On 6 September 2023, the Law Commission of England and Wales ("Law Commission") published a Final Report outlining its recommended reforms to the Arbitration Act 1996 (the "Act"), with an accompanying draft Bill. The Final Report recommends a "few major initiatives", including the introduction of a new statutory, default rule that the arbitration agreement will be governed by the law of the seat ("Default Rule"), unless the parties expressly agree otherwise.

There has been a longstanding debate in the English courts and arbitration community as to whether the law governing the arbitration agreement should, in the absence of an express choice, align with the general choice of law in the matrix contract or with the law of the seat; the English courts have come out on both sides of the fence. By adding the Default Rule into the Act, the Law Commission seeks to promote certainty and remove opportunities for satellite litigation on this complex issue.

If adopted, this Default Rule would replace1 the current position as decided by the Supreme Court in Enka2- a general rule that, in the absence of an express party choice, the law of the matrix contract governs the arbitration agreement (when such law was expressly chosen by the parties). The Law Commission's proposal therefore has significant ramifications for parties with arbitration agreements3 with an international dimension.

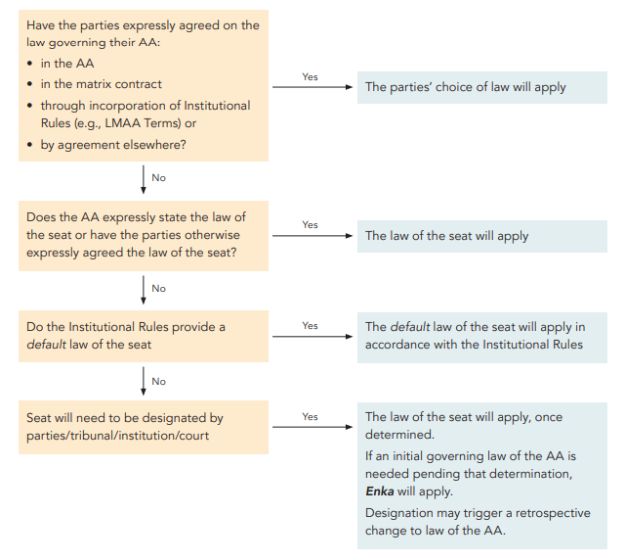

In this Legal Update, we summarise the current law and the practical significance of the law of the arbitration agreement, set out the Law Commission's proposed reforms, and provide some preliminary observations. We explain the implications for parties with arbitration agreements with a multi-jurisdictional dimension (i.e. where the law of the matrix contract is not the same as the law of the seat) if this proposal were to become law, and provide a practical flowchart for parties to ascertain the law governing their arbitration agreements. You can click on the links to those sections in this paragraph to navigate quickly between the sections.

Background to the Law Commission's Proposed Reform

The Law Commission is an independent statutory body that keeps the laws of England and Wales under review and recommends reform where it is needed. Pursuant to a request by the UK Government, the Law Commission reviewed the Act, which provides the framework for arbitration in England and Wales and Northern Ireland, and issued its Final Report proposing amendments designed to ensure that the Act (i) remains fit for purpose; and (ii) continues to promote England and Wales as a leading destination for commercial arbitrations.

The Significance of the Law of the Arbitration Agreement

The law governing the arbitration agreement applies to matters relating to the formation, existence, scope, validity, legality, interpretation, termination, effects, and enforceability of the arbitration agreement. The need to determine this law can arise at any stage of an arbitration. For example, it may be relevant if a party:

- contests that it is bound by an arbitration agreement;

- argues that its arbitration agreement is not valid;

- argues that the governing law of the arbitration agreement includes an implied term of confidentiality;

- argues that a claim or a subject matter is outside the scope of the arbitration agreement;

- has a dispute about the interpretation of the arbitration agreement; or

- disputes the tribunal's

In practice, though, courts often grapple with determining the law of the arbitration agreement at the enforcement or annulment stage and, due to differences in approach, courts around the world often take different views on the very same circumstances (see our Legal Update on the clash between the French andthe English courts over the law of the arbitration agreement).

The Current Law

The 2020 UK Supreme Court's decision in Enka4 represents the current law, which is complex, but can be distilled as follows:

- The law applicable to the arbitration agreement will be the law chosen by the parties to govern

- If there is no express party choice, as a general rule, the governing law of the matrix contract will apply (as an implied choice) to the arbitration agreement.

- However, that general rule may be displaced in some circumstances (for example, where the law of the seat itself provides that the arbitration agreement is governed by the law of the seat, or where there is a serious risk that the general rule might render the arbitration agreement invalid).

- If there is no choice of law anywhere, the arbitration agreement will be governed by the law with which it has the closest and most real connection. According to the majority of the judges deciding this case, this will be the law of the seat of the arbitration (although, again, that may be displaced if there is a serious risk that it might render the arbitration agreement invalid).

While the Enka decision is an orthodox application of conflict of laws rules found in the New York Convention, the Law Commission commented that it is "complex and unpredictable"5, and leaves significant room for argument on any given case. The upshot is that it is currently difficult for parties to have certainty as to how English courts (and tribunals) determine this law, as evidenced by the fact that in Enka "the Supreme Court itself was divided on both the law and how to apply the law to the facts"6.

The Law Commission's Proposal

The Law Commission has prepared a draft Arbitration Bill which proposes a new section 6A of the Act which, in part, says:

"The law applicable to an arbitration agreement is -

- the law that the parties expressly agree applies to the arbitration agreement, or

- where no such agreement is made, the law of the seat of the arbitration in question".

The proposed section also states that the fact that the parties have chosen a law to govern the matrix contract does not itself constitute an express choice of the law of the arbitration agreement. Importantly, the new Default Rule would apply:

- to arbitration agreements entered into on or after the date that the new section 1 comes into force;

- whatever the seat; and

- whether the seat was chosen by the parties or otherwise

The Default Rule can therefore only be displaced by express party agreement. Parties may be able to agree on the law of the arbitration agreement either in the arbitration agreement itself, elsewhere in the matrix contract or in some other manner (in writing or orally). However, should parties only turn their minds to the law of the matrix contract, that choice of law will no longer be helpful in ascertaining the law of the arbitration agreement as, unlike the current law, the proposed new law does not allow for an implied choice of governing law for the arbitration agreement.

Practical Flowchart for Parties

The Law Commission's proposal means that parties will need to answer the following questions to ascertain the proper law governing their arbitration agreements once the new law takes effect. Arbitration agreements are referred to as "AA" in the below flowchart.

What the Default Rule would Mean for Parties with Arbitration Agreements with a Multi-Jurisdictional Dimension

- Parties with pending or imminent arbitrations, or arbitration awards, which relate to arbitration agreements pre-dating the date of the new law, can continue to rely on Enka. Parties only need to concern themselves with the requirements of this new law if their arbitration agreement is entered into after the reform takes effect (likely to be 2024).

- The seatbecomes a critical component of an arbitration agreement: the flowchart proves how critical the choice of the seat will become to determine the law of the arbitration This is because it remains uncommon for arbitration agreements to expressly state the law governing the arbitration agreement. Unless and until this practice becomes mainstream, there will be a need to specify the seat in the arbitration agreement to avoid the uncertainties and costs of the parties, institution, tribunal, or court (as per the circumstances) determining the seat.

- Goodbye validation principle: the law of the seat would apply even if such law would render the arbitration agreement The Default Rule therefore removes the validation exception outlined in Enka, namely that the choice of law for the matrix contract might not also apply to the arbitration agreement if that choice of law would render the arbitration agreement invalid. This is a potential disadvantage of the new rule, as it means that parties need to think carefully about their choice of seat and ascertain any risks in terms of a particular choice causing validity issues for the arbitration agreement. If that law were to be unfavourable to arbitration, then another law should be chosen7.

- Very few institutional rules provide a default law of the arbitration agreement that, by virtue of their incorporation in the arbitration agreement, becomes the parties' 'choice'. Most rules, including the ICC Rules, are silent on this topic. One example, however, is the LMAA Terms 2002, 2006, 2012, 2017 and 2021 which set English law as the default applicable law (unless the parties agree otherwise).

- It is best to expressly state the law governing the arbitration agreement: for best protection and certainty, it has always been advisable that parties expressly specify the law governing the arbitration agreement in their arbitration clause, and while the Default Rule would remove a large degree

of uncertainty, that remains unchanged (i) in the interests of avoiding satellite disputes (see "Our Preliminary Observations" below); and (ii) in light of the emphasis placed on express party agreement in the proposed new law.

Our Preliminary Observations (if the Default Rule Becomes Law)

- A simpler solution overall: having a clear, easily navigable rule which applies at all times (enforcement of the agreement to enforcement of the award), and whatever the seat, will be simpler for parties and their counsel than having to navigate the Enka decision, with its many nuances, and hence helps "establish expectations"8 for arbitral users.

- Party autonomy fully respected: it might be considered the right choice that the new provision starts with an expectation of express party agreement and that such agreement always trumps the Default Rule, as this means that party autonomy remains paramount.

- Applying the Default Rule to an arbitration with any seat offers clarity and should mitigate the scope for arguments about the law of the arbitration agreement in enforcement It should help avoid contradictory outcomes, like those regarding the validity of the award in Kabab-Ji.

- Fewer disputes about the law of the arbitration agreement but disputes will remain: with the Default Rule, there should be no more disputes about implied choices or those relating to the appli- cation of the validation principle and less scope for satellite arguments on the position under foreign law relating to arbitrability, scope and separability. The Default Rule should provide an easily referable and certain rule in the vast majority of cases (meaning fewer disputes) but for the remaining small minority, where the seat is unspecified, uncertainty remains, and disputes are still There could also be disputes over what amounts to express party agreement (for the purposes of the law of the arbitration agreement itself or the seat) and it will be interesting to see if English courts follow the recent Singapore Court of Appeal decision which held that "an express choice of law for an arbitration agreement would only be found where there is explicit language stating so in no uncertain terms."9

- Jurisdictional divergence remains: the Default Rule would make English arbitration law consistent with the LCIA Rules 2014 and 2020 as well as other legislation such as Sweden's Arbitration Act and the position adopted in jurisdictions like the It also brings English law closer to Scottish law, which also provides a default rule in favour of the law of the seat, but which is worded differently - the default rule applies "unless the parties otherwise agree" (and hence risks being trumped by an implicit choice of law to govern the arbitration agreement). However, the Default Rule would create a divergence of approach vis-à-vis other jurisdictions, such as Hong Kong and Singapore, whose jurisprudence has arisen out of and developed based on the English common law10, countries like Switzerland that adopt a validation approach, and others that adopt an approach not aligned with a national law (like France). If the Default Rule is adopted, it will be interesting to see if any other jurisdictions follow suit.

Next Steps in relation to the Bill

It will be down to the UK government to decide whether to introduce the Bill into Parliament. While the future of the Bill remains to be seen, in the arbitration community the strong sentiment appears to be that the UK Parliament will likely adopt this Bill and, if it does, it will likely become law in early 2024.

Further Legal Updates

We will provide further Legal Updates on the development of this Bill in addition to the Law Commission's other proposed legislative changes to the Act.

Footnotes

1. In all circumstances, save for when there is no seat of arbitration designated as the Law Commission's Final Report confirms that the English common law principles will apply, pending such determination.

2. See https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uksc-2020-0091-pdf.

3. An arbitration agreement is the same as an arbitration The terms are used interchangeably.

4. See https://www.supremecourt.uk/cases/docs/uksc-2020-0091-judgment.pdf. The Supreme Court endorsed Enka in Kabab-Ji SAL v Kout Food Group [2021] UKSC 48, discussed further in our prior Legal Update.

5. Law Commission's Final Report, paragraph 138.

6. Ibid.

7. The Law Commission's view is that given the pro-arbitration stance taken by the law of England and Wales, it would be "rare" for an arbitration agreement to be invalid under the law of England and Wales.

8. Paragraph 12.44 of the Law Commission's Final Report.

9. See Anupam Mittal v Westbridge Ventures II Investment Holdings [2023] SGCA 1, para

10. The Supreme Court decision in Enka and prior Court of Appeal decision in Sulamérica, respectively.

Originally published 11 September 2023

Visit us at mayerbrown.com

Mayer Brown is a global services provider comprising associated legal practices that are separate entities, including Mayer Brown LLP (Illinois, USA), Mayer Brown International LLP (England & Wales), Mayer Brown (a Hong Kong partnership) and Tauil & Chequer Advogados (a Brazilian law partnership) and non-legal service providers, which provide consultancy services (collectively, the "Mayer Brown Practices"). The Mayer Brown Practices are established in various jurisdictions and may be a legal person or a partnership. PK Wong & Nair LLC ("PKWN") is the constituent Singapore law practice of our licensed joint law venture in Singapore, Mayer Brown PK Wong & Nair Pte. Ltd. Details of the individual Mayer Brown Practices and PKWN can be found in the Legal Notices section of our website. "Mayer Brown" and the Mayer Brown logo are the trademarks of Mayer Brown.

© Copyright 2023. The Mayer Brown Practices. All rights reserved.

This Mayer Brown article provides information and comments on legal issues and developments of interest. The foregoing is not a comprehensive treatment of the subject matter covered and is not intended to provide legal advice. Readers should seek specific legal advice before taking any action with respect to the matters discussed herein.