- with readers working within the Consumer Industries industries

- within Litigation, Mediation & Arbitration, Insurance and Law Practice Management topic(s)

- with Senior Company Executives, HR and Finance and Tax Executives

With the scope of trade mark (TM) protection for physical goods and services well accepted and understood, the extent to which trade marks may be able to protect digital assets, such as non-fungible tokens (NFTs)1linked to digital art or physical goods, is largely an open question. In particular, legal questions involving NFTs raise some interesting issues that are yet to be answered particularly regarding the scope of protection and applicability of existing registered trade marks in a virtual environment. This is especially so given the lack of legal jurisprudence and the delays in reform of the regulatory environment needed to clarify such issues in the Metaverse.2

In Australia, the Courts have not yet had the opportunity to consider the question of whether registrations for real world physical goods and services, extend to "virtual" goods and services, or if those goods can be considered identical or similar for the purposes of TM infringement. However, an increasing number of legal cases, albeit in foreign jurisdictions, seems likely to cast further light on the scope of trade mark protection in this digital world and help shape future law in Australia.

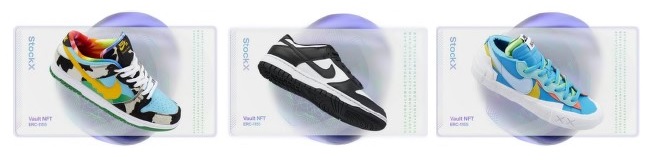

In a dispute between Nike Inc. (Nike) and StockX LLC (StockX) before the US District Court for the Southern District of New York, Nike has asserted trade mark infringement for the unauthorised promotion and sale of NFTs minted by StockX which utilise the Nike trade mark in digital renders of Nike sneakers. StockX is a collectibles marketplace and describes its mission "to provide access to the world's most coveted items in the smartest way possible" including limited edition sneakers, clothing, trading cards and accessories. Nike contends that StockX sells these NFTs to consumers who mistakenly believe the NFTs are authorised by Nike. Below are reproductions of Vault NFTs pictured in Nike's complaint.3

The trade marks in question asserted by Nike include the US "NIKE" word mark #97095855 and US Nike tick #97095944. According to Nike, "Recognising firsthand the immense value of Nike's brands, StockX has chosen to compete in the NFT market not by taking the time to develop its own intellectual property rights, but rather by blatantly freeriding, almost exclusively, on the back of Nike's famous trademarks and associated goodwill". StockX has responded by saying that it was a "mischaracterisation of the service StockX offers through its NFT experience" and that the minted NFTs depict proof of ownership of physical assets that can be readily traded in for the associated physical shoes stored in a StockX facility. In essence, the StockX defence is that NFTs are a "key" to access a stored physical good rather than "virtual products" themselves.

Interestingly, in this dispute, the trade marks in question asserted by Nike have been filed in categories including "[d]ownloadable virtual goods, namely computer programs featuring footwear" and "[r]etail store services featuring virtual goods, namely footwear". Several other well known brands, such as Gucci, Ralph Lauren, Valentino, Marc Jacobs and Alexander McQueen have filed trade marks accordingly. A similar strategy is also increasing being adopted in Australia with several brand owners choosing to file in class 9 (computer and scientific apparatus and software), class 35 (retail, business and advertising services), class 41 (entertainment services) and/or class 42 (scientific and technological services) for categories such as "digital materials" and "downloadable virtual goods" as future protection for virtual goods and services in the Metaverse. This is despite the fact that the classification system in Australia has not yet comprehensively adapted to the evolving consumer experience in the Metaverse and Web3.

A further interesting case concerns the dispute between the luxury design house Hermès of Paris, Inc. (Hermès) and Mason Rothschild also before the US District Court for the Southern District of New York for trade mark infringement of the famous BIRKIN trade mark (and other causes of action). The dispute stems from Mr Rothschild's minting of 100 NFTs linking to a depiction of a digital Hermès BIRKIN bag covered in faux fur and patterns, polka dots, and artworks such as the Mona Lisa and Van Gogh's Starry Night. Below are reproductions of Mr Rothschild's "MetaBirkin" hand bags pictured in Hermès complaint.4

Hermès asserts that that Mr Rothschild's use of "MetaBirkin" infringes the BIRKIN trade mark by adding the generic prefix "meta" to denote "fake Hermès products in the metaverse" with several consumers mistakenly believing that Hermès was affiliated with the MetaBirkin NFTs. Mr Rothchild's defence focusses on his claim that the First Amendment of the US Constitution gives him "the right to make and sell art that depicts Birkin bags, just as it gave Andy Warhol the right to make and sell art depicting Campbell's soup cans" and also that he and his the "MetaBirkin" NFTs included the following disclaimer at the bottom of his website: "We are not affiliated, associated, authorized, endorsed by, or in any way officially connected with the HERMÈS [sic], or any of its subsidiaries or its affiliates", to avoid any likelihood of confusion as to his relationship with Hermès.

In an interlocutory dismissal motion (which was denied on 5 May 2022), the Court analysed Hermès trademark infringement arguments advanced and held that the "MetaBirkin" NFTs qualified as artistic works, and thus were subject to the Second Circuit's Rogers v. Grimaldi test for balancing free speech against trade mark rights. In a case of first impression, the Court held that the "MetaBirkin" images were artistic works even though they were linked to NFTs:

"[B]ecause NFTs are simply code pointing to where a digital image is located and authenticating the image, using NFTs to authenticate an image and allow for traceable subsequent resale and transfer does not make the image a commodity without First Amendment protection any more than selling numbered copies of physical paintings would make the paintings commodities for purposes of Rogers."

Although the case will largely turn on US law and First Amendment protection under the US Constitution, it is expected that the case will assist in navigating whether real-world trade marks are actually enforceable in a virtual context and in light of emerging technologies. It is also worth noting that Hermès had not filed specifically in classes typically used in relation to the Metaverse and Web3, and the case will examine how far protections may extend to other classes despite not being claimed.

The Hermès' and Nike cases are likely to have a considerable impact on the market for NFTs one way or another and it will be interesting to see how US courts grapple with some of the novel legal issues NFTs present. Such jurisprudence may assist in the likely interpretation before the Courts in Australia when infringements under section 120(2) of the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) for closely related goods and services and section 120(3) for usage of unrelated goods and services will be determined. Hopefully, in the near future, the Australian Courts will have a similar opportunity to tackle the interaction between NFTs and Australian intellectual property rights.

New regulation is on its way

Given the proliferation of NFTs across several use cases, it would seem that the appetite for increased regulation (and taxation) of cryptocurrencies and tokens will keep regulators occupied in 2023. There is clearly momentum for legislative change afoot and this may well extend to reform of the Australian classification system for trade marks in response to the evolving consumer experience in the Metaverse and Web3. Brand owners and other interested parties would be well placed to keep alert to the changing landscape as these reforms unfold.

Footnotes

1 For a detailed discussion of NFTs please refer to my earlier article "The NFT - perils and pitfalls in the commercialisation of copyright works" at https://www.bennettphilp.com.au/blog/nfts-perils-and-pitfalls-in-the-commercialisation-of-copyright-works

2 The term "Metaverse" is commonly understood in colloquial usage to represent a network of virtual worlds focussed on social connection often linked to advancing virtual reality technology due to the increasing demands for immersion as influenced by Web3.

3 https://business.cch.com/ipld/NikeStockXComplaint20220203.pdf

4 https://www.documentcloud.org/documents/21181175-hermes-international-vs-mason-rothschild

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.