![]() and

Audrey J. Diamant

and

Audrey J. Diamant ![]()

The Goods and Services Tax (GST) was introduced more than 20 years ago, but many trips and traps continue to catch business operators. This article discusses some issues that often affect privately owned businesses.

Management/ Intercompany fees

It is common for several corporate entities to be established within a group. This can be to:

- maximize tax planning opportunities;

- shelter particularly valuable business assets in a separate entity for creditor-proofing purposes; or

- centralize all administrative functions in one corporation and have it provide services to other members in the corporate group.

Management and other intercompany fees may then be charged between members of the corporate group. These fees are generally taxable for GST/HST purposes, a fact that is often overlooked, particularly if the fees are simply booked by way of journal entry instead of issuing formal invoices. As a result, the company receiving the fees can be assessed for failure to collect GST/HST. Conversely, if GST/HST is charged, failure to provide adequate documentation to the entity paying the tax can result in denial of the input tax credits (ITCs) claimed.

In some cases, if the corporations are closely related for GST/HST purposes, it may be possible to make a special election to avoid having to charge GST/HST on the intercompany fees. Two companies are closely related if, for example, 90% or more of the value and number of the issued and outstanding voting shares of one company are owned by the other company, or by a company that owns 90% or more of the issued and outstanding shares of both companies. If the 90% threshold is met at all levels, a corporate parent of a company can be closely related to a subsidiary of that company. Several years ago, the definition of "closely related" was expanded to include Canadian partnerships.

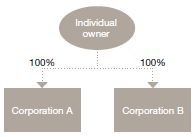

However when an individual owns all of the shares of corporation A and B (see diagram below), this election cannot be made, because for GST/HST purposes Corporation A is not closely related to Corporation B.

However, if the individual owner transferred his or her shares of Corporation A and B to a Holdco (see diagram below), it would open the possibility of a joint election between Corporation A and Corporation B to avoid having to charge GST/HST. One of several other conditions to be met before an election can be made is that 90% or more of the property owned by each of the parties to the election must have been acquired for consumption, use or supply in commercial (i.e., GST-taxable) activities. If a party has no property at the time of the election, 90% or more of its revenues must be GST-taxable.

Place of supply rules

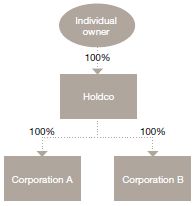

Canada is unusual in having a value added tax system that imposes rates of tax that vary with geographical location, as indicated in the table below. Total effective rates range from 5% to 15.5%.

To determine which rate of tax to collect, suppliers must use provincial place of supply rules in the GST/HST legislation or regulations.

For example, in the case of a sale of goods, the rate of tax depends upon the place of delivery. A supplier that has arranged for the carrier to ship the goods to a customer in a particular province is deemed to have delivered them in that province. Therefore, a supplier in Calgary that ships goods to a customer based in Vancouver is required to collect the 12% HST applicable in British Columbia and not the 5% GST that applies in Alberta.

When the HST was introduced in Ontario and British Columbia on July 1, 2010, the place of supply rules for some services and intangible personal property were changed. As a result, companies providing services that are not in relation to real or tangible personal property are generally required to collect GST/HST according to the address of their Canadian customer rather than where the services are provided. However, for some services, such as sales solicitation provided to registered non-residents, that sell goods for delivery in Canada, the tax may still be determined by the location where the services are provided.

Naturally, using the wrong place of supply rule can result in charging the wrong amount of tax.

Zero-rating of goods and services

Most GST/HST registrants know that GST/HST is not collected on goods that are exported. Even if the goods are delivered to the customer in Canada, the sale of the goods can be zero-rated, meaning no tax has to be collected by the supplier, if all of the following conditions are fulfilled:

- the purchaser exports the property as soon after the property is delivered as is reasonable having regard to the circumstances of the exportation and the normal business practice of the purchaser;

- the purchaser does not acquire the property for consumption, use or supply in Canada before exporting it;

- after the supply is made and before the purchaser exports the property, the property is not further processed, transformed or altered in Canada, except to the extent reasonably necessary or incidental to its transportation; and

- the supplier maintains evidence satisfactory to the Minister of Revenue of the exportation of the property by the purchaser.

Many services to non-residents can be zero-rated, but not those in respect of real property or tangible personal property situated in Canada. Some services, such as advertising, cannot be zero-rated if the non-resident is registered for the GST/HST.

Therefore, care must be taken in dealing with non-residents to ensure that all required conditions for zero-rating are met before deciding not to charge GST/HST.

Drop shipment rules

When goods are sold to unregistered non-residents, or services are performed in respect of goods they own, drop shipment rules apply. Sometimes these are punitive, but they can also provide relief. Two situations illustrate how the drop shipment rules can be punitive.

A Canadian supplier sells goods to an unregistered non-resident and delivers (drop ships) those goods to the non-resident's customer in Canada. To avoid having to collect GST/HST on the sale of the goods, the Canadian supplier must obtain a drop shipment certificate from the Canadian customer to whom the goods are delivered. The Canadian customer cannot be an individual who is purchasing the goods for personal consumption.

If the Canadian supplier does not obtain a drop shipment certificate, the GST/HST legislation requires it to collect the appropriate rate of GST/HST (see the place of supply discussion above) not on its selling price to the unregistered non-resident but on the fair market value of the goods (presumably the non-resident's selling price to the Canadian customer).

These drop shipment rules can be even more punitive if the Canadian supplier is simply providing a service in respect of goods owned by the unregistered non-resident. Consider a Canadian company that stores, in Canada, goods owned by an unregistered non-resident, and then ships them to the non-resident's customers in Canada. This situation is illustrated below.

Assume that the Canadian supplier invoices the unregistered non-resident $20 for the services and the unregistered non-resident invoices its Canadian customer $100. The drop shipment rules deem a Canadian supplier that lacks a drop shipment certificate, to have made no supply of services to the non-resident, but instead to have sold goods to the non-resident for $100, on which the GST/ HST must be collected. In this case, the amount of tax to be collected could exceed the charge for the services.

De minimis financial institution rules

Under the GST/HST, many holding companies in a corporate group are deemed to be financial institutions. If that happens, among other things, the company must:

- allocate some of the GST/HST paid on expenditures incurred to hold investments, resulting in a loss of ITCs;

- file a special GST/HST return (form GST 111); and

- track changes in use of capital property between taxable and exempt uses more closely.

A company becomes a financial institution for GST/HST purposes if:

- the total of its income from interest or dividends from

non-related corporations and separate fees for a financial service

in the previous year exceeds both:

- 10% of its total revenues other than sales of capital property in that preceding year; and

- $10 million dollars prorated for any taxation year shorter than 365 days; or

- the total of its income in the previous year that is interest or a separate fee or charge, with respect to a credit or charge card issued by the company or the making of an advance, the lending of money or the granting of credit, is over $1 million. The $1 million threshold is prorated for taxation years shorter than 365 days.

Input tax credit documentation

The GST/HST legislation requires a purchaser to obtain certain prescribed information from the supplier before an input tax credit can be claimed. For purchases of $150 or more, the purchaser is required to obtain written documentation of the following information:

- name of the supplier;

- date of the invoice;

- total amount paid or payable for the supplies;

- GST/HST registration number of the supplier;

- total amount of the tax charged or a statement that the total price includes the tax;

- purchaser's name;

- terms of payment; and

- descriptions of each supply sufficient to identify them.

GST/HST auditors routinely check to see that a purchaser has this information on file. If insufficient documentation is found, the input tax credit claimed will be denied. The Canada Revenue Agency has a website on which the GST registration number of the supplier can be verified (http://www.cra-arc.gc.ca/esrvc-srvce/tx/bsnss/gsthstrgstry/menu-eng.html) Purchasers should check this website regularly, particularly in the case of larger purchases, to ensure they have been given the correct GST number.

Recaptured input tax credits

When the HST was introduced in the provinces of Ontario and British Columbia on July 1, 2010, large businesses (those with more than $10 million in annual taxable Canadian sales on an associated group basis) were required to recapture (i.e. repay) the provincial portion of the HST on certain expenditures. These expenditures include the following:

- most telecommunication charges;

- meals and entertainment expenses subject to the 50% restriction on income tax deductibility;

- energy sources other than that used directly in the production of goods for sale or primarily in farming activities of a person whose chief source of income is farming;

- motor vehicles licensed for highway use and weighing less than 3,000 kilograms; and

- fuel (other than diesel) for use in those vehicles.

The recaptured amounts must be reported separately on Schedule B of the GST/HST Netfile return. Failure to do so can result in the imposition of penalties starting at 5% of the amount that should have been reported and increasing each month. Therefore, a taxpayer cannot simply deny itself the provincial portion of the ITC rather, it must report both the total ITC and the recapture amounts separately.

Meals and entertainment expenses and input tax credit restrictions

For meals and entertainment (M&E) expenses that are subject to a 50% restriction on deductibility for income tax purposes, businesses that are not large businesses, as defined above, claim only 50% of the GST/HST paid as an ITC. The other 50% is considered to be a personal expenditure on which no credit can be claimed. This restriction is often missed and is one of the first items that a GST/ HST auditor will look for.

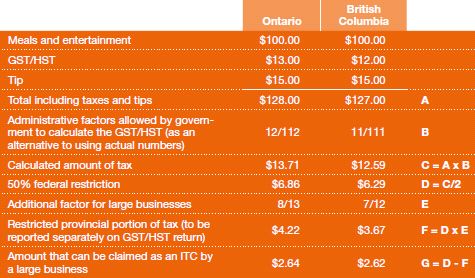

For large businesses, there is a further restriction in that they are required to recapture the provincial portion of the HST in Ontario and British Columba on M&E (see previous discussion), which means that only a small portion of the HST paid can be recovered. The following example illustrates the calculation:

GST on taxable benefits

Many GST/HST-registered companies provide taxable benefits to

their employees. The most common example is the use of

company-provided automobiles. (PwC has a helpful publication on

this topic: Car expenses and benefits − A tax guide

(2012), at

www.pwc.com/ca/carexpenses).

These companies may be required to repay a portion of the ITCs they previously claimed on expenditures to provide these benefits. This repayment must be included on the GST/HST return for the period in which the last day of February in the following calendar year (the filing deadline for T4s) falls.

While the actual calculation details are beyond the scope of this article, it is common for these calculations to be overlooked entirely or done incorrectly. GST/HST auditors often look at the taxable benefits that were calculated for income tax purposes to determine if a GST/HST liability exists.

Avoiding GST/HST problems

After twenty years, GST/HST can still cause problems for privately owned businesses. A review by PwC 's sales tax professionals of your company's compliance can help identify and resolve them.

This article appeared in Wealth and tax matters for individuals and private companies, 2012, Issue 2.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.