- within Compliance topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Inhouse Counsel

- with readers working within the Healthcare industries

The early months of the new Unified Patent Court (the UPC) have passed with relatively little by way of problems and complaints. The general view is that the decisions have been clear, logical, prompt and accurate – you cannot ask much more of a court, let alone a brand new one.

However, it was inevitable that wrinkles might start to appear on the otherwise smooth face of the new court, and the case of Edwards Lifesciences Corporation v Meril Italy srl has certainly caused a few eyebrows to be raised. In this final update of 2023, we explore the details of this case, its progress before the UPC and the wider implications.

Summary of the case

- Under the rules of the UPC, if a patent infringement action has been commenced in a local division, a claim for revocation of the patent(s) in suit by one of the parties involved in the infringement case must be brought by way of counterclaim in the same case.

- In this case a wholly owned subsidiary of one of the defendants to an infringement claim (proceeding in the Munich Local Division) brought a separate revocation claim in the Paris Central Division. The infringement and revocation claims were in respect of the same patent.

- The patent owner applied to the Paris Central Division to have the claim struck out as it involved the 'same parties' as the Munich case.

- The judge-rapporteur considered arguments based on a literal interpretation, competition law, the provisions of the Recast Brussels Regulation, the straw company theory and the fair administration of justice. He concluded that the wholly-owned subsidiary was not a 'same party' and allowed the Paris case to proceed.

- He declined to award security for costs on the basis that the subsidiary, although small and without substantial funds, was part of a larger group, so there was no significant risk of not meeting any costs award.

Background

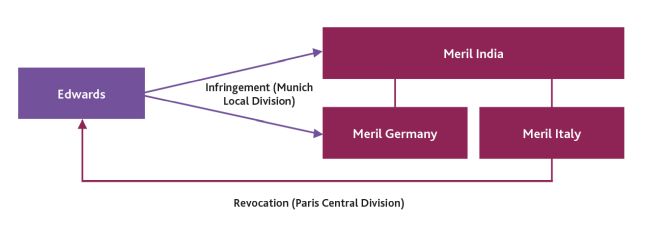

On 1 June 2023, Edwards Lifesciences Corporation (Edwards) commenced an action alleging infringement of its patent EP 3646825 against Meril Life Sciences Pvt. Ltd. (Meril India) and its subsidiary Meril GmbH (Meril Germany) in the Munich Local Division of the UPC.

On 4 August 2023, Meril Italy srl, (Meril Italy) a wholly-owned subsidiary of Meril India, commenced a revocation action in relation to patent EP 3646825 in the Paris Central Division.

The actions are illustrated below:

Edwards made an application for a preliminary objection in the Paris case, seeking a range of orders. Most importantly, it questioned the competence of the Paris Central Division seat, as an infringement action between the same parties on the same patent was already pending before the Munich Local Division.

Indeed, the UPC Agreement establishes (Art. 33(4)) the principle that revocation actions must be brought before the Central Division. However, it also provides that, if an action for infringement between the same parties and relating to the same patent has already been brought before a local/regional division, this revocation action may only be brought before the local/regional division hearing the infringement. This makes some sense, as on the face of it, it prevents duplication of the same issues being heard in multiple venues.

The judge-rapporteur, Mr. Paolo Catallozzi, a well-regarded Italian judge with a considerable amount of IP and competition law experience and a member of the European Patent Office's (EPO's) Enlarged Board of Appeal panel, considered the issue.

What are the 'same parties'?

The key to Meril's case was that Meril Italy is a totally separate legal entity, having separate headquarters from Meril India, and could not be said to be one of the 'same parties' in the Munich infringement action.

Edwards alleged that Meril Italy and Meril India are effectively the same party and their actions constitute an abuse of the Unified Patent Court framework, aiming to interfere with the infringement proceedings already pending before the Munich Local Division and to block the progress of those proceedings.

In the 13 November 2023 Order, the judge-rapporteur responded to all of the arguments raised by the parties.

Literal interpretation of the UPC Agreement

First, the judge-rapporteur considered whether the UPC Agreement provides a definition of the expression 'the same parties'. He noted that, while the UPC Agreement does not offer a simple definition of the term "party", it follows from Art. 46 (dedicated to legal capacity) and Art. 47(6) (entitled "Parties") of the UPC Agreement that it can be assumed that "a party is any legal or natural person or any body and the related assessment has to be carried out in accordance with its national law".

On that basis, since the revocation action was brought by the Italian subsidiary of the Meril group, he turned to Italian law, and concluded that the analysis leaned in favour of finding that Meril India and Meril Italy were not the same parties.

Moreover, the judge-rapporteur noted that the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU) has previously ruled that the concept of an undertaking "must be understood as designating an economic unit even if in law that economic unit consists of several persons, natural or legal" (C-97/08 - Akzo Nobel and Others v Commission). However, this argument also failed to convince as he noted that this definition only applies in the context of competition law.

The judge-rapporteur ultimately concluded that a literal interpretation of Art. 33(4) of the UPC Agreement results in the conclusion that Meril Italy and Meril India are different parties.

Brussels I Regulation Recast

Next, in response to Edwards' argument that the expression 'same parties' must be interpreted in accordance with the Brussels I Regulation Recast, the judge-rapporteur looked at the CJEU case law regarding the interpretation of Article 29(1) (Article 21 in the former version of the Regulation).

Art. 29(1) provides that "without prejudice to Article 31(2), where proceedings involving the same cause of action and between the same parties are brought in the courts of different Member States, any court other than the court first seised shall of its own motion stay its proceedings until such time as the jurisdiction of the court first seised is established."

After dismissing the interpretation set out in CJEU case C-351/96 – Drouot assurances v Consolidated metallurgical industries and others – (because it addressed a different legal issue), the judge-rapporteur held that the relevant provision of the Brussels I Regulation Recast is there to avoid duplicated litigation in multiple jurisdictions. He considered that there was no jurisdiction issue in the present case, the situation of parallel proceedings before the UPC being regulated by Art. 33 of the UPC Agreement.

Moreover, he held that the general principle governing the allocation of proceedings before the UPC is that revocation actions must be brought before the Central Division, while the rule that allocates revocation actions to the local/regional division where an infringement action is pending constitutes a narrow exception.

Therefore, the 13 November 2023 Order concludes that the above mentioned provision of the Brussels I Regulation Recast shall not govern Edwards' claim.

The conclusion adopted here by the judge-rapporteur deserves special attention. The reason why he considered that the interpretation of the terms "the same parties" given by the CJEU in the Drouot case is not relevant before the UPC is based on the view that Art. 29 of the Brussels I Regulation Recast is there to avoid duplicated litigation in multiple jurisdictions. However, Art. 33(4) of the UPC Agreement does not aim at dealing with that situation.

Ultimately the judge-rapporteur's conclusion may be controversial because:

- if counterclaims for revocation of a patent are brought before a local/regional division hearing the infringement action, and it decides not to refer the case to the Central Division (which it could decide under Art. 33(3)); and

- if the Central Division considers it has jurisdiction to rule on a revocation action brought against this same patent after the introduction of the infringement action...

...then the local/regional division and the Central Division could both rule on the validity of this patent, with a risk of issuing conflicting decisions. Therefore, one might have thought that the definition of 'the same parties' provided by the CJEU on the ground of the Brussels I Regulation Recast is relevant to define the same term before the UPC. Especially since EU law is one of the sources of law on which the UPC must base its decisions and, within the UPC system, takes precedence over national law.

The 'straw company' theory

Edwards also argued that Meril Italy was no more than a straw company with no real assets and, as such, it could not constitute an independent legal entity – its actions should be attributed to the parent company. To support this, Edwards pointed out that all the officers of Meril Italy are employees of Meril India, that Meril Italy does not have a physical presence in Italy and that its Italian registered office was that of a firm of accountants in Milan.

First, the judge-rapporteur looked at the concept of a 'straw company', and provided a definition:

"the described scheme relates to a situation in which properties are fictitiously registered in name of a person or, in general, a contract is fictitiously concluded by a person with the agreement that the property will be acquired by a different person or that the legal effects of the contract will be produced with regard to that different person. The assessment that a company is acting as a straw company requires legal activity that appears as related to it and the agreement that the relative effects will be produced in respect of a different entity".

The judge-rapporteur held that there was no evidence of any such agreement in this case (noting that the evidential burden to prove as such would be difficult), despite the strong connection between the two companies.

Interestingly, the judge-rapporteur referred to the case law of the EPO – and more exactly to the decisions of the Enlarged Board of Appeal, 21 January 1999, G-3/97 and G-4/97 – to conclude that the definition of a "straw company" he provided is compliant with the case law of the EPO. This explicit reference to EPO case law is interesting in that it demonstrates a will to ensure concordance between the two systems. An approach purely based on EU law, into which the UPC is integrated (unlike the EPO1), could have led to the development of an autonomous definition of the concept of a 'straw company'.

Uniform administration of justice

As mentioned above, the problem was that if the Meril Italy revocation action in Paris was allowed to proceed, Meril India and Meril Germany could still counterclaim for invalidity in Munich, effectively giving Meril 'two shots' at the Edwards' patent, and with the risk of having two divisions of the UPC issuing differing judgments in relation to the same patent.

Edwards argued that the purpose of the UPC is to achieve uniform administration of justice and avoid irreconcilable decisions within its divisions. However, the judge-rapporteur considered that the UPC had been provided with a 'set of tools' to handle the feared situation of parallel proceedings, allowing the Munich Local Division to stay the infringement action, pending the resolution of the Paris revocation action, or to transfer the infringement claims to the Paris Central Division to be joined with the action there. In other words, the tools available were to delay or prevent the Munich Local Division from hearing the action.

He also pointed to Rule 295 in the Rules of Procedure, which gives a general discretion to any UPC judge to stay proceedings if the proper administration of justice so requires.

The judge-rapporteur concluded that there was no risk of duplicated litigation in separate divisions of the UPC, and so dismissed Edwards' arguments.

Here again, the solution adopted by the judge-rapporteur deserves special attention. There is no doubt that this position is consistent with that expressed by the judge-rapporteur on Art. 29 of the Brussels I Regulation Recast – that the general principle governing the allocation of proceedings inside the UPC is that revocation actions must be brought before the Central Division, while the rule that allocates revocation actions to the local/regional division before which an infringement action is pending constitutes an exception.

Conclusion on the 'same parties' issue

Ultimately, the judge concluded that the revocation action in Paris did not "have a blocking effect" since that would depend entirely on the discretionary rights of the Munich judge as to whether to exercise his right to grant a stay. The same, he concluded, applied to the issue of "bifurcation by default".

Effectively, this decision grants the Paris Central Division a right of priority to rule on the validity of the patent, and it has some interesting consequences:

- It places responsibility for conflicting decisions solely with the Munich Local Division, even though this division was the first to receive the case, which may seem counter-intuitive.

- It generalises the bifurcation system, making the expected deadline of one year for a decision to be issued potentially untenable.

- It offers respondents in infringement actions an almost systematic alternative (the only condition being that they must have a subsidiary able to act before the Central Division) as to the place where the validity of the patent is assessed, which in practice may make the access to the UPC more complex and expensive.

Security for costs

Bearing in mind the lack of assets in Meril Italy, Edwards sought security for its costs under Rule 158 of the Rules of Procedure.

However, the judge-rapporteur considered that:

- The fact that Meril Italy does not run any business at present could be explained by its very recent establishment and the need to carry out preparatory activity.

- The low amount of share capital (EUR10,000) is not necessarily a sign of a lack of financial availability, taking also into account that the company is included in a corporate group and that there is no allegation that the group is in financial difficulties.

Therefore, the Order concludes that the fact that Meril Italy is not active in the market and has only limited share capital does not mean that it will not be able to meet any award for reimbursement of costs.

Thus, the judge-rapporteur considered that, if Meril Italy had to bear the financial consequences of a decision of the Central Division ruling in favour of Edwards, it could rely on its parent company, Meril India, whose finances would enable it to meet the cost.

What are the wider implications of this case?

When assessing whether Meril Italy can be considered as a party, the judge-rapporteur relied on Italian law which provides that the capacity to be a party requires the general aptitude to be recipient of the legal effects of the judicial proceeding. However, if Meril Italy is not able to bear the financial consequences of a decision of the Central Division ruling in favour of Edwards, can it really be considered as having the aptitude to be recipient of the legal effects of this judicial proceeding?

It might be unwise to draw too many conclusions from this, and it seems likely that the ruling will be subject to an appeal, but there does appear to be a material inconsistency here.

Perhaps the bigger issue with this judgment is that it effectively opens the door to widespread bifurcation "through the back door", while those who created the UPC system did not appear to intend that it would feature bifurcation as a regular event. What is to stop any respondent in an infringement action creating a nominal subsidiary in any UPC country then relying on this ruling to justify bringing a separate revocation action in the Central Division through the new entity? Further, there seems to be no protection for the patent owner in relation to security for costs in the event that the revocation action fails.

The 13 November 2023 Order is certainly as surprising as it is interesting, and while its outcome may seem controversial, in hindsight it confirms that the texts in force still leave plenty of room for interpretation and that it would be wise - pending harmonisation by the Court of Appeal - not to presuppose the meaning given by certain provisions.

Footnote

1. The European Patent Convention being a multilateral treaty distinct from EU law.

Read the original article on GowlingWLG.com

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.