On 19 April 2023, the High Court held that Tesco's use of its Clubcard sign (shown below) constituted trademark infringement and passing off of Lidl's logo as it misled shoppers into thinking that products offered under the Clubcard scheme were being offered at the same or lower prices as those in Lidl.

Additionally, the Court held that Lidl's logo was copied during the design process, so Tesco was also liable for copyright infringement.

As a result, Tesco may now have to stop using the blue and yellow logo to promote its Clubcard loyalty scheme.

The key questions the Court had to consider in this case were:

- Did Tesco's 'Clubcard Prices' logo infringe on Lidl's brand logo, as both logos appeared as text in a yellow circle on a blue background?

- Are consumers reminded of Lidl when shopping at Tesco with their Clubcard?

- Was Lidl's trade mark of a yellow circle on a blue background (without the Lidl text) registered in bad faith?

The Dispute

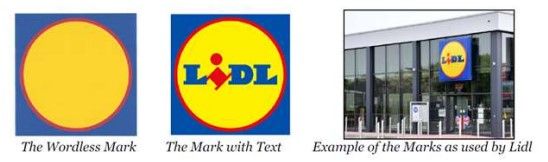

When bringing the claim, Lidl relied upon its trade mark rights concerning two versions of the Lidl logo: a logo with the word Lidl (the Mark with Text) and a logo without that word (the Wordless Mark).

Lidl's complaint concerned Tesco's use of the Sign below to promote its Clubcard scheme, which Tesco started using in September 2020.

In December 2020, Lidl issued proceedings against Tesco, alleging that Tesco was infringing its registered trademarks and copyright and was also guilty of passing off.

Lidl asserted that a significant number of customers would see Tesco's Sign and link it to Lidl's registered trademarks and believe that Tesco's prices were comparable to Lidl's prices or that they were price matched to Lidl's products.

Lidl argued that this would cause detriment to Lidl's brand (i.e. the dilution of Lidl's reputation as a low-cost discounter which offered better value for money) and would mean Tesco was taking unfair advantage of the reputation which resides in Lidl's trademarks.

In response, Tesco denied the allegations and issued a counterclaim for a declaration of invalidity and revocation of the Wordless Mark on the grounds of non-use and bad faith.

Tesco argued that the Wordless Mark had been registered as a defensive trademark and that Lidl had no intention of using it in trade but wished to secure a wider legal monopoly of trademark protection.

Tesco argued that this bad faith application was strengthened by Lidl's strategy of "evergreening," i.e. applying to re-register the wordless mark in a manner that bypassed obligations to prove the commercial use of the trademarks after five years of registration.

The Decision

The judgment passed down by High Court Judge Joanna Smith was a lengthy one (102 pages) and is somewhat reflective of the magnitude of the case and the prominence of the parties involved.

We have summarised some of the key findings below.

Trademark Infringement

The Court held that Tesco's Sign infringed Lidl's trademark rights by taking unfair advantage of Lidl's reputation for value and was detrimental to the distinctive character of the Lidl logo.

The Judge was not convinced that Tesco had deliberately intended to ride on Lidl's "coat tails".

However, the Court held that Tesco's Sign caused a "subtle but insidious" transfer of Lidl's image to Tesco and increased the appeal of Tesco's prices.

This led to a finding that Tesco had taken an unfair advantage of the reputation Lidl's trademarks have "for low price (discounted) value".

Copyright Infringement

The Judge found that copyright subsisted in Lidl's marks

because the incorporation of the yellow circle, blue square and the

Lidl text were an artistic work.

By incorporating the yellow circle within a blue square, the Judge

believed that Tesco's Sign consisted of a substantial part of

Lidl's Mark with Text.

Emphasis was placed upon the lack of evidence from Tesco's external branding agency, which appeared to have played an important role in developing Tesco's Sign.

Emphasis was also placed on the fact that Tesco seemed to change its story during the proceedings, starting with no explanation but ending up arguing that their Sign was an independent creation.

The Judge concluded that Tesco's "story", as

presented at trial, was "full of holes".

The Court went on to hold that Lidl's Mark with Text was copied

by Tesco's external brand agency "as part of their

exploratory work commissioned by Tesco and thereafter adopted by

Tesco".

Accordingly, Tesco had infringed the copyright in Lidl's Mark with Text.

Passing Off

Lidl's claim for passing off succeeded on the basis that they were able to demonstrate goodwill in their Mark with Text and Wordless Mark and persuade the Judge that a substantial number of consumers were led to believe that Tesco's prices represented the same value as Lidl's prices which led to Lidl suffering damage.

Tesco's Counterclaim

The Court held that the Wordless Mark had been validly used, even though it always appeared with the text 'Lidl', and therefore it could not be revoked for non-use.

Despite this, the Court held that at the time of filing its first trademark application in 1995, Lidl had no intention of using the Wordless Mark and had therefore acted in bad faith at the time.

The mark was registered purely as a "weapon" to secure a wider legal monopoly than that to which Lidl was entitled.

Comment

The Court's decision that Tesco had infringed on Lidl's registered trademarks has come as a surprise for many.

However, the reputation of Lidl's trademarks, the fact that

both parties operate in the same field, and the plethora of

evidence presented by Lidl could not be ignored.

With regard to bad faith applications, this decision serves as a

clear warning that an applicant's intention at the time of

filing remains key and filing in bad faith cannot be remedied by

later use of the mark.

This decision may make it very challenging for owners of

trademarks filed several years ago (where those involved may have

since left the business) to defend such allegations of bad

faith.

This decision also raises the point that reputational claims are

not just reserved for luxury brands.

Lidl's reputation of affordability is exactly what Tesco was held to be taking advantage of.

With the cost of living crisis, the majority of supermarkets are

shifting their focus to value for money, which may result in

similar types of reputational claims in the future.

It appears that the decision would mark the end of Tesco's

Clubcard promotion in its current form; however, Tesco has already

declared it will seek leave to appeal the decision, so this may not

be the end of the story.

To view original article, please click here.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.