- in United States

- with Inhouse Counsel

- with readers working within the Healthcare, Metals & Mining and Oil & Gas industries

In the third article of our series on the changes to the Competition Act following our overview bulletin, and our greenwashing bulletin, we discuss the impact of the recent amendments on merger reviews in Canada. By way of summary of the major changes:

- The new rules place a renewed importance on market shares and market concentration in the merger analysis. In many cases, transacting parties will have the burden of demonstrating that their transaction is not anticompetitive.

- The merger notification thresholds include sales into Canada, and therefore capture a broader set of transactions that otherwise would have escaped mandatory review under the old law.

- Remedying a substantially anticompetitive merger requires fixing the merger to the point that it can no longer be said to harm competition at all.

We discuss the implications of these changes in detail and touch on a few other updates to Canada's merger review regime below.

1. Mergers Resulting in a Material Increase in Market Concentration are Presumed to Harm Competition

Until the Bill C-59 amendments, the Competition Bureau and the Competition Tribunal could not find that a merger would result in a substantial prevention or lessening of competition based on solely on evidence of an increase in market share or concentration. Following the Bill C-59 amendments, this approach has been turned on its head as the Tribunal is now expressly permitted to consider market shares when considering whether a transaction is likely to lead to a substantial prevention or lessening of competition.

Moreover, a merger that is likely to increase concentration or market share above a statutorily defined threshold is presumed to be anti-competitive meaning the legal and evidentiary burden shifts to the merging parties to demonstrate that their merger is unlikely to prevent or lessen competition substantially. In defining a significant increase in concentration or market share, the amendments adopt the Herfindahl-Hirschman Index ("HHI"), which is the "sum of the squares of the market shares of the suppliers or customers". However, unlike the United States where HHI serves as a guideline to assist in analyzing transactions, in Canada a sufficient change in HHI will trigger a presumption that a merger is anticompetitive under the law. This rebuttable presumption will be triggered in a transaction where:

(a) the concentration index (HHI) increases or is likely to increase by more than 100; and

(b) either

1) the concentration index (HHI) is or is likely to be more than 1,800; or

2) the market share of the merging parties is or is likely to be more than 30%.

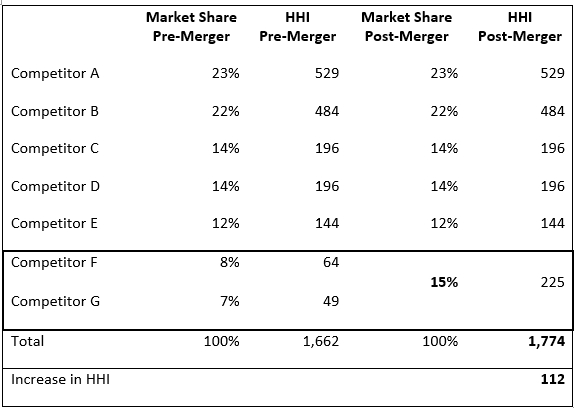

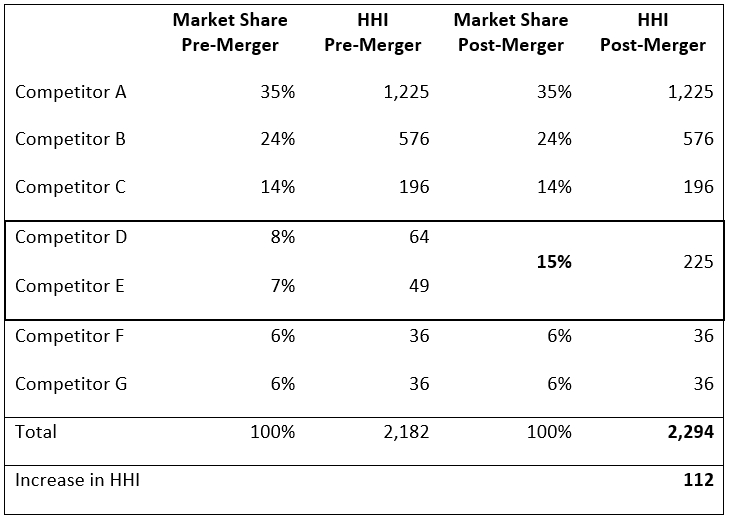

To see how this presumption works in practice, see the illustrative tables in the Appendix to this bulletin showing two proposed mergers in markets with seven competitors. In the first example, the sixth-largest and seventh-largest competitors in a less concentrated market merge to become the third-largest competitor at a 15% share. As shown in the Appendix, while the HHI increases by more than 100 in this example, the presumption is not triggered because the HHI of the market remains below 1,800 and the parties' combined share is less than 30%. In the second example, the fourth-largest and fifth-largest competitors in a more concentrated market merge to become the third-largest competitor at a 15% share. However, unlike the previous example, the Appendix shows that the anticompetitive presumption is met in this example because the HHI increases by more than 100 and the HHI of the market exceeds 1,800.

In real-world scenarios, it is very rare to have agreed-upon market shares, so there will be even more importance on analysis and expert evidence advocacy relating to geographic and product market definitions and how shares should be calculated. Also, as a practical matter, given the size of the Canadian economy, in-market / strategic transactions will have a strong likelihood of triggering this presumption.

If the Bureau or Tribunal determines that the structural presumption is made out, parties to the merger may attempt to rebut the presumption, but they bear the onus of showing based on other factors that it is not likely that a substantial lessening or prevention of competition will occur.

We anticipate that these amendments will result in an increasing number of mergers being challenged by the Bureau.

2. Additional Mergers are Subject to Mandatory Notification

Mergers that meet certain financial thresholds are required to be notified to the Bureau prior to closing, allowing the Bureau to assess whether these mergers are likely to lead to a substantial prevention or lessening of competition before the deals close. The recent amendments expand the scope of the target size threshold to include import sales, which will result in more mergers being caught by this pre-closing notification obligation.

Prior to Bill C-59 passing, this threshold asked whether the target being acquired had either C$93 million in assets in Canada or $93 million in gross revenues from sales generated by those assets (either via domestic sales within Canada or via export sales from Canada). The Bill C-59 amendments expand the revenues branch of the test to also include any sales that the target makes into Canada in addition to domestic sales and exports. This change will capture transactions not previously notifiable, particularly in cases where the target has a modest Canadian "on the ground" presence but has significant sales into Canada from its foreign operations.

For a complete overview of the compete Competition Act's merger notifications thresholds, please see our thresholds chart here.

3. More Expansive Remedies will be Required to Fix Anticompetitive Mergers

Prior to the C-59 amendments, it was sufficient to provide a remedy that would likely result in the merger no longer "substantially" harming competition.

Bill C-59 amendments now advise that remedies to address a merger that substantially harms competition should restore competition to the competitive levels that existed prior to the merger. By contrast, if a merger harms competition, but not substantially, the merger is allowed to proceed unremedied. This change, and the lack of parallelism (since mergers may only be challenged if they are likely to lead to a substantial impact on competition, but if challenged the remedies must eliminate any impact on competition), may provide an incentive for merging parties to find "fix-it-first" type-remedies that address potential substantial competition harm before notifying their transactions to the Bureau.

4. Other Changes to the Merger Regime

In addition to the major changes above, other recent amendments to the Competition Act also:

- Repeal the merger efficiencies defence (as of December 15, 2023) that had allowed merging parties to defend an otherwise anticompetitive merger by establishing that the likely efficiency gains would offset the anticompetitive effects of the merger. Merging parties can still raise efficiencies as a consideration demonstrating that a merger will not be anticompetitive if those efficiencies will result in lower variable costs, lower prices, improved opportunities for collaboration and knowledge sharing or other benefits that can improve the performance of the combined business.

- Increase the time that the Bureau can challenge mergers that were not formally notified from one year to three years after closing.

- Require that the Bureau and Tribunal consider the impact of a merger on labour markets when determining whether a merger is likely to lead to a substantial prevention or lessening of competition. While the Bureau has indicated that it was already considering labour competition in its assessment of whether mergers are anticompetitive, this amendment represents a signal from Parliament that labour considerations may need to be afforded additional prominence in merger reviews.

- Prevent merging parties from completing transactions until the Tribunal decides any interim injunction application filed by the Bureau.

McMillan's Competition & Antitrust Group thanks Natalie Cunningham (Summer Student) for her contributions to this bulletin.

Appendix – Sample Merger Concentration Calculations

A) Presumption of Anticompetitive Merger is not Met

Anticompetitive presumption is not met: HHI increased by 112 (>100), but the market share of the merging parties is only 15% (not greater than 30%) and the total HHI of the market is only 1,774 (not greater than 1,800).

B) Presumption of Anticompetitive Merger is Met

Anticompetitive presumption is met: HHI increased by 112 (>100) and the total HHI of the market is 2,294 (>1,800).

The foregoing provides only an overview and does not constitute legal advice. Readers are cautioned against making any decisions based on this material alone. Rather, specific legal advice should be obtained.

© McMillan LLP 2024