- within Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

- within Law Practice Management topic(s)

INTRODUCTION

In a landmark ruling on 28 June 2024, the US Supreme Court expressly overruled the 40-yearold Chevron doctrine with its decision in Loper Bright Enterprises v. Raimondo, 1 eliminating the requirement that courts defer to federal agencies' interpretations of ambiguous statutes.

Congress cannot implicitly delegate authority through ambiguous terms, agencies no longer have a thumb on the scale when construing unclear statutes, and the courts have reasserted their role as the ultimate arbiter of what federal laws mean. The resulting effects are far-reaching. The Loper Bright decision affects every industry that is regulated by US federal agencies, and it is expected to usher in more frequent judicial challenges to agency rules, greater scrutiny of agency actions, and a different approach to lawmaking by Congress.

To help our clients understand, anticipate, and navigate the full impact of the Supreme Court's decision, we have developed The Post-Chevron Toolkit: A New Era for Regulatory Review (Toolkit). This Toolkit is designed to be a basic primer on the ramifications of Loper Bright on the regulated community. While this Toolkit is not meant to be a definitive catalog of every possible implication of the Supreme Court's decision, we have endeavored to highlight the core regulatory issues faced by our clients and the industries that we serve.

Inside this Toolkit, you will find:

- A primer on the "administrative state" and how Loper Bright fits into it.

- A one-pager on the Loper Bright decision and what it means.

- Frequently asked questions on what has (and has not) changed because of Loper Bright.

- A step-by-step checklist to the questions you should now ask when reviewing regulations.

- A refresher on statutory construction in the post-Loper Bright era.

- A glossary of frequently used terms and phrases.

We hope you find this Toolkit useful and always welcome your feedback

JUDICIAL REVIEW OF THE ADMINISTRATIVE STATE

The Administrative State

The combination of federal agency overreach and congressional inaction have created a controversial dynamic in the current landscape of administrative law. In short, as Congress became less involved with detailed rules and regulations, administrative agencies picked up the mantle. The Supreme Court is now responding to that dynamic by attempting to reinforce the powers of each branch of government and limit agency actions that wade too far into lawmaking territory. Over the years, the Supreme Court has taken steps to limit the power of the so-called "administrative state"—i.e., the large array of administrative agencies that wield substantial authority over the daily activities of individuals and businesses. The Supreme Court has done so through the judicial review of agency actions

Judicial Review of Agency Action

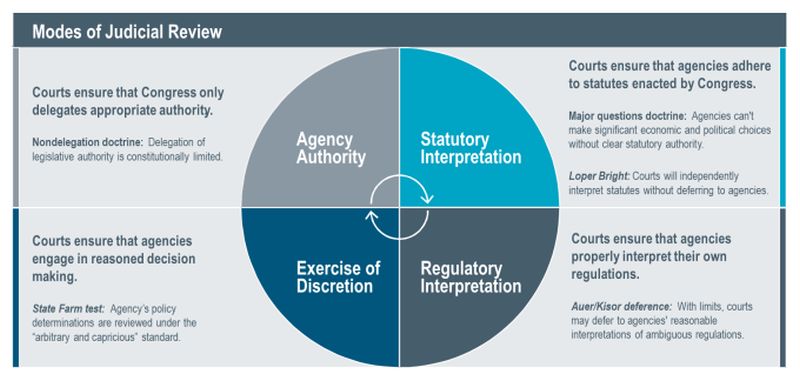

Typically, federal courts review agency actions when they are enforced against, or challenged by, individuals or entities. In turn, there are different categories of challenges that courts review, including claims that: (1) Congress improperly delegated regulatory authority to the agency to begin with; (2) the agency deviated from the authority that Congress gave it; (3) the agency deviated from its own regulations; and (4) the agency improperly executed lawfully obtained authority by making a policy decision that is arbitrary and capricious. These modes of judicial review are depicted below:

For more information on the caselaw supporting these different modes of judicial review, see the "QUICK GUIDE: AGENCY DEFERENCE CASELAW AND THE EFFECT OF LOPER BRIGHT " chart beginning on page 19.

Recently, with a conservative supermajority, the Supreme Court has issued several decisions—with Loper Bright at the forefront—that have significantly altered the balance of authority between the branches. As discussed in this Toolkit, the Loper Bright decision will impact how federal courts review agency interpretations of statutes. Depicted under the Statutory Interpretation quadrant above, the decision is primarily aimed at ensuring that agencies adhere to the relevant statutes and that the courts independently interpret the text of those statutes.

But the decision may have further effects. Loper Bright is potentially emblematic of how the Supreme Court will view its position with respect to all the modes of judicial review of agency decisions. With the Supreme Court more actively policing the boundaries of authority between the branches, it seems more likely than ever that the federal judiciary will continue placing limits on the administrative state.

AT A GLANCE: THE LOPER BRIGHT DECISION

"Chevron Is Overruled"

The Chevron doctrine, established by the Supreme Court in 1984, directed courts to defer to a federal agency's reasonable interpretation of an ambiguous statute that the agency administers.2 A cornerstone of modern administrative law, Chevron assumed that an ambiguous statute could have multiple meanings, and it gave agencies the power to choose among them. Loper Bright decisively overruled Chevron, signaling a fundamental shift in courts' oversight of federal agencies.

The Supreme Court's Holding

In Loper Bright, the Supreme Court held that the Administrative Procedure Act (APA) requires courts to exercise "independent judgment" in determining whether an agency's actions align with its statutory authority. In other words, courts must "independently" interpret the statute and effectuate the will of Congress. Going back to basics, courts must use the "traditional tools of statutory construction" to resolve statutory ambiguities and find the "single, best meaning" of the statute. In overturning Chevron, the Supreme Court returned to "the traditional understanding of the judicial function." Courts may still look to an agency's interpretation of a statute for guidance, particularly if it is long-standing or rests on "factual premises" within the agency's expertise. But courts will always have the final say about what the law means; the agencies will, at most, be given "respectful consideration" under Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 3 a pre-Chevron mode of analysis that left the ultimate interpretive authority with the courts.

Near-Term Impacts

Empowering Regulated Entities

The Loper Bright interpretative methodology levels the playing field, allowing regulated entities to offer interpretations of ambiguous statutes that may now compete equally against agency interpretations. It empowers regulated entities to challenge agency decisions with reasoned arguments.

More Precision Needed From Congress

Under Loper Bright, Congress still retains the ability to delegate authority to agencies, but it must do so expressly. Courts will no longer infer delegation from statutory silence or ambiguity, and they will "police" the outer boundaries of any express delegations to ensure that agencies remain within them. The Supreme Court's ruling thus demands a more precise approach by Congress and is likely to discourage broad, vague grants of authority to agencies.

Settled Expectations May Become Unsettled

Loper Bright allows courts to play a more active role in scrutinizing federal regulations. But despite overturning Chevron, the Supreme Court emphasized that the ruling does not automatically invalidate prior cases decided under the Chevron framework. The specific holdings of those cases remain valid under the principle of stare decisis. Stare decisis is not an insurmountable obstacle, but it creates an additional hurdle for challenging old statutory interpretations previously upheld by the courts.

FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS IN THE AFTERMATH OF LOPER BRIGHT

1. Does Loper Bright apply to state laws?

No. Loper Bright applies to the interpretation of federal law. The Chevron doctrine was a rule about how courts should interpret ambiguous federal statutes and the weight given to the federal agencies' interpretation of those statutes. Loper Bright overruled Chevron and held that courts must independently interpret federal laws without giving controlling weight to agency interpretations.

State courts have varying approaches to the deference given to state agencies interpreting state laws. States have developed their own approaches to the judicial deference owed to state administrative agencies that attempt to fill interpretive gaps in state law. A significant number of states have implemented rules of deference that parallel the Chevron rule of deference.4 It is possible, however, that some states may consider changing their approach after Loper Bright, particularly where the state judicial doctrines were intentionally patterned off Chevron. Pennsylvania is just one example, because its "notion of 'special deference' is taken from the United States Supreme Court's decision in Chevron[.]"5 A recent decision from the US District Court for the Western District of Pennsylvania suggested that, "[w]ith the recent demise of Chevron, . . . it seems likely that any remaining vestiges of Pennsylvania's 'special deference' doctrine will soon follow." 6

2. Does Loper Bright affect interpretations of federal regulations and executive orders?

Not directly. In Loper Bright, the Supreme Court was only asked to decide whether to overrule the Chevron doctrine, which was a rule about courts deferring to agency interpretations of federal statutes.

Auer deference was not overruled. Where an agency's own regulation is ambiguous, an agency may interpret the regulation through official policy guides, handbooks, memorandum, or other public documents. Under a doctrine called Auer (or Seminole Rock) deference, courts may defer to an agency's reasonable interpretation of its regulations, but only after the court first deploys all the traditional tools of statutory interpretation.7 While there is speculation about whether Loper Bright's reasoning might also be used to limit Auer deference,8 for now that doctrine of deference remains.

Deference to an agency's interpretation of an ambiguous executive order similarly remains, where warranted. The courts have previously deferred to an agency's expertise when interpreting an executive order that it is charged with administering.9 As with Auer deference, Loper Bright did not address this form of deference.

3. Will courts still defer to an agency's fact-finding and policy judgments?

The so-called arbitrary and capricious standard of review was not disturbed by Loper Bright. Courts generally defer to agency decisions that are based on factual and technical judgments, so long as there is a clear delegation from Congress to exercise that discretion. Under the long-standing arbitrary and capricious standard of review, an agency's policy decisions will be upheld if they are "reasonable and reasonably explained." An agency's factual and discretionary determinations will be deemed "arbitrary and capricious" only if they: (1) rely on factors that Congress did not intend; (2) fail to consider an important aspect of the problem; and (3) offer an explanation that is implausible or contrary to the evidence.10

But courts may soon begin demanding more clarity from agencies when applying the arbitrary and capricious standard of review. While Loper Bright did not affect the measure of deference that courts give to agency fact-finding and policy judgments, there has been speculation that the Supreme Court is otherwise trending toward a more rigorous application of the arbitrary and capricious standard of review. For example, in a case decided the day before Loper Bright, the Supreme Court found that an agency's failure to respond to a significant comment would make the agency's decision arbitrary and capricious—a ruling that drew sharp criticism from Justice Amy Coney Barrett and others on the Supreme Court.11

To view the full article, click here.

Footnotes

1. Loper Bright Enters. v. Raimondo, 144 S. Ct. 2244 (2024).

2. Chevron, U.S.A., Inc. v. Nat. Res. Def. Council, Inc., 467 U.S. 837 (1984), overruled by Loper Bright, 144 S. Ct. 2244.

3. Skidmore v. Swift & Co., 323 U.S. 134 (1944).

4. See Martha Kinsella & Benjamin Lerude, Judicial Deference to Agency Expertise in the States, STATE CT. REP. (Oct. 26, 2023), https://statecourtreport.org/our-work/analysis-opinion/judicial-deference-agency-expertise-states (providing overview of deference regimes in all 50 states, and noting that the judiciaries of 25 states provide robust deference to agencies' interpretation of state statutes).

5. McGuire v. Nationwide Affinity Ins. Co. of Am., 2:23-CV-1347 WL 4150098 at n.9 (W.D. Pa. Sept. 11, 2024) (quoting Woodford v. Ins. Dep't, 663 Pa. 614, 243 A.3d 60 (2020) (Donohue, J., concurring)).

6. Id.

7. Auer v. Robbins, 519 U.S. 452 (1997). The Supreme Court more recently articulated limits to Auer deference in Kisor v. Wilkie, 588 U.S. 558 (2019).

8. United States v. Boler, No. 23-4352, 2024 WL 3908554, at *3 (4th Cir. Aug. 23, 2024) (noting that the Supreme Court's recent ruling in Loper Bright "calls into question the viability of Auer deference").

9. See Udall v. Tallman, 380 U.S. 1, 4 (1965) (holding that courts must respect an agency's "reasonable interpretation" of an executive order and citing Seminole Rock); see also Kester v. Campbell, 652 F.2d 13, 15 (9th Cir. 1981).

10. Motor Vehicle Mfrs. Ass'n v. State Farm Mut. Auto. Ins. Co., 463 U.S. 29 (1983).

11. Ohio v. EPA, 603 U.S. __ (2024).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.