- within Environment, Litigation and Mediation & Arbitration topic(s)

US Market Review And Outlook

Review

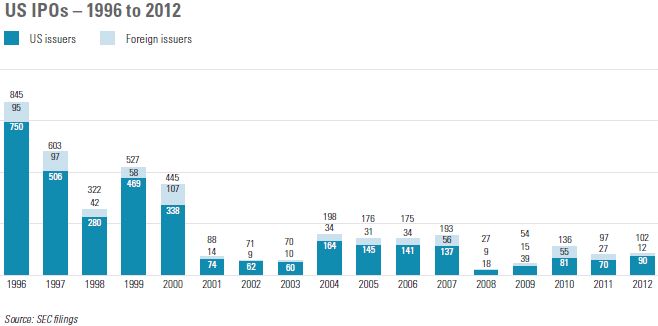

The US IPO market produced 102 IPOs in 2012—a 5% increase from the 97 IPOs in 2011. Before drying up in mid- May, IPO activity was at its highest level for the comparable period in any year since 2007. Although deal flow picked up in the fall, the fourth quarter tally in 2012 was the lowest since 2002.

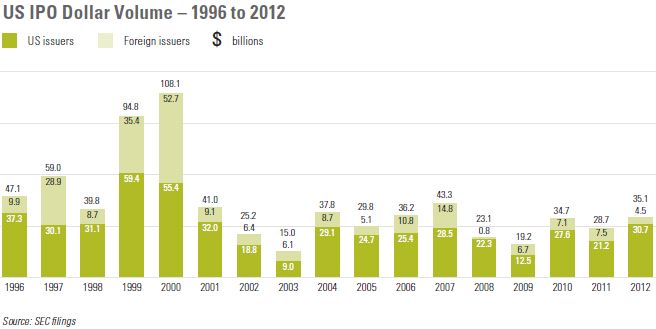

Gross proceeds increased 22%, from $28.7 billion in 2011 to $35.1 billion in 2012, primarily due to Facebook's $16.0 billion offering—the third-largest IPO in US history. The two other billiondollar IPOs of 2012 came from Mexican financial services company Santander ($2.9 billion) and real estate services company Realogy ($1.08 billion).

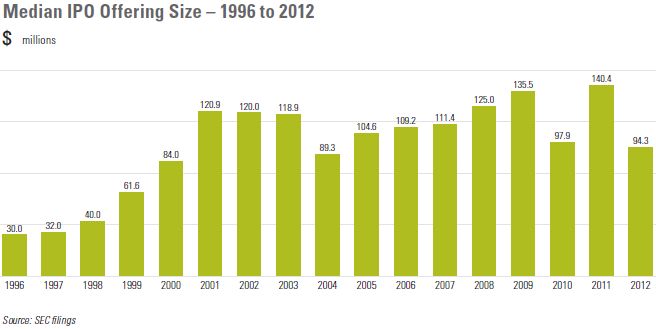

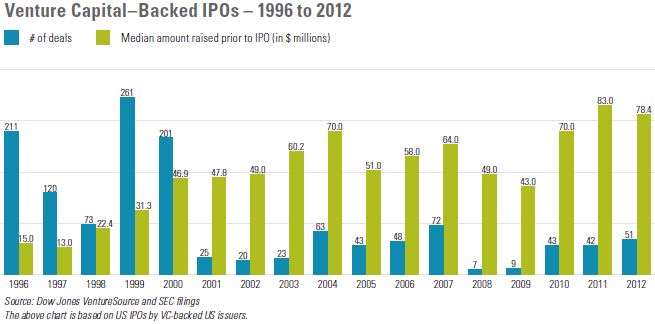

Median IPO size declined 33%, from $140.4 million in 2011 to $94.3 million in 2012, reflecting an increase in the number of VC-backed IPOs—which tend to be smaller—from 42 to 51.

The average first-day gain for all IPOs in 2012 was 16%, compared to 14% in 2011, and was the highest such figure since 2000. In 2012, 20% of the year's offerings were "broken" IPOs (IPOs whose stock closes below the offering price on their opening day), compared to 26% in 2011. The percentage of broken IPOs in 2012 was the lowest since 2003, when the IPO market was open to only the most select companies.

There was only one "moonshot" (an IPO that doubles in price on its opening day) in 2012. Enterprise software company Splunk saw its stock price jump 109% in first-day trading. Other impressive first-day gains were produced by Millennial Media (up 92%), Annie's (up 89%) and Proto Labs (up 81%).

Aftermarket performance rebounded in 2012, following a weaker showing in 2011. The average 2012 IPO gained 22% from its offering price by the end of the year, with 64% of the year's IPOs trading at or above their offering price at year-end. In contrast, the average 2011 IPO lost 13% from its offering price by the end of 2011, with only 39% of the year's IPOs trading at or above their offering price at year-end 2011.

The best-performing IPO of 2012 was Chinese social platform YY, which ended the year 174% above its offering price, followed by Proto Labs (up 146%) and HomeStreet (up 132%). The average IPO gained 14% from first-day close to year-end in 2012, compared to an 18% decline for the IPO class of 2011 from first-day close to year-end in 2011.

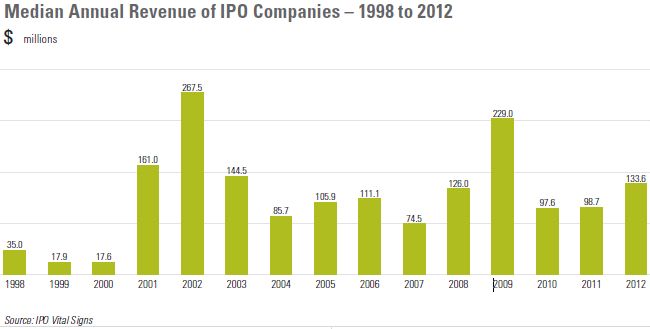

The percentage of profitable IPO companies increased from 51% in 2011 to 55% in 2012. Despite the increase, this was still a lower percentage than in any other year since 2001. The median annual revenue of IPO companies increased 35%, from $98.7 million in 2011 to $133.6 million in 2012. These results reflect the traits of a bifurcated IPO market, with larger and more profitable companies (often private equity–backed) on one end of the spectrum and smaller technology and life sciences companies (often venture capital–backed) on the other.

Individual components of the IPO market fared as follows in 2012:

- VC-Backed IPOs: With 51 offerings, US issuer venture capital–backed IPOs represented 50% of all IPOs in 2012, compared to 42 deals and a 43% market share in 2011. Most of these IPOs were by technology or life sciences companies. Among US issuers, the median offering size of VC-backed IPOs in 2012 was $81.0 million, compared to $170.5 million for non–VC-backed IPOs. The average 2012 US issuer VC-backed IPO gained 25% from its offering price through year-end, in contrast to the average loss of 6% during 2011 for the prior year's class.

- PE-Backed IPOs: Private equity– backed companies grabbed 27% of the market in 2012, with 28 IPOs, up from 17 offerings and an 18% market share in 2011. Realogy's $1.08 billion IPO was the eighth-largest private equity–backed IPO in US history.

- Tech IPOs: Deal flow for technology and life sciences companies remained strong in 2012. Tech-related companies produced 58% of the year's IPOs, down slightly from 61% in 2011. Tech IPOs fared marginally better in the aftermarket than IPOs in other sectors, with an average gain through yearend of 22%, compared to the average gain of 21% for non-tech IPOs.

- Foreign IPOs: Foreign issuers accounted for 13% of the market in 2012, down from 28% in 2011 and 40% in 2010. These results represent the lowest number of foreign-issuer IPOs in the US since 2008, and the lowest share of the US IPO market since 2002. China, which produced a lofty 40 US IPOs in 2010, and another 13 in 2011, sent only a pair of IPOs to the US in 2012, amid concerns about the reliability of financial information provided by Chinese issuers.

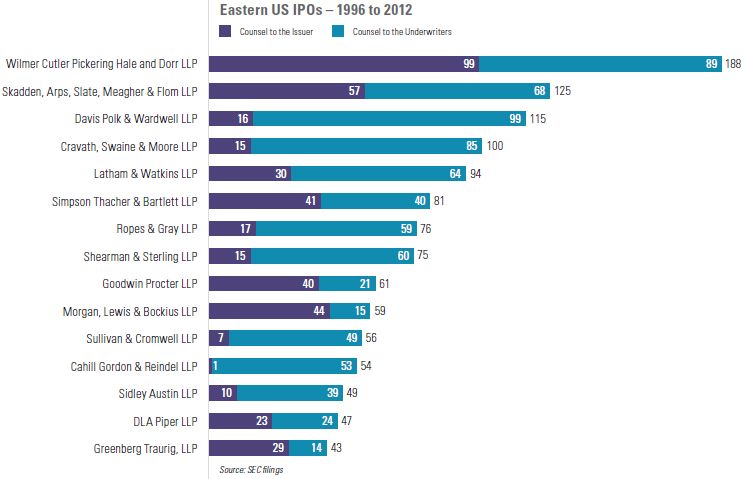

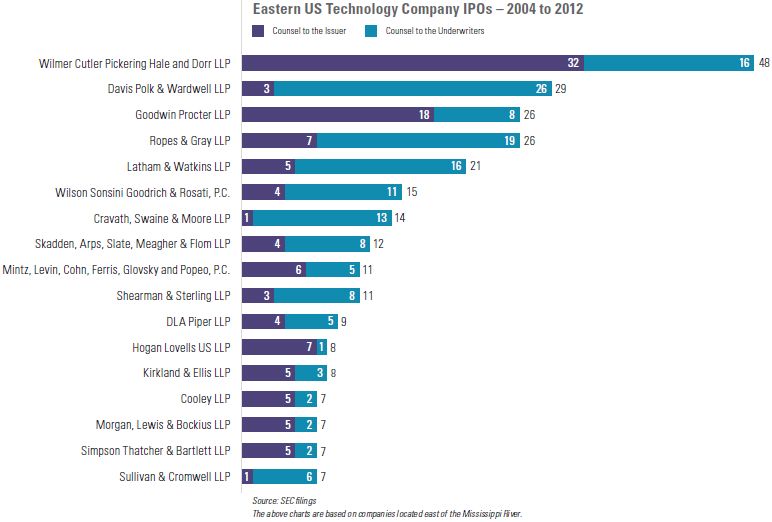

In 2012, companies based in the western United States (west of the Mississippi River) completed 53 IPOs, led by California with 32 IPOs and Texas with 12—largely a mix of energy-related and consumer goods companies. Eastern US–based issuers accounted for 36 IPOs, and foreign issuers accounted for the remaining 13 IPOs.

Outlook

IPO market activity in the coming year will depend on a number of factors, including the following:

- Economic Growth: Although the US economy has been improving by some measures for more than three years, recovery has been accompanied by mixed signals. Much of the developed world is still recovering from a prolonged and deep recession, and economic conditions may be worsening in parts of Europe. Sustained economic growth will be key to an increase in IPO activity from the level of approximately 100 IPOs annually in the past two years.

- Capital Market Stability: Stable and robust capital markets remain a precursor to IPO activity. Dips in May and October aside, the capital markets continued their upward trend in 2012, with the Dow gaining 7% and the Nasdaq increasing 16%. Since the end of 2009, the Dow and Nasdaq have posted gains of 26% and 33%, respectively, and yet there has been no meaningful uptick in IPO activity. Reduced market volatility might help avoid a continuation of the stop-and-go IPO market of recent years.

- Impact of JOBS Act: Enacted with great fanfare in April 2012, the JOBS Act is intended to improve access to the public capital markets for startup companies.

The JOBS Act provides an "emerging growth company" (EGC) up to the last day of the fiscal year following the fifth anniversary of its IPO to come into full compliance with certain disclosure and accounting requirements. In general, an EGC is any company that had annual revenues of less than $1 billion (indexed for inflation) during its most recently completed fiscal year—a standard that the vast majority of all IPO companies can satisfy. To date, there does not appear to be any evidence that the JOBS Act is producing a significant increase in the number of companies pursuing IPOs, perhaps because of the modest nature of relief under the JOBS Act in relation to the remaining regulatory burden of being a public company and the ready availability of private funding as an alternative to an IPO. The extent to which the JOBS Act prompts EGCs that otherwise would have stayed private to go public remains to be seen.

- Venture Capital Pipeline: Venture capitalists depend on IPOs—along with company sales—to provide liquidity to their investors. There has been a resurgence in VC-backed IPOs over the last three years, and a number of VC-backed technology and social media–related companies are waiting in the wings to pursue highly anticipated IPOs in 2013. The JOBS Act significantly increased the maximum number of stockholders that a private company may have without registering as a public company, which may result in some companies deferring IPOs longer than in the past. The pool of VC-backed IPO candidates is also affected by trends in venture capital investing, including the timeline from initial funding to IPO. According to Dow Jones VentureSource, the median time from initial equity financing to IPO increased to 7.4 years in 2012 from 6.4 years in 2011.

- Private Equity Impact: Private equity investors also seek to divest portfolio companies or achieve liquidity through IPOs. PE-backed companies are usually larger and more seasoned than VC-backed companies or other startups pursuing IPOs, and thus can be strong candidates in a demanding IPO market. With private equity investors still holding a variety of notable companies from the precrisis buyout boom and sitting on near record levels of "dry powder" (unspent capital that investors have committed to provide), private equity–backed IPOs can be expected to continue to enter the IPO market as conditions permit.

The IPO market has produced mixed results so far in 2013, but recent trends present reason for optimism. After generating the largest number of January IPOs since 2006 and the highest amount of January IPO proceeds since 2000, the market slowed to just four IPOs in February before rebounding with eight offerings in March. While gross proceeds—buoyed by a handful of large offerings—were up slightly in the first quarter of 2013 compared to the first quarter of 2012, the 2013 tally of 20 IPOs trailed 2012's figure by a wide margin. The strong finish to the quarter, as well as the recent uptick in filings and low level of withdrawals in recent months, however, bode well for future IPO activity. Year-to-date highlights include the $2.2 billion IPO of Pfizer's animal health unit Zoetis, several prominent tech IPOs, and a total of five IPOs in the life sciences sector.

Profile of Successful IPO Candidates

What does it really take to go public? There is no single profile of a successful IPO company, but in general the most attractive candidates have the following attributes:

- Outstanding Management: An investment truism is that investors invest in people, and this is even more true for companies going public. Every company going public needs experienced and talented management with high integrity, a vision for the future, lots of energy to withstand the rigors of the IPO process, and a proven ability to execute.

- Market Differentiation: IPO candidates need a superior technology, product or service in a large and growing market. Ideally, they are viewed as market leaders. Appropriate intellectual property protection is expected of technology companies, and in some sectors patents are de rigueur.

- Substantial Revenues: With some exceptions, substantial revenues are expected—at least $50 million to $75 million annually—in order to provide a platform for attractive levels of profitability and market capitalization.

- Revenue Growth: Consistent and strong revenue growth—25% or more annually— is usually needed, unless the company has other compelling features. The company should be able to anticipate continued and predictable expansion to avoid the market punishment that accompanies revenue and earnings surprises.

- Profitability: Strong IPO candidates generally have track records of earnings and a demonstrated ability to enhance margins over time.

- Market Capitalization: The company's potential market capitalization should be at least $200 million to $250 million, in order to facilitate development of a liquid trading market. If a large portion of the company will be owned by insiders following the IPO, a larger market cap may be needed to provide ample float.

Other factors can vary based on a company's industry and size. For example, many biotech companies will have much smaller revenues and not be profitable. More mature companies are likely to have greater revenues and market caps, but slower growth rates. High growth companies are likely to be smaller, and usually have a shorter history of profitability. Beyond these objective measures, IPO candidates need to be ready for public ownership in a range of other areas, including accounting preparation; corporate governance; financial and disclosure controls and procedures; employee recruitment and retention; external communications; and a variety of corporate housekeeping tasks.

How Do You Compare? Some Facts About the IPO Market

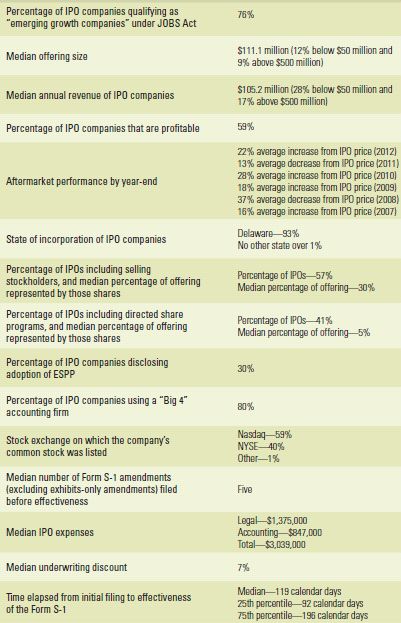

The metrics below are based on combined data for all US IPOs from 2007 through 2012.

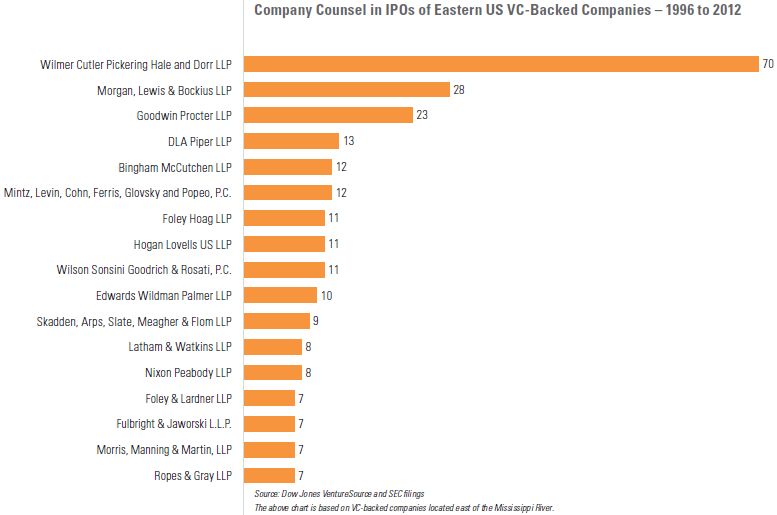

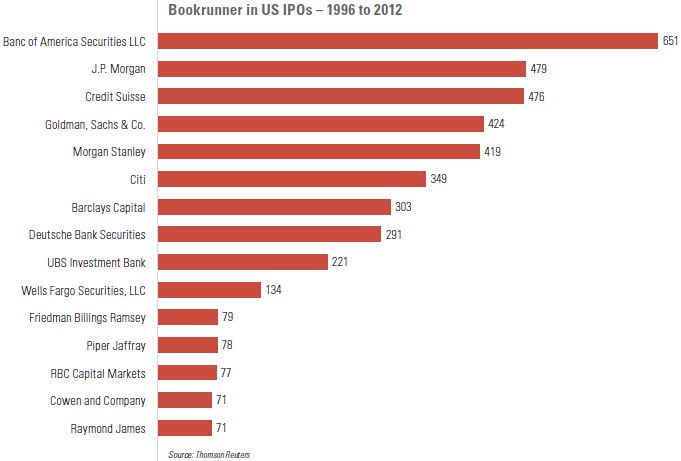

Law Firm and Underwriter Rankings

Regional Market Review and Outlook

California

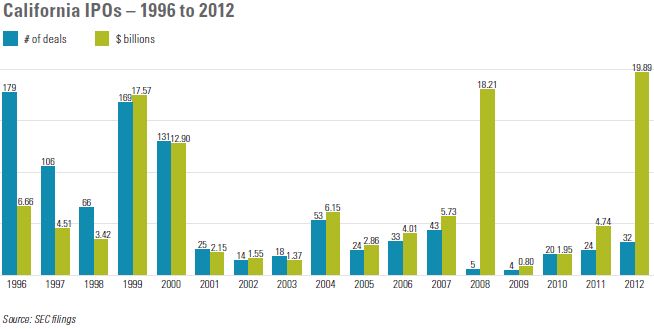

The number of California IPOs increased 33%, from 24 in 2011 to 32 in 2012, outpacing the 5% increase in the overall US IPO market. California's deal tally in 2012 was its highest since 2007 and slightly exceeded its annual average of 30 IPOs that prevailed between 2001 and 2007.

Buoyed by Facebook's $16.0 billion IPO, gross proceeds quintupled from $4.74 billion in 2011 to $19.89 billion in 2012. Other large California IPOs in 2012 came from Workday ($637 million) and Oaktree Capital ($380 million).

The median offering size of California IPOs declined 19%, from $112.5 million in 2011 to $91.5 million in 2012.

The California IPO market continued to be dominated by technology-related companies in 2012. Tech companies accounted for 84% of the state's offerings, compared to 58% of the overall US market. We expect this trend to continue in 2013.

The state's average IPO ended 2012 up 23% from its offering price, with 22 IPOs (69%) trading above their offering price at year-end. California's best-performing IPOs of 2012 were Guidewire Software (up 129% from its offering price at year-end), WageWorks (up 98%) and Workday (up 95%).

With the largest pool of venture capital–backed companies in the country, California should produce significant IPO activity in 2013, including offerings from social media, biotechnology and cleantech companies. California had six IPOs in the first quarter of 2013: KaloBios Pharmaceuticals ($70 million), Marin Software ($105 million), Model N ($104.5 million), Silver Spring Networks ($80.8 million), TRI Pointe Homes ($233 million) and Xoom ($101 million).

Mid-Atlantic

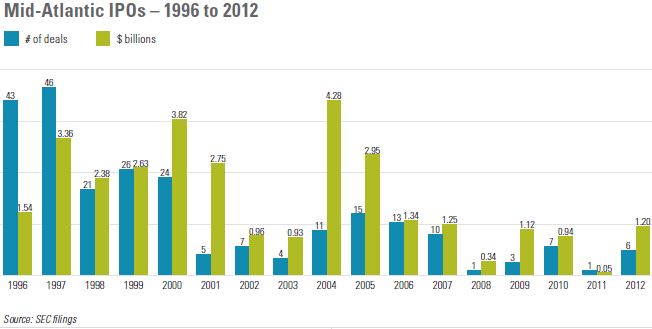

The mid-Atlantic region of Virginia, Maryland, North Carolina, Delaware and the District of Columbia produced six IPOs in 2012, compared to one solitary IPO in 2011.

With the substantial increase in deal flow, gross proceeds in the mid-Atlantic region soared from $54.0 million in 2011 to $1.2 billion in 2012. The region's largest IPO of 2012 was by The Carlyle Group ($671 million).

Maryland led the region with three IPOs in 2012. Virginia, North Carolina and the District of Columbia each contributed one IPO.

The average mid-Atlantic IPO in 2012 ended the year 28% above its offering price, with only two IPOs below their offering price at year-end. The region's best-performing IPO was software company Eloqua, which ended the year trading 105% above its offering price.

Technology and defense-related companies historically have accounted for a significant portion of the mid-Atlantic's IPO deal flow (two-thirds of the region's 2012 IPOs were by technology and life sciences companies). We expect this trend to continue in 2013, boosted by life sciences IPOs from the Research Triangle area. In vitro diagnostic company LipoScience completed the region's only IPO ($45 million) in the first quarter of 2013.

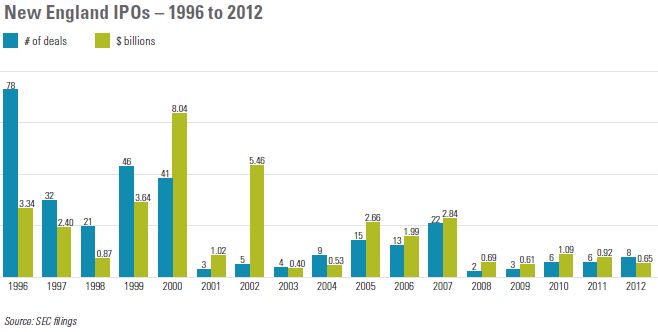

New England

New England produced eight IPOs in 2012, up 33% from the six IPOs in both 2010 and 2011. Gross proceeds fell 29%, from $917 million in 2011 to $648 million in 2012, reflecting a higher number of smaller offerings by technology-related companies.

The median offering size of New England IPOs declined 24%, from $111.4 million in 2011 to $84.5 million in 2012. The largest New England IPOs of 2012 were by M/A-COM Technology Solutions Holdings ($114.0 million), Merrimack Pharmaceuticals ($101.1 million) and KAYAK Software ($91.0 million).

Tech-related companies have historically dominated the New England IPO market and 2012 was no exception. All eight of the region's IPOs in 2012 were by technology or life sciences companies.

Massachusetts accounted for seven of the region's IPOs—the third-highest total from any state, after California (with 32 IPOs) and Texas (with 12 IPOs). New England's remaining IPO came from Connecticut.

Software company Demandware was the region's best-performing IPO of 2012, ending the year 71% above its offering price. With only three IPOs trading above their offering price at year-end, however, the average New England IPO gained only 10% from its offering price.

With strong levels of venture capital investment and world-renowned universities and research institutions, New England should continue to generate a vibrant crop of IPO candidates. In the first quarter of 2013, New England produced three IPOs: Bright Horizons Family Solutions ($222 million), Enanta Pharmaceuticals ($56 million) and Tetraphase Pharmaceuticals ($75 million).

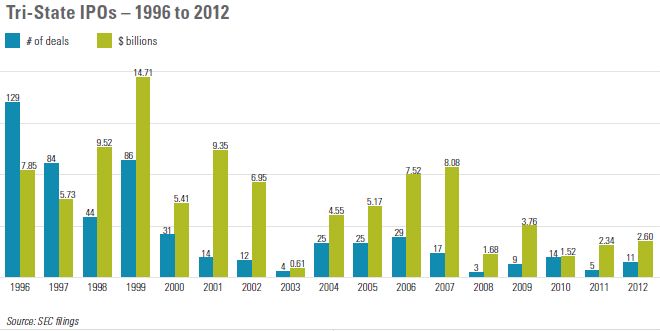

Tri-State

The number of IPOs in the tri-state region of New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania more than doubled, growing from five in 2011 to eleven in 2012.

Buoyed by the $1.08 billion IPO of Realogy Holdings—the third-largest US IPO of the year—gross proceeds in the tri-state region increased from $2.34 billion in 2011 to $2.60 billion in 2012. The next two largest tri-state IPOs in 2012 were by PBF Energy ($533.0 million) and Tumi Holdings ($338.0 million).

New York and New Jersey each produced four IPOs in 2012, with Pennsylvania contributing the remaining three.

The region's average IPO ended the year 39% above its offering price. Overall, eight tri-state IPOs (73% of the year's total) were trading above their offering price at year-end. The tri-state region's best performing IPOs came from Intercept

Pharmaceuticals (up 121%) and specialty value retailer Five Below (up 88%). Venture capital activity in the tri-state region now trails only that of California. With improving market conditions, we expect to see a steady flow of IPOs by venture-backed companies—including those from the social media, software and life sciences sectors—as well as offerings by more seasoned companies. In the first quarter of 2013, the region produced three IPOs, highlighted by the $2.24 billion IPO of Pfizer's animal health unit Zoetis.

Ask Meredith: A Q&A with Former SEC Corp Fin Director Cross

WilmerHale Partner Meredith Cross served as Director of the SEC's Division of Corporation Finance from June 2009 through December 2012. During her tenure at the SEC, she implemented many enhancements to the Division's review process, and oversaw the staff's review of some of the most high-profile IPOs in history. Below is Meredith's perspective on some of the most common questions we hear from IPO companies.

Every IPO undergoes SEC staff review. What can a company do to make that process go as smoothly as possible?

The process will go much more smoothly if you put in the work to make the first submission of your registration statement to the SEC as complete as possible. This includes looking at recent SEC staff comments to similarly situated companies, and addressing any issues that also apply to you. It is not likely that the staff will miss the issue in your filing, so addressing it up front can save you time. In some cases—in the event of an unusual accounting or financial statement presentation issue, for example—you may want to arrange for a pre-filing conference with the staff. Once you receive comments from the staff, answer every question in the letter and answer completely to avoid having several rounds of back-and-forth with the staff. If you do not understand the staff 's comment, call the examiner for clarification before you respond.

Are there other times during the process when the company should pick up the phone and call the examiner?

Absolutely. In particular, it is a good idea to call your examiner if you have special timing needs. Although the staff has regular timing goals for their reviews, they are happy to try to work with you if you have legitimate timing issues. Also, sometimes during the comment process it may become apparent that you and your examiner are not understanding each other—in that case, a call can really help to get everyone on the same page.

What if you do that, but you still find yourself at an impasse with your examiner?

In that case, I would recommend that you call the examiner and ask to speak with the reviewer on the filing. If you are unable to resolve the issue with the reviewer, you may want to ask to speak to the supervisor. This is not something that you should be afraid to do or that you will be penalized for doing. If, for some reason, the examiner does not facilitate the conversation for you, then you should feel free to contact the supervisor directly. The Division of Corporation Finance has posted a useful document on the SEC website outlining the filing review process, which includes a listing of the supervisors in each review office.

What do you see as the most significant impact of the JOBS Act on IPOs so far? Do you expect other significant changes in the future as a result of the JOBS Act?

The JOBS Act provision that provides for confidential submission of draft registration statements by emerging growth companies has been widely embraced by eligible companies and, although it is impossible to know for sure, that provision appears to have resulted in an increase in the number of IPO filings. Companies also are taking advantage of some of the reduced disclosure permitted under the JOBS Act. So far, I am not aware of significant use of the provisions relating to pre-deal research or testing-the-waters, but if the market begins to truly make use of those provisions, these would be significant changes in the way people communicate around IPOs.

Speaking of communications, IPO companies hear a lot about the concept of a quiet period. Does it really inhibit a company's ability to continue to communicate with its customers and employees?

The SEC staff is sensitive to the idea that companies need to be able to communicate with customers and employees during the offering process, and understands that, to some extent, it is hard to contain that information. There have been some recent, high-profile examples of IPO companies' communications with their employees being leaked and raising some issues for the companies in the IPO process. While the staff is not looking for "foot faults," this is an area that does require some caution.

It is generally fine for an IPO company to keep communicating with its customers and employees using whatever well-established practices of communication it already has in place. Of course, you have to be careful about the content of the communications—it is not okay to talk about the IPO with customers, and any discussion of the IPO with employees needs to be carefully thought through—so it is important to make sure that the people handling communications understand the ground rules.

The timing of when the IPO window is open is almost impossible to predict. What happens if a company ends up needing to seek additional financing during the IPO process?

Companies have a fair bit of flexibility to seek financing during the IPO process. Capital raising outside the IPO is accommodated under the SEC's guidance on this topic, generally so long as you structure it carefully and you do not locate your investors through the process of filing your IPO registration statement.

It's crystal ball time. Imagine we are discussing the IPO process 10 years from now. What do you think will be some of the major differences from today?

It is very hard to predict, but we may see some big changes if market participants begin to proactively use the JOBS Act provisions that really open up pre-deal communications in the form of testing-the-waters and research. Another thing that will be interesting is to see how the IPO market evolves over time. There are several JOBS Act provisions that appear to make it easier for companies to stay private—provisions that raise the thresholds for SEC reporting and ease certain restrictions on, and create new avenues for, capital raising in unregistered transactions. As a result, we may see fewer companies choosing to do IPOs, unless they can see very real benefits from being publicly traded.

SEC "Likes" Social Media—If Done Correctly

Following its IPO, a newly public company will have investor relations responsibilities that are subject to a variety of rules that regulate how and when a public company may communicate with investors. For example, Regulation FD prohibits a public company from disclosing material non-public information to securities market professionals and other specified persons unless the company also discloses the information publicly.

At the same time, the world of investor relations is rapidly changing as a result of the explosion of social media as both a cultural phenomenon and a means of communication. The SEC's principal guidance on electronic communications, issued in 2008, does not even use the phrase "social media," yet by mid-2011 President Obama was holding a "Twitter town hall meeting" and nearly all investor relations professionals now consider social media to be an essential element of effective corporate communications.

In a report issued on April 2, 2013, the SEC confirmed something that its staff had been saying for years: public companies can use social media outlets such as Facebook and Twitter to disseminate material information in a manner that satisfies Regulation FD, but only if that usage complies with the principles outlined by the SEC in its 2008 guidance on the use of company websites.

In its 2008 guidance, the SEC indicated that website posting may, in some circumstances, be adequate public disclosure under Regulation FD. The 2008 guidance, which the SEC's report confirms is equally applicable to social media communications, states that when evaluating whether a communication is sufficient under Regulation FD company must consider whether:

- the communication is made via a recognized channel of distribution;

- the means of communication disseminates the information in a manner that makes it available to the securities marketplace in general; and

- there has been a reasonable waiting period for investors and the market to react to the information.

The required analysis under Regulation FD must be made on a case-by-case basis. As noted in the report: "The central focus of this inquiry is whether the company has made investors, the market, and the media aware of the channels of distribution it expects to use, so these parties know where to look for disclosures of material information about the company or what they need to do to be in a position to receive this information."

The SEC's report expressly rejected the idea that having a large number of followers, in and of itself, makes a forum FD-compliant. The report also highlighted some factors that may be especially relevant in the social media context, including providing appropriate notice to investors about:

- the specific social media channels the company will use for the dissemination of information, so that investors are in a position to subscribe, join, register for or otherwise review those particular channels; and

- the types of information that may be disclosed through these channels.

The report was issued by the SEC in conclusion of its enforcement staff 's investigation into whether Netflix's CEO had violated Regulation FD by reporting on his personal Facebook page that Netflix's monthly online viewing had exceeded one billion hours for the first time; neither he nor Netflix simultaneously publicly disclosed this information through any other means. The report notes that neither Netflix nor its CEO had previously used the CEO's personal Facebook page to announce company metrics, and that Netflix had not previously informed investors that the CEO's personal page would be used to disclose information about Netflix. Instead, the report notes that Netflix had consistently directed the public to Netflix's corporate website, Facebook page, Twitter feed and blog for information about Netflix. Stating that it recognized that there has been market uncertainty about the application of Regulation FD to social media, the SEC determined not to initiate an enforcement action or allege wrongdoing by Netflix or its CEO.

While the report reflects the SEC's recognition of the increased use and importance of social media, as well as the SEC's willingness to allow companies to explore new ways to communicate with investors, it does not fundamentally change the regulatory framework for analyzing Regulation FD compliance. At least for now, as was the case before the report, most public companies (especially newly public ones) will continue to be best served by disseminating material information through a press release or a Form 8-K, supplemented by website posting, social media and other means of dissemination. However, with appropriate groundwork by companies—based on the principles outlined in the SEC's 2008 guidance—the report may well contribute to increased acceptance of social media as an investor communication tool.

Companies should remain vigilant about dissemination of information through executives' personal social media accounts, as the report warns that: "[D]isclosure of material, non-public information on the personal social media site of an individual corporate officer, without advance notice to investors that the site may be used for this purpose, is unlikely to qualify as a method 'reasonably designed to provide broad, non exclusionary distribution of the information to the public' within the meaning of Regulation FD. This is true even if the individual in question has a large number of subscribers, friends, or other social media contacts, such that the information is likely to reach a broader audience over time. Personal social media sites of individuals employed by a public company would not ordinarily be assumed to be channels through which the company would disclose material corporate information."

Which Items of JOBS Act Relief are EGCs Adopting?

The cornerstone of the JOBS Act is the creation of an "IPO onramp," which provides "emerging growth companies" (EGCs) a phase-in period of up to approximately five years to come into full compliance with certain disclosure and accounting requirements. Although the overwhelming majority of all IPO candidates are likely to qualify as EGCs approximately 90% of all IPO companies in the five years preceding the enactment of the JOBS Act in April 2012 would have qualified— the extent to which EGC standards are being adopted in IPOs varies widely.

Confidential Submission of Form S-1

An EGC is able to submit a draft Form S-1 registration statement to the SEC for confidential review instead of filing it publicly on the SEC's EDGAR system. A Form S-1 that is confidentially submitted must be substantially complete, including all required financial statements and signed audit reports. The SEC review process for a confidential submission is the same as for a public filing. A confidentially submitted Form S-1 must be filed publicly no later than 21 days before the road show commences.

Confidential submission enables an EGC to maintain its IPO plans in secrecy and delay disclosure of sensitive information to competitors and employees until much later in the process. Depending on the timing, confidential review also means that the EGC can withdraw the Form S-1 without any public disclosure at all if, for example, the SEC raises serious disclosure issues that the EGC does not want made public or market conditions make it apparent that an offering cannot proceed. Confidential submission will, however, delay any perceived benefits of public filing, such as the attraction of potential acquirers in a "dual-track" IPO process.

Reduced Financial Disclosure

In the Form S-1, EGCs are required to provide only two years of audited financial statements (instead of three years), plus unaudited interim financial statements, and need not present selected financial data for any period prior to the earliest audited period (instead of five years). Similarly, an EGC is only required to include MD&A for the fiscal periods presented in the required financial statements. Many investors prefer to continue to receive three full years of audited financial statements and five years of selected financial data, and an EGC may be disadvantaged if it provides less financial information than its non-EGC peers. These deviations from historical norms are more likely to be acceptable to investors in the case of EGCs for which older financial information is largely irrelevant, such as startups in the life sciences industry.

Accounting and Auditing Relief

EGCs may choose not to be subject to any accounting standards that are adopted or revised on or after April 5, 2012, until these standards are required to be applied to non-public companies. This election must be made on an "all or nothing" basis, and a decision not to adopt the extended transition is irrevocable. Although appealing, this decision could make it harder for a company to transition out of EGC status, both from a technical accounting perspective and due to the potential need to reset market expectations. Moreover, the benefits are difficult to assess, as it is hard to predict which accounting standards will be affected in the future, and an EGC's election to take advantage of the extended transition period could make it more difficult for investors to compare its financial statements to those of its non-EGC peers.

In addition, EGCs are automatically exempt from any future mandatory audit firm rotation requirement and any rules requiring that auditors supplement their audit reports with additional information about the audit or financial statements of the company (a so-called auditor discussion and analysis) that the PCAOB might adopt. Any other new auditing standards will not apply to audits of EGCs unless the SEC determines that application of the new rules to audits of EGCs is necessary or appropriate in the public interest.

Reduced Executive Compensation Disclosure

An EGC need not provide Compensation Discussion and Analysis (CD&A); compensation information is required only for three named executive officers (including the CEO); only three of the seven compensation tables otherwise required must be provided; and the Summary Compensation Table is only required to cover two years (as opposed to three years). Investors generally appear willing to accept reduced compensation disclosures in IPOs, although some EGCs voluntarily include some narrative disclosure in lieu of the full CD&A.

Section 404(b) Exemption

EGCs are exempt from the requirement under Section 404(b) of the Sarbanes-Oxley Act that an independent registered public accounting firm audit and report on the effectiveness of a company's internal control over financial reporting (ICFR), beginning with the company's second Form 10-K. It seems likely that many EGCs will adopt this exemption, although the election need not be disclosed in advance in the Form S-1.

EGC Elections in 2012

- Based on IPOs initiated after enactment of the JOBS Act and completed by EGCs in 2012, below are the rates of adoption with respect to several key items of EGC relief:

- Confidential submission of Form S-1—67%

- Two years of audited financial statements—27%

- Two years of selected financial data—13% (27% with three or four)

- Deferred application of new or revised accounting standards—7%

- Omission of CD&A—73% (but 13% provided some narrative disclosure and 47% provided at least one optional compensation table)

"Testing-the-Waters" to Find IPO Investors

Companies contemplating an IPO often would like to get investor feedback—both in advance of the formal IPO process, to validate the company's decision to go public and begin to familiarize potential investors with the company, and after commencement of the formal IPO process, to educate target investors about the company and get some sense of the company's potential valuation. Although not commonplace, this feedback historically was sought through "non-deal" road shows held at least 30 days prior to the initial Form S-1 filing (in reliance on the Rule 163A safe harbour from quiet-period violations) and preliminary road shows conducted after the initial Form S-1 filing. Before the enactment of the JOBS Act, there was no clear legal basis for other forms of IPO pre-marketing in the United States.

Impact of JOBS Act

In a substantial departure from decades of securities law, the JOBS Act permits "emerging growth companies" (EGCs) and their authorized representatives to engage in oral or written "test-the-waters" communications with eligible institutional investors to determine their investment interest in a contemplated IPO, either prior to or following the filing of the Form S-1. By doing so, the JOBS Act has explicitly sanctioned, and established boundaries for, some types of pre-marketing activities by EGCs.

Potential investors eligible for "test-the- waters" communications consist of "qualified institutional buyers" (as defined in Rule 144A) and institutions that are "accredited investors" (as defined in Regulation D). The JOBS Act does not specify the manner in which EGCs should verify that potential investors are eligible to receive "test-the-waters" communications.

"Test-the-waters" communications can be brief and casual (such as a single conversation), or extensive and formal (such as a series of preliminary road show presentations). These communications can be used proactively to premarket an offering, or as a defensive measure to exempt a communication that would otherwise constitute an unlawful offer of securities.

Communications Procedures and Cautions

Before engaging in "test-the-waters" communications on behalf of an EGC, underwriters generally will require written authorization from the EGC. The EGC and underwriters should also agree in advance on the form and content of any materials that will be used in "test-the-waters" communications. Questionnaires or certifications can be used to confirm that all recipients of "test-the-waters" communications qualify as eligible institutional investors, although as a practical matter underwriters ordinarily know whether the investors to be approached are qualified.

An EGC should exercise caution with respect to "test-the-waters" communications. Under the underwriting agreement and federal securities laws, the EGC will face potential liability for these communications. The EGC should also assume that the SEC staff, as part of its review of the Form S-1, will request copies of any written "test-the-waters" communications and copies of any presentation slides used in conjunction with "test-the-waters" communications (even if copies are not provided to potential investors), and may raise questions if those materials are inconsistent with the disclosure in the Form S-1.

Market Practices

Market practices with respect to "test-the-waters" communications are still developing. A variety of informal "tes the-waters" communications are no doubt occurring, but to date the availability of the exemption does not appear to be significantly expanding the frequency with which EGCs and their underwriters are systematically approaching potential investors in advance of the formal road show, beyond situations in which preliminary road shows historically have been employed. "Test-the-waters" communications are most likely to be used to help gauge investor interest in companies with new or novel businesses or technologies, although as a practical matter it is difficult to have meaningful "price discovery" without the time pressure and competition of the formal road show. For obvious reasons, once the underwriters are selected, an EGC should not authorize anyone other than its underwriters to engage in "test-the- waters" communications (and the underwriting agreement will contain a representation to that effect).

As with other parts of the JOBS Act, the full potential of "test-the-waters" communications to improve access to the capital markets has not yet been realized. It remains to be seen whether underwriters will become more willing to hold "test-the-waters" meetings with potential IPO investors, and the extent to which institutional investors will be willing to take these meetings in advance of the formal road show.

Guidelines for "Test-the-Waters" Communications

Once selected, the lead underwriter is likely to have detailed procedures for "test-the-waters" communications. Typical procedures for these communications may be summarized as follows:

- Communications may only be with "qualified institutional buyers" and/or institutions that are "accredited investors."

- No written materials or handouts should be used (including "leave-behinds").

- Presentation materials should not be emailed or viewable except in person.

- The presentation and answers to anticipated questions should be scripted.

- Content must be factual, balanced and not misleading.

- Historical financial information is permitted, but projections are not.

- General valuation concepts may be discussed, but binding indications of interest may not be solicited.

- No media members may attend investor meetings, and no broadcasts or recordings may be made.

- Presentation materials and scripts should be reviewed in advance by counsel.

We're Going Public—What Will Be Disclosed About Me?

The good news is your company is going public. The bad news is your company has to open the kimono and publicly disclose a wealth of information about its business, finances, management and ownership. Set forth below is a thumbnail sketch of the disclosure requirements applicable to directors, officers, 5% stockholders and selling stockholders.

Timing of IPO Disclosures

- The vast majority of IPO companies can qualify as "emerging growth companies" (EGCs) under the JOBS Act. An EGC is allowed to submit a Form S-1 registration statement to the SEC for confidential review instead of filing it publicly. If electing confidential submission, the EGC must publicly file the Form S-1 on the SEC's EDGAR system at least 21 days before beginning the road show.

- Companies that do not qualify as EGCs must publicly file the Form S-1 and all amendments from the outset—hastening public disclosure of all information contained in the Form S-1.

Compensation

- For each of the company's named executive officers (NEOs), the FormS-1 must include information about salaries, bonuses, other incentivecompensation, perquisites, the amountand value of equity awards, the valuereceived upon exercise or vesting ofequity awards, potential payments uponemployment termination or a changein control of the company, and theterms of any employment agreements.

- Any management contract or any compensatory plan, contract or arrangement—broadly defined—in which any director or NEO participates is deemed a material contract and must be filed with the SEC. Any other management contract or compensatory plan, contract or arrangement in which any other executive officer participates is also considered a material contract, unless it is immaterial in amount or significance. This requirement applies to both written and unwritten contracts and arrangements; if not set forth in a formal document, a written description is required.

- A company's NEOs consist of anyone who served as the CEO or CFO during the previous fiscal year, regardless of compensation, and the other three highest-paid executive officers who were serving as executive officers at the end of the previous fiscal year (plus up to two additional individuals who served as executive officers during the year and for whom disclosure would have been required but for the fact that they were not serving as executive officers at the end of the previous fiscal year).

- EGCs are only required to have three NEOs (including the CEO), plus up to two additional individuals who served as executive officers during the year and for whom disclosure would have been required but for the fact that they were not serving as executive officers at the end of the last fiscal year.

- Compensation disclosures are for the fiscal year preceding the initial Form S-1 filing (or the initial submission of a draft Form S-1 for confidential SEC review, if applicable) plus subsequently completed fiscal years prior to effectiveness of the Form S-1.

- The Form S-1 must disclose director compensation (including consulting arrangements).

Stock Ownership

- The Form S-1 must disclose the beneficial stock ownership of each director, NEO, 5% stockholder and selling stockholder. A person is considered to have beneficial ownership of all company securities over which the person has or shares voting or investment power (or has the right to acquire voting or investment power within 60 days).

- Post-IPO, each director, officer and 10% stockholder must report stock ownershipas of the IPO and all changes in stockownership under Section 16 by filingForms 3, 4 and 5 with the SEC. For thispurpose, reported ownership is basedon "pecuniary interest," defined as theopportunity, directly or indirectly,to profit or share in any profit derivedfrom a transaction in the securities.

- Post-IPO, each 5% stockholder must file separate beneficial stockownership reports with the SECon a Schedule 13D or 13G.

Related Person Transactions

- The Form S-1 must disclose all transactions in which the company was a participant, since the beginning of the company's third preceding full fiscal year, that involved an amount in excess of $120,000 and in which any director or executive officer (or any immediate family member of the foregoing) had or will have a direct or indirect material interest.

- The Form S-1 must also disclose all transactions in which the company was a participant, since the beginning of the company's third preceding full fiscal year, that occurred while a stockholder was a 5% stockholder and involved an amount in excess of $120,000, if the 5% stockholder (or any immediate family member of the 5% stockholder) had or will have a direct or indirect material interest in the transaction.

Selling Stockholders

- The Form S-1 must disclose the name and beneficial stock ownership of each selling stockholder, state the number of shares to be sold by each selling stockholder, and indicate the nature of any position, office or other material relationship that any selling stockholder has had with the company within the past three years.

- An exception permits the company to make selling stockholder disclosures on an unnamed group basis if the aggregate holding of the group is less than 1% of the company's outstanding shares prior to the IPO.

Additional Requirements

- The Form S-1 must include specified biographical and background information for each director and executive officer.

- The Form S-1 must disclose specified bankruptcy, criminal, injunction, securities violation and stock exchange matters that occurred during the past 10 years and that are material to an evaluation of the ability or integrity of any director or executive officer.

Scheduling the First Annual Meeting of Stockholders

Now that you are a public company, it's time to think about the event where disclosure, corporate governance, investor relations and proxy voting advisory services (such as ISS) all intersect: the annual meeting of stockholders.

SEC rules do not require public companies to hold annual meetings of stockholders, but stock exchange rules do. Nasdaq requires a listed company to hold its first annual meeting within one year after its first fiscal year-end following an IPO. The NYSE requires a listed company to hold an annual meeting "during each fiscal year" and has informally indicated that a company's first annual meeting must be held no later than the second full fiscal year following its IPO (in practice, post-IPO companies listed on the NYSE rarely, if ever, wait this long).

Although annual meetings of stockholders generally are held approximately five months after fiscal year-end, public companies have some flexibility in picking the specific meeting date. In scheduling its first annual meeting of stockholders, a newly public company should consider the following factors:

- State Law Notice Requirements: The meeting notice (typically mailed together with the proxy statement, proxy card and the annual report to stockholders) needs to be provided within the time period prescribed by applicable state corporate law. The law of Delaware—the state of incorporation of a majority of all public companies—requires that stockholders be notified not less than 10 nor more than 60 days before the date of the meeting. Similarly, Delaware law provides that the record date for determining the stockholders entitled to notice of the meeting cannot be less than 10 nor more than 60 days before the date of the meeting.

- Distribution to Beneficial Holders: Apart from the minimum permitted notice period, ample time should be allotted for the mailing to reach all beneficial holders, including those whose shares are held in street name, and for votes to come in. The NYSE recommends that proxy materials be provided to nominee holders at least 30 days prior to the annual meeting. More time than historically necessary may be required because rule changes and the Dodd-Frank Act have eliminated discretionary broker voting of shares held in street name on nearly all matters, including uncontested director elections. Unless closely held, most companies distribute proxy materials at least 40 days before the annual meeting. Even if less time is needed to achieve a quorum and favorable stockholder votes at the meeting, notice of less than 30 days may adversely affect investor relations.

- E-Proxy Rules: If the company elects the "notice and access" option under the e-proxy rules, the company must provide the required notice to stockholders and post the proxy materials on its website at least 40 days prior to the meeting date. Street name intermediaries typically require another 5-10 business days of lead time from companies using the notice and access option.

- Bank and Broker-Dealer Inquiries: At least 20 business days prior to the record date, the transfer agent or proxy soliciting firm must inquire from all banks and broker-dealers holding the company's shares in street name as to how many sets of proxy materials will be required for distribution to beneficial holders.

- Filing of Preliminary Proxy Materials: Preliminary proxy materials (if required to be filed, such as for proposed business combinations and corporate charter amendments, or if seeking stockholder approval of any matters at a special meeting) must be filed with the SEC at least 10 days prior to the date on which definitive proxy materials are mailed to stockholders. The company should plan for the possibility that the mailing will be delayed in the event the SEC reviews the preliminary proxy material, or file it more than 10 days before the target mailing date.

- Stock Exchange Notice: Formal notice of the meeting date and the record date must be provided to the NYSE at least 10 days before the record date. Nasdaq does not require formal notice of the meeting or record date.

- Incorporation of Proxy Information into Form 10-K: A company can elect(and most do) to include in its proxystatement rather than in its Form 10-Kthe "Part III" information requiredunder the Form 10-K rules (specifiedinformation about directors, directorindependence, executive officers,executive compensation, corporategovernance, principal stockholders,related person transactions, and auditfees and services). In this event, thecompany's proxy materials must be filedwith the SEC within 120 days after the company's fiscal year-end. If the companyomits the Part III information from itsForm 10-K (which is due before the proxystatement is ordinarily completed) onthe assumption that the information willbe included in the proxy statement, andthe proxy statement is not filed within120 days after the company's fiscalyear-end, the company must amend theForm 10-K to add this information notlater than the 120th day after year-end.

- Annual Report to Stockholders: The proxy materials need to be accompanied (or preceded) by the annual report to stockholders, so time for its preparation must be built into the timeline— generally not a gating factor if the annual report consists solely of the Form 10-K plus a cover letter.

- Section 211 of Delaware Law: For a Delaware corporation, Section 211 of the Delaware General Corporation Law permits any stockholder of the company to request the Court of Chancery to order the company to hold an annual meeting if, among other circumstances, an annual meeting is not held for a period of 13 months. Absent special circumstances, such as litigation, it is unlikely that a stockholder or director will seek a Chancery Court order under Section 211.

- Director Attendance: The proxy statement must disclose the company's policy on director attendance at annual meetings and state the number of directors who attended the prior year's annual meeting. To make attendance at the annual meeting more convenient for directors—and help avoid embarrassing disclosure of poor attendance—many companies schedule the annual meeting to coincide with a regularly scheduled board meeting.

Form 10 IPOs—An Alternative Path to the Public Market

A new kind of IPO structure—called a "Form 10 IPO," can provide an alternative path to capital and public trading for smaller companies without significant revenue in high-risk industries, such as life sciences. Although not an IPO in the usual sense, a Form 10 IPO may be the most practical route to going public for some companies.

The traditional IPO route can be difficult. Given the length of time it takes to complete the overall IPO process, there is significant risk that market conditions will change between the time a company begins the process and the time it is ready to market the offering to investors. In addition, it can be challenging for companies with limited operating histories to gauge their valuations, even as late in the process as during the road show, causing some companies to price their IPOs well below the estimated range. In some instances, disappointing valuations have led companies to determine, either on the night of pricing or in the days or weeks leading up to pricing, not to move forward with their IPOs, despite having already invested significant time and expense in the process.

In response to these factors, the Form 10 IPO has emerged as an alternative to a conventional IPO. Previously, various forms of reverse-merger transactions had been the primary means for life sciences companies to go public if they could not complete a traditional IPO. Following the adoption of tightened stock exchange listing standards for reverse merger companies, the Form 10 IPO has become a more desirable alternative.

What is a Form 10 IPO?

In a Form 10 IPO, a private company sells securities in a private placement under Regulation D and, in connection with the private placement, agrees to file a Form 10 registration statement to become a reporting company under the Exchange Act, and to file a Form S-1 registration statement registering for resale the shares sold in the private placement. Typically, a Form 10 IPO company will arrange to have its stock quoted on an over-the-counter market and later seek to have its shares listed on a national securities exchange once it satisfies the applicable listing standards.

Advantages and Disadvantages

The principal advantage of a Form 10 IPO is that it can provide a company with significant capital more quickly than a conventional IPO. The following aspects of the Form 10 IPO process contribute to its advantages:

- The price at which the company raises capital is negotiated up front with the investors in the private placement.

- The SEC review process does not occur until after the sale of the securities.

- Institutional investors that ordinarily invest only in public companies may be willing to invest in a Form 10 IPO private placement.

- Much of the time, cost and expense associated with public company preparations can be deferred until after the company has received the capital. While these advantages may be very meaningful for some companies, there are also several disadvantages to a Form 10 IPO, including the following:

- It may be difficult for a smaller company to comply with its public reporting obligations under the Exchange Act, which become applicable as soon as the Form 10 becomes effective.

- The company may encounter difficulty in satisfying the public float and round-lot stockholder requirements for stock exchange listing.

- The elapsed time from the sale of the securities to trading on a stock exchange—the ultimate goal in a Form 10 IPO—may be no shorter than in a traditional IPO.

- If the company's stock trades below $5.00 per share and is not listed on a national securities exchange, the company will be subject to the SEC's "penny stock" rules, which could make it more difficult for broker-dealers to execute trades in the stock.

- The aggregate legal and accounting expenses incurred in connection with a Form 10 IPO will likely be as much, if not more, than those associated with a traditional IPO.

- The placement agent's fees may be based on a higher percentage of the financing proceeds than the percentage underwriting discount in a conventional IPO, and the company may also need to issue warrants to the placement agent as additional compensation.

- Research coverage may be more difficult, and perhaps impossible, to obtain.

- Major investment banks may be less likely to underwrite the company's follow-on offerings because they did not have the opportunity to become familiar with the company during a conventional IPO process.

- The intangible benefits of enhanced prestige and credibility provided by a conventional IPO will be delayed, or not present at all.

- Because the JOBS Act does not permit Form 10 registration statements to be submitted for confidential SEC review, an emerging growth company's plans to pursue a Form 10 IPO will become public knowledge as soon as it files the Form 10.

Offering Process

The Form 10 IPO offering process has multiple steps:

- Pre-Financing Preparation: The Form 10 IPO process typically begins with the company's engagement of an investment bank. Once the investment bank is selected and engaged, the company and the bank will determine the appropriate path and timeline for the company's process. The investment bank will also act as placement agent in connection with the initial private placement.

- The Private Placement: The company and placement agent will work together to identify investors and negotiate the private placement, which is completed pursuant to the exemption from registration provided by Regulation D. The securities sold in the financing can consist of shares of preferred or common stock, and will be sold pursuant to a stock purchase agreement. In addition to normal private placement terms, the stock purchase agreement will include the company's commitment, following the financing, to file a Form 10 registration statement to become a reporting company and to arrange to have its shares traded on an over-the-counter market and/or listed on a stock exchange.

- Public Company Preparation: The company will become subject to the Exchange Act reporting requirements on the day the Form 10 becomes effective. As a reporting company, the company will be required to file Form 8-Ks, 10-Ks and 10-Qs. In addition, insiders and 10% stockholders will be required to file Form 3s and 4s, and 5% stockholders will be required to file Schedule 13Ds or 13Gs. Therefore, the company should begin its public company preparations, which are similar to those of a private company pursuing a traditional IPO, at the time of the private placement.

- Governance Preparation for Stock Exchange Listing: Since the eventual goal of theForm 10 IPO process is for the company'sstock to be listed on a national securitiesexchange, the company must determineearly in the process how it plans tosatisfy the applicable listing standards.Particular consideration should be givento the non-affiliate float and round-lotstockholder requirements. In addition,because the phase-in rules applicable tocompanies listing on a stock exchange inconnection with an IPO are not availableto a company going public throughthe Form 10 IPO process, the companymust be prepared to be fully compliantwith the director independence andcommittee composition requirementsat the time it seeks listing.

- Form 10 Registration Statement: The Form 10 registration statement contains information similar to that required in a Form S-1 registration statement, with the exception of information specific to the securities offering. The SEC review process is also similar to the Form S-1 review process—the SEC will review and provide comments on the Form 10 registration statement and the company will respond to the SEC's comments through response letters and Form 10 amendments. However, unlike a Form S-1, the Form 10 will automatically become effective 60 days after filing, unless withdrawn by the company. In the event significant issues remain unresolved as the date of effectiveness approaches, the SEC may request that the company withdraw the registration statement prior to effectiveness, or the company may elect on its own to do so. If the company does withdraw the Form 10, whether at the request of the SEC or on its own, a new 60-day clock will begin when the Form 10 is refiled.

- PIPE Financing: To comply with the securities exchange listing standards, which require that a company have a minimum number of round-lot stockholders and a minimum amount of non-affiliate public float, a Form 10 IPO company may determine to conduct a PIPE financing after the Form 10 becomes effective. A primary goal for the PIPE financing will be to increase the company's non-affiliate stockholder base.

- Resale Form S-1: After the Form 10 has cleared SEC comments and gone effective, the company will draft and file with the SEC a resale Form S-1, registering for resale the shares sold in the private placement and the PIPE financing, if any. The purpose of the resale Form S-1 is to provide liquidity to the investors and to facilitate trading in the stock.

- Over-the-Counter Trading: A Form 10 IPO company usually will be unable to satisfy the applicable standards for listing its stock on a securities exchange immediately following effectiveness of the Form 10. Instead, the company will likely arrange through a broker-dealer, usually the investment bank assisting the company with its Form 10 IPO, to have the company's stock quoted on an over-the-counter system. Over-the-counter trading provides liquidity for the company's investors, as well as an opportunity for the company to increase its non-affiliate stockholder base and otherwise progress towards satisfying the stock exchange listing standards.

- Stock Exchange Listing: Once the company satisfies the applicable listing standards, including the director independence and committee composition requirements for which there is no grace period in the context of a Form 10 IPO, the company may list its shares on a stock exchange.

Outlook

For companies that anticipate having a difficult time successfully marketing, pricing and completing a traditional IPO, a Form 10 IPO may be appealing. However, a Form 10 IPO is not feasible for all companies and, even for those companies that are in a position to take advantage of the benefits, there is the fundamental trade-off of time to capital versus time to market, liquidity and access to additional capital.

To date, few companies have completed Form 10 IPOs, and the extent to which this market will broaden remains to be seen. One notable Form 10 IPO success story is that of OvaScience, a life sciences company developing proprietary products to improve the treatment of female infertility. Shortly after formation in April 2011, OvaScience raised $6.2 million in venture capital financing. In March 2012, OvaScience raised an additional $37.2 million through a placement agent. OvaScience filed a Form 10 registration statement in April 2012, becoming a public reporting company in June 2012, and a Form S-1 resale registration statement in August 2012, and its common stock began to trade on the OTC Bulletin Board in November 2012. OvaScience increased its stockholder base through a $4.9 million PIPE financing in August 2012 and raised $35.0 million in another PIPE financing in March 2013. In April 2013, OvaScience's common stock was listed on Nasdaq.

Interest in Form 10 IPOs may grow as the process becomes better known among IPO candidates and potential Form 10 IPO investors. Moreover, the JOBS Act's mandate to eliminate the prohibition on general solicitation and general advertising in private placements conducted pursuant to Rule 506 under Regulation D, once implemented, may help companies identify investors for private placements and PIPE financings in conjunction with a Form 10 IPO. In any event, a Form 10 IPO should remain a possibility for some private companies that seek public investor capital but are looking to avoid the market fluctuation and pricing risks associated with raising money through a traditional IPO.

Please click here to view original article (PDF)

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.