- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

- in Canada

- with readers working within the Accounting & Consultancy, Banking & Credit and Business & Consumer Services industries

As most readers know, in a bit of a surprise announcement the 2019 Federal Budget announced changes to the existing taxation treatment of employee stock option benefits to fully tax certain benefits. Currently employee stock options receive preferential taxation treatment (which results in most employee stock option benefits being treated in a capital gains-like fashion and thus being only ½ taxable). Our firm's report on this proposed change earlier this year can be reviewed here.

The budget announcement lacked significant detail but promised to release additional details before the summer. In true form, this promise was met 4 days before the official start of summer when the Department of Finance released a Notice of Ways and Means Motion on June 17, 2019 that contained draft legislation and a "Backgrounder" to help explain the draft legislation. As part of its announcement, the Department of Finance announced that it would like to receive input regarding the characteristics of employers that should be exempt from the proposed changes, with a due date for submissions of September 16, 2019.

In order to provide context about this important topic – rather than just "reading the news" – this blog will quickly review the history of the taxation of Canadian employee stock options, and briefly review the historical policy reasons why employee stock options have been preferentially taxed. With this context, the proposed changes can then be better understood and evaluated.

A. Executive Summary

For those who do not have the patience to read all of the comments below, here is a quick executive summary:

- Tax preferred taxation for employee stock options has been provided for in the Canadian Income Tax Act since 1953, with a bit of a pause between 1972-1976, and then reintroduced for the period from 1977 to current day;

- The historical policy reasons for tax preferred treatment has historically been to assist with competitiveness issues, to quell the "brain drain" to the United States and to assist smaller businesses with their ability to attract skilled labor while maintaining working capital;

- In 2015, the federal Liberal Party campaigned and promised to reduce the employee stock option taxation preference. Once elected however, they did not implement this promise;

- The 2019 Federal Budget resurrected the Liberals' election promise with this proposal to eliminate some of the tax preferences for employee stock options. The budget material lacked significant detail, but promised that employees with up to $200,000 in annual stock option benefits would be unaffected by any new change;

- On June 17, 2019, the Department of Finance released more detail on how it intends to modify the taxation treatment for certain companies, with some details still missing. It is intended that the new regime will take effect January 1, 2020 for options granted on or after that date;

- It is doubtful that the new rules will become law until after the federal election which will take place on October 21, 2019, so it appears the Liberal government is planning to recycle outstanding campaign promises from the 2015 election;

- The policy reason stated for the proposed changes is debatable and in my view the government needs to improve the transparency for such change; and

- Affected and interested parties should quickly get up to speed on the proposed changes and adjust compensation planning accordingly.

B. The Historical Canadian Taxation Treatment of Employee Stock Options

In an excellent Canadian Tax Journal article1 written by Professor Daniel Sandler and published in 2001, Professor Sandler provides a good summary of the historical Canadian tax treatment of employee stock options. Prior to 1948 – with no explicit provision in the Income Tax Act – it appears that benefits realized from employee stock options were accorded capital gains treatment (and thus not taxable since Canada did not tax capital gains prior to 1972). From 1948-1953, employee stock option benefits were treated as normal employment income. In 1953, legislation was introduced to grant preferential tax treatment to the benefits associated with employee stock options. This included taxing any benefit upon the exercise of the option (rather than on the date of the grant), and providing preferential tax rates for the resulting benefit.

In 1972, (as a result of significant tax reform implemented after the Royal Commission on Taxation tabled its report in 1966, and numerous related debates and studies), the preferential tax treatment of employee stock option benefits ended. While the timing aspect of the benefit remained (the benefit was only taxable when the stock option was exercised and not on the date of grant), the employee was no longer accorded preferential rates, or reduced income inclusions on the date of exercise. The required income inclusion was equal to the fair market value ("FMV") of the underlying stock acquired as a result of the option exercise minus the amount paid to exercise such option. In all instances, the employer was not granted a corporate deduction as a result of the exercise of the employee stock options.

In 1977 preferential tax treatment was re-introduced into the Act by legislating a deferral for stock option benefits that were realized on the date of exercise for employees of Canadian-controlled private corporations ("CCPCs") so that the benefits were taxed upon the disposition of the underlying shares. Additionally, if the underlying shares were held for 2 years, then any resulting benefit was treated as a capital gain. If the shares were held for less than 2 years, the entire amount would be treated as employment income. As Professor Sandler relates in his 2001 article, the Minister of Finance in 1977 explained the rationale for such preferred tax treatment as follows:

"According to the Minister of Finance Donald S. Macdonald,

[a] particular problem for small business is the difficulty of matching higher salaries offered by larger enterprises. I propose to introduce a special tax treatment for stock option plans established for employees of Canadian-controlled private corporations. The difference between the option price paid for the shares and their sale proceeds will be taxed as a capital gain and then only when the shares are disposed of. This will permit a company to reimburse its employees in a way that does not impair its working capital."

The changes above were ultimately enshrined into Canadian tax law in subsection 7(1.1), with the nuts and bolts remaining today, as explained below.

In 1984, preferential tax treatment was also extended to option holders of non-CCPCs. Professor Sandler nicely summarizes the 1984 change as follows:

Preferential tax treatment spread to other stock options in the 1984 federal budget when paragraph 110(1)(d) was introduced. As a consequence, if a non- CCPC granted to arm's-length employees options to acquire qualifying equity shares and the exercise price was at least equal to the fair market value of the shares on the date the option was granted, the employee benefit was taxed at the same rate as a capital gain. The full benefit was included in income in the year the option was exercised, but under paragraph 110(1)(d), the employee was entitled to deduct an amount equal to 50 percent of the benefit provided that the preconditions for its application were met. According to the budget documents, the amendments were designed "[t]o encourage more widespread use of employee stock option plans which promote greater employee participation and increased productivity."

In 1985, as a result of the introduction of the capital gains deduction, subsection 7(1.1) – applicable to CCPC employee stock option benefits – was slightly amended and new paragraph 110(1)(d.1) was introduced. The amendments ultimately continued the deferred taxation of any benefit realized upon the exercise of CCPC stock options until the shares were disposed of. Upon disposition, the resulting benefit (computed from the exercise date) would be treated as employment income. Any further increase in value of the shares from the exercise date would be treated as a capital gain. New paragraph 110(1)(d.1) would enable a 50% deduction from the resulting employment income if the underlying shares were held for 2 years or more.

In the 2000 federal budget, in an apparent attempt to try to reduce the "brain drain" that was occurring with Canadian skilled labor departing to the United States, new complex rules were added into the Act that enabled certain non-CCPC employee stock option benefits – upon election – to be deferred2. As produced in Daniel Sandler's 2001 paper, the government rationale for introducing the new rules – as stated in the 2001 Federal Budget was as follows:

To assist corporations in attracting and retaining high-calibre workers and make our tax treatment of employee stock options more competitive with the United States, the budget proposes to allow employees to defer the income inclusion from exercising employee stock options for publicly listed shares until the disposition of the shares, subject to an annual $100,000 limit.... Employees disposing of such shares will be eligible to claim the stock option deduction in the year the benefit is included in income. The new rules will also apply to employee options to acquire units of a mutual fund trust. The proposed rules are generally similar to those for Incentive Stock Options in the United States.

As mentioned above, the amount of deferral was subject to an annual limit of $100,000 based on the year the options become exercisable, and on the value of the shares when the options were granted. Accordingly, this required very careful tracking of option agreements including the tracking of the vesting year, and which options were exercised from each agreement (if there were multiple option agreements with different grant dates and vesting years) to ensure compliance with the $100,000 annual limit. It was our firm's experience that these complex calculations were routinely computed incorrectly by taxpayers. These deferral rules were eliminated from the Act as a result of the 2010 federal budget.

While there have been other minor amendments since 2010, the above is an overly simplified history of the taxation of Canadian employee stock options.

C. So How Are Canadian Employee Stock Options Taxed Today?

To neatly summarize the above history, employee stock option benefits are currently taxed as follows:

1. Non-CCPC Stock Option Benefits

An employee is taxed on the date of the exercise of the option. The difference between the FMV of the underlying stock acquired and the amount paid – the strike price – is deemed to be employment income. As long as the strike price was at or higher than the FMV of the underlying stock at the date of grant, the employee will be able to deduct 50% of the employment benefit from his / her income. Any increase / decrease in value of the stock from the date of acquisition will be treated as a capital gain / capital loss respectively.

For example, consider the following example facts:

- Mr. Apple is an employee of OrangeCo – a publicly traded corporation.

- Mr. Apple is granted options on January 1, 2019 to acquire 100 shares of OrangeCo at a strike price of $10/share.

- The FMV of OrangeCo on January 1, 2019 is $10/share.

- The options vest on January 1, 2020.

If Mr. Apple exercises all of the OrangeCo options on May 1, 2020 at a time when the shares have a FMV of $110/ share, Mr. Apple will have the following taxable income impact:

- Taxable benefit on May 1, 2020 = FMV of underlying shares acquired minus strike price paid for shares: $11,000 – $1,000 = $10,000.

- Since the strike price was equal to the underlying FMV of OrangeCo's shares at the date of grant, Mr. Apple will be entitled to a 50% deduction under paragraph 110(1)(d) = 50% x $10,000 = $5,000.

- Therefore, Mr. Apple's net taxable income inclusion realized on May 1, 2020 = $5,000.

- The adjusted cost base ("ACB") of the 100 OrangeCo shares held by Mr. Apple would now be $11,000 – the FMV of the OrangeCo shares at the date of the exercise of the options.

2. CCPC Stock Options

Let's use the same facts as above, except now OrangeCo is a CCPC, and not a publicly traded corporation. In this case, Mr. Apple's taxable benefit is computed in exactly the same way but the benefit is automatically deferred until he disposes the underlying shares.

Let's now change some of the facts. Let's assume that the strike price to acquire the OrangeCo shares was $0.10/share but the FMV of the underlying shares on the date of the option grant was still $1/share. This means that Mr. Apple received options that were "in the money" by $0.90/share at the date of grant. We'll continue to assume that the FMV of the OrangeCo shares was still $110/share on the May 1, 2020 exercise date. Let's consider two scenarios:

a) Mr. Apple disposes of the OrangeCo shares on July 1, 2021 when the FMV of the OrangeCo shares is $150/share

In this scenario, Mr. Apple acquired the OrangeCo shares on May 1, 2020 but did not hold onto them for 2 years or more. Accordingly, Mr. Apple will compute his tax results as follows:

- Employee stock option benefit = FMV of underlying shares at date of acquisition less strike price: $11,000 – $10 = $10,990.

- Since the options were "in the money" and Mr. Apple did not hold onto the OrangeCo shares for 2 or more years, he will not be entitled to a 50% deduction under paragraph 110(1)(d.1) from the above computed amount.

- Mr. Apple's taxable capital gain will be computed as follows: proceeds less ACB (the FMV of the shares upon acquisition) = $15,000 – $11,000 = $4,000 x 50% = $2,000.

- Accordingly, Mr. Apple's net taxable income inclusion on July 1, 2021 = $10,990 + $2,000 = $12,990.

b) Mr. Apple disposes of the OrangeCo shares on July 1, 2022 when the FMV of the OrangeCo shares is $150/share

In this scenario, the only difference is that Mr. Apple has now held onto his shares for 2 years or more before he disposes of them. Accordingly he will be entitled to a 50% deduction under paragraph 110(1)(d.1) against his employee stock option taxable benefit realized on July 1, 2022 even though the options were issued "in the money". The above calculations for scenario a) are wholly relevant but now Mr. Apple will be able to deduct 50% of $10,990 = $5,495.

Accordingly, Mr. Apple's net taxable income inclusion on July 1, 2022 will be $10,990 – (50% x $10,990) + $2,000 = $7,495.

Note that in both above scenarios, the fact that the strike price is less than the FMV at the date of grant is irrelevant. For non-CCPC scenarios, "in the money" stock options always result in the employee losing the 50% deduction under paragraph 110(1)(d). For CCPC scenarios, employees can access the 50% deduction either through paragraph 110(1)(d) – options that are not issued "in the money", or through paragraph 110(1)(d.1) – holding the underlying shares for at least 2 years.

D. Should Employee Stock Options Be Subject to Preferential Tax Treatment?

Given the history of the taxation of employee stock options, one can obviously question the policy rationale for preferred taxation treatment. The stated policy objectives in 1977 was to assist small business in attracting talent when salaries paid at larger firms was higher, and thus assist in protecting smaller business's working capital. In 1984, the stated policy objective for the new preferred tax treatment was to encourage more widespread use of employee stock option plans to promote greater employee participation and increased productivity. And in 2000, the policy objective for the new deferral was to assist corporations in attracting and retaining high-calibre workers, and make the tax treatment of employee stock options more competitive with the United States. Very generally, in the United States, employee stock option benefits – with very limited exceptions – are treated as employment income inclusions with no preferred taxation treatment.

In his 2001 paper, Professor Sandler concludes his paper with the following statement:

In the absence of preferential tax treatment, employee stock options would still be included in compensation packages, provided there were sound business reasons for their use. The reasons given for their preferential tax treatment are not persuasive, and no evidence has been put forward that the use of stock options in the absence of tax incentives is suboptimal.

Professor Sandler's conclusion is not surprising given the title of his paper. There are certainly opposite points of view that suggest that the use of employee stock options – especially in start-up or smaller companies – can be a very useful tool to help incentivize employees and preserve cash / working capital for the company.

When introducing the new 2019 budget proposals and repeated upon the release of the draft legislation on June 17, 2019, the Department of Finance stated the following:

Employee stock options, which provide employees with the right to acquire shares of their employer at a designated price, are an alternative compensation method used by businesses to attract and engage employees, and encourage growth. Many smaller, growing companies, such as start-ups, do not have significant profits and may have challenges with cash flow, limiting their ability to provide adequate salaries to hire talented employees. Employee stock options can help these companies attract and retain talented employees by allowing them to provide a form of compensation that is linked to the future success of the company....

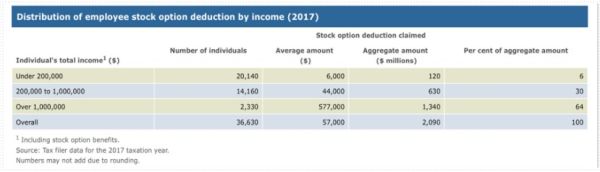

A review of employee stock option deduction claims reveals that the tax benefits of the employee stock option deduction disproportionately accrue to a very small number of high-income individuals – resulting in a tax treatment that unfairly benefits the wealthiest Canadians.

In 2017, 2,330 individuals, each with total annual incomes of over $1 million, claimed over $1.3 billion in employee stock option deductions. In total, these 2,330 individuals, representing 6 per cent of stock option claimants, accounted for almost two-thirds of the entire cost of the deduction to taxpayers.

The public policy rationale for preferential tax treatment of employee stock options is to support younger and growing Canadian businesses. The Government does not believe that employee stock options should be used as a tax-preferred method of compensation for executives of large, mature companies.

It is for this reason that Budget 2019 announced the Government's intention to limit the use of the current employee stock option tax regime, and to move toward aligning it more closely with that of the United States for employees of large, long-established, mature firms.

In 2019, the government appears to agree with the historical policy rationale for the preferred taxation regime for employee stock options. However, because such preferences appear to have been utilized disproportionally by only the "wealthiest Canadians" this is presumably unfair. I have a few observations about this:

- In order to justify the proposed change, the Department of Finance only released 2017 statistics. This is a very narrow snapshot. I'm curious as to what the statistics would look like since 1972. In my opinion, this would give a much more thorough view and better analysis rather than one year;

- While the above 2017 statistics reflect that the benefits disproportionately benefit the "wealthy", I wonder what the statistics would look like if the option holding period was considered. It is my experience that options are generally only exercised when the FMV of the underlying shares rise above the exercise price and often the options are held for a long period of time to get to that point while the employee / executives are working hard to help increase the value of the company they work for. This type of analysis would, again, give a better picture as to whether or not the tax preference disproportionately benefits the "wealthy" and whether such exercises simply result in "lumpy" incomes that distort the statistics inappropriately;

- When making the announcement for the change, the Department of Finance stated that it will be aligning the taxation treatment of stock options more closely with that of the United States regime. I guess the first question is "why"? Has the taxation policy for employee stock options in the United States been very successful and achieved its policy objectives? If so, I'd like to see some empirical analysis and evidence to support that. In addition, given the economic environment that we are in – especially given the competitiveness challenges that Canada is experiencing after US tax reform – this seems to me to be an inopportune time to move the tax treatment of employee stock options closer to that of the United States. In our country's chase for skilled labor, maintaining a tax preference system for employee stock options seems ideal. However, to be fair, if the Department of Finance can "get it right" when developing the characteristics for non-CCPCs to be exempt from the new regime, then perhaps that might help maintain a competitive tax advantage as compared to the United States. (It should also be added that effective personal tax rates are generally lower in the United States than in Canada. For example, the U.S. federal tax bracket for the top marginal tax rate kicks in at USD$612,351 vs. CAD$210,372 in Canada, so perhaps a preferential treatment in Canada may be necessary to help "balance the playing field" for top executive talent).

Overall, I'm not convinced that the government has been thoroughly transparent on its reasoning for the policy change. I'm not saying I necessarily disagree with the proposed change. Rather, I'd like to be better convinced that the historical reasoning for the tax preferred regime is no longer relevant. What has been put forward is lacking significant detail, and reads suspiciously like an election promise. While some – like Professor Sandler – believe that our current taxation preference for employee stock options is overly generous, others believe that the preference is helpful for maintaining a competitive advantage with the United States, attracting skilled labor – especially for smaller businesses, and helping to preserve such businesses working capital. In my opinion, it would be much better to change long-standing taxation policy like this through a comprehensive review of our entire Income Tax Act rather than a piecemeal approach that has been the norm since our last reform of 1972. Recently, however, our government has confirmed that it is not interested in comprehensive tax review / reform notwithstanding the many credible people and bodies that are calling for it. Disappointing.

E. So What is Being Proposed to Change?

During the 2015 federal election , one of the Liberal's key campaign promises was to cap the amount of the stock option deduction available. Shortly after the Liberals' 2015 election victory, the new government did not immediately implement their election promise.

The 2019 federal Budget announcement resurrected the 2015 Liberal campaign promise in limited form. As mentioned, the Budget documents were short on detail, but the NWMM contained some of the details that the tax community was waiting for.

The proposals contain details that will essentially eliminate the tax preferred regime for non-CCPC stock options that are caught in the new regime. The preferred regime for CCPCs stock options is not proposed to change. In addition, the government wishes to carve out certain non-CCPCs from the new regime that it is referring to as start-up, emerging, and scale-up companies. As mentioned earlier, the government is seeking input on what characteristics such companies should have in order to be exempt from the new regime with comments requested by September 16, 2019.

If you are an employee that is subject to the new regime, you will now be subject to a $200,000 annual limit that will apply on employee stock option grants (based on the aggregate FMV of the underlying shares at the time the options are granted) that can receive tax-preferred treatment under the current employee stock option tax rules. Employee stock options above the limit will be subject to the new employee stock option tax rules. If an employee is subject to the new rules – and thus taxable on an amount in excess of the $200,000 limit – the employer will be able to deduct a corresponding amount from its income.

The fact that employers may be able to deduct amounts that are subject to full taxation by employees is a bit surprising, and also brings into question how much tax revenues will be raised by this new measure. For example, considering Ontario, where the highest marginal rate on personal income is approximately 54%, the additional tax revenue raised on the new stock option measures will be half of that amount or 27%. With the highest corporate rate in Ontario being 26.5%, this means that for every dollar of taxable income now subject to the full income inclusion for an Ontario resident individual, the Ontario resident corporation – assuming that the employer corporation is Ontario resident – will be able to deduct 26.5% of that amount thus leaving a minor amount of net tax revenues raised. Ultimately the additional tax burden on the individual executives will be pocketed by their employers in the form of a tax deduction.

The 2019 Report on Federal Tax Expenditures estimates that the total cost to the federal government from the tax preferred treatment of stock options for 2019 will be $685 million, and $710 million for 2020. When compared to the overall numbers and other specific tax expenditures, this amount is a small cost to the federal government. Accordingly, it is highly doubtful that the proposed measures will raise significant tax revenues, or reduce the cost to the government for providing the tax preferred regime, but they will certainly increase the amount of complexity and administrative costs for taxpayers.

The $200,000 Exemption Amount

The new rules will apply to employee stock options granted on or after January 1, 2020. The draft legislation contains detailed proposals to implement these new rules but are best described by way of an example. The Backgrounder contains a number of useful examples to help illustrate the impact of the detailed rules and two of these examples are reproduced below:

Examples of how the $200,000 limit will operate and how the new rules for taxing employee stock options could affect employees who are granted stock options

Example 1

Henry is an executive of a corporation that is subject to the new employee stock option tax rules. In 2020, Henry's employer grants him stock options to acquire 200,000 shares at a price of $50 per share (the fair market value of a share on the date the options are granted), with one-quarter of the options vesting in each of 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024. Since the fair market value of the underlying shares at the time of grant in each vesting year ($50 × 50,000 = $2.5 million) exceeds the $200,000 annual limit, the amount of stock options that can receive preferential tax treatment will be capped. In particular, the stock option benefits associated with 4,000 ($200,000 ÷ $50 = 4,000) of the options in each vesting year can continue to receive preferential personal income tax treatment, while the stock option benefits associated with the remaining 46,000 options in each vesting year will be included in Henry's income and fully taxed at ordinary rates and deductible for corporate income tax purposes.

Henry exercises all of these options in 2024, by which time the price of the shares has increased to $70. This means that $3,680,000 (($70 – $50) × 184,000) of the employee stock option benefit will be included in Henry's income and fully taxed at ordinary rates (with a deduction to the employer), while only $320,000 (($70 – $50) × 16,000) of the benefit can receive preferential personal income tax treatment (with no deduction to the employer).

Example 2

Mckayla is an employee of a corporation that is subject to the new employee stock option tax rules. In 2020, her employer grants her employee stock options to acquire 12,000 shares at a strike price of $50 per share, the fair market value of a share on the date the options are granted. Options to acquire 3,000 shares vest in each of 2021, 2022, 2023 and 2024. Since the fair market value of the underlying shares in each vesting year ($50 × 3,000) does not exceed the $200,000 limit, all of the stock option benefits associated with these options will continue to receive preferential personal income tax treatment (with no deduction to the employer).

Mckayla decides to exercise all of these options in 2024, by which time the price of the shares has increased to $70. Her entire stock option benefit of $240,000 (($70 – $50) × 12,000) will receive preferential personal income tax treatment (with no deduction to the employer).

Accordingly, it will be necessary to keep careful track of each vesting year and ensure that the $200,000 exemption limit is correctly calculated. Memories of the 2000 deferral rules and the many incorrect calculations done are certainly top of mind with these new rules. I guess it really is true that what is old becomes new again.

There are other important technical details in the NWMM but are beyond the scope of this blog.

F. So, Where Does This Leave Us?

Today, the windshield is a little clearer in terms of where the government is heading with its proposed policy change to the taxation of employee stock options. However, significant details as to which non-CCPCs will be exempt from the new regime still remain outstanding. Given that the government is asking for public input to be received by September 16, 2019, and the fact that there is a federal election on October 21, 2019, it is highly doubtful that new legislation will be passed into law before the election. Accordingly, these proposals will be left for the "new" government to push forward or abandon.

In the meantime, I would suggest that employers and employees that may be affected by these new rules in 2020 and forward should take the time to carefully assess any impact that the new rules might have on its executive / employee compensation plans / budgets and adjust course quickly.

Footnotes

1 Hyperlink is only available for Canadian Tax Foundation members.

Daniel Sandler, "The Tax Treatment of Employee Stock Options: Generous to a Fault" (2001) 49:2 Canadian Tax Journal 259-302.

2 Professor Sandler was very critical regarding the introduction of these new rules and was not convinced that the new deferral would have any impact on the "brain drain".

Moodys Gartner Tax Law is only about tax. It is not an add-on service, it is our singular focus. Our Canadian and US lawyers and Chartered Accountants work together to develop effective tax strategies that get results, for individuals and corporate clients with interests in Canada, the US or both. Our strengths lie in Canadian and US cross-border tax advisory services, estateplanning, and tax litigation/dispute resolution. We identify areas of risk and opportunity, and create plans that yield the right balance of protection, optimization and compliance for each of our clients' special circumstances.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.

[View Source]