Perhaps you remember in 2019 when three Art Basel afficionados purchased a banana duct-taped to a wall for $120,000? Visual and conceptual artist Joe Morford does. And in 2020, he sued duct-taped banana creator and Italian artist, Maurizio Cattelan, for copyright infringement. Morford argued he had already taped a banana to a wall in his piece Banana and Orange 18 years before Cattelan displayed his banana-on-a-wall piece, Comedian, at Art Basel. The U.S. District Court for the Southern District of Florida, likely finding the whole dispute bananas, issued an order on cross-motions for summary judgment holding that Cattelan's fruit art did not infringe Morford's.

In its analysis, the court made dispositive findings that (1) Morford failed to demonstrate that Cattelan had access to Banana and Orange and (2) Cattelan successfully showed he had independently created Comedian. The court additionally applied the abstraction-filtration-comparison test to undisputed facts that showed Comedian was not substantially similar to copyrightable expressions in Banana and Orange.

I. Background

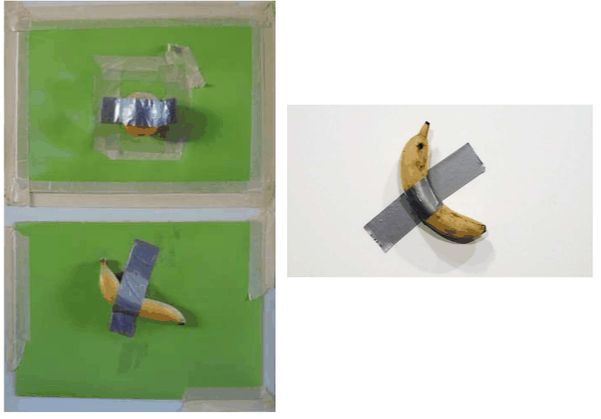

Morford developed Banana and Orange in California in 2001. Banana and Orange is a 3-D wall sculpture depicting a plastic orange affixed to a green panel using a single strip of plain gray duct tape placed horizontally over the orange. Below the orange is a plastic banana affixed to the wall with its stem pointing upward and to the left, also with a single strip of plain gray duct tape placed perpendicular to it creating an "X"-shape. The green panels are taped to a vertical surface using masking tape. An image of Banana and Orange from the opinion is depicted above and on the left. The work has been publicly available online in one video on YouTube since July 18, 2008; one post on Facebook since July 23, 2015; and one blog on Blogspot since July 2, 2016.

Years later in September 2019, Italian artist Cattelan conceived Comedian—a piece meant to be "simple," "banal," and to reflect "absurdity"—in response to a request he received to present a work at Art Basel. Cattelan drew inspiration from a previous work he made for New York Magazine in 2018 where he depicted a banana hanging from a billboard with red duct-tape. In developing Comedian, Cattelan remotely instructed employees in Italy to experiment with different heights and angles but did not test alternative methods of affixing tape to the banana other than perpendicularly in an "X"-shape. Comedian depicts an actual banana duct-taped to a wall at a specific height and at an angle such that the stem points slightly to the right. An image of Comedian from the opinion is depicted above and on the left.

In 2020, Morford filed an action for copyright infringement against Cattelan. Morford's copyright infringement claim survived a motion to dismiss after the court found "it could not resolve the alleged similarities or dissimilarities as a purely legal matter based only on pictures." But 11 months later, the court granted Cattelan's motion for summary judgment on the infringement claim and denied Cattelan's cross-motion on the same.

II. Analysis

To prevail on a motion for summary judgment, plaintiff Morford was required to show that there were no genuine issues of material fact as to whether (1) he owned a valid copyright and (2) Comedian copied Banana and Orange's protected, original expressions. Morford satisfied the first step (i.e., established ownership) by proving that he owned a valid copyright in Banana and Orange. But he failed to meet requirements under Step 2 to show that Comedian copied Banana and Orange by neither demonstrating (1) that Cattelan "actually used" Banana and Orange in Comedian nor (2) that the allegedly copied elements were "protected expression." Further, the court held that even if copying existed, Morford failed to rebut Cattelan's evidence that he independently created Comedian, which constituted a complete defense to infringement.

A. Morford Failed to Show Cattelan had Access to Banana and Orange

To prove Comedian copied constituent elements of Banana and Orange, Morford needed to show "factual copying" by "demonstrating that the defendant had access to the copyrighted work and that there were probative similarities" between the two works. Morford failed to meet the Eleventh Circuit's access standard, which required proof that Cattelan had a "reasonable opportunity to view" Banana and Orange.

Morford argued Cattelan had access to Banana and Orange because it had been "posted on the internet for several years" and "'verifiably viewed worldwide over a span of approximately 10 years prior to the appearance of [the] [D]efendant's piece." (Modifications in original.) However, the court found that "mere availability, and therefore the possibility of access, is not sufficient to prove access." Specifically, "[a] plaintiff cannot prove access only by demonstrating that a work has been disseminated in places or setting where the defendant may have come across it." Instead, Morford needed to show a nexus between the plaintiff and defendant.

Morford's evidence of availability on the internet failed to show a "reasonable opportunity for Cattelan to have viewed Banana and Orange" because Banana and Orange never "enjoyed any particular or meaningful level of popularity" and, to the contrary, evidence showed that Morford's piece was an "obscure work with very limited publication or popularity." Moreover, Morford was unable to demonstrate any nexus between himself and Cattelan. The only record evidence on this point was a declaration introduced by Cattelan that stated Cattelan had never heard of Morford.

Lack of access is dispositive and so the court could have concluded its analysis there. Nevertheless, the court assessed the works' similarities.

B. Comedian's and Banana and Orange's Similarities Are Unprotected

To ascertain similarity between the two works, the court applied the Abstraction-Filtration-Comparison Test. The test comprises three steps.

First, the court abstracts "the allegedly infringed program into its constituent structural parts." The purpose is to separate a work's copyrightable expressions from its uncopyrightable ideas. To do so, the court dissects "the allegedly copied work's structure and isolate[s] each level of abstraction contained within it." The purpose is to stop when the abstraction becomes so broad it is "no longer protected" because it would extend beyond expression to ideas.

Next, the filtration step "sifts out all nonprotectible material" from the abstracted parts. The merger doctrine teaches expressions are unprotectable "where there is only one or so few ways of expressing an idea that protection of the expression would effectively accord protection to the idea itself." For example, the court noted that there are few ways to express that something is prohibited and therefore a circle with a diagonal line crossed through it is an unprotectable expression. In other words, the expression merges with the idea. The filtration step may find abstracted parts to merge and sift them out of consideration for copying.

Finally, the test requires a court "compare any remaining kernels of creative expression with the allegedly infringing [work] to determine if there is in fact substantial similarity."

i. The Court Abstracts Banana and Orange into 14 Elements

The court abstracted Banana and Orange into the following parts:

- Two rectangular green panels

- each attached to a vertical wall

- by masking tape

- stacked on top of each other

- with a gap between each

- Roughly centered on each green panel is

- an orange on the top panel

- surrounded by masking tape

- a piece of silver duct tape crosses the orange horizontally

- a banana on the lower panel

- at a slight angle

- with the stalk on the left side pointing up

- fixed to the panel

- with a piece of silver duct tape running vertically at a slight angle, left to right

- an orange on the top panel

ii. Filtering Expressions of "A Banana with a Piece of Silver Duct Tape" That Merge with the Idea

Cattelan argued the "concept of taping a banana to a wall" was "one in the same" with the expression and urged the court to filter out this abstracted expression as unprotectable under the merger doctrine. Morford argued that "the method both artists chose—the banana and the duct tape placed at an essentially perpendicular angle, with a single piece of tape crossing the banana, and the two objects forming an 'X'—is a 'creative choice' that can be copied."

The court found the expression of "a banana fixed to the panel with a piece of silver duct tape running vertically at a slight angle, left to right" merged with the idea of "taping a banana to a wall." The court found that the X-shape configuration of tape and banana was "the obvious choice." Any other configuration such as placing the tape parallel (i.e., over the banana) or using several strips of tape, the court stated, would unnecessarily cover or obscure the banana. The court found that an artist is thus "left with 'only a few ways of visually presenting the idea"—all of which involve a piece of tape crossing the banana at some non-parallel angle." Because there was only one way to express the idea, the merger doctrine applied.

After filtering out "banana [that] appears to be fixed to the panel with a piece of silver duct tape running vertically at a slight angle, left to right," the court found the protectible elements of Banana and Orange that Comedian could legally copy to comprise green panels, masking tape as borders, a centered orange on top and banana on bottom, and the banana's placement at a slight angle.

iii. On Comparison, Comedian and Banana and Orange are Dissimilar

To compare which constituent parts of Comedian and Banana and Orange were similar, the court grouped abstracted features into four elements: background, border, placement, and angle.

The first three were facially dissimilar. Banana and Orange used a green background separate from the wall, where Comedian used any wall as the background. Banana and Orange used a plain masking-tape border, where Comedian used no border. Banana and Orange placed a banana roughly centered in a panel below an orange, where Comedian placed a banana at a specified height from the floor.

Only the bananas' angles were materially contested as similar. But the court found that the banana's stalk simply being on the left-hand side was too insignificant and insufficient to find that the copied elements were "'protected expression' such that the appropriation [was] legally actionable." Morford also urged the court to find substantial similarity where "the bananas' angles are relatively similar." Rejecting this argument, the court found "this point works against him" because "there are only so many angles at which a banana can be placed on a wall (360, to be precise)." By making "such a minute distinction" between angles, the court would "place a significant legal limit on the number of ways that a banana can be taped to a wall without copying another artist's work." The court reasoned that such a finding would be equivalent to finding that Morford could copyright the idea of duct-taping a banana to a wall, which the court "has already said it cannot do."

Accordingly, the court held that Comedian and Banana and Orange were not substantially similar and therefore Comedian had not copied Banana and Orange.

C. Independent Creation Doctrine Shields Cattelan from Liability

Even assuming Cattelan had accessed Banana and Orange and that Comedian bore substantial similarity to Banana and Orange, the court nonetheless held that Morford still failed to rebut evidence provided by Cattelan that he independently created Comedian. Cattelan defended the copying claims by submitting evidence, in the form of personal and employee affidavits, describing Comedian's creation process. First, Cattelan detailed how he adapted his New York Magazine piece to further demonstrate absurdity by charging $120,000 for a banana duct-taped to a wall. Second, Cattelan's employee Jacopo Zotti, submitted a declaration describing how Cattelan telephonically instructed him to adjust the banana's angle and height as well as the lengths of duct-tape until they met his exacting standards.

In contrast, Morford failed to submit record evidence that raised a genuine dispute of material fact regarding Cattelan's independent creation defense. Morford merely challenged Cattelan's declarations in its responsive briefing by arguing that the court could not "base independent creation on [Cattelan's] facts alone" and by making an unrelated statement that "Cattelan is willing to appropriate another artist's work." The court accordingly found that Cattelan was "the only party who has put forward any evidence addressing the defense of independent creation." Thus, even if Morford could prove that Cattelan copied Banana and Orange, "the independent creation doctrine would prevent his recovery."

The case is Morford v. Cattelan, Case No. 1:21-cv-20039-RNS (S.D. Fla. June 12, 2023).

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.