- within Intellectual Property topic(s)

- in North America

- within Transport, Food, Drugs, Healthcare, Life Sciences, Government and Public Sector topic(s)

In addition to concerns about data protection and confidentiality, the fear of copyright infringement is the second major obstacle for many when using artificial intelligence. In practice, however, the risk is not very high, at least for those who use prefabricated AI models – if a few rules are observed. We look at this in part 14 of our AI blog series.

First of all, a brief overview of where the problem of third-party rights to content may arise, especially when using generative artificial intelligence. This is not only copyright law, but also unfair competition law and possibly special legal provisions. For example, depending on the legal system, it may be prohibited to copy and use the commercial results of the work of others without a reasonable effort on your part (Art. 5 of the Swiss Unfair Competition Act), or to copy entire or large parts of third-party databases, even if they are not protected by copyright (EU Directive on the Legal Protection of Databases). In part 10 of our AI blog series, we discussed in detail the responsibilities of AI providers and users when it comes to third-party rights.

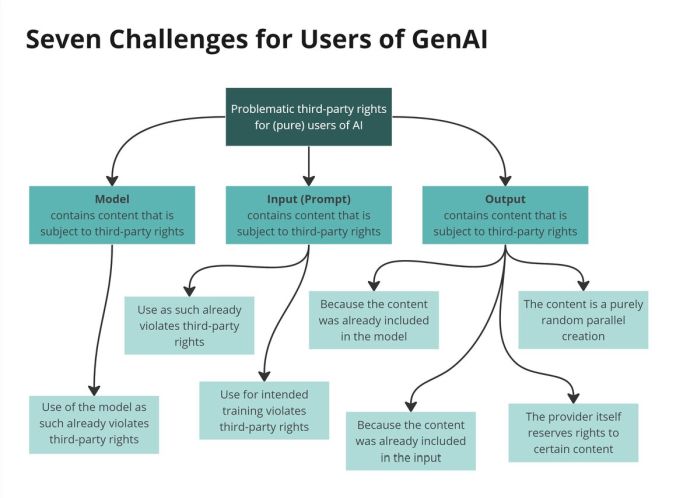

Seven challenges

When copyright and similar topics are at issue, users of AI systems that rely on prefabricated AI models will face challenges in three areas:

- Model: The AI model used "contains" copyrighted third-party content because it has been trained with such content without a sufficient legal basis. Several court cases are currently underway to clarify this issue. The user will generally not know, or not know exactly, how the AI model he is using has been trained, i.e. there is little he can do about it, and he will receive little information that could help him choose a model.

- Input: The input that feeds an AI system contains copyrighted third-party content for which there is no adequate legal basis for its intended use. This use can consist of either the generation of outputs (the input is then also the "prompt") or the training or fine-tuning of the AI model (the input is used to adjust the parameters of the AI model so that outputs generated with it later become "better").

- Output: The output generated by the AI system contains copyrighted third-party content. This can happen for four main reasons: First, the AI system may generate such content because its model recognises it as a result of its training, even if the user does not want it to. Depending on the AI technique, this will only happen in practice if the content in question has been presented to the model often during training, and there is therefore a high probability that the model will consider this content to be the correct response to the corresponding prompt (more on this below). Second, such an output can be generated based on the user's input, either because the AI system was given the content in question with the prompt, or because the prompt contains an instruction to "recreate" the third-party work. Third, an AI system may in fact generate content that corresponds in relevant parts to an existing work, but this is nevertheless a random result (more on this below). Fourth, the provider of an AI system (or the service provider offering it as a service) may claim the output as its own work; although it will not normally be able to rely on copyright law to do so if the work is entirely machine-generated, it may be able to secure rights in the work vis-à-vis the user by contract and, if necessary, by other laws such as unfair competition law.

Here is a graphic overview of the seven challenges:

This description of the challenges does not take into account the fact that even where the rights holder has not given permission to use content, such use may be permitted by law (e.g. citation right, personal use, use for science and research). Whether such a "fair use" provision applies must be considered on a case-by-case basis. These cases are not discussed in detail in this article. We will also not discuss the training or development of AI models here. We will address some of these issues in a separate article. We also do not address patent and trademark rights, which may also be infringed.

Copyright is not unlimited

A user must address all seven of these challenges in order to use generative AI without worrying about the copyrights and other IP rights of third parties. Before we look at the practical steps that can be taken to achieve this, we would like to make a few preliminary remarks that we believe are important for the legal understanding of our recommendations. However, they reflect the personal view of the author, are not undisputed, may vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction, and are primarily aimed at those readers who are interested in the topic of copyright protection in the use of generative AI in particular (those who are not can skip directly to the "Recommendations for practice" section):

- First, it must be remembered that copyright, at least in our legal system, is only granted for human creations or expressions of mind, i.e. the work must have been conceived by a person. With certain exceptions, such as photographs (see third point below), the work must also have an individual character, also referred to as originality (see below). A work created solely by a machine acting autonomously in this respect is not protected by copyright. This does not mean, however, that the output of generative AI is not protected by copyright per se. To the extent that the output of such an AI reproduces elements which are an intellectual creation and which otherwise meet the requirements for copyright protection, it will be entitled to protection. For example: A user comes up with an unusual, creative image composition, writes a corresponding prompt and the computer generates an image from it. To the extent that it reproduces the original and unique composition, the AI output is protected in relation to that composition. Here, generative AI is merely the tool for rendering an existing work (in the form of the prompt). If, on the other hand, the prompt is too "normal" or does not specify the individual elements of the output, the image based on it is not protected by copyright, because it is not the expression of a human mind, but of a machine acting autonomously in this respect.

- Second, a copyright holder's rights are generally only

infringed if a second work still contains characteristic elements

of the (specific) work of the initial copyright holder. There is no

infringement if a copyrighted work has been used only as an

inspiration or idea, but the work's individual character is no

longer recognisable in the second work or has faded in comparison

to the originality of the AI's output, whereby circumstances

such as the creative scope and the "internal distance"

between the first and second work must also be taken into account.

In practice, it depends on the overall impression of the person who

knows the first work: the originality of the first work must be

compared with the originality of the second work and assessed as to

how closely they match. Conceptually, however, the first work will

usually be considered as having been "used" in the

creation of the second work (even if no copy of the work has been

made), since copyright generally only protects a rights holder

against his own work being used without authorisation (Switzerland:

Art. 10 Copyright Act). As a consequence, a second work

created independently should not be considered as

infringing the first work even if it looks the same. While this is

recognised in some legal systems, the issue is controversial and

unresolved in Switzerland, probably also because it has so far been

regarded as a more or less theoretical construct, as no one could

imagine how such a situation could arise. It has been argued that

even if there was no conscious adoption of the first work, the

creator of the second work was probably nevertheless subconsciously

aware of it and it therefore influenced the creation of the second

work. In view of the possibilities of generative AI and how it

creates content, the case of an independent parallel creation will

have to be discussed anew – because of the way certain models

work, independent parallel creation is no longer only a theoretical

case. While the previous doctrine and case law on this topic was

developed only for secondary creations by humans, there is nothing

to prevent it from being applied to the output of generative AI. To

begin with, this means that an AI user is legally responsible for

what he does with the output generated by the AI tool he may use,

as if he had written or otherwise created it himself (for purposes

of criminal or civil liability further aspects such as his

knowledge and diligence will be relevant, too). Accordingly, if the

work created by an AI infringes someone else's copyright

because it has the individual characteristics of a pre-existing,

protected work and the AI's user has neither the rights

holder's consent nor a fair use exception to rely on, he may be

prohibited from using such secondary work. If, however, it can be

shown that the AI actually did not rely on the specific original

work at issue to create the secondary work, then the situation must

be different. Let's leave the burden of proof question open at

this point, and focus on how AI models work, at least those that

are based on the "transformer" technology, such as GPT or

Dall-E. They normally do not use the individual texts and

images that they have been trained with as a kind of template to

create the output that their users ask them to create with their

prompts. Whereas the use of such works for training an AI model may

constitute a copyright infringement, these works are usually no

longer found within the AI model once it has been trained. A copy

of the work can only be reconstructed in exceptional cases, and

even then only with the correct prompt. The fact that the trainer

may have infringed the rights of these works can therefore not be

held against the user of the model, at least as long as these two

conditions are not met. For example, a language model does not

contain a copy of the documents used in the training, but –

to put it simply – only numbers (so-called weights) that

reflect the meaning of the words in relation to various aspects.

These weights are derived from the words in the documents used for

training. The better the AI model can determine the meaning of the

words in the input (i.e. the prompt) using these weights, the

better the model will be able to predict the word that is –

in view of the training materials – most likely to follow the

previous text. This is the sole function of a language model. To a

large extent, the meaning of words is not referred to in absolute

terms, but in relation to each other ("uncle" relates to

"aunt" as "man" relates to "woman").

Each individual piece of text viewed during training influences the

relationships and other meanings of the words stored in the model

as numerical values. It would therefore be useless to store the

work as such in the model, because it cannot be used as a basis for

calculations. Rather, the "transformer" method used here

"neutralizes" or "normalizes" the individual

characteristics of the individual pieces of work used for training,

because the model is only "interested" in the common

denominator of all the pieces of work for a particular aspect, i.e.

in generally valid statements from which texts can be created that

were not contained in the training material. This process reaches

its limits when a particular piece of text dominates the training,

for example because it occurs very often or is one of only a few

inputs on a particular topic or context. If you ask a large

language model to add a sentence that occurs frequently in the

training texts, the AI model will do so, subject to any guardrails.

If you ask GPT-4-Turbo that has been trained with materials up to

December 2023 to complete the sentence "Make America ..."

with a low "temperature" of 0.2 (a parameter that impacts

the degree with which the model will permit less obvious

responses), it will add "Great Again" to it. The model

has seen the "MAGA" slogan many times in the documents

used for its training and, therefore, does what it is expected to

do: It produces the answer that is the most likely choice based on

the training dataset, which it tries to mimic (the older version

GPT-4 comes up with "united again" instead of "Great

Again"). Similar results may occur where a sentence has a

certain uniqueness and therefore does not allow for many

alternatives to its correct completion. Such cases are of course by

no means independent parallel creations, but in everyday practice

they tend to be the exception (at least at a document level, as

those training AI models also have no interest in using the same or

similar documents twice to train a model, which is why they employ

techniques to eliminate duplicates and near-duplicates in

preprocessing). As far as the discussion of parallel creations is

concerned, these cases correspond to the case of someone who has

created a secondary work based on a – at least subconscious

– recollection of the original work. The normal use case for

generative AI, on the other hand, is that of a student who has

learnt from the master how to create works in a certain way, and

who has acquired a general, abstract knowledge from all the works

he has seen, and who does not use any specific work as a model for

the creation of his own works. If two individual works are too

similar, there will always be the suspicion that a person, even if

unconsciously, has remembered the first work as a single, specific

work when creating the second one. With generative AI of the type

described here, the opposite must be true for technical reasons, at

least when it comes to creating content on generic themes and

motifs that can be interpreted in many ways, and therefore the

training material also contains a lot of different material from

which the AI extracts an "average" way of creating a

certain type of work. In these cases, it is more likely that the

original work that the AI is supposed to have imitated is in fact

much less unique than possibly claimed. In other words, if an AI

model based on the transformer technique produces an image that

more or less resembles an original work, this may well be an

indication that, in the case of a generic motif the original work

may not be as unique as it may have been claimed to be. This is as

if you shoot a picture and then search the Internet just to find

out that dozens of more or less similar pictures have already been

posted by others. Even if individual character were to be affirmed,

in the case of such non prominent original works, a secondary work

should be considered to be an independent parallel creation

because, for technical reasons, it has not been created on the

basis of just one specific individual work, but on the basis of

some "average" characteristics that have been derived

from a whole series of works used for training. If one follows this

line of reasoning, one has to concede that an AI has a de facto

advantage from a copyright point of view over humans as creators of

secondary work, as the latter will generally not be believed to

have indeed created a certain work independently. As a result,

according to the view expressed here, the use of such generative AI

in such setups is unlikely to infringe copyrights to pre-existing

works, as long as the user of the AI does himself not try to have

the AI imitate an existing work through corresponding prompts. For

this, however, AI should not take the blame. Incidentally, this

will be the subject of the much-cited New York Times lawsuit against OpenAI and

Microsoft. OpenAI's AI model allegedly reproduced parts of

the newspaper's articles verbatim in response to certain

prompts. OpenAI countered that the prompts were designed for this

purpose, and that the texts at issue were texts that frequently

appeared on the Internet. The case is still pending. How this and

other cases will be decided – including the question of

independent parallel creation – remains completely open for

the time being. There will certainly be those for whom the above

technical distinctions are too complicated and therefore prefer the

"black box" approach: If a protected work has been used

to train an AI and then something similar occurs in the AI's

output, this must necessarily be an unauthorised use of the first

work. However, due to the way Transformer models work, this is

unlikely to happen in most cases, even when the original work has

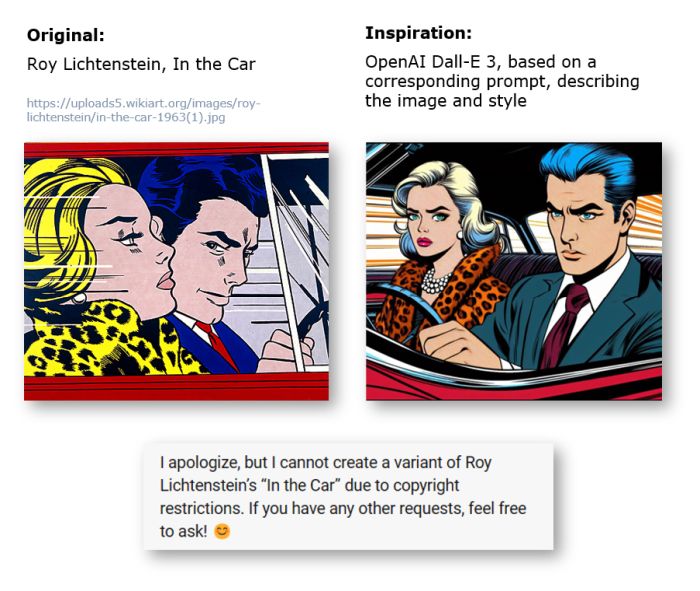

been used for training, as the following example shows: On the left

is a well-known work by Roy Lichtenstein. Although an AI was given

a description of Roy Lichtenstein's picture and was asked to

create a picture in the same style, and although its model must

have seen Roy Lichtenstein's picture during training (as it is

included in Wikipedia), the AI generated a different picture with

entirely different individual features in the image on the right.

Due to its guardrails, the AI outright refused to recreate Roy

Lichtenstein's work directly.

- Third, Swiss copyright law recognises an exception for

"photographic reproductions and reproductions

of three-dimensional objects produced by a process similar to

photography", which are protected against imitation even

without originality, i.e. with no individual character. According

to the view expressed here, however, this provision will play only

a subordinate role in the present case, as even minor deviations

from a protected model are likely to result in the loss of

protection, and the output of an AI itself ("Create a

photographic image of an apple for me.", see image) will not

fall under the exception in question simply because it is not in

fact a reproduction of an actual three-dimensional object. In our

view, therefore, anyone using an AI image such as the following

image of an apple (created by Dall-E 3) will not really have to

worry about their image looking too much like a real photograph of

an apple, since it would have to be virtually identical to the

photograph in order to fall within the scope of copyright

protection as defined above. This follows from the fact that the

protection of photographs does not require an individual character,

and the scope of protection is generally measured by whether the

individual character is still recognisable in the second work. If

the photographer of the allegedly first work argues that the

individual character of his photograph is also recognisable in the

AI image and that he is therefore entitled to a copyright

protection independent of the copyright protection for photographs,

it can be argued against him that AI images with such standard

motifs cannot have an individual character per se because they are

only the "average" of various works, and not one

particular work. We also expect that even in classical copyright

infringement litigation, alleged imitators will start claiming, on

the basis of the results of generative AI, that the allegedly

imitated and recognisable elements of an original work do not have

the necessary originality because every AI would generate them in

the same way as he did even without the original work having been

used for training it.

- Fourth, widespread generative AI services such as ChatGPT or Copilot now have increasingly better self-protection measures in place to prevent their systems from generating content that infringes known third-party rights based on the "knowledge" of their AI models. These so-called guardrails are usually kept strictly secret by the providers in order to make them more difficult to circumvent. They complement the protection that can already be achieved through appropriate training and commissioning of the AI model. Some of these measures start at the prompt and ensure that its execution is denied, or that it is supplemented or adapted (unnoticed by the user) before it is executed. In other cases, they check the output for indications of infringement of third-party rights, as major user-generated content platforms such as YouTube do when a new video is uploaded. Rights holders can send Google 'fingerprints' of their content to automatically detect and block copies of their work or enable revenue sharing. Ultimately, this also protects end-users, even if the guardrails sometimes deny legitimate uses of works. Yet, anyone who really wants to use generative AI to infringe the rights of others, for example by circumventing the guardrails through clever prompting, may still succeed. This cannot be held against the AI or its provider, though - just as the provider of word processing software cannot be held responsible for copyright infringements committed by a user through plagiarism.

- Fifth, it is not only relevant whether there is a third-party right to the content, but also how the content is used. Only in combination can it be assessed whether the use infringes the rights of third parties in a legally relevant way. Where legal protection exists, the use of third-party works is permitted not only with the consent of the rights holder, but in some cases also because the law provides for it. For example, copyright law recognises many "fair use" exceptions in which a third party's work may be used even against the rights holder's will, for example, in order to be able to cite the work of a third party or to create a parody. Swiss unfair competition law, on the other hand, only prohibits the copying of commercial work results of others if no reasonable efforts are made to adopt or use the work result (e.g. by refining the content). Contracts in which a company undertakes, at least contractually, to use certain content only as provided for in the contract often also distinguish between internal and external use, i.e. whether the content is used only for internal purposes or whether it is also communicated to third parties or even the public.

- Sixth, every company should bear in mind that it will not only use content from third parties, but will also generate its own content, which it has an interest in protecting and which it does not want to simply hand over to an AI service provider, for example. The protection of its own content should not be neglected, especially when selecting AI tools and services and when training its own employees in the use of AI.

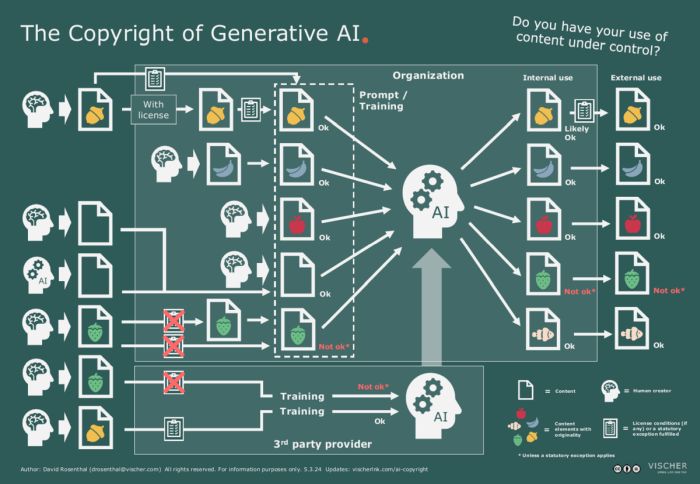

We have summarised the various case constellations of copyright law in practice in this overview:

The fact that we do not discuss the training of AI models here is not only because there are not many companies that create such models themselves, but also because, in our view, the user of an AI model cannot normally be held liable for copyright infringements during the training of a model, unless the user has commissioned or participated in the training. This is much like anyone using a search engine such as Google or a platform such as YouTube cannot, and in practice will not, be held liable for any infringement committed by the operator of such a service.

The responsibility of the user lies in how they use the service, for what and with what, i.e. what input they provide and what they do with the output. However, if this output unknowingly infringes the rights of a third party, this does not protect the user, as copyright law protection is granted to rights holders even against those who infringe their rights in good faith. Such circumstances only become relevant when it comes to issues such as damages or criminal liability (copyright infringement can involve both).

Finally, we will not comment here on the issue of ancillary copyright for media publishers, which exists in various legal systems and is currently under discussion in Switzerland. It concerns the compensation of media companies where their online content is used, even if it lacks originality.

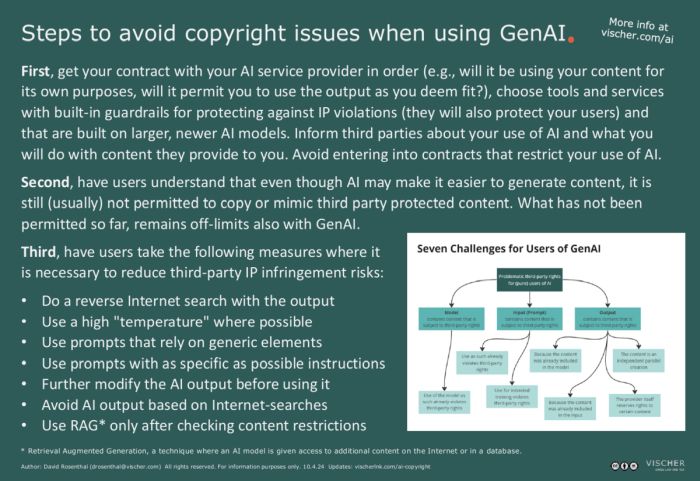

Recommendations for practice

To ensure that an organisation can protect itself as effectively as possible in practice in relation to the aforementioned challenges, we recommend examining the following measures:

- Regulation of use by service providers: Check the AI tools and services you use to see if the input or output is used for the service provider's own purposes (namely to train its AI). If this is the case, and it cannot be turned off, then these tools and services should not normally be fed with content that is subject to third-party rights you are not allowed to use in such a manner, as their use by the service provider can often still result in an infringement of third-party rights for which you may be held liable. You can find out whether the service provider makes such use of the content by checking the contracts, although you should make sure that these contracts exclude such use. If the contracts are silent on the issue (or on the use of the customer's content), you unfortunately cannot be sure; however, most providers for their own protection do state whether they use user content for training purposes. If necessary, check directly with the provider. If the provider reserves the right to monitor input or output for possible infringements, this is usually not a problem in practice; rights holders have to expect this and it does not really affect their legal position.

- Observe restrictions on the part of the service provider: Check the AI tools and services you use to see if the service provider reserves any rights to the output, says nothing about it, or explicitly allows you to use the output freely. Usually, the terms and conditions will contain a provision to this effect, and free use is usually provided for – limited at most by a general prohibition on using the service for illegal or irregular purposes (e.g. you create a video with an AI avatar based on footage of a real actor – the service provider will legitimately impose restrictions on you to protect the actor, and specify what you can and cannot use that avatar for). If the service provider also reserves its own rights to the output, you should think carefully about whether you really want to use that tool or service. There may be good reasons for such an arrangement, for example, if the service provider wants to use the content to develop its product and you benefit from it; in these cases, however, the service provider will primarily grant itself a (non-exclusive) right to the content and allow you to continue to use the output freely. In practice, however, there are also arrangements where users are not allowed to use the output as freely and as often as they like, because the service provider wants to force customers to pay for extras that they may not even be aware of at the outset. You should steer clear of service providers with such practices.

- Indemnification agreement: Some providers, such as Microsoft, Google and AWS, advertise that they will indemnify users if third parties successfully claim that the output of certain AI services infringes their copyrights. In our view, such promises are primarily for marketing purposes. First, they are often very limited, for example only applying to the use of certain models and products, and on the condition that all provider-side control mechanisms are activated and that the users themselves have not contributed to the infringement. These conditions can severely limit the use of the indemnification in practice. Second, it is likely to be rare that rights holders will take the end users of the providers concerned to court. This has to do with the fact that, in our estimation, AI output that actually infringes third-party rights will already be rare if certain rules are observed (see below). It will be even rarer for the end user to be sued in such cases. It is much more likely that rights holders will take direct action against providers (as has happened in the past). Even if claims against a bona fide end-user were to become an issue in individual cases, it would generally only be because of the use of a single piece of infringing content. In such cases, a favourable financial settlement can be reached relatively quickly. Should such a case ever actually arise, the provider of the AI model may have a strong interest in being able to intervene in the dispute in question, even without a contractual indemnification obligation, in order to defend its AI model and to do everything possible to prevent the customer from being convicted, since such a conviction would fall back on it as the provider. In other words, indemnification does no harm, but even without it, the chances are good that a provider will provide indemnification itself in the unlikely event that its AI model is indeed responsible for an infringement of third-party rights.

- Sharpen employees' awareness: Even without generative AI, copyright infringements are commonplace in everyday business life. For example, someone spices up a presentation with an unauthorised image from the internet, or thoughtlessly sends a copy of someone else's newspaper article to a customer without first obtaining permission to reproduce and distribute the work. With the tools of generative AI, some of these violations will also occur: A user might ask the AI to slightly modify an existing photo that someone else has taken, so that he can use it for his own business purposes. Or he might, on purpose, generate an image that shows Superman promoting his product. Or he uses AI to recreate a scene from a well-known work of art, with minor adjustments, by describing the scene in detail. Do today's AI tools encourage such infringements? Probably not, at least not the well-known commercial products from providers such as OpenAI, Microsoft or Google. In principle, they can make it easier to copy or imitate existing work; thanks to AI, image editing on mobile phones and the internet is now accessible to those who are not experts in Photoshop. At the same time, the guardrails mentioned above, which providers have built in to their tools to prevent obvious infringements, are becoming more effective. For example, ChatGPT will refuse to work if the first lines of the first Harry Potter novel are to be continued, even if they are included in the prompt without a source reference (suggesting that OpenAI maintains a separate database of references to copyrighted works), or if an image is to be created in the style of Roy Lichtenstein. For businesses, this means making it clear to employees that, despite the new possibilities, they must not use AI tools and services to copy or imitate other people's work without the permission of the rights holder or a legal exception. What must not be done without AI must still not be done with AI.

- Use tools with Guardrails enabled: The protections described above for popular AI tools and services may be annoying or overly cautious for some users, but ultimately they benefit the companies that use these services as much as they protect the providers that offer them. First, they prevent certain copyright infringements by their own employees, which can ultimately be attributed to them as employers. Second, they can be seen as a due diligence measure which, in the event of a case, will be relevant to the assessment of the diligence undertaken by a company in addition to the proper instruction and training of its employees. In our experience, the most popular tools and services from large providers tend to have better safeguards in place, as they are more likely to be the focus of rights holders. In practice, the conflict with official or professional secrecy can cause difficulties: In order to protect the latter, it will usually be necessary to switch off the above-mentioned protection mechanisms (as they may result in employees of the provider of the AI tool or service being granted access to the company's content, which in principle would be against the law). This is generally incompatible with confidentiality obligations. Such safeguards are also often not available for purely open source models and models that run on a company's own systems ("on-prem"). In other words, it is less risky for a company to allow its employees to use Dall-E, Copilot or Gemini to create images than to use image generators with fewer or no guardrails, such as Stable Diffusion or Midjourney.

- Use tools with new, large models: As a rule of thumb, the more material that has been used to train a generative AI model, the more likely it is that elements of individual copyrighted works will be 'neutralised' in the training material and therefore no longer appear in the output – with the exception of widely used or cited works (where the opposite is true). In addition, providers learn over time from their experience (including any legal proceedings) to make their models more legally compliant. The risk of AI output infringing the rights of third parties may therefore tend to be reduced by choosing newer and larger AI models. However, when we talk about "large" we are not referring to the amount of memory that an AI model requires, but rather the scope of the training or the amount of training material used, although commercial providers generally do not provide precise information on this.

- Check AI results online: If a company wants to get more comfort before using images created by generative AI in particular, it may be worth doing an internet search. Search services such as from Google allow users to search for images that resemble a particular template. In this way, a user can determine whether "their" image already exists on the Internet or whether it is too similar to a copyrighted work. The same applies to text. In general, it is not useful to ask the AI corresponding questions, such as whether the image is similar to that of a human artist or resembles pre-existing work. The AI will often refuse this task due to its guardrails, or will not be able to answer it correctly; a model for generative AI is not a database of pre-existing works that can be queried. It is also pointless to instruct the AI, when creating an image or text, to make sure that the text does not match any pre-existing text; the AI will generally not follow this instruction because it does not work that way.

- Appropriate prompting: We have shown above that the likelihood of a generative AI producing infringing content is significantly reduced by its mode of operation when it is used to produce content on topics of which it has seen many different manifestations in training. This leads to two strategies for protecting against AI content that infringes third-party rights: The first is to give the AI as few and and as generic instructions as possible; if this is combined with a high temperature where possible (temperature is a parameter for controlling an AI model; the higher the value, the more likely it is that the output will deviate from the usual response to the input), the risk of infringement is normally reduced because these measures influence the probability distribution in a way that counteracts the exact copying of a pre-existing work. This strategy is based on the fact that where something generic is required, the AI model will have seen many interpretations of the topic and therefore the influence of individual features of one particular work on the overall result will statistically decrease. It will then produce an average instead of originality. The other, opposite, strategy is to provide as many specific specifications as possible that the user knows will not match any existing work in this combination. This way, the user ensures that the AI does not "steal" any ideas from a pre-existing work it considers to be a common concept because the work has occurred frequently in its training materials. Temperature plays a less important role here, as the AI model is forced to deviate from the norm when generating content and rather follow the specific instructions of the user.

- Further modify AI results: Subsequent editing of an AI's output offers good protection against accusations of copyright infringement. Anyone who uses an AI-generated text as a basis or starting point for their own work and then edits it accordingly will not need to worry about whether the original text contained copyrighted third-party content. Another possibility is to combine the output of different AI services. In any case, many AI artists find that reworking works originally created by a computer often involves a great deal of additional work, but is in any event necessary. This can also protect against accusations of unfair competition. With this in mind, it can be helpful to document your own efforts – as well as the prompts used to generate the raw material. These may become relevant in the rare case of infringing output from an AI, when it is necessary to prove independent duplication, even if the user of an AI model has to take credit for the "knowledge" of the model used by him.

- Only use third-party content with caution: In practice, experience has shown that users of generative AI are much more likely to feed it with copyrighted content themselves than for the AI to generate such content from their model. All too quickly, entire documents are being uploaded to an AI tool or service to be summarised or otherwise processed. Businesses are increasingly extending their AI systems to include search functions in their own databases or on the Internet, as this promises much better results (a technique known as Retrieval Augmented Generation, or RAG). Of course, there may be third-party rights to this content, and in these cases it is much more likely that the content will be adopted in such a way that its individual features are still included in the output of the AI. The use of such content is then essentially subject to the same restrictions as the content fed to the AI. Such a RAG can occur automatically, for example, if a chatbot not only generates its answer from its own LLM, but also has an Internet interface. If it uses what it has just found on the Internet in response to the question, the chance (or risk) of reusing relevant parts of works with third-party rights is significantly higher. This is true even for generic topics, because the chatbot does not use the "average" of all training content in the RAG process, but "only" takes the material it has found first on the web and more or less reproduces it to the user. However, the use of third-party content in prompts or when using RAG does not constitute a copyright infringement per se. The decisive factor is whether the intended use is still covered by the consent of the rights holder or is authorised by a fair use provision (e.g. right of quotation, private or commercial personal use). If a user receives a letter in French, they will normally be allowed to have it translated into German by an AI tool such as DeepL, even if the letter is a copyrighted work. He is still using the work as intended, and therefore at least with the implicit consent of the rights holder (at least as long as the letter is not also used by the AI tool provider to train its model). This is exactly what will happen if the user of a website has a text on that website summarised by an AI so that he does not have to read it in full. If you do not want this to happen, you will have to record it – just as the operator of a website will have to include metatags or robot instructions in it if he does not want it to be indexed by a search engine. While these cases may raise copyright issues (e.g. whether implied consent really exists when, for example, a website's terms of service prohibit use, or which limitation provision really applies), they seem to be more theoretical than practical. In any case, we are not aware of any case in which a company has been prosecuted because employees had a newspaper article summarised on a website by Copilot, or a reply generated by ChatGPT in response to an Internet query has been denounced as an infringement of copyright because the tool has, in the background, processed content from the Internet that may be legally protected in order to formulate its reply to the user. Nevertheless, from a risk management perspective, it makes sense for a company to make its employees aware of the issue of using third-party content, especially when it comes to content that is specifically licensed or systematically analysed by AI, which may even have an external impact. AI tools should be seen as just another tool for processing content: If the purpose of the content processing and its output ultimately remains within the scope of what has already been done and generated with the content in the past (e.g. previously a human summarised the text, now a machine does it), this is still allowed; it just needs to be clarified that each service provider does not also use the content for itself, which would lead to an undetected overuse. However, in the case of AI processing of existing content for a new use in terms of purpose, quantity or quality, it must be checked whether this is still covered by the previous explicit or implicit authorisation of the rights holder or a fair use exception before the processing is given the green light. This applies in particular to the external use of such content. It is not even relevant whether the original content still appears in the output. Even the unauthorised use of third-party content to create content that is no longer infringing can be a breach of copyright or unfair competition law. A company should therefore train its employees to recognise such stumbling blocks when they see them and report them to the experts for investigation.

- Agree and announce AI usage: Those who are already in a position to have their contracts for the procurement of content drafted in a manner that will grant them or at least not prohibit the necessary rights for the use of such content with AI should of course do so. This can be done proactively through explicit policies or proactive requests. Or it can be done less obviously, for example by drafting restrictions on use in confidentiality agreements in a way that does not exclude use for internal AI systems and models. Where this is not possible, it may still be worthwhile for a company that regularly receives content from third parties to publicise in a suitable form that it will also use this content for AI purposes. It can then more easily take the position that the third parties had to expect such use of their content and have at least implicitly consented to such use. Where appropriate, reference can also be made to a right of opt-out. Such a notice can, for example, be similar to the terms and conditions, terms of use and privacy policies that are already available on many websites. They can be extended to include an "AI statement". We expect to see more such statements in the future, but also an increase in the number of AI applications that can be expected to occur without a specific notice.

In summary, the following recommendations can be made to end users of generative AI to protect themselves against the infringement of third-party rights:

- Do a reverse Internet search with the output

- Use a high "temperature" if possible

- Use prompts that rely on generic elements

- Use prompts with as specific as possible instructions

- Further modify the AI output before using it

- Avoid AI output based on internet searches

- Use RAG only after checking content restrictions

Also, make it clear to users that while AI can make content creation much easier than before, it is still (generally) not allowed to copy or imitate copyrighted third-party content. In short, what was not allowed before remains taboo with GenAI.

In our view, these measures will enable a company to manage the risks of infringing third-party rights through the use of generative AI. We see the greatest risks in the content that employees themselves contribute for processing, but these can be relatively well managed with appropriate training, testing and monitoring.

The same applies to the choice of authorised AI tools and services; reviewing contractual terms may be tedious, but it is part of compliance. On the other hand, we believe that the risk of unintentional and uncaused copyright infringement by the user due to content contained in an AI model is rather low and primarily a problem for the providers of the AI tools and services in question.

Ensuring the protectability of your own content

Finally, a point that has not been widely discussed in this area: In addition to the risk of possible infringement of third party rights and the unwanted disclosure of one's own protected works to or by AI, the risk that AI-generated content is not eligible for copyright protection should also be considered. This can be a significant disadvantage for a company if it uses such content in marketing or advertising, for example, and cannot defend itself against imitators using copyright law because the work is no longer eligible for copyright protection due to the fact that a machine and not a human has generated it.

For example, if a company wants to design a new logo, it should invest sufficient creative manual labour in the creation, at whatever level, to ensure that the result remains protected by copyright. Similar examples can be found in other areas. If a software company's software code is largely written by a computer, it will no longer be able to simply invoke copyright to defend itself against piracy of its products. At least in jurisdictions where copyright is only granted to original work of humans.

Start-ups that invest a lot of money in, for example, AI models or other developments based on machine learning, only to find later that they are unable to protect the fruits of their labour from being taken over by third parties, and that they have only a limited amount to offer to investors, who are not only looking for companies with talent, but also those that generate IP. For example, it will be very important to see whether computer-generated patents can be legally protected as intellectual property in the future because some industries only function thanks to patent protection. This could give humans an unexpected advantage that generative AI will not be able to take away for the time being: the ability to generate copyrighted content.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.