 14 (9th Cir., Nov. 19, 2020). In its amicus, the DOJ insisted the no-poach agreement in question was a horizontal labor-market allocation between competitors rather than a vertical one between companies at different stages of the supply chain. The DOJ also used the amicus as an opportunity to defend its well-documented position that naked no-poach agreements between competitors are per se unlawful under the Sherman Act, as well as to clarify that an otherwise per se illegal no-poach agreement will be permitted only if it is an ancillary restraint – that is, the agreement is reasonably necessary to achieve a separate, legitimate collaboration.4

More recently, the DOJ made an aggressive attempt to implement its policy position by bringing two separate criminal prosecutions against two healthcare companies for the use of no-poach agreements. Although one of the prosecutions resulted in an acquittal for both the healthcare company and its former CEO, the case proceeded past a motion to dismiss by the defendants. The DOJ remains adamant that surviving a motion to dismiss in that case effectively established the principle that harm to employees is also antitrust harm (i.e., harm to competition). As a result, there is no realistic expectation that the DOJ will walk back its position on the potential criminality of no-poach agreements.5 To the contrary, the DOJ is expected to continue to pursue its position aggressively in the months and years to come.6

Of course, the DOJ's intention to attack naked no-poach agreements is not the only threat employers must consider. The FTC, which shares antitrust enforcement with the DOJ in the civil context, has similarly voiced concerns regarding anticompetitive conduct in the labor markets that could involve a focus on no-poach agreements. Similarly, state attorneys general have challenged no-poach agreements in some instances pursuant to state antitrust laws.7 In other cases, the challenges are based on other state laws, including those governing restrictive covenants.8 No-poach agreements are also subject to challenges by private plaintiffs. The increase in government prosecutions is expected to encourage more private plaintiff litigation as well. In light of the foregoing, it cannot be overstated that the risk profile of no-poach agreements today is significantly different than it was just a few years ago.

The Best Practices Armament for Employers

In today's labor market, employers have their work cut out for them. In addition to the normal challenges to recruiting and retaining talent, employers must be mindful of the challenges the recent changes in the non-compete and no-poach legal landscape present. What's an employer to do?

When preparing an employment contract with a non-compete provision or a freestanding non-compete agreement, an employer should consider the following:

- What are the specific business needs requiring the use of a non-compete agreement? If certain types of employees or the confidentiality of certain information are the concerns, then employers should consider the specific context when framing the terms of the non-compete to address those concerns.

- Is the non-compete agreement narrowly tailored in duration and geographic scope?

- What training, exposure to patients, clients or customers or other business strategies and techniques did the employer provide that would allow the employee to engage in unfair competition with the former employee?

- What is the likely impact on competition in the overall market that will result from enforcement of the non-compete? Does the employee have special skills that are not otherwise reasonably available in the geographic area covered by the non-compete?

Similarly, what is clear from the above is that "naked" no-poach arrangements are extremely problematic and, to the extent possible, should be avoided. Although the DOJ has largely been unsuccessful in securing jury verdicts in its no-poach prosecutions, the risk of criminal liability is worth consideration of a revised approach.

By contrast, for no-poach agreements that are ancillary to a legitimate business purpose, the employer entity should consider the following:

- What is the purpose of the arrangement, and is the no-poach provision ancillary and subordinate to a legitimate pro-competitive agreement?

- Consider the pro-competitive purpose of the agreement (e.g., protecting confidential or proprietary information) and whether the agreement is reasonably necessary and narrowly tailored to achieve that objective. What is the relationship between the parties to the no-poach agreement? Do the parties interact or collaborate in a way that makes assurances against hiring each other's employees necessary to promote a worry-free working environment during the period of the parties' relationship?

- What is the scope of the no-poach provision or agreement? Answering this question should involve consideration of how many employees are covered by the no-poach agreement, including their specific function and their access to information relating to the other party to the agreement, the duration of the agreement, the geographic scope and, ultimately, the effect of the agreement (i.e., will the agreement limit the employees' ability to change jobs readily within their chosen field?). These components are essential to the practical implementation of a legal no-poach agreement.

- Consider employee consent: Are the employees aware of the no-poach agreement, and have they consented to it?

More broadly, employers should consider implementing or revising their antitrust compliance programs to address the current legal landscape detailed above. In particular, no-poach agreements may be implemented by managers who are unfamiliar with antitrust constraints. Thus, robust training should be considered to ensure such agreements do not create unnecessary antitrust risk.

Footnotes

1. Beck v. Pickert Medical Group, Case No. CV21-02092 (Washoe County, Nevada, Feb. 25, 2022).

2. See, e.g., In re High-Tech Emp. Antitrust Litig., 2011 WL 11683784 (N.D. Cal. Sept. 13, 2011).

3. See FTC Press Release, "FTC and DOJ Release Guidance for Human Resource Professionals on How Antitrust Law Applies to Employee Hiring and Compensation" (Oct. 20, 2016).

4. This "reasonable necessity" analysis would require a court to assess the pro-competitive benefit of a collaboration and whether it "can be achieved through means significantly less restrictive of competition than the challenged restraint," which in turn requires considering the scope and duration of the restraint. Although the Ninth Circuit upheld the "no-poach" agreement and rejected application of the "reasonable necessity" analysis, that analysis should nevertheless inform, to a degree, how entities construct these types of arrangements.

5. The Surgical Care Affiliates case remains pending with trial set for January 2023.

6. Earlier this year, a large manufacturer of military and aerospace products revealed that it received a grand jury subpoena as part of a DOJ criminal investigation into alleged agreements to limit hiring between the manufacturer's jet-engine unit and some of its suppliers.

7. The Illinois Attorney General recently filed a complaint against six temporary staffing agencies to enjoin and impose civil penalties for an alleged illegal no-poach agreement that may have suppressed competition for temporary workers (State of Illinois v. Alternative Staffing, Inc., et al., May 26, 2022).

8. Pittsburgh Logistics Sys., Inc. v. Beemac Trucking, LLC, 249 A.3d 918 (Pa. 2021).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.