- within Finance and Banking topic(s)

- in United Kingdom

- with readers working within the Retail & Leisure industries

- within Antitrust/Competition Law, Intellectual Property and Real Estate and Construction topic(s)

On Friday 1 August, the Supreme Court allowed the appeal of lenders, finding that (i) credit brokers do not owe a fiduciary duty when they recommend finance to car buyers; and (ii) given the absence of fiduciary duty, commissions paid cannot be likened to a bribe.

Had the Supreme Court found differently on these points, the implications for financial services in widening the net for redress would have been massive.

Markets in the shares of exposed lenders have responded well and executives at those firms may still be able to enjoy some of time off in August. However, there remain important issues at stake, and lenders and brokers will need to think carefully about how best to engage with the FCA as it consults on the redress scheme that it will seek to launch.

What about Johnson?

One of the three cases heard concerned Mr. Johnson and First Rand. Unlike the other two cases in front of the Court, Mr. Johnson had claimed that the relationship between him and the lender had been unfair under the Consumer Credit Act. In rejecting the arguments of the lender, the Supreme Court agreed with Mr, Johnson that the relationship was unfair, establishing a basis for a different type of claim (CCA Unfair Commission). In forming this view, five points were explicitly called out in Lord Reed's summary of the judgment:

- The level of commission: the lender had paid the broker a commission of £1,650.95, which was 55% of the £3,023.20 finance costs of the car (interest and fees) and 26% of the advance of credit (£6,399);

- The nature of the commission: a discretionary commission may, for example, create incentives to charge a higher interest rate;

- The characteristics of the consumer: Mr. Johnson had failed to read the documents and was described by Lord Reed as commercially unsophisticated;

- The extent and manner of disclosure that was made: the documents had disclosed that a commission may be paid and although Mr. Johnson had signed those documents, he denied having any understanding. There was also no disclosure of the commercial tie between the lender and the broker that might have alerted Mr. Johnson to the incentives of the broker;

- Compliance with regulation.

In reading the summary, Lord Reed was careful to make clear that this was not an exhaustive list. Although there is no explicit priority given to these considerations in the judgment, it is clear that the size of the commission relative to the cost of finance was held to be a 'powerful indication' of the unfairness of the relationship.

What does Johnson mean for Discretionary Commission Arrangements (DCAs)?

The FCA's work on DCAs and, in particular, the design of a redress scheme had been stayed pending the Supreme Court ruling.

The Johnson case provides legal clarity on the issues that a court might want to consider in determining fairness under the Consumer Credit Act. By incorporating the nature of commission and whether or not adequate disclosure had been made in the list of considerations, the FCA will consider that their initial plans to develop a scheme covering non-disclosed DCAs is appropriate.

Whether or not every undisclosed DCA arrangement would be successful in the Courts is a different matter.

Would the Courts consider a relationship where a DCA resulted in commission of, say, £500 against finance costs of £5,000 (10%) as being unfair – even if there had been no disclosure?

Would the Courts consider a DCA unfair if the car buyer was an accountant who might have been expected to read the documents in front of her and press on the commission point – even if it was not disclosed upfront?

A redress scheme could attempt to filter out those exceptions that would not have met the unfairness threshold. However, the FCA might prefer the clarity of saying that regulation was clear and lenders should have disclosed these arrangements. A catch-all scheme.

What about CCA Unfair Commission Claims?

The Court was clear that the specifics of each case matter in assessing whether an arrangement might be fair. For example, the Court stated that an absence of disclosure is not necessarily evidence that a relationship is unfair. It was also accepted that there is an obvious asymmetry between a broker and a customer, but that did not mean that every car buyer should be considered commercially unsophisticated.

Will these claims be brought within a scheme?

Given the guidance of the Court to consider these CCA Unfair Commission claims by reference to the specifics of the situation, the FCA will want to carefully consider whether inclusion within an industry wide redress scheme is appropriate.

The FCA certainly seems minded to bring them within the Scheme. The regulator wants to bring clarity and ensure that those who are due compensation are paid as quickly as possible. It also may make sense for firms, in that they could establish rules-based processes that ensure consistency in the way in which complaints are handled.

If the FCA were to require firms to bucket CCA Unfair Commission cases by reference to: level of commission; characteristics of buyer; and adequacy of disclosure, then you could imagine that some broad rules might be drawn about whether a fairness or unfairness threshold had been breached.

What will the FCA need to consider in developing the Scheme?

In its market briefing, the FCA gave market guidance that it believed the industry cost of the redress scheme (including administrative costs) would be between £9 billion and £18 billion. This is obviously a very broad range and reflects three key elements: scheme coverage, calculation of damages, and take-up.

Scheme coverage

The first aspect will be timescale. Although there have been some questions about whether it is appropriate to go back until 2007, this appears to be the period that the FCA have considered in their scenarios. Although DCAs were banned from January 2021, it would be quite possible to include CCA Unfair Commission claims beyond that period.

Filtering out fair DCAs

As discussed, it would be possible to exclude undisclosed DCAs if they failed to meet the unfairness threshold.

Calibration of unfairness parameters:

If a commission at 55% of the finance costs represents a powerful indication that the relationship is unfair, what level might be considered a mild indication or suggest fairness? The FCA has provided some statistics on the volume (500,000) of non DCAs that might meet two distinct thresholds (40% of finance costs and 20% of the loan advance). Although it has not said that these are the thresholds it was looking to apply, it is interesting that the CEO of the FCA was able to quote these statistics (albeit for the period before 2021).

Mr. Johnson was described as commercially unsophisticated by the Supreme Court. Reading a summary of his evidence suggests that he was presented with many documents to review and sign which he says he did without reading or understanding them. A visit to a dealership on the Saturday following the judgment suggests that "readers", as the broker called them when discussing financing arrangements, were unusual. This feels like a low bar, but if the parameters for judging borrower characteristics were more specific, then it could raise a question of how the data to support these characteristics might be gathered.

The adequacy of disclosure. Although the documentation might present a relatively clear view of the disclosure, there will be little evidence other than the recollections of the customer and (at a push) the broker of what was said and when.

In view of the difficulties of gathering evidence on the characteristics of the customer and the level of disclosure that was provided, it seems likely that a lot of dependence would need to be taken on the commission levels paid if CCA Unfair Commission cases were included in the Scheme.

Calculation of damages – a question of harm

The Supreme Court acknowledged that the CCA confers very wide powers in establishing remedies. In Mr. Johnson's case, the Court determined that he should be awarded the commission paid, plus a commercial rate of interest. If a commercial rate of interest was interpreted as being 3%, then the damages payment made might be around £2,150. This level of redress might have encouraged the claim management companies (CMCs) who have said that individuals will be able to claim thousands of pounds.

Drawing up estimates on this basis does not appear in line with FCA guidance, however:

- The FCA has previously warned CMCs to review their promotional materials to avoid potential breaches of conduct regulation;

- Following the Supreme Court's judgment it has said that it regards some of the loss estimates that CMCs have been advertising as being "highly speculative";

- It has confirmed that it expects compensation to be lower than £950 per agreement, and has said that it does not consider that the approach taken by the FOS in previous decisions is necessarily the one it would adopt for a Scheme.

What should the FCA be considering?

Ordinarily, the Courts might expect to seek to contrast the factual scenario that a claimant finds itself in with a counterfactual – the "But For?". When the FOS has considered the But For in non-disclosed DCA cases, it has concluded that – in the absence of a DCA – the broker would have offered the car buyer the best possible rate of interest that they would have been eligible for. The calculation then requires contrasting two sets of interest cash flows to determine the impact on the car buyer. Compensation was awarded for this differential, together with an allowance for the time value of money.

The FCA clearly has concerns about this approach and might be encouraged to conclude that the FOS approach is overly simplistic. Although it is quite clear that discretionary commission arrangements might create a conflict of interest, is it reasonable to conclude that, in the absence of these arrangements, car buyers would have got the best rate that had been available at the time? The best rate available would not, in our view, have been the lowest available factual rate (quite probably, a rate at which the broker would have received modest or no commission). The correct rate for comparison is the best rate available in that counterfactual world. This counterfactual rate would, in our view, have to include some increment to allow for the payment of a reasonable level of dealer commission.

Is the application of the counterfactual interest rate a complete analysis?

This analysis of the counterfactual interest rate ignores the reality of how people buy cars. For there to have been true harm to car buyers on an industrial basis, one or both of the other parties (dealers and lenders) must have made extortionate profits. We have seen no evidence that this is the case: car dealerships operate in an extremely competitive environment, an environment where flexibility in the way in which the package of car and financing arrangements allow them to shape a deal to secure a buyer. Similarly, lenders compete to be a partner of the dealer that might be considered by their customer for finance. In a competitive market, we would expect any excess profits to be competed away.

Box A considers the economics of car-buying and questions whether there can be any routine harm caused to a car buyer in such a competitive environment.

Take-up

The FCA has made no decision about whether the Scheme should operate on an "Opt-in" basis or an "Opt-out" basis. This question is fundamental to the level of take-up that we might expect to see. An Opt-out scheme would essentially require firms to identify any customer that might be captured by the parameters that the FCA calibrates. An Opt-out scheme clearly involves complexity in identification of individuals as well as tracking those individuals who may have changed address multiple times since their last contact with the dealership.

For the non-disclosed DCA, it should be relatively straightforward for firms to identify the time period during which a DCA existed with a specific dealership. Understanding whether adequate disclosure was made might be more difficult and the FCA might put the onus on the firm to demonstrate that appropriate disclosure was made. Few car buyers are likely to exclude themselves from compensation if they receive a letter saying that they could be due compensation from their dealer.

In relation to claims that might be considered under the broad CCA unfairness test, it seems to us that an Opt-out Scheme would have further complications given the specific nature of such claims. Unless the FCA creates a short cut that focuses on the level of commission paid, it seems to us it should be for the car-buyer to establish the grounds on which he or she considers they were treated unfairly.

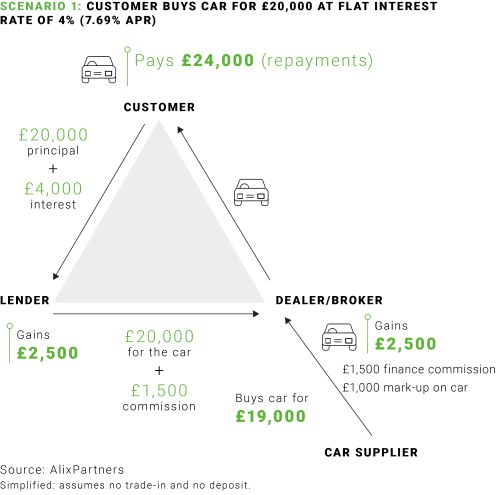

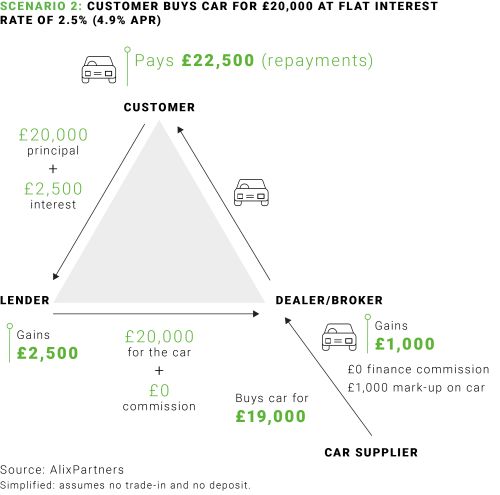

Box A. How the economics of a car purchase can vary

- Scenario 1 - discount on the car: Mrs A negotiates a discount on the new car of £1,500. She agrees to pay the £20,000 net amount through a finance agreement of £400 per month for five years. The finance cost, £4,000, equates to an annual percentage rate (APR) of 7.69% (4% flat). Of this £4,000, £1,500 pays the dealer commission.

- Scenario 2 - No commission on the finance: Mrs A pays £22,500 through 60 monthly repayments of £375 at a flat rate of 2.5% (APR of 4.9%). Lender Z generates the same revenue (£2,500). Dealer makes £1,000 through the mark-up on the car. The dealer makes no commission on the car finance.

- Mrs A chooses a car with a sticker price of £21,500, which the dealer purchased for £19,0001.

- The car dealer is also a credit broker and selects Lender Z from a panel of lenders.

- Lender Z operates a DCA with the broker. The DCA allows the dealer/broker to take any interest above minimum flat rate2 of 2.5% as commission.

However, scenario 2 is not realistic:

The economics of the deal rather than the shape of the deal matter in the real world. Often it is the monthly repayments that matter most to the consumer, not the overall cost of the car. The overall revenues that the dealer / credit broker is able to generate do matter to the profits of the broker. All else equal, the dealer / credit broker will only agree to the deal if there is enough margin available. In essence there is a waterbed effect: If the broker cannot make commissions on the finance, then the margin on the car will need to increase.

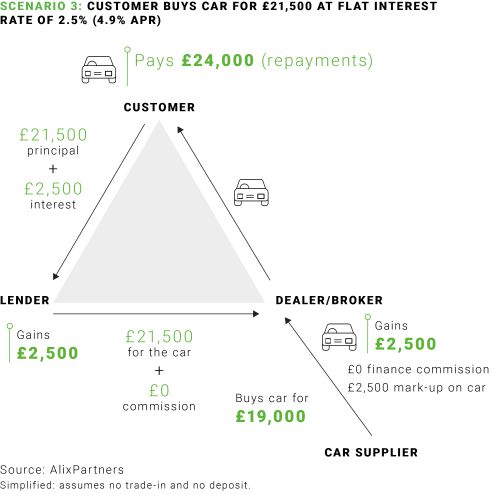

Scenario 3 demonstrates how the price of the car must change to keep the overall economics of the deal the same:

- Scenario 3 - No discount on the car: Mrs A pays £21,500 for the car and £2,500 in interest. The lender generates revenue of £2,500 on the finance and the dealer/broker brings their revenue back up to £2,500, replacing the lack of commission with a greater mark-up on the sale of the car.

Take-up

The FCA has made no decision about whether the Scheme should operate on an "Opt-in" basis or an "Opt-out" basis. This question is fundamental to the level of take-up that we might expect to see. An Opt-out scheme would essentially require firms to identify any customer that might be captured by the parameters that the FCA calibrates. An Opt-out scheme clearly involves complexity in identification of individuals as well as tracking those individuals who may have changed address multiple times since their last contact with the dealership.

For the non-disclosed DCA, it should be relatively straightforward for firms to identify the time period during which a DCA existed with a specific dealership. Understanding whether adequate disclosure was made might be more difficult and the FCA might put the onus on the firm to demonstrate that appropriate disclosure was made. Few car buyers are likely to exclude themselves from compensation if they receive a letter saying that they could be due compensation from their dealer.

In relation to claims that might be considered under the broad CCA unfairness test, it seems to us that an Opt-out Scheme would have further complications given the specific nature of such claims. Unless the FCA creates a short cut that focuses on the level of commission paid, it seems to us it should be for the car buyer to establish the grounds on which he or she considers they were treated unfairly.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.