- within Finance and Banking topic(s)

- in Africa

It's Black History Month again, so it's a good time to revisit the issue of representations in advertising. Four years ago, to mark Black History Month 2020, Brinsley wrote an article addressing the representation of race in advertising over the preceding 20 years, specifically touching on how major brands navigate - or fail to navigate - depictions of race without perpetuating harmful stereotypes. Fast forward to today, and the controversy surrounding Heinz's latest campaign for its family-sized pasta sauce raises a troubling question: Has anything really changed, even in the last four years?

The Heinz ad, which appeared on the London Underground, featured an interracial couple at a wedding table, promoting their product in what was meant to be a celebration of modern families. Instead, it sparked outrage for its "erasure" of Black fathers, leaving many, including public figures, wondering how such a glaring oversight made it through the approval process.

Perhaps even more troubling than the wedding ad was another advert that Heinz recently published in the United States to coincide with the release of the new movie, Joker: Folie à Deux.

This image is even more shocking than the wedding advert. Many commentators have pointed out the connection with blackface, minstrel shows and clowns. Yes, there may be a connection with The Joker, but that does not exclude these other references, which are very troubling and immediately obvious, at least to to any Black person.

It's also stark reminder that, despite years of progress - or the promise of it - advertising still struggles to tell diverse stories without missteps. As I reflect on the current outcry and compare it to similar incidents in the past, it begs the question: Are we really learning from these moments, or are brands still walking the same tightrope, balancing visibility with responsibility?

As we delve into the broader landscape of race and racism in advertising, it's worth recalling Brinsley's sharp critique of the JD recruitment ad from 2021 ASA condemns recruitment ad as both racist and sexist., Brinsley Dresden (lewissilkin.com), which was rightly condemned by the Advertising Standards Authority for its use of blackface—a tactic so obviously out of place in modern advertising. The ad was a glaring reminder of how deeply racial insensitivity can be entrenched in the industry, even in the context of recruiting young talent. It's astonishing that such an oversight could be made, yet it highlighted a recurring issue: the lack of diverse perspectives in the ad creation process.

Not long before that, we witnessed the NHS COVID ad controversy. Unlike JD's ad, which faced a clear judgment, the NHS ad avoided any censure by the ASA, despite apparently receiving at least one complainant who reached out to Brinsley after he'd submitted his complaint. We don't know why the ASA declined to investigate, so I am left wondering how is it that such a significant campaign, funded by public money, could touch the raw nerve of racial insensitivity without being challenged?

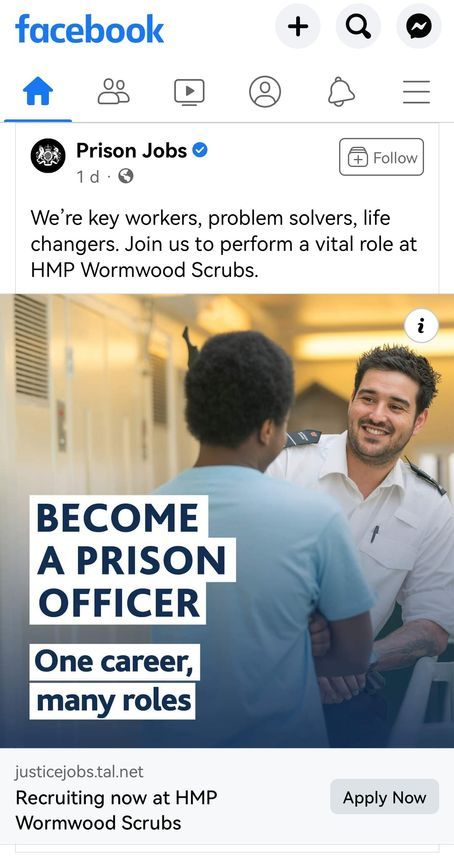

Could this delay signify an even deeper institutional avoidance when it comes to acknowledging these critical missteps? Not necessarily, because when the Ministry of Justice published this advert to promote jobs in the Prison Service, the ASA did investigate the complaints that it received and found the MoJ to be in breach of the CAP Code, as reported at the time by our colleague, Ardie Yilinkou. After Ardie published his article the ASA completed an Independent Review of their adjudication, and although they changed the wording of the decision, they maintained their position that the complaint should be upheld.

What both these cases share is an apparent failure to ask a simple, but vital, question: What message are we sending with this ad? And perhaps more importantly, who is being asked this question? It seems clear that the right people - the ones directly affected by these representations, Black communities - are often left out of the discussion. Until this changes, we risk continuing to see ads that perpetuate the very stereotypes brands claim to be fighting against.

Another example since Brinsley wrote his article in 2020 and which echoes this issue comes from Vic Smith Bedding's ad, which featured a deeply insensitive portrayal that was swiftly condemned by the ASA. The ad's blatant disregard for the feelings of marginalised communities shows that, even today, the industry can fail to meet the most basic standards of respect and inclusivity.

But perhaps there is hope for progress. The ASA has recently published new guidelines for Black History Month 2024, focusing on avoiding offensive depictions of race in ads. They aim to push brands to be more aware of racial sensitivities and guide them towards better representation.

Brinsley also tells me that Heinz have tried to be champions of diversity and inclusion in the past, producing the first TV commercial to feature a gay kiss between two men in 2008. Ultimately the advert was withdrawn following a backlash in the right wing media, which in turn provoked outrage among gay rights activists. Brinsley's concern is that if a brand that tries to achieve inclusivity and reflect diversity when creating their advertising faces severe reputational damage if they make a mis-step, will they simply decide to play it safe, and revert to the exclusive use of white, heterosexual nuclear families? There are plenty of reactionary people who would be only too pleased if that were the outcome.

However, this raises another question: Who will be in the rooms where these decisions are made? While the guidance is a step forward, if the same voices—those disconnected from the realities of the Black community—are the only ones heard, we might continue to see well-intentioned ads that miss the mark. The real challenge lies not only in creating the right rules but also in ensuring the right people are part of the conversation.

It's important to note that while these steps seem promising, only time will tell if they lead to genuine change. Will brands take this as an opportunity to embrace diversity authentically, or will they tread the line of performative representation? More crucially, will the voices that need to be amplified - the voices from the communities being depicted - finally be heard?

Let's hope that in the next four years, we won't be asking the same question again.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.