On 6 April 2016, the United Kingdom became the first EU and OECD country to enact legislation requiring every UK registered private company to create a register of "people with significant control", and to make that register available to the public.

The only departure from an indiscriminate publication policy in the legislation is a concession to individuals who can show to the satisfaction of the Registrar that to publish their personal particulars would put them or those that live with them at serious risk of violence or intimidation.

Who is a PSC?

The 5 conditions of PSC status (contained in paras 2-6 of schedule 1A of Companies Act 2006) are set out below for reference.

X is a person with significant control if:

- Condition 1: X holds, directly or indirectly more than 25% of the shares in UK Co.

- Condition 2: X holds, directly or indirectly, more than 25% of the voting rights in UK Co.

- Condition 3: X holds the right, directly or indirectly, to appoint or remove a majority of the board of directors of UK Co.

- Condition 4: X has the right to exercise, or actually exercises, significant influence or control over UK Co.

- Condition 5: the fifth condition is

that:

- the trustees of a trust or the members of a firm that, under the law by which it is governed, is not a legal person meet any of the specified conditions in relation to company Y , or would do so if they were individuals; and

- X has the right to exercise, or actually exercises, significant influence or control over the activities of that trust or firm.

1. The gov.uk electronic incorporation platform: a hole in the UK's regulatory fabric

The most challenging criticism of the legislation has centred around the reliability of information entered on company PSC registers by users of the UK government's electronic incorporation platform. This is in effect a gap in the UK's regulatory fabric. More than 40% of UK company formations are now processed through this medium, which is not subject to the UK's Money Laundering Regulations. The Registrar therefore does not undertake any verification of the identity of "persons with significant control" that are submitted on incorporation. Neither does the government's platform enquire into the personal and professional histories of PSCs. Of course, this is well beyond the scope of the Registrar's statutory duties.

The obvious concern is that criminals will gravitate to the UK registry's web-based incorporation platform and by-pass the regulated sector, in order to provide false PSC particulars to the PSC register. This concern has obvious validity. Another concern is that because such a significant amount of PSC data is provided to Companies House unmediated by regulated professionals and is unverified, the quality and usefulness of PSC information may be compromised. In this regard, Jordans Business Information Division identified approximately 169,000 UK companies disclosing 3 or fewer registered shareholders (therefore indicative that at least one of the shareholders should be a PSC), that had stated that there was no PSC. A random selection of 50 such companies (admittedly a very small sample) showed that 42 of these companies appeared to have filed unreliable PSC statements.

This analysis took place in January 2018. It is a matter of public record that Companies House is striving to improve the accuracy and reliability of PSC data held on the central register. Searchers are being encouraged to report PSC errors or inconsistencies they discover, and Companies House are contacting companies whose PSC information appears to be obviously incorrect.

2. The policy of public disclosure of PSCs

The publication of the PSC register on a Central Register accessible to all, is a controversial aspect of the legislation. Objections can be raised to public access to central registers of PSCs on principles that honest people have a right to privacy, and that such a regime is disproportionate.

Other EU Member States appear to be formulating legislation according to the MLD 4 which is more proportionate. Malta's legislation limits access to beneficial owner information to National Competent Authorities, Financial Intelligence Units, National Tax Authorities, and "subject persons" (i.e. persons requiring the information for anti-money laundering due diligence purposes). Any other person or organisation must apply in writing for permission to obtain beneficial owner information, demonstrating a legitimate interest.

It seems unlikely at present that a "non-subject" person would be granted access to beneficial owner information. It appears that other EU Member States are taking a broadly similar line to that of Malta.

This more measured and proportionate approach to central beneficial owner registers is consistent with an Opinion issued by the European Data Protection Supervisor on the revisions proposed to the 4th AML Directive. In his Opinion, issued on 2 February 2017, the Supervisor refers several times to the possible disproportionality of the 4th AML Directive's legislation: "As far as proportionality is concerned, in fact, the amendments depart from the risk-based approach adopted by the current version of the AML Directive... They also remove existing safeguards that would have granted a certain degree of proportionality, for example, in setting conditions for access to information... Last, and most importantly, the amendments significantly broaden access to beneficial ownership information by both competent authorities and the public, as a policy to facilitate and optimise enforcement of tax obligations. We see, in the way such solution is implemented, a lack of proportionality, with significant and unnecessary risks for the individual rights to privacy and data protection".

Member States have had to alter national legislation at the direction of the EU in the past under the general principle of proportionality, which is a strong feature of EU law. National legislation has been struck down or amended, not because the public policy aims behind such legislation were not justifiable, (e.g. to prevent tax evasion) but because the legislation went further than was necessary to achieve the policy. The UK's PSC regime is indiscriminate disclosure policy seems to fall into this category, and it is instructive to see other Member States putting more obvious limits on free public access.

3. UK branches of foreign companies

The legislation creating the PSC register does not apply to UK branches of foreign-registered companies. Concerns were raised at the consultation stage that this might lead to international investors forming foreign registered companies in preference to UK companies for UK business activity – an obvious "own goal" for the UK's company formation and administration industry and the UK economy. It now seems this trend may be exacerbated as other leading financial centres of the EU adopt a more measured approach to beneficial ownership disclosure, therefore distorting business decisions around company formation.

4. Can a company be a PSC? Non-UK companies and the golden rule

The "golden rule" of the UK's PSC legislation is that companies can only be registered on a PSC register if they are "relevant" i.e. subject to their own disclosure requirements. The most common example of a relevant legal entity is another UK company subject to the PSC regime.

At the time of writing, the only foreign-registered companies that can be registrable relevant legal entities are those whose shares are admitted to trading on EEA markets or specified non-EEA markets.

In due course it is possible that Regulations will be passed by the Secretary of State to qualify unlisted foreign companies registered in the other European Union and European Economic Area Member States as "relevant legal entities", because they are or will be subject to their own disclosure requirements as a result of the transposition of the Fourth EU Money Laundering Directive into their national laws.

Data analysis from Jordans Business Information Division suggests that at the beginning of 2018, approximately 4,500 UK companies had entered foreign – registered companies on their PSC registers. Many of these companies were registered in well-known offshore financial centres. It is unlikely that all or even a majority of these offshore companies' shares were admitted to trading on the appropriate regulated markets to be registrable. The uncertainty around these filings further undermines the reliability of the UK's central register, and the quality and reliability of its data.

5. Indirect ownership of shares or rights in conditions 1-3 of PSC

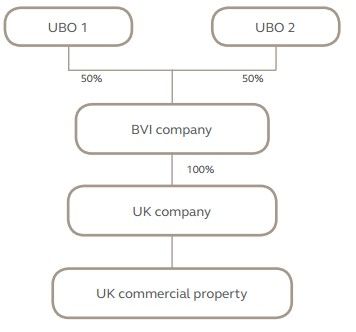

Where beneficial ownership of a UK company is indirect via offshore companies, anecdotal evidence suggests that interpretation and application of the PSC rules appears to be far from uniform. The following structure of ownership of a UK company will not be untypical where non-UK resident or non-UK domiciled beneficial owners are involved:

In this example, the use of a British Virgin Islands company provides significant protection from UK Inheritance Tax. Even if all the value of the BVI company shares derives from the UK commercial property, the UK IHT situs rules currently regard the shares as nonUK situated. If UBO 1 and UBO 2 are non-UK domiciled, then their BVI company shares are excluded property for UK IHT purposes. It is of the essence of this planning that the BVI company is not a mere nominee, and that instead UBO 1 and UBO 2 own the shares of the UK company indirectly through the BVI company. The question is whether such indirect ownership of the UK company shares makes UBO 1 and UBO 2 PSCs of the UK company.

Jordans have encountered various mistakes concerning UK companies with this sort of ownership structure.

- Assuming that UBO 1 and UBO 2 must be PSCs. The BVI company cannot be registered on the PSC register (it is not a relevant entity), and for the purposes of the UK's Money Laundering Regulations the two individuals are each beneficial owners of (indirectly) 50% of the UK company. So it is easy to see why UK company officers might assume UBO 1 and UBO 2 are also PSCs . But the PSC rules do not work in the same way as the AML rules. The PSC legislation requires indirect shareholders like UBO 1 and UBO 2 to possess "majority stakes" in offshore companies as defined in Paragraph 18 of Schedule 1A, Companies Act 2006 in order to be treated as controlling UK company shares or rights held by the BVI company. Where a BVI company or other non-UK registered company is "deadlocked" at shareholder level as in the example, or where the shareholdings in the offshore holding company are such that no-one has a majority stake, no beneficial owner should be registered as a PSC of the UK subsidiary company under conditions 1-3.

- Assuming that if UBO 1 and UBO 2 are related (e.g. by blood or marriage), then they are PSCs by virtue of entering into a "joint arrangement". This is incorrect. The PSC rules do not aggregate the shareholdings of related parties unless there is a plan or arrangement that two or more persons will exercise all or substantially all the rights conferred by their shares in a way that is pre-determined . Otherwise, there is no joint arrangement, and there should be no presumption that there is such an arrangement between related parties.

- Recording directors of a UK company as PSCs. This is incorrect. In the normal run of cases, a directorship is an "excepted role", and so does not create PSC status of itself.

- Assuming that any offshore holding company is the PSC. As already noted, there is evidence that as at January 2018 around 4,500 offshore companies had been registered as PSCs. To the extent that any of these entities are unlisted, then the UK's PSC regime is arguably being compromised. The golden rule is that offshore companies are not to be registered on a PSC register unless they are both relevant and registrable legal entities as described in section 4 of this article.

6. Condition 4: Having the right to exercise or actually exercising significant influence or control of the UK company

It was inevitable that such a broad-brush condition would lead to subjective judgement, and therefore no possibility of a uniform interpretation and approach.

De facto "significant influence or control" requires consideration of the mentality of both the de facto significant influencer, and the directors or shareholders it is claimed are being significantly influenced. X may think he is a PSC, but the directors may take little or no heed of his advice or instructions. Regulated directors will always take into account the requests of the beneficial ownership of a company, but in the final analysis their decisions will be significantly influenced by corporate governance theory, and regulatory issues.

The statutory guidance is reasonably clear that along a spectrum of significant influence or control which at the lowest end of the spectrum might be someone making requests or proposals for the board's independent consideration, to the opposite end of the spectrum someone who dictates to the directors what is to be done, the statutory guidance sees significant influence and control as located at the latter end of this spectrum. So, someone actually exercising control must "direct the activities of the company", according to the statutory guidance, and someone actually exercising significant influence must be able "to ensure that a company generally adopts the activities which they desire".

Provided the de jure directors of the UK company and the BVI company in the example in section 5 do not surrender their discretion, then the directors are the independent forum by which the wishes of the beneficial ownership become activities of the company. It does not then follow that the beneficial owners are PSCs under condition 4.

There is a lot of UK and Commonwealth case law involving "shadow directors", who controlled companies in conditions of secrecy, deliberately hiding behind de jure directors who abnegated their powers and duties of management and control. It is probably this sort of "eminence grise" that condition 4 is attempting to unmask, but these arrangements are rare, and the Companies House guidance sent to newly incorporated companies states condition 4 is likely to apply "only in limited circumstances" (see PSC/05/17/v.2.0).

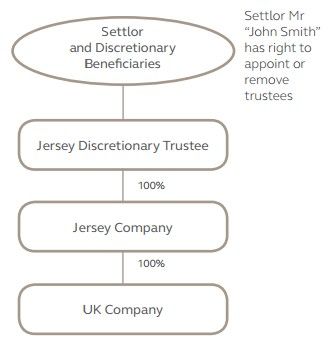

7. Trusts

Where a UK company's shares are owned directly or indirectly by a discretionary trust, the fifth condition of PSC status will be in point (para 6 , Schedule 1A CA 2006). Condition 5 states that "X" will be a PSC where:

"(a) ...the trustees of a trust that, under the law by which it is governed, is not a legal person meet any of the other specified conditions (in their capacity as such) in relation to "Y", or would do so if they were individuals AND

(b) "X" has the right to exercise, or actually exercises significant influence or control over the activities of that trust or firm".

A feature of the condition of PSC status in relation to trusts is that it has two limbs. The trustees must firstly be conducting trusteeship such that, were they not trustees but individuals, they would be PSCs, under one or more of conditions 1-4; and secondly an individual "X" has the right to exercise or actually exercises significant influence or control over the activities of the trust.

Some advisors have concluded that the trustees are not registrable under limb (a) of the test, but only individuals who have the right to exercise or actually exercise significant influence or control over the activities of the trust (i.e. "X" in limb (b) of the test). The prescribed narrative contained in Schedule 2 of the "Register of People with Significant Control Regulations 2016" seems to bear out this interpretation, but it is not free from doubt. Schedule 2 contains the prescribed narrative for use on the PSC register when any one of the 5 conditions of PSC status are met. The prescribed narrative for trust ownership is set out in Part 5 of Schedule 2, and refers throughout to the trustees as "the trustees of that trust". For example, the specimen narrative for the PSC register of the UK company shown in Diag 5 would be:

"Mr John Smith has the right to exercise or actually exercises significant influence or control over the activities of a trust; and the trustees of that trust (in their capacity as such) hold directly or indirectly 75% or more of the shares in the company".

" Mr John Smith has the right to exercise, or actually exercises , significant influence or control over the activities of a trust; and the trustees of that trust (in their capacity as such) hold, directly or indirectly, 75% or more of the voting rights in the company".

"Mr John Smith has the right to exercise ,or actually exercises, significant influence or control over the activities of a trust; and the trustees of that trust (in their capacity as such) hold the right, directly or indirectly, to appoint or remove a majority of the board of directors of the company".

The statutory guidance indicates that Mr John Smith is likely to be a PSC, or "X" in limb (b) of the PSC test for trusts, because of his right to remove trustees under the trust instrument.

The general guidance issued by the government says that the trustees` names must always be registered in the PSC register if they meet any of conditions 1-4 of PSC status, regardless of whether there is an individual conforming to "X" in condition 5(b). This is not what condition 5 says, but if the guidance is to be followed, it does not clarify if the trustee is to be entered in the PSC register if it is an offshore company i.e. an entity that is not a relevant entity, and therefore not registrable as a PSC under the primary legislation. It is possible that some of the offshore companies being reported on the Central Register as PSCs act as trustees of trusts, and have been registered pursuant to the ambiguous government guidance. But the guidance is in conflict with the golden rule referred to in section 4 above that only relevant entities subject to their own disclosure requirements are registrable on a PSC register. An offshore corporate trustee is unlikely ever to be a relevant entity.

Perhaps the most sensible approach whilst this ambiguity remains unresolved is to consider registering any trustees under conditions 1-4 only if they are individuals, or relevant legal entities (e.g. UK corporate trustees).

Offshore corporate trustees: are their majority stakeholders registrable?

If the application of the PSC rules to trusts does not reveal an individual or relevant entity amongst the parties to the trust, does one "drill through" the corporate trustee in search of a majority stakeholder? Arguably one would not, given that the trust relationship between settlor, trustee and the beneficiaries is such that a majority stakeholder of the corporate trustee has no indirect interest in the share ownership of the UK company. The argument against this view is that the wording of the test is very wide, and that it would be prudent to conduct a review of a corporate trustees` major participants, to see if any of them conform to the test of X in condition 5 (b).

Conclusion

This article has identified some of the problem areas of the UK's PSC legislation, which relate to its disproportionality; its inherent unreliability (evidenced in some of the PSC data published by Companies House); its liability to deter the use of UK companies in favour of more proportionate corporate regimes (e.g. Malta and other EU-registered companies, or offshore territories such as Jersey) thus distorting business decisions; the current gap in the UK's regulatory fabric referred to in section 1 of this article with the consequence that a lot of PSC information is unverified; the public access to the PSC register possibly contributing to deliberate obfuscation; the misconceptions in the interpretation of the legislation where there are offshore holding companies, or trusts in the ownership structure of a UK company; the highly subjective nature of PSC condition 4; and the interpretive difficulties of condition 5 of PSC status as it applies to trusts, with an apparent conflict between the statutory language of condition 5 of PSC status, and the government's guidance on that condition.

The UK PSC regime appears to be flawed and out of step with the more considered and balanced thinking now being applied to this subject by the UK's many competitors for international capital within the EU. An EU Directive (AMLD 5) proposes further measures to increase the transparency of companies registered in the EU and EEA. The amending Directive says that Member States should allow the general public access to the beneficial owner data of companies, held on a central register in each Member State. However, the Directive provides Member States with a certain amount of discretion as to the conditions that should be attached to access beneficial owner data. Where the party seeking access is not a competent authority or Financial Intelligence Unit, or a regulated service provider required to gather "customer due diligence" before providing services to the company, or one of its affiliates, it will have to demonstrate legitimate interest. Until the amending Directive is transposed into national legislation in each Member State, it is at the moment too early to say what, if any, restrictions will be imposed by national legislatures to the right of the general public to obtain information on the personal particulars of the beneficial owners of companies.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.